The Elephant Needs the Room

Photos by Forrest Anderson

Every so often, I like to check in on the elephants. Why? Because in the critical area of conservation, they’re literally the elephant in the room. The topic of saving the elephants is a big subject, so bear with me.

In the earth’s crisis over preservation of species, the tug o’ war between the elephant’s survival and the use of its teeth for luxury trinkets is an especially horrifying example of irrational destruction.

Elephants use their long teeth called tusks to defend themselves, dig, eat, push through dense forests, forage and strip bark from trees. The two-thirds of an elephant’s tusk that protrudes from its head is called ivory. On the black market, ivory tusks can start at $1,500 each.

This hard substance called ivory has been carved into beautiful, intricate works of art since prehistoric times. Its appeal is that it is possible to carve into it amazingly fine detail. Extremely durable, ivory carvings from many cultures and eras have survived for millennia, even from civilizations where there is little extant stone sculpture. The luxury history of the world has been carved in ivory. Many types of animal teeth have been used but the most common are elephant tusks, which are relatively soft and large enough to create substantial works of art.

Once carved into piano keys, boxes, pipes, game pieces and a wide variety of other items, ivory today has little practical use. For most purposes, it has long been supplanted by plastics and resin products that function just as well or better. Today's market for ivory rests on its historic reputation as a luxury item for the elite. The supreme irony of the elephant’s plight is that the demand for its tusks has burgeoned even as it is possible to substitute them for less destructive products.

This growing demand has become the elephant’s 21st century woe. In the 19th century, there were an estimated 5 million elephants in Africa and Asia. By 1942, that number was down to 1.5 million. By the 1980s, it had dropped to 600,000. Today, there are an estimated 450,000 African elephants or maybe a bit more and between 35,000-40,000 wild Asian elephants. The number of wild elephants declined by almost a third in the last decade. About 20,000 elephants a year are slaughtered for ivory, by far the prime factor in the decline of the elephant population. One elephant is killed every 26 minutes.

These highly intelligent, compassionate herd animals will disappear from many places in Africa in the next few decades unless poaching of them stops.

The African Elephant Status Report 2016 by the International Union for Conservation of Nature said that for the first time in a quarter century, the African elephant population had declined all across Africa. The subspecies of forest elephants are especially vulnerable because of poaching and reduction of habitat combined with a low birth rate, but the more resilient savannah elephants also have lost a third of their population in the past seven years.

In the past decade, the illegal ivory trade has reached levels not seen since the 1970s even though the sale of ivory is banned worldwide. Illegal poaching of elephants supplies ivory to a thriving black market in China, Japan, and some other Asian nations and to American tourists who smuggle ivory into the United States.

The African elephant lives in 37 countries across west, central, eastern, and southern Africa, more than 70 percent of them in southern Africa. The worst poaching is in eastern Africa where roughly half of the elephants have been killed in the past decade. Herds in Tanzania have been the hardest hit. Central Africa and west Africa have also had significant losses, while herds in Namibia, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Uganda, Kenya, and Rwanda are stable or increasing. Even if poaching were to end, it would take more than a century to recover the past decade’s losses.

Current strategies to save the elephants include protecting them from poaching, gathering data on elephant populations, intercepting ivory trafficking, legal penalties and bans on poaching and ivory trading, and public education in countries where there is a demand for ivory. However, as with many other environmental efforts, trends still point to too little too late.

A Brief History of Ivory

Ivory carving is part of the history and culture of many cultures, most notably Egyptian, Greek, Roman, European medieval, Byzantium, Chinese, Japanese, Islamic and African. The oldest likeness of a human face, the 25,000-year-old Venus of Brassempouy, was carved from mammoth ivory. While walrus and mammoth tusks also are used for ivory carving, the major source of ivory has been the African and Asian elephants. Elephants became extinct in ancient times in China partly because they were killed for their ivory. The demand for ivory wiped out the elephant population in northern Africa 1,000 years ago.

Ivory was used in antiquity for parts of carvings that represent human skin. The statue of Athena at the center of the Parthenon was made with this technique. Ivory’s smooth white beauty made it the material of choice for religious statues in a wide variety of cultures. Today, it retains a religious connection, especially with the Virgin Mary, in some cultures that makes it difficult to convince devotees to abandon the carving and purchase of ivory figures.

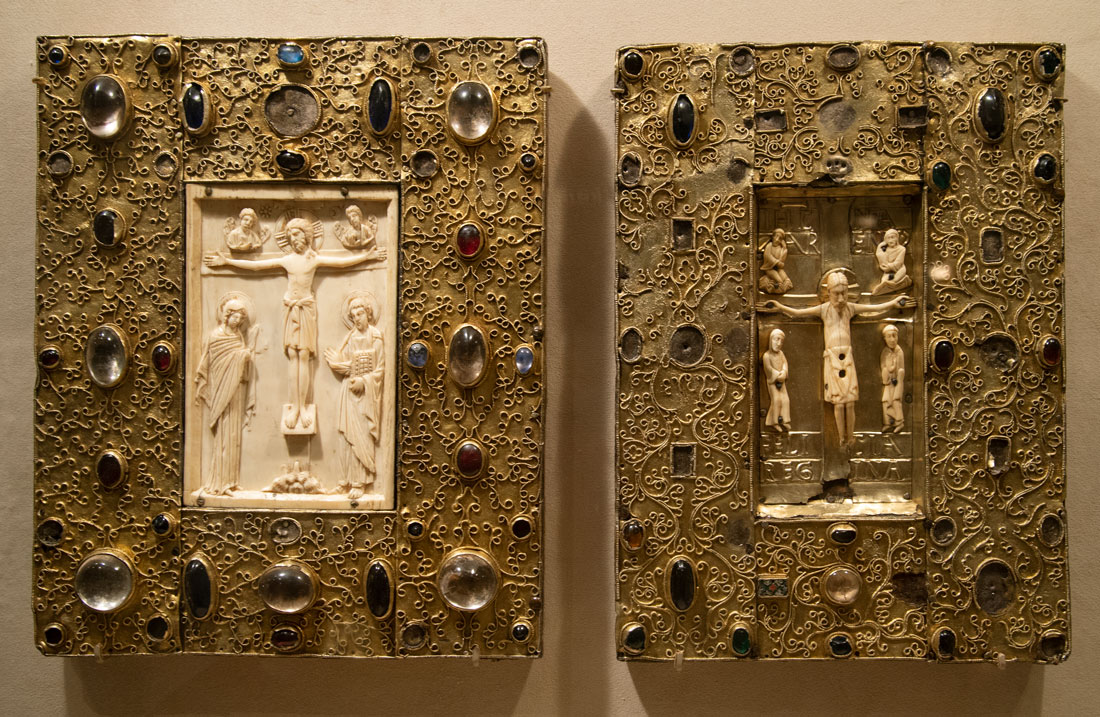

The Roman consuls gave carved ivory panels with their images carved on them as presents. Christians later adapted these diptychs and triptychs with carved images of Christ, Mary and saints that became objects of prayer. Ivory panels carved with similar images and joined with jewels covered the most valuable illuminated manuscripts. Some panels were fashioned into boxes in which saints’ relics were stored. Many of these panels survived because unlike jewels, they couldn’t be recycled and, unlike wood, they were durable. They are today an important record of medieval art and history.

This ivory triptych depicts the crucification of Christ, the Virgin Mary, angels and saints. It is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Ivory was also carved in the round into statues, chess pieces, olifants (hunting horns made from the tips of tusks) and often gilded or colored.

A Byzantine ivory panel at the Louvre Museum in Paris, France.

A jewelled book cover with an ivory panel at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

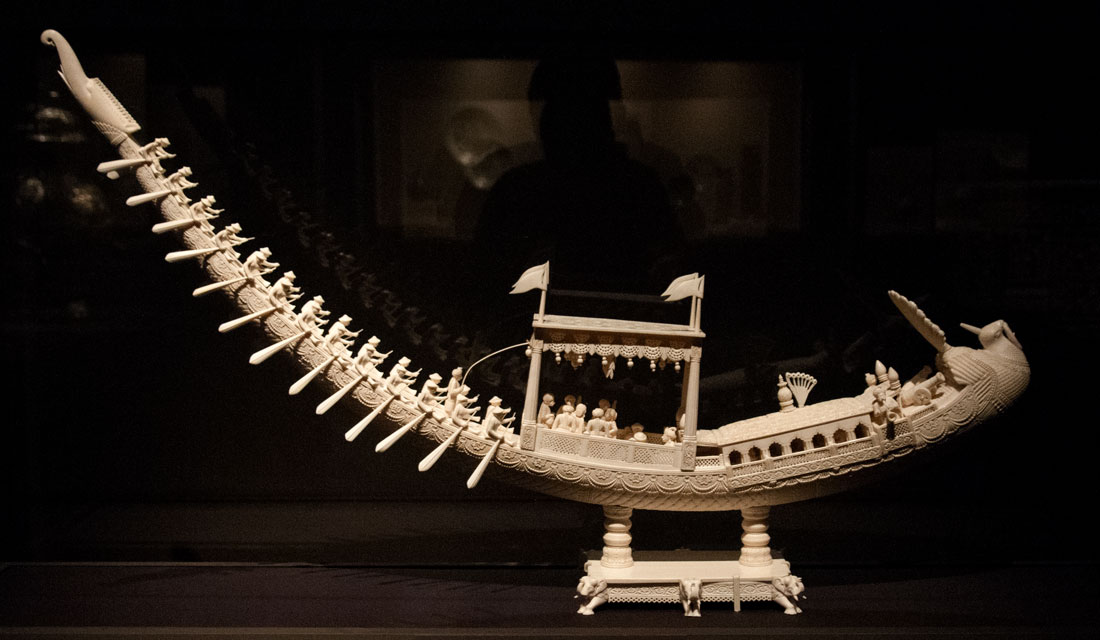

Paris became an important center of ivory carving in the Middle Ages, beginning with religious-themed products for the clergy and expanding into secular or religious ones for the elite. Combs, fans, cutlery handles, mirror-cases, game pieces, boxes, model ships, balls for billiards and other table games were produced.

From 750-1258, Islamic carvers applied intricate Islamic patterns to boxes, panels and other items.

Murshidabad, India, was a famous ivory carving center as were several other Indian cities.

A late 19th century Indian ivory carving of a royal peacock boat, now in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Ivory was a valued product largely confined to elites. In Africa’s lower Congo, it was controlled by rulers who commissioned sculptors to produce fine ivory sculptures for their own and court use. As the transatlantic trade grew from the 16th to 19th centuries, that changed. Kongo ivory carvers began to produce works for Europeans and other foreign markets, so the demand for ivory spread. The trade burgeoned into a huge international one.

From the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) on, the Chinese used ivory for small statues of gods and other items. It was used during the subsequent Qing dynasty (1644-1912) for brush-holders, boxes and handles. Since the 17th century, the Japanese had used ivory to carve small items such as the netsuke they wore on their sashes and inlay on swords. By the 18th century, China was producing ivory carving for export to Europe. The Japanese followed in the late19th century with exquisite statuettes and puzzle balls.

An ivory statue of a Chinese scholar, now in the San Francisco Museum of Art.

During the 19th century, ivory was ubiquitous. Its use spread along with the use of tobacco and opium for pipes and other smoking paraphernalia. Walking stick heads, boxes, jewelry, snuff bottles, piano keys, violin bows, game pieces, and a wide variety of other ivory objects were made for the middle classes. Hundreds of tons of ivory were taken out of Africa during the continent’s European colonization, often transported by slaves.

19th century ivory items in an antique shop in Paris, France.

Ivory took on deep religious meaning because it was carved into Christian, Islamic, Buddhist and other religious forms that permeated the cultures of lands where those religions spread. Ivory crucifixes, statues of the Virgin Mary and other highly prized religious items graced church altars, homes and shrines worldwide.

In the 1970s, newly prosperous Japan began to buy ivory in large quantities to carve into hankos, or name seals, which had previously been made from wood with an ivory tip but came to be mass-produced entirely from ivory. Japan began to import 40 percent of the ivory on the market to carve into jewelry and souvenirs. At the same time, Hong Kong’s ivory carving industry burgeoned and took up another 40 percent of the ivory market, with most of its products going to Europe and North America. The elephant population predictably plummeted. About 75,000 elephants were killed for their tusks annually, some 80 percent of them illegally.

Banning Ivory

The slaughter spawned a conservationist backlash in the 1980s. Ending the ivory trade, however, has proved to be an immensely complicated, difficult task.

Elephant poaching had become deeply embedded in the culture and economies of a number of areas in Africa and had contributed to a breakdown in law and order in areas where it occurred. It also had become a valuable currency used by competing armies to buy weapons.

Poaching is the primary threat to African elephants. Other lesser causes are fencing that has disrupted their migratory patterns and caused herds to separate and become isolated, climate change and conflicts with humans.

In 1975, a multilateral treaty, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora or CITES, went into force. CITES in the 1980s instituted a system of paper permits, registration of large ivory stockpiles and monitoring of legal ivory movements. However, the system had some major flaws. Large poaching syndicates got stacks of permits while also illegally smuggling new ivory. If stopped by customs, they would produce a paper permit. The system became a cover for their activities. It also increased the value of ivory on the international market, so smugglers were actually rewarded by it. Investigations by independent watchdog groups found that large amounts of ivory continued to be smuggled out of countries such as Tanzania which had banned the ivory trade because there was a thriving demand for ivory in other countries. CITES officials struggled to enforce international restrictions on elephant poaching, frequently encountering violent bands of poachers willing to fight pitched battles in which people on both sides were killed.

Tanzania proposed that CITES designate Appendix One listing for the African elephant (effectively a ban on international trade), which South Africa and Zimbabwe opposed. Both countries claimed that they were managing their elephant populations well and wanted revenue from ivory to fund their conservation efforts. The World Wildlife Fund had strong ties to both countries and tried to appease them while opposing the ivory trade. Finally, with Somalia’s support, CITES adopted the Appendix One designation with its ban on elephant ivory trade. The international ivory trade was banned in January 1990.

The result was that the poaching epidemic subsided somewhat, ivory prices plummeted and ivory markets, most of them in Europe and the United States, closed. The publicity over the decision created a widely accepted perception that the ivory trade was harmful and illegal.

However, a group of southern African countries – South Africa, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia and Swaziland as well as Hong Kong and Japanese ivory traders - continued to work against Appendix One. Supporters of the ban pointed out that although South Africa’s elephants were well managed, South Africa trained, supplied and equipped the rebel Mozambique army RENAMO which was heavily implicated in poaching. They also noted that Zimbabwe, although it had model sustainable wildlife policies, was using revenues from ivory trading for general government expenses rather than conservation. Zimbabwe also was accused of double counting elephants crossing its border with Botswana and its army was involved in poaching in Mozambique. Some who claimed that this was happening were killed. Zimbabwe’s former president Robert Mugabe, who led the efforts to push for the international ivory trade, was accused of trading tons of ivory to China for weapons. Nonetheless, CITES in 1997 agreed to change African elephants in Botswana, Namibia and Zimbabwe to Appendix Two, allowing international trade in elephant parts. These countries sold ivory to Japan as an experiment in 1997. Three years later, South Africa’s elephants also were changed to Appendix Two to allow South Africa to sell its ivory stockpile.

Prominent scientists take the position that the South African model, in which 90 percent of the elephants live within a fenced national park, is not typical since most African elephants live in poorly protected unfenced areas and need stronger legal protections.

CITES established two systems to inform member states on illegal killing of elephants and trade - Monitoring the Illegal Killing of Elephants (MIKE) and Elephant Trade Information System (ETIS). The systems collect information on poaching and seizures provided by member states.

In the 1990s, international ivory syndicates continued to operate, with suspected ivory shipments from Zambia collected in Malawi, shipped out of South Africa and ending up in China and Singapore. In 2002, six tons of illegal ivory were seized in Singapore. The case indicated that Hong Kong syndicates were at the center of the trade.

In 2002, 60 tons of ivory from South Africa, Botswana and Namibia were approved for sale. Japan was approved in 2006 as a destination for the ivory, even though 25 percent of the Japanese traders were not registered and registration was voluntary. China also sought approval as a destination country. Chinese ivory carvers in the 1990s mainly supplied carvings to shops in other Asian countries such as Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Malaysia and Indonesia, with few of their products sold on the Chinese domestic market. However, as China became more prosperous in the early 2000s, the domestic demand for ivory grew exponentially.

Ivory carving in a Beijing factory before China banned the ivory trade.

A woman carves a detail on ivory in a Chinese factory, again before China's ban on ivory carving.

Despite evidence that China wasn’t controlling its ivory stockpile, CITES approved China as an ivory destination on July 14, 2008. China was soon the world’s primary legal ivory market. China and Japan bought 108 tons of ivory in a one-off sale in November 2008 from Botswana, South Africa, Namibia and Zimbabwe. The idea behind the sale was to depress the global price of ivory and thus decrease poaching. The demand for ivory has indeed decreased since 2012, but primarily because of higher consumer awareness about the connection between ivory and endangering elephants.

At the same time, China has become heavily involved in African infrastructure projects and the purchase of African natural resources, alarming conservationists because the smuggling of ivory also has increased dramatically. Chinese nationals were caught smuggling ivory in many African countries at the same time as the Chinese domestic market for ivory grew and the price of ivory tripled from 2011-2015. The New York Times reported in 2012 a major increase in poaching of ivory, about 70 percent of which was going to China. In 2013, Chinese authorities seized 1,913 tusks in the Chinese city of Guangzhou.

Meanwhile, many African countries continued to push for a total ivory trade ban. In 2006, 19 African countries called for a total ban and 20 states with elephant range called in 2007 for a 20-year moratorium on the trade.

President Xi Jinping and then-U.S. President Barack Obama in 2015 agreed that their countries would end their legal ivory trade. The U.S. ban went into effect in June 2016. China banned all ivory trade and processing activities in China at the end of 2017. Independent surveys of licensed ivory shops in China indicate that they either closed or no longer sell ivory, but ivory has been found illegally for sale in other shops. The overall amount on sale has decreased, however.

Some Chinese artists have transitioned to carving mammoth tusks and ox bones.

Hong Kong’s thriving ivory market is regulated separately from mainland China's. Hong Kong has announced a five-year plan to phase out its elephant ivory trade by 2021. Currently stockpiled goods still can be sold legally in Hong Kong.

Experts say the key to making the ban successful is Chinese law enforcement and education. China in coordination with international wildlife conservation associations launched a public awareness campaign encouraging people to respect the ban. It’s too early to tell whether the ban has had an effect on poaching in Africa.

In 2017, an undercover operation by the London-based watchdog group Environmental Investigation Agency exposed an illegal trafficking syndicate in the town of Shuidong, China, which receives up to 80 percent of the illegal African ivory. EIA informed the Chinese police, who raided several places in the Shuidong area and arrested 12 people who were sentenced to jail. Two others who were outside China also returned voluntarily or were repatriated to China and arrested.

EIA said in its report that the Shuidong syndicate was supported by a network of corrupt rangers, customs officers, shipping agents, lawyers and others in Tanzania, Mozambique, South Korea and Hong Kong. When anti-poaching enforcement in Tanzania improved, the smugglers moved into neighboring Mozambique. Between 2009 and 2014, Tanzania lost 60 percent of its elephant population and Mozambique lost 53 percent.

Vietnam and Laos also have been criticized for ivory trafficking to meet the Chinese demand for ivory. Other centers of ivory trade have been the Philippines and Thailand.

EIA also reported after a two-year investigation that illegal ivory and other contraband wildlife parts were entering Vietnam in large amounts, accelerating the decline in all of the affected animals’ populations. The EIA said Vietnam was a primary hub for illegal ivory destined for China. However, arrests in Vietnam are few and sentences weak.

The Vietnamese, EIA reported, have developed sophisticated practices for concealing smuggling, including specialist air, land and sea transportation facilitated by corruption all along the transportation routes. Ivory is hidden in hollowed timber or wax encasings and smuggled out of Mozambique to Malaysia and then Laos, where it goes overland to Vietnam. Some of the ivory stays in Laos and is sold there to visiting Chinese tourists and locals.

Between January 2016 and November 2017, at least 22 shipments of ivory weighing nearly 19 tons and worth some $14 million were smuggled from Africa in this way.

The ivory was bought mainly by Chinese in the forms of jewelry or raw tusks. Nhi Khe, a village near the border with China, became an important ivory hub that one smuggler claimed sold more than 11 tons of ivory a month.

The demand for ivory in China has been fueled by increased prosperity and the historical connection of ivory with China’s past imperial glory and luxury, which many prosperous Chinese businessmen want to restore. Some of these buyers have not been dissuaded by the fact that the ivory trade will end if all elephants are killed. On the contrary, price increases have been driven up by the elephant’s threatened extinction as many buyers consider owning a rare item a mark of status.

In the U.S., the ivory trade was for many years allowed for ivory brought into the country legally before 1990, taken from elephants killed before 1976, and for antiques and trophies from legal sport hunting. In June 2016 the United States banned the buying and selling of almost all ivory, with exceptions for century-old antiques and a few other categories. Oregon, Washington, California, Hawaii, Nevada, New Jersey and New York also have banned the sale of products from some endangered animals,

Alaskan Native Americans are allowed to harvest walrus for subsistence and can sell the ivory to non-natives as long as they report it to a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service representative and it is tagged and fashioned into a handicraft. They also can sell ivory found within a quarter mile of the ocean if it is tagged and carved. Moscow is a major center for the trade in walrus ivory. Inuit traders also are challenging an international export ban on trading of narwal tusks, for which Denmark is the largest purchaser.

In 2018, a study by Avaaz sponsored by Oxford University indicated that legal antique ivory trading in the European Union was fueling elephant poaching because a loophole that allows for trading of antique ivory masks is enabling the sale of ivory from recently killed elephants.

On December 20, 2018, the United Kingdom passed one of the toughest bans yet on ivory trading within its territories, including elephant, hippopotamus, walrus and narwhal ivory. The ban goes into effect in late 2019. The act will ban all trade in items containing elephant ivory regardless of age within the United Kingdom as well as export from or import into the United Kingdom.

The law has a few exemptions such as antique items with less than 10 percent ivory, musical instruments such as pianos and violins with less than 20 percent ivory, portrait miniatures made on thin slivers of ivory and placed in lockets, sales to and between accredited museums and items of outstanding artistic, cultural or historic significance made before 1918. The act established tough fines and possible imprisonment for violation.

The act aims to reduce illegal killing of African elephants by at least a third by the end of 2020 and two-thirds by the end of 2024 by reducing demand. It sends a powerful message in a country that has been one of the largest markets for ivory. The 19 African countries that form the Elephant Protection Initiative see the law as a breakthrough in their struggle to save their elephants.

Public opinion in the UK was overwhelmingly in favor of the ban. Some British antique dealers are considering relocating their businesses to continental Europe or the Netherlands, as European Union dealers can trade in worked ivory dating from before 1947 because of an exemption in the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. It has become more difficult in recent years to sell ivory and its price has dropped. Other dealers are no longer buying and selling ivory items.

Mammoth Tusks

Some ivory traders have turned to mammoth tusks as an alternative to elephant ivory. The last mammoth died out 5,600 years ago, so using their tusks has the obvious advantage that they can no longer go extinct. Mammoth tusks were first traded in western Europe in 1611 with a piece from Siberia arriving in London. After Russia conquered Siberia in 1582, ivory was more readily available. The Siberian mammoth ivory trade grew from the mid-18th century on and an estimated 46,750 mammoths have been excavated since Siberia became part of Russia. In some cases, convicts serving time in Siberia were used to extract the mammoth tusks. Mammoth ivory was used in the early 19th century for piano keys, billiard balls and ornamental boxes.

Global warming has melted permafrost in northern Russia, where millions of wooly mammoths roamed during the last Ice Age, and exposed mammoth tusks. Once excavated, they are being sold to Hong Kong dealers. The Chinese ban on ivory trading has expaned the trade in mammoth ivory. It is unclear whether the mammoth trade is giving African elephants a reprieve, however, because some experts think it is continuing to shore up a demand for ivory that should disappear entirely and also to launder African ivory.

Hong Kong is the main center for mammoth ivory, and craft stores on Hollywood Road there display signs claiming their products are carved from mammoth ivory. Hong Kong in 2017 imported almost seven tons of the so-called ice ivory, according the Census and Statistics Department. This is down from 2014, during which 50 tons of ice ivory was imported into Hong Kong.

Mammoth tusk hunters break up the permafrost using water jets to free the tusks, although the use of water jets in excavations in illegal in Russia. Scientists worry about damage to ancient remains and archaeological sites because of the tusk harvesting. However, some Russian scientists say museums already have enough mammoth tusks to study. They collaborate with hunters because hunters bring them carcasses, bones and other finds that are interesting but have no market value.

Some carvers like mammoth tusks better than elephant ones, saying they are higher quality. High quality mammoth ivory costs significantly more than elephant ivory. Legal traders and carvers say that with severe penalties against the use of elephant tusks and with mammoth tusk dealers providing authenticity certificates after testing the age of materials, they prefer mammoth tusks.

Trophy Hunting of Elephants

On March 1, 2018, the Trump administration lifted an Obama-era ban on importing sport-hunted trophies of elephants from certain African countries. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service said that instead, it will consider importation permits "on a case-by-case basis."

The memo did not clarify the specific guidelines by which the permits would be judged. The change was a surprise because Trump had publicly expressed his opposition several times to ending the blanket ban. The D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals had ruled that the Obama administration had acted improperly in implementing the ban by not sufficiently observing the rules around creating a new regulation, such as inviting public comment. The reversal means that the remains of elephants legally hunted in Zimbabwe and Zambia can be legally imported into the US as trophies.

Hunting advocates argue that revenue from legal hunting in Zimbabwe and Zambia helps fund conservation efforts. But conservationists say the decision will undermine campaigns spearheaded by the United States to stop the ivory trade. More than a million people signed a petition against the change.

Britain is another country with a high number of trophy hunters that kill elephants.

The Campaign to Ban Trophy Hunting says 100,000 elephant tusks have been hacked off dead animals and brought home by hunters worldwide since the 1980s. There was a four-fold increase in the number of elephant trophies taken in 2015 compared with 1985 and the number of countries from which the hunters came doubled to almost 50 from fewer than 20. Trophy hunting has sparked large protests around the world.

CITES allows hunters permits to kill even protected animals facing extinction, which activists want stopped. They also want a ban on captive breeding of endangered animals to harvest their parts, as they say this fuels a demand for the parts.

Biologists say trophy hunting is particularly pernicious because it kills the highest quality animals with the strongest genes who are more likely to survive otherwise, reducing the entire specie’s chance of survival.

Asian Elephants

Nearly a third of the ones in India, Myanmar and Thailand live not in the wild but as working elephants in the timber or tourism industry. Captive elephants are vulnerable to decline. A study published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B indicates that young captive elephants have a higher risk of early death when separated from their mothers to start training. Elephants have strong family bonds and when they are separated from their mothers, they become stressed. Improving care of pregnant females also could improve the chances for survival of their young.

Working elephants in Thailand.

About 60 percent of the global population of the Asian elephant lives in India and Nepal, where they are faced with significant loss of habitat because of climate change and human development. They are likely to migrate toward higher elevations in the Himalayas as a result, but researchers anticipate that the effect on their population will be severe.

Technology in the Service of Elephant conservation

A bright spot in efforts to change the bleak outlook for elephants may be in the use of technology. Here are some developments that are under way:

Scientists at the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Forensics Laboratory in Ashland, Oregon, have been able to determine in some cases that ivory figures sold online were from endangered African elephants rather than extinct mammoths based on the placement and shape of tiny tubules in cross sections of the ivory. They have extracted DNA from the ivory and compared it to that of known elephant species to match it to the DNA of the endangered African bush elephant. This evidence then is used to prosecute people illegally engaging in the ivory trade.

Researchers have collected large databases of sound recordings from African forests, photos from camera traps and other media resources that they are attempting to combine with machine learning and artificial intelligence so that law enforement officers can have access to real-time information indicating poachers are in specific locations in elephants' habitats. The hope is that this technology can be in use within a decade or two.

On iNaturalist, one of the world’s largest biodiversity citizen science monitoring applications, anyone can post a photo of a plant or animal which experts then identify. The tool has led to discoveries of new species and significant range expansions for known ones. iNaturalist built a computer vision algorithm into the app that identifies a species’ genus with nearly 90% accuracy and presents users with five top species suggestions based on where and what time of day the photo was taken. When complete, the program will be able to instruct park managers about the optimal places to send anti-poaching patrols.

Drones initially were largely a failure in helping to find poachers, but are now less expensive and the data they collect may in the future be integrated into these advanced tools so footage from drones doesn’t have to be analyzed manually.

The results of these technologies may give patrols radical advantages. Satellites also may monitor boats so that they don’t stray into protected areas and so-called smart nature parks will use technology to send real-time alerts to rangers.

Skin Beads

Meanwhile, elephants are facing a new danger - the harvesting of their skins to make beads. Skin poaching could wipe out Myanmar’s wild elephants in less than 60 years. Researchers with the Conservation Ecology Center discovered the skin poaching when they placed GPS collars on 19 Asian elephants in Myanmar and a number of the collared animals were poached.

Elephant Family, a British conservation group, found online ads for beads made from Asian elephant skin and that illegal traders in China were the main customers for the skin. The inch-thick skin is cut into cubes, dried and turned into beads that are sold as prayer bracelets, necklaces and other collectibles. They look like a red stone because the skin layers contain blood. Chinese officials have denied the findings of the Elephant Family’s report.

This ivory rosary from Germany encouraged its users in Latin inscriptions carved on it to "Think of death" as they used it. If more people do that when seeing ivory, perhaps Africa's elephant herds can be spared. The rosary is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Related photos:

Check out these related items

California’s Sea Monsters

In fall and winter, tens of thousands of elephant seals make a migration to California's coastal rockeries to breed and give birth.

Feathers of a Bird

Of all creatures, only birds have feathers. These delicate, sophisticated, beautiful structures perfectly combine form and function.

Fire! Is this the new norm?

Are record wildfires the new norm in the West? As fires threaten homes and communities, here are answers to questions about them.

The River That Keeps on Giving

The mammoth Colorado River is the lifeblood of the southwest United States, supplying water and power for cities and agriculture.

Sustainable Bamboo

Eat it, build a home or furniture with it, use it in the kitchen, use it for plumbing, wear it, make fences or containers with it.

Lighthouse, Tide Pools and Seals

Yaquina Head, Ore., has one of the Pacific Coast’s premier tide pool observation sites, a lighthouse and seal and seabird colonies.