Dinosaur Gateway

Photos by Forrest Anderson

Dinosaurs are among the coolest creatures ever, but they’re also elusive. Even if you squint your eyes and use your whole imagination, it can be difficult to put flesh on those massive bones standing in front of you at a museum.

Time to head for the George S. Eccles Dinosaur Park in Ogden, Utah, a Jurassic Park where more than 70 full-sized dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals roam, cool their heels in a pond, and keep watch over their eggs.

These scientifically correct dinosaur sculptures teach paleontology the fun way – by showing visitors of all ages what it is like to be eye to eye with a stegosaurus or walk between the legs of a brontosaurus.

Utah has some of the world’s richest dinosaur fossils, and the state is obsessed with the ancient beasts. Of more than a thousand known species of dinosaurs, about 115 were discovered in Utah. Several world-class museums and dinosaur quarries in the state concentrate on Utah's dinosaurs, but the Eccles park is the only one that provides a broad vision of the size, appearance and behavior of dinosaurs worldwide. The park is the place to start if you want an overview of the dinosaur world before heading out on a hunt for Utah's dinosaurs.

The park also is a gateway to paleontology addiction, as one of its main goals is to hook children on paleontology from an early age. In addition to the giant models, the park runs a variety of science events and day camps for children and families.

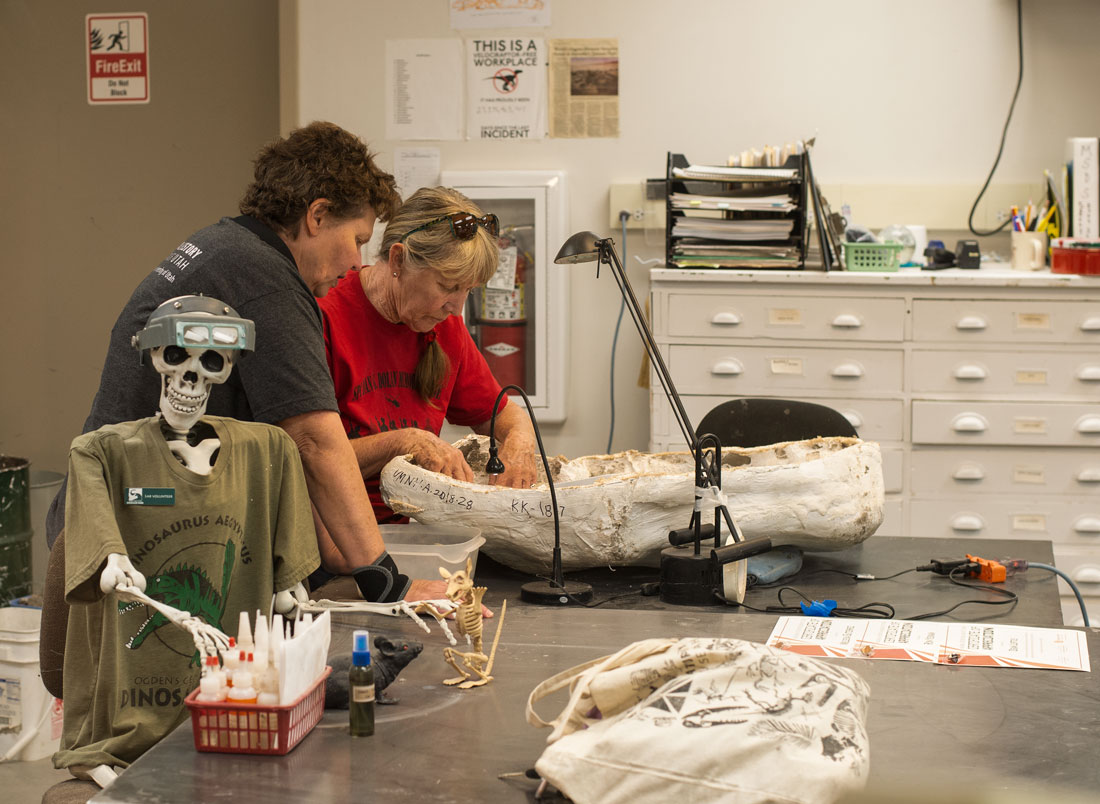

Student volunteers are taken into the paleontology lab and taught to clean bones and remove them from the casing used for transport using drills and toothbrushes. They learn the specialized skills required to get the bones out of rock, as well as being the first people to see fossils that no human eyes have seen before.

The paleontology lab in the park's museum.

The park also holds holiday events, including a Carnivore Carnival at Halloween among the giant sculptures and Christmas events during which the sculptures don Santa hats.

If the park's guides are any indication, the strategy works. One guide at the park’s museum who we talked to, a young man named Ryan, said he had been working at the park since he was eight years old and has been obsessed with paleontology ever since. Ryan exhibited an encyclopedic knowledge of the park museum’s specimens. He told us where each specimen came from and its fascinating back story. The museum has specimens from all over the world. Ryan knew whether a skeleton came from the island of Madagascar or Wyoming, when it lived, whether its parts were all from a single skeleton or assembled from several animals, and the characteristics that represented its species or that were unique to it. We learned that dinosaurs that lived on islands were miniaturized versions of ones on continents. Flicking a laser pointer over the skeletons, Ryan showed us where one enormous skeleton had had arthritis and that another has a shoulder bone borrowed from a similar species because its original shoulder is missing.

He pointed out the differences between the long tail bones of a normal Camarasaurus and one that had spina bifida. Wait! Dinosaurs had spina bifida? Ryan’s approach, telling the stories of individual dinosaurs, bridged the millions of years between us and them.

A normal Camarasaurus tail in back, and one with spina bifida in front.

His fellow guide Ron, an Indiana Jones in a brimmed hat and jacket, wasn’t a step behind him in spilling out fascinating details about the specimens at top speed.

In the park outside, the enormous detailed sculptures are based on actual fossils and an outpouring of new data on dinosaurs that has come to light in recent years. They exemplify the power of “showing rather than telling” that makes a compelling science museum. The sculptures, along with roaring sound effects from speakers placed throughout the park, provide the entertainment. Labels next to them provide the science, describing where the animals were found, the era in which they lived and what is known about their behavior.

A T. Rex with its fresh kill.

The life-sized sculptures are created by paleo-artists. These sculptors specialize in using assembled scientific information about a species to create a model of it. The model is then scaled up to create a life-sized fiberglass and industrial styrofoam version.

One of the park’s major challenges and opportunities is that paleontology in Utah and worldwide are evolving at top speed as new species are found and the worldwide fossil record grows. The park has an iterative approach – the sculptures are modified or added to as new information about species becomes available. Some models are based on hundreds of fossils and others on just one specimen, only part of which may be extant. The models are detailed – with skin textures, colors and behavior that sometimes are an educated guess and sometimes can be verified through fossils, sophisticated bone scanning and chemical analyses. Paleontology has always depended on a certain amount of imagination to piece together animals from partial skeletons, but the park continuously updates its exhibits to reflect the developing nature of the field.

In 2019, the park got a new Utahraptor because research revealed more details about what a Utahraptor looks like - that it had feathers and a stance like a chicken. The raptor was placed next to an older model to make the point that science is always evolving.

A Utahraptor on the hunt in the park.

A Tanystropheus, a 20-foot-long reptile with an elongated neck, also was added. Scientists think that the creature used its neck to dip its head into the water and catch fish on shorelines.

A Brachiosaurus model got a re-sculpted skull to reflect new discoveries about the species, and other models got repairs and fresh coats of paint.

One of the park’s most dramatic models arrived in 2017 – a 20-foot-tall Spinosaurus. The species had been discovered in Egypt in 1914, but had reemerged as a hot topic in paleontology in 2014 when a team of scientists found some of the animal’s bones in Morocco. The new find opened a debate about whether the Spinosaurus could move both on land and in the water. The life-sized Spinosaurus model at the park was created at a cost of some $200,000, using a 1/9th size model created by the artist as a guide. When we were there, the Spinosaurus was getting repairs to part of its tail.

Texture on the Spinosaurus' back.

The George S. Eccles Dinosaur Park also is an interesting example of a city government and other organizations joining together in a cooperative effort to make a respected science museum which attracts visitors from far beyond the local area. The park began in 1993 as an outdoor walkway, and expanded with funding from the George S. Eccles Foundation. The indoor museum and other facilities were added. Local businesses and other organizations in addition to scientific grants have helped fund sculptures. The park attracts more than 150,000 visitors a year, although the numbers dropped this year because of the pandemic.

In addition to the dinosaurs, the museum has a beautiful collection of gems, including sparkling purple geodes that are as tall as an adult, jewelry and gems from all over the world.

The museum has specimens from the Permian through Cretaceous periods, including crawlers, predators, marine creatures, flying reptiles and others. It couldn’t be located in a better place - the park itself was once dinosaur habitat, as dinosaurs roamed all over Utah during the Mesozoic Era 225 to 65 million years ago.

Check out these related items

Utah’s Rock Stars

Utah's spectacular scenery harbors one of the world's most complete and diverse dinosaur fossil records.

California’s Sea Monsters

In fall and winter, tens of thousands of elephant seals make a migration to California's coastal rockeries to breed and give birth.

Feathers of a Bird

Of all creatures, only birds have feathers. These delicate, sophisticated, beautiful structures perfectly combine form and function.

The Elephant Needs the Room

Despite tough bans on ivory trade, Africa's elephants are declining in numbers because of poaching and trafficking of illegal ivory.

Saving the Great Salt Lake

The Great Salt Lake, along with other saline lakes worldwide, is drying out. Preserving and restoring won't come cheap.