Mountain Men and the Fur Trade

Photos by Forrest Anderson

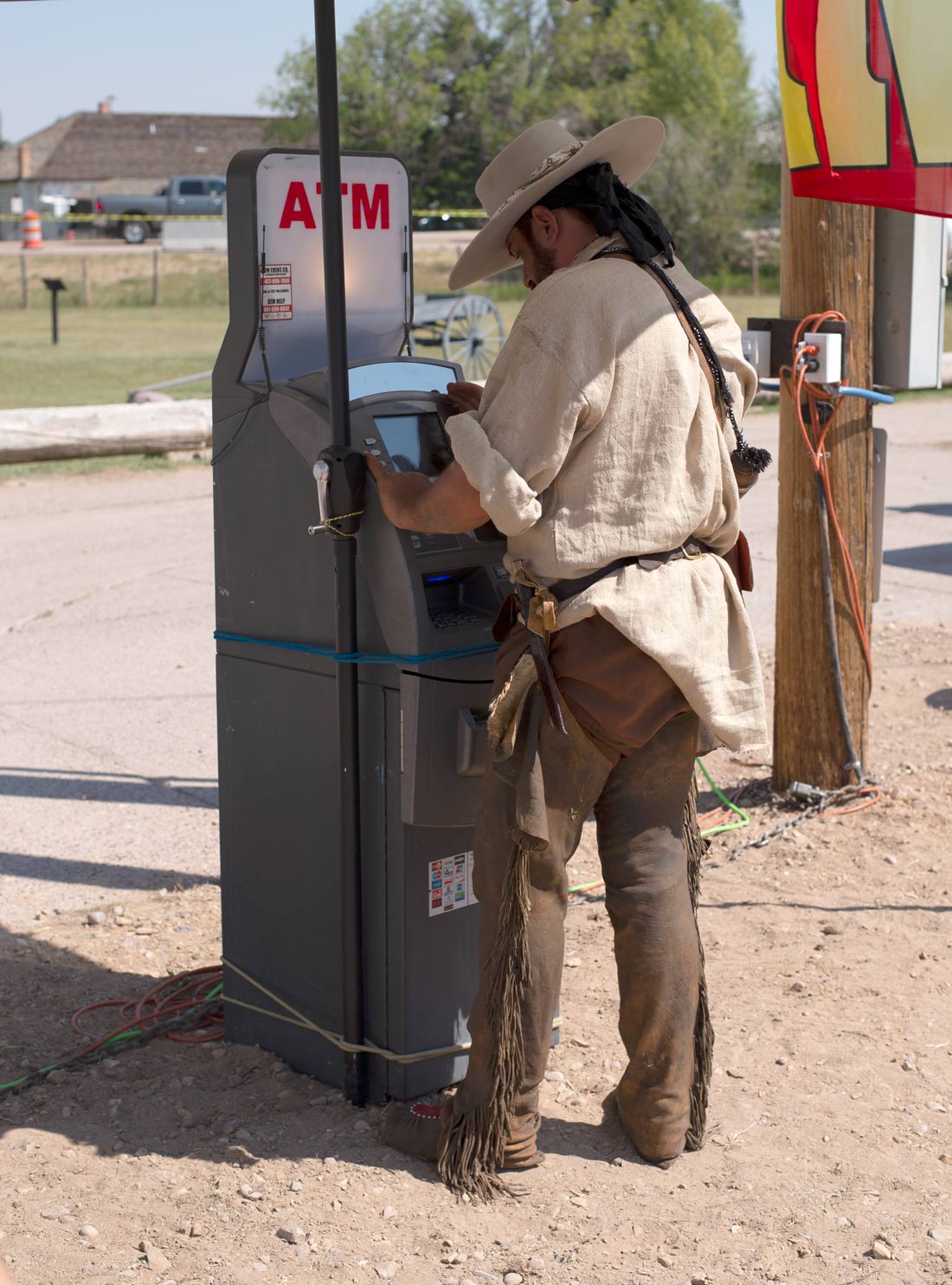

Rugged mountain men in buckskins. Native American dancers. Teepees and campfires. Powder horns. ATM machines.

Wait… what? That’s right, ATM machines. Early 19th century frontier trade meets modern commerce at Fort Bridger, Wyoming, every Labor Day weekend as mountain man wannabees gather at the fort's mountain man rendevous.

A mountain man reenactor gets cash from an ATM machine at the Fort Bridger Rendevous. The pictures in this blog are from a past rendevous.

This year’s rendezvous, a annual celebration of the fur trade rendezvous that brought together mountain men on the Green River in the early 19th century, will be held Aug. 29-Sept. 2.

The rendezvous gathers reenactors who wish they were born, or at least could spend an occasional weekend, in the Wild West as it was two centuries ago. In weather that can be as hot as blazes, they swagger about in fringed buckskins and broad-brimmed hats, with strings of beads around their necks, scruffy beards and steely-eyed gazes toward the horizon.

A rendevous reenactor.

Some spend the weekend sleeping in teepees. Country music performers, Native American dancers, candy shot from cannons, cook-offs, black powder rifle shooting, knife-throwing, and campfire-building are a break from the buying and selling. Crowds of attendees also can stroll through the historic buildings at Fort Bridger, including a museum in the stone barracks.

The rendezvous, like those of old, is still a gathering to buy and sell. Dozens of vendors hawk pre-1840s replicas of leather canteens, powder horns, knives with hand-carved handles, animal hides, buttons made of animal horns and a variety of other historic gear. No post-1840 items are sold at the event.

A vendor at the rendevous and, below, powder horn and leather canteen replicas for sale.

The colorful rendezvous is a look back at a global trade that once opened the way for European Americans to settle the West, fueled American industrialization, brought profound changes to Native American life, provided the impetus for the tragic development of the southern plantation system and slavery and depleted the continent’s population of fur bearing animals such as the beaver and sea otter. The fur trade is a fascinating cautionary tale about the effects of global trade, with surprisingly contemporary overtones of trade wars, environmental concerns and income disparities.

Before European colonization of the Americas, Russia controlled the fur trade, supplying pelts to Western Europe and Asia. The trade developed in the early Middle Ages (500-1000). Between the 16th and 18th centuries, Russians began to trade with native populations in Siberia for Arctic fox, lynx, sable, sea otter and stoat (ermine) fur pelts. In a search for sea otter pelts prized in China and later for the northern fur seal, Russian traders expanded into Alaska.

North America’s fur trade between Europeans and Native Americans began as early as the 1500s, when European sailors began trading metal tools for beaver pelts that the sailors used as sewn-together blankets to keep them warm on their voyages home. They then sold the pelts to hat makers who valued the beaver’s soft waterproof under fur. The trade was established by 1580 in France and soon after in England as Hugenot refugees from France took hatmaking skills to England. Beaver felt hats were an expensive status symbol, and beavers had largely disappeared in Europe and European Russia as a result. Fur was used to make warm clothing before the distribution of coal for heating.

A reenactor in a top hat. The North American fur trade focused primarily on beavers for beaver hats, sea otter pelts for the China market and deer skins.

The Russians not only traded in fur but collected fur tribute from Siberian tribes. Furs, called “soft gold” because they provided hard currency and tribute income, were Russia’s largest source of wealth in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Fur was in great demand in Western Europe because European forests had been over-hunted and furs were extremely scarce. Fur allowed Russia to purchase from Europe metals, textiles, firearms and sulfur and to trade with Middle Eastern countries for silk, textiles, spices and dried fruit. From 1585 to 1680, tens of thousands of sable and other valuable pelts were obtained in Siberia annually. As the demand increased, violence and force rather than trade became the main means of obtaining furs.

Furs were sent from Virginia to London in the 1600s. The New England fur trade expanded along the east coast. In the late 1600s, the Hudson Bay Company was established with a monopoly to trade into all of the rivers that empty into the bay. The company sent two or three trading ships into the bay annually that brought back mainly beaver furs.

In the English southern colonies, a deerskin trade was established around 1670, based at the port of of Charleston, South Carolina. Europeans traded Native American hunters deerskins for European goods at huge profits - axe heads, knives, awls, fish hooks, cloth, woolen blankets, linen shirts, kettles, jewelry, glass beads, muskets, ammunition and powder. A metal axe head was exchanged for one beaver pelt which could be exchanged in Europe for enough to buy dozens of axe heads in England. Natives replaced their stone axe heads made by hand with iron ones, so they benefited substantially as well. Colonial trading posts in the southern colonies also traded alcohol, especially brandy and rum. The British saw the ill effects of alcohol on the native population and banned the sale of alcohol to Native Americans in Canada. Rum negatively affected the social behavior of Native Americans and contributed to skirmishes with other tribes and Europeans. Alcohol, provided on credit, led to a debt trap for many. If they couldn’t collect enough deerskins to pay the debt, they were sold into slavery along with their wives and children.

Trade forged alliances between European and native cultures. Fur traders married high-ranking Indian women, while trappers and other workers in the trade had relationships with lower-ranking women. It was common for Native American women to offer marriage in exchange for fur traders not trading with rival tribes. Marriages built long-term relationships that ensured the continual supply of European goods and discouraged fur traders from dealing with other tribes. Fur traders marrying the daughters of chiefs would ensure the co-operation of an entire community as well as kinship and clan networks. Native Americans also were more likely to share food, especially in the winter, with fur traders regarded as part of their communities. Fur trading companies encouraged their employees to marry Native Americans, partly for trade relations but also because an employee with a wife had to buy more supplies from the company.

A teepee at the rendevous. Fur traders became closely linked and in some case married into native American tribes. They often lived in teepees and adopted many Native American customs.

Traders’ accounts often mentioned bartering goods with Native American women in exchange for canoes. Some tribes traveled hundreds of miles by canoe to sell fur and bring home European goods. While they were gone, women ran their communities. Flotillas of up to 200 canoes would arrive at a location to barter fur for goods. In some societies, women were used to carry fur pelts overland and became essentially slaves.

Many of the mixed-race descendants of fur traders and Native American wives developed their own culture, now called Métis in Canada, based on the fur trade. Those in the Canadian Red River region were so numerous that they developed a creole language and culture. Since the late 20th century, the Métis have been recognized in Canada as a First Nations ethnic group. Interracial relationships resulted in a two-tier mixed-race class, in which descendants of fur traders and chiefs achieved prominence in Canadian social, political, and economic circles while lower-class descendants formed a culture based on hunting, trapping and farming.

Native Americans supplying the robust European demand for deerskins became dependent on manufactured goods such as guns and domesticated animals, and lost many traditional practices. An inequality gap appeared in tribes as some were more successful hunters and traders than others.

In the 18th century, Native Americans arose against fur traders in the southeast, almost wiping out European colonists there. The British defeated the tribes with help from the Cherokees, and the tribes then returned to making alliances with the European powers for the best deals they could get. The British promoted competition between tribes, and sold guns to both Creeks and Cherokees. Tribes would raid each other and sell prisoners into the colonizers’ slave trade. France tried to outlaw these raids because their Native American allies bore the brunt of the slave trade. Guns and other modern weapons became essential trading items for Native Americans to protect themselves from slave raids. After African slaves began to be imported in larger quantities, the focus returned to the deerskin trade. Fur traders pushed into new areas, waging near genocidal campaigns against some Native American tribes as they went.

By the mid 1700s, when the French and Indian War disrupted trade, the French were driven out of the southeast and the British became the dominate trading power there. Charleston and Savannah became the main trading ports for export of deerskins, and deerskins the most popular export. Charleston got tobacco and sugar from the West Indies and rum from the north in exchange for deerskins. Britain exchanged the deerskins for woolens, guns, ammunition, iron tools, clothing, and other manufactured goods that were traded to Native Americans.

The Revolutionary War disrupted the deerskin trade, which was declining because of over-hunting.

When the British retreated, tribes who had fought on their side had to make trading deals with the new country. Many were subject to violence from European Americans who sought to settle their lands. As the value of deerskins dropped, many tribes went into debt and began to sell their land to pay their debts and acquire European goods upon which they had become dependent. This contributed to resentment and warfare against European settlers.

As men from the old fur trade on the coast went west in the early nineteenth century, they sought to recreate the same economic system. Marriage with native women played an important role in the western fur trade. Many of the children of these marriages had multiple Native American heritages and some were involved in the Lewis and Clark expedition. They possessed both native and European skills, spoke multiple languages, and had the required kinship networks. In the Rocky Mountains, they congregated around trading posts where they were employed as packers, laborers or boatmen. They established a whole economic system around the bison trade and the production of buffalo robes in the 1840s and influenced the rapid bison depopulation.

Native American dancers at the rendevous, above and below.

At the same time as the inland trade was spreading West, a ship-based maritime fur trade was growing that focused on acquiring furs of sea otters and other animals from Native American peoples of the Pacific northwest coast and Alaska. These furs were traded mostly in China for tea, silks, porcelain and other Chinese goods which were then sold in Europe and the United States. The Americans and British entered this trade in the 1780s. It boomed around the turn of the 19th century before declining and finally ending in the mid to late 19th century. It depleted the sea otter population.

The maritime fur trade was an international trade network that linked the Pacific northwest coast, China, the Hawaiian Islands, Britain and the United States, especially New England. The trade made the native coastal peoples wealthy, but also led to increased warfare, slavery and the spread of European diseases among them. The influx of the fur trade profits contributed to New England industrializing, especially in textile manufacturing. This in turn increased the demand for cotton, making possible the rapid expansion of the cotton plantation system and slavery across the South.

The best pelts were northern sea otters, which were hunted to local extinction before the fur traders shifted to California and depleted the southern sea otter population to meet the voracious Chinese demand for fur for trim on robes. The British and American traders shipped their furs to Canton, China, while the Russians sold theirs to the Chinese in a Mongolian trading town, Kyakhta.

Global demand for Chinese tea was a primary reason for a shortage of silver, the only currency that the Chinese who were the sole producers of tea at the time would accept. Furs were the third-most lucrative American export to China, behind silver bullion and ginseng. The first American trading vessel to take to China these commodities, the Empress of China, made huge profits on the voyage in 1785 and inspired other Americans to make similar journeys. Americans dominated the maritime fur trade, making at least 127 voyages between the United States and China via the Northwest coast. During the late 1810s, the return on investment ranged from about 300% to 500% and returns of 525% were common.

Ships sailed from Boston to the Pacific via Cape Horn, then to the Northwest coast, arriving in spring or early summer. They spent the summer and early autumn fur trading. In late autumn, they sailed to the Hawaiian Islands to spend the winter. They then sailed from Hawaii to Macao on the coast of China, arriving in autumn. Trading in Canton began in November, when tea shipments were ready. Trading took weeks or months, after which the ships were loaded with Chinese goods. They left in the winter and used the northeasterly monsoon winds of the South China Sea to reach the Sunda Strait, then the southeasterly trade winds to cross the Indian Ocean to the Cape of Good Hope. From there the ships sailed to Boston.In later years, additional markets and side voyages were added.

Traders supplemented the trade by expanding the pre-existing local slave trade. Traders would purchase slaves inexpensively around the mouth of the Columbia River and in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, then sell or trade them further north at a high profit. Some made more money selling slaves, rum, and gunpowder than from fur trading.

Before the 19th century, Chinese demand for Western goods was small, but the Chinese accepted bullion, resulting in a drain of precious metals from the West to China. This reversed in the early 19th century as Western demand for Chinese goods declined when coffee from the West Indies began to replace tea in the United States. Chinese demand also increased for English manufactures, American cotton goods and opium which was outlawed but smuggled into China. China was being drained of silver and saturated with Western goods. Too many American and British companies speculated in the market, resulting in bankruptcies and consolidation in the 1820s, then the plummeting of tea prices, the fall of China’s trade by a third and a decline in sea offer pelts from over-hunting. The trade's boom years ended.

In 1834, John Jacob Astor, who created the huge monopoly American Fur Company, withdrew from the fur trade as he saw the decline. The United States regulated trading with Native Americans and issued licenses for trade in the Indian Territory, which was most of the United States west of the Mississippi River. Early ventures into this territory were often fur-trading expeditions, many of which were the first recorded instances of Europeans reaching regions. As marine furs became depleted, American ship captains began accepting increasing numbers of land furs such as beaver. In the early 19th century, American traders sold 3,000 to 5,000 beaver skins to Canton annually and 10,000 annually by the early 1930s.

After the 1846 resolution of the Oregon Territory controversy between the United States and England and the American purchase of Alaska in 1867, American hunters returned to hunting sea otter and contributed to their near-extinction throughout the Aleutian and Kuril Islands.

The fur trade transformed intertribal relations, trade and war. Traditions such as fabric appliqué, engraved silver jewelry as native craftsmen learned to make jewelry from coins, and iron tools that made possible the creation of large totem poles began as a result of the trade. Vermilion from China replaced earlier red pigments and can be seen on artifacts from this era. The natives became integrated into a global market economy and also began to sell salmon, lumber and artwork to traders. Native dress shifted from furs to imported textiles. Firearms made hunting much more efficient but warfare much more deadly.

The Hawaiians were generally receptive to Western incursion. The rise of King Kamehameha I and the unification of the islands under his rule were made possible in part by the effects of the maritime fur trade. The influx of wealth and technology helped make the new Kingdom of Hawaii relatively strong. Many non-native foods were introduced to the Hawaiian Islands, including beans, cabbage, onions, squash, pumpkins, melons, and oranges, as well as cash crops like tobacco, cotton, and sugar. Animals introduced included cattle, horses, sheep, and goats. The native population suffered epidemic disease, including cholera. The availability of alcohol led to its widespread consumption. These issues plus warfare related to the unification of the islands, droughts, and harvesting of sandalwood taking precedence over farming contributed to famines and a population decline of 50 percent by 1850.

The effect of the maritime fur trade in southern China was probably not significant and mostly limited to coastal producers and merchants. The maritime fur trade was for the United States a branch of the Asian trade based in Salem, Boston, Providence, New York City, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. It focused on Asian ports such as Canton, Calcutta, Madras, Manila, Jakarta, and the islands of Mauritius and Sumatra. Goods exported included furs, rum, ammunition, ginseng, lumber, ice, salt, Spanish silver dollars, iron, tobacco, opium, and tar. Goods brought back from Asia included muslins, silks, nankeens, spices, cassia, porcelain, tea, sugar, and drugs. The Asian trade resulted in accumulation of large amounts of capital in a short time, which led to the aforementioned textile mills and expansion of plantations and slavery.

A reenactor with money tucked in the brim of his hat. The fur trade was highly profitable, laying the foundation for a number of American fortunes and providiong funds for the industrializaton of New England.

The mountain men went west overland primarily to trap beaver. St. Louis, Missouri, was a base for them to form trading companies. Merchants met trappers and Native American traders there and exchanged goods marked up between 200 and 1,000 percent – salt, sugar, tobacco, traps and liquor. Native Americans traded for knives, guns and blankets. People also drank, gambled, told stories and fought at the rendevoux, which lasted for two weeks or until trading was complete.

Rendevoux were most common in the Rocky Mountains from about 1810 through to the 1880s. About 3,000 mountain men ranged the mountains between 1820 and 1840, the peak beaver-harvesting period. Most were employed by major fur companies. The rendezvoux attracted as many as 450-500 European American trappers and traders working in the Rockies along with many Native Americans.

Among the fur traders was an orphan named Jim Bridger who was part of the second generation of mountain men and pathfinders who followed the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804. At age 18, he responded to a newspaper ad to join a fur trapping expedition that included Jedediah Smith and other famous mountain men. Bridger thereafter participated in numerous expeditions. He explored the Rocky Mountains from southern Colorado to the Canadian border. He spoke passable French, Spanish and several Native American languages, although he was illiterate. He knew Kit Carson, George Armstrong Custer, John Frémont, John Sutter, Jedediah Smith, and other famous mountain men.

Bridger’s initial employer, William Henry Ashley of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, had company representatives who hauled supplies to specific mountain locations in the spring, traded the goods with trappers for furs, and brought pelts back east to St. Louis and other locations on the Missouri and Mississippi rivers in the fall. Ashley eventually sold the business to Smith, who later sold it to Bridger and his associates.

Far from venturing out as loners into a wilderness, the mountain men often traded and trapped in groups. They endured freezing weather, dangerous navigation through wildernesses, attacks by hostile Native Americans, wild animal encounters and food shortages. They used herbal remedies, set their own broken bones and tended to their own wounds. They knew how to catch fish, build shelters and hunt. They wore stiffened deer skins that protected them from enemies’ weapons and were armed with guns and knives. They had shoulder length hair, scraggly beards and sun-burned faces. They spread knowledge of the West and opened emigrant trails which eventually expanded into wagon roads used by people settling the West.

Bridger’s company was once attacked by Native American warriors who killed 15 of them. He was among the first North American-born colonial frontiersmen to see Yellowstone’s geysers, and some believe he was the first European American to see the Great Salt Lake. He thought it was an arm of the Pacific Ocean.

Mountain men bought furs from Native Americans, mingled with them and adopted many of their manners and customs. The rendevoux, including ones on the Green River in Wyoming, were annual trading conventions at which traders met Native American trappers and exchanged goods for beaver pelts. Hatters bought some 100,000 American beaver pelts annually for $6-9 a pelt. Beavers also were used for castoreum, a perfume base.

British companies trapping in the Pacific Northwest tried to confine American trappers to the Rocky Mountains, which gave rise to the term mountain men. Starting in 1834, The Hudson Bay Company visited American rendezvoux and offered manufactured trade goods at prices far below the American fur companies’ prices. This, combined with a declining demand for beaver as silk became the preferred material for hats and beavers were depleted, destroyed the American rendezvous system. The last one was held in 1840. By 1846 only some 50 American trappers still worked in the Snake River country, compared to 500-600 in 1826.

Mountain man Robert Newell told Jim Bridger: "[W]e are done with this life in the mountains—done with wading in beaver dams, and freezing or starving alternately—done with Indian trading and Indian fighting. The fur trade is dead in the Rocky Mountains, and it is no place for us now if ever it was."

Fort Bridger originally was a fur trading area on the Black Fork of the Green River in Wyoming.

The collapse of the fur trade caused many Native American communities to decline. Mountain men began to take jobs as guides for wagon trains, the military and buffalo hunters. Others opened fort-trading posts to service settlers heading west. Bridger and fellow mountain man Louis Vasquez decided to build Fort Bridger in 1842 as a supply and trading post.

Bridger said in a letter in December 1843:

“I have established a small fort, with a blacksmith shop and a supply of iron in the road of the emigrants on Black Fork of Green River, which promises fairly. In coming out here they are generally well supplied with money, but by the time they get here they are in need of all kinds of supplies, horses, provisions, smithwork, etc. They bring ready cash from the states, and should I receive the goods ordered, will have considerable business in that way with them, and establish trade with the Indians in the neighborhood…”

Bridger traveled and traded while Vasquez tended the post. The operation worked well for about a decade.

Fort Bridger today.

The great push west along the newly opened Oregon Trail built up from a few settlers in 1841 to a steady stream in 1844–46, and became a flood as the Mormon migration used the road to the Great Salt Lake discovered by Bridger in 1847–48 and gold was found in California in 1848. Fort Bridger became a resupply point for wagon trains on the Oregon Trail, California Trail, and Mormon Trail.

Bridger was known for giving expert advice to wagon trains passing through, although he missed the mark a few times. When the Donner Party passed by in 1846, Bridger and Vasquez assured them that Lansford Hastings' proposed shortcut was a fine, level road, with plenty of water and grass, with the exception of a forty-mile waterless stretch. The 40-mile stretch actually was 80 miles, and the "fine level road" delayed the Donner Party so that they were trapped in the Sierra Nevadas in the winter.

Bridger was among mountain men who doubted the viability of the Mormon plan to settle Utah, and reportedly told Brigham Young he would give $1,000 if he knew corn could be grown in the Salt Lake Valley.

Bridger had a number of disputes with the Mormons, including one in which a militia from Salt Lake tried to arrest him for violating treaties with Native Americans by selling them alcohol and firearms. Bridger fled east temporarily to avoid arrest.

The Mormons, who had a steady string of wagon trains going through the area to Utah, established their own supply depot nearby, Fort Supply, but claimed to have purchased Fort Bridger from Bridger and Vasquez for $8,000 in gold coins in 1855. A deed registered in Salt Lake City documented the purchase, but Bridger, who was away employed as a guide when the deal was made, disputed it. Bridger’s and Vasquez’ names were signed by a man who claimed to have a power of attorney from them.

In 1857, the U.S. Army was ordered to Utah to install a governor as a replacement for territorial governor Brigham Young and to establish a military presence in Utah. Mormons, alarmed by the U.S. army headed for Utah, first ambushed the army’s supply wagons and destroyed its provisions and then set fire to Fort Bridger to keep it from falling into the hands of the army. The troops showed up to find only smouldering ruins, but they wintered near Fort Bridger and established the fort as an official army post. Bridger guided them to Salt Lake City, and the army installed the new governor without further Mormon resistance.

From 1858 to 1890, the fort was an army post. Civilian William A. Carter was sutler, postmaster, probate judge, and freighting, beef and lumber contractor for the army at the post. Congress ended up rejecting both the Mormons’ and Jim Bridger’s claims to the fort. Still standing at the fort is a Pony Express barn and wall built by Mormons. The fort closed in 1890 and the site became a cattle town. Fort Bridger was made a state historic site in 1933 and several buildings were restored or reconstructed.

Bridger served as a guide for a number of expeditions in the 1850s-1860s. He discovered what would eventually be called Bridger Pass, an alternate route which shortened the Oregon Trail by 61 miles. The pass later became the route across the Continental Divide for the Union Pacific Railroad and Interstate 80.

He was known for his colorful stories, including one about a petrified forest with petrified birds singing petrified songs. He also would tell of being chased by 100 Cheyenne warriors into a box canyon, with warriors bearing down on him. He would then pause, prompting his listener to ask what happened next. “They killed me,” he would reply. The story was similar to the actual 1831 killing of Jedediah Smith by Comanches.

Bridger married three times to Native American women. His first wife died in 1845. He married the daughter of a Shoshone chief, who died in childbirth three years later. In 1850, he married Shoshone chief Washakie's daughter, with whom he had two children. Bridger died in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1881 at age 77.

Places are named after Bridger in Wyoming, Montana, Utah, Missouri, Oregon, Nevada and Idaho. They include the fort and nearby town, mountains, a wilderness, a ski area, a national forest, a pass, a lake, a region, schools and an annual rivalry between Utah State University and Wyoming. The winning team receives a .50-caliber Rocky Mountain Hawken rifle, the "Bridger rifle", as a traveling trophy.

The Fort Bridger Rendezvous has been held annually since the 1970s and is one of the largest mountain men rendezvoux in the West. It is organized by the Fort Bridger Rendezvous Association.

Modern fur trapping and trading in North America is part of a $15 billion global fur industry in which wild animal pelts make up only 15 percent of total fur output. Today’s fur trade is based on pelts produced at fur farms and regulated fur-bearer trapping. Animal rights organizations oppose the fur trade, saying animals are brutally killed and sometimes skinned alive. Fur has been replaced in some clothing by synthetic imitations. The beaver population remains a tenth of what it once was, and the sea otter is classified as an endangered species.

A Native American child at the rendevous.

Check out these related items

Springtime in the Rockies

It's springtime in Utah's Rockies. Photographer Forrest Anderson captured the stunning scenery.

The River That Keeps on Giving

The mammoth Colorado River is the lifeblood of the southwest United States, supplying water and power for cities and agriculture.