Portraits of Mary

Photos by Forrest Anderson

Probably the world’s most prominent icon is that of Mary, the mother of Christ. Images of Mary are ubiquitous throughout Europe, the Americas and parts of Africa and Asia.

The name Mary in various versions - Marie, Maria, Mariah, Miriam, Marianne, Marian, May, Maia, Mia, etc. - has been one of the most popular female names for hundreds of years. At least half of my own female southern French ancestors were named Marie.

Countless towns, villages, churches and schools are named after Mary. Her image is built into houses, walls and cathedral facades. Entire galleries in famous museums are filled with art depicting Mary. She occupies a central place in religious music and literature. Mary permeates annual festivals in Latin America and the Philippines. Shrines dedicated to her are scattered throughout the world. Her image still influences fashion and wedding traditions.

Her influence spills over into Judaism, Islam and Buddhism and has spread with the Internet. Even largely non-Christian nations such as Japan have famous versions of her such as the Lady of Akita, a wooden statue associated with miracles.

Once the center of several Christian feast days, Mary now is widely seen as the religious face of Christmas. In the hands of the world’s greatest artists, her image has been developed and crafted over almost two millennia into a global brand.

A painting of Mary as the altarpiece of a church in Beijing, China.

The Biblical account of Christmas says that Mary was a young Jewish virgin in Israel who was called by an angel to become the mother of Christ and gave birth to him in a stable in the town of Bethlehem. After local shepherds were informed in a heavenly vision of Christ's birth, they went to see the new borne Child. Later, wise men who God had told of Christ’s birth visited the Child and his family and gave him gifts. Their visit tipped off then-King Herod that a potential rival had been born, and Mary, her husband Joseph and the child had to flee for safety to Egypt for an unknown period. They later returned to the Holy Land and raised Christ in the town of Nazareth. Mary was present at a few events in Christ’s adult life and at his crucifixion.

A Jewish revolt against Roman rule resulted in Jerusalem's destruction in 70 AD. This was followed by another revolt that prompted the Romans to ban Jews from settling in Jerusalem after 135. Many Jewish Christians settled in other lands. In this Christian diaspora, narratives of the origin of Christianity became important. By the end of the first century, there were four written accounts of Jesus’ life and ministry which we call today the Gospels. Two of them deal only with Christ’s adult life. Luke’s account is the most detailed about Mary, but still gives no details of her childhood and family. Mark and John give sparse attention to Mary. She appears just once in the book of Acts, when Jesus’ followers pray after his death. Paul refers to her once in his writings.

Onto this skeletal account has been added an avalanche of cultural and religious tradition in the form of apocryphal stories, accounts of Mary appearing in visions, and accompanying art and music.

Stories about Mary first emerged among early Jewish Christians, who cherished the prophecy of Isaiah that a virgin would conceive and bear a son and call his name Immanuel. The Hebrew word meant maiden, but the Greek Septuagint translation was virgin. This topic sparked intense arguments among these followers and between them and Jews about Jesus’ conception and birth.

Apocryphal writings fleshed out Mary's childhood with the names of her parents, and the story that she was taken to be raised in the temple at a young age and wove the veil for the temple. Beyond these narratives and attempts to explain the virgin birth, however, Mary drew little attention from early Christians.

That began to change when Christianity was recognized as lawful in 313. The emperor Constantine converted to Christianity, and the Emperor Theodosius made it the empire's official religion in 380. Its new status as state ideology meant that the empire became involved in determining what Christianity was and how it fit into the empire’s agenda. The emperor presided over great assemblies to discuss and legislate the religion and develop an official orthodox version of Christianity. Christianity was reimagined as a pervasive, hegemonic political religion. This included persecuting those who disagreed. The central topic became the nature of Christ, his dual divinity and humanity and his position with regard to God the Father and the Holy Ghost. This involved the circumstances of his birth and thus Mary.

Constantine summoned bishops, prominent scholars, and officials for a council in Nicaea on the Bosphorus. They formulated a statement of faith to govern all Christians in the empire. It secured for Mary the role of Mother of God. The council's decisions were sent to all Christian bishops. The Nicaean Creed sparked heated discussions on Christ’s nature over the next century. The unifying of Christian doctrine suppressed a variety of other traditions about Christ and Mary. Among them was the belief that Mary did not retain her virginity after Christ's birth, but went on to have other children by Joseph. Early Christian supporters of this view argued that baptism, not virginity, made all Christians holy.

As Mary became the perpetual virgin, life-long virginity was elevated and it contributed to the rise of convents and monasteries. She became a model and companion to those who chose to live as virgin ascetics. Mary also became the model of a meek, humble, hard-working woman cloistered at home.

She became a central marker of the differences between Christians and Jews, who scoffed at the notion of a virgin birth and claimed Mary actually had been sexually immoral. She also was reimagined as a triumphant figure crowned and enthroned as the imperial Mother of God and unifying symbol of the empire.

Constantinople's patriarch, Syrian monk and Biblical scholar Nestor (381-c.451), didn’t believe that devotion to Christ as an all-powerful God left room for Mary as a goddess-like figure. He condemned the use of the term Theotokos, or Bearer of God, for Mary. Supporters of the term were Proclus, a close associate of the emperor’s sister, and Cyril, bishop of Alexandria, who jumped at the chance to diminish Nestor and gain imperial favor. Cyril persuaded the emperor to summon a council to Ephesus, where local tradition claimed Mary had died and once the center of the cult of the goddess Artemis. Cyril's views won the day after he gave gifts to win members of the imperial court to his side. Nestor was exiled and Proclus promoted to patriarch of Constantinople-in-waiting. Mary became linked to the doctrine of Theodokos. The Emperor Theodosius II's sister took a vow of virginity as a devotee of Mary, founding churches and giving them gifts, such as her own robe to the Hagia Sophia.

The Council of Chalcedon of 451 further defined Mary as the virgin God-Bearer. Mary’s image as Theotokos spread through Europe on coins, in liturgies, and in icons. This tradition persisted and later lent imagery to such royal figures as Elizabeth, Britain’s Virgin Queen. Mary became the emperor’s patron and part of court ceremony. She was painted and sculpted on architecture as the symbol of the empire.

The emperor Constantine’s mother, Helena, was a devout Christian who transformed neglected sites where Christ had lived into Christian shrines. Under her patronage, stories of Christ’s life were officially embellished and churches built on each site. Mary became associated with Helena's work as well as an emphasis on virginity over other virtues. Mary also was associated with Egypt's indigenous mother goddess, Isis, who was popular in the Mediterranean world.

Little art of Mary apparently existed to this point and almost none from before the eighth century is extant. There are early third-fourth century catacomb paintings of her seated with a child on her lap and a veil on her head, carved ivory diptychs used for private devotions, a tapestry depicting Mary enthroned, a page from a sixth century Syriac Bible that shows Mary in court attire and Isis-like Egyptian images of her and the Christ Child. Mary wasn't the most prominent figure in Christianity, which tended to focus on martyrs.

However, she became a symbol of imperial rule in conquered locations. Emperor Zeno (d. c.491) marked the Christianization of the Samaritans with construction of a church to Mary as Theotokos on Mount Girizim on the site of the Samaritans’ holiest temple.

The narrative developed that she died on Mount Zion and the apostles carried her for burial west of Jerusalem. When Jews attacked the procession, a miraculous wall of fire protected it. Some attackers begged Mary for help and converted to Christianity. The site became a pilgrimage destination, along with the supposed site of her tomb and a place where she was believed to have rested on the way to Bethlehem. Pilgrims flocked to the Holy Land, where they acquired artefacts and images. Among them were reliquary boxes decorated with scenes from Christ’s and Mary’s lives.

One of the most famous was Mary's robe, which two brothers claimed to have stolen from a woman who kept it in a room that was bathed in light and emitted fine fragrances. The emperor had a church built to house it in the Blachermae Palace in a silver and gold reliquary. It later was credited with saving the city from invaders. Mary became Constantinople's protector. Her belt, which she was believed to have dropped to the apostles when she ascended to heaven, also was kept in a church in the city. Constantinople thus became the center of Marian worship.

In Rome, Mary was Maria Regina, a richly dressed queen. She was venerated but to a much lesser extent than in the East. The Pantheon was transformed into the Church of St. Mary and all Martyrs in 609. Later in Renaissance times, the building became a tomb and was adorned with paintings including images of Mary. It still is a church. Mary was positioned as the enemy of heretics and protector of true faith. Marian feasts were incorporated into the Roman liturgy. The resurgence of images of her in Rome meant that the bishop of Rome became the defendor of icons representing her when Byzantine Emperor Leo (c. 680-741) decided that holy images were idolatrous. Under the popes, the number of churches devoted to Mary grew. Images were treated like relics and prayed to, visited and displayed in processions.

After Byzantine power faded in the Muslim conquest of the Mediterranean in the seventh century, Rome’s bishops turned to Frankish rulers for protection and they appropriated Mary as a symbol. Her image accompanied rulers into battle and to coronations and royal weddings. Icons of her adorned monasteries.

In 692, a church council banned the making of some icons. After 754, laws dictated that images and icons be removed, whitewashed, burned or hidden in Asia Minor. Empress Irene, a Mary devotee, convened a second Council of Nicaea in 787 to reverse the ban.

After Charlemagne became Holy Roman Emperor in 800, a dispute in his court ensued over appropriate display of images of Mary. The upshot was that court artists produced ivory images that depicted Mary as enthroned and majestic. In the Byzantine east, which had spent a century soul searching over how to represent Mary, icons reemerged as objects of protection and communication with the divine. They again depicted Mary as Theotokos, seated on a throne in the company of the emperor and on imperial coins.

Mary also became one of the holiest women of Islam, in which a pantheon of dieties from Judaism and Christianity existed alongside Mohammed. Muslims acknowledged Jewish and Christian prophets, but believed that Allah was the only God so Jesus could not have been divine. The Koran mentions Mary more than the gospels, but never calls her the Virgin Mary. The Koran’s position was that the Jews hated Christ so much that they defamed Mary, but the Christians elevated Christ to too high a status. The Islamic Suryat Maryam is an account of the Annunciation and Nativity. Muslims often worshipped at Marian shrines. Mary became a meeting place between Islam and Christianity.

Large sections of the western Empire became separate kingdoms as the empire broke down. Converting to Christianity, the kings of these domains developed court cultures that venerated Mary.

Charlemagne's kingdom spread through conquest, its subjects required to believe in God the Father, his Son and the Holy Ghost. The Virgin Mary was a key tenet of this requirement. Marian feasts for her Purification and Assumption were required. The feast of Mary’s Purification in 814 may have been the day on which Louis the Pious (778-840), Charlemagne’s son, was crowned, and from which he reckoned his reign-years. Many of his annual assemblies met on that day. After Charles the Bald (823-77) promoted Mary as the religious theme of his court in imitation of Charlemagne, Marian devotion became a form of commemoration of ancestors in the court.

Frankish monasteries spread Christianity north and east beyond the borders of the ancient Roman world, with Mary as a figure for veneration. In the British Isles, Mary was depicted as the mother of the suffering hero, the mater dolorosa. She was high born and chaste, intervening for her adherents with her Son in heaven.

Mary's position was not prominent, however, until the early centuries of the second millennium, when Europe had a commercial revolution, the population doubled and new towns and cities were founded. Christian culture was the ideological framework for this urban growth. New architecture, rituals, art and music became the environment for family and community life. Cathedrals, monasteries, churches, feasts and forms of worship arose with Mary as a central figure. New images of her traveled on trade networks. Communities became parishes with rituals that governed people’s lives from cradle to grave.

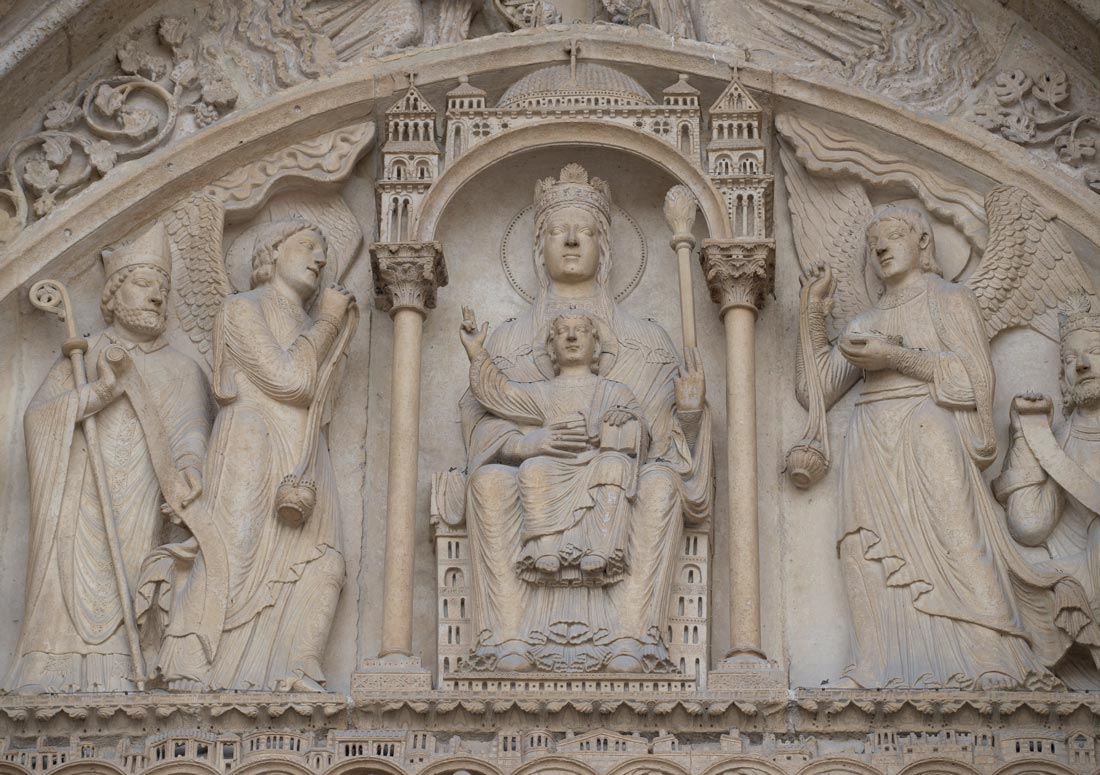

Mary as the symbol of the French nation above the door on Notre Dame of Paris, France's national cathedral.

Monasteries became trend-setting centers of wealth and culture in which learned people explored Mary in various languages. As estates, villages and small towns grew, they had increased wealth to make religious artifacts. When new villages were founded, people built churches that were most often dedicated to Mary. Marian processions were held in villages and towns, with Mary as a combination of local interpretations and universal aspirations. What were purported to be ancient relics of Mary were discovered.

This French statue from the 1100s, which is also a reliquary, shows Mary in a stiff, formal frontal pose. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

With the loss of Christian territory to the Muslim Seldjuks, Byzantine emperors appealed to Europe for aid, sparking the Crusades. Crusaders traveled the Holy Land and visited sites associated with the life of Christ and Mary, bringing back souvenirs and relics depicting Mary in eastern Christian styles. Replicas of the Holy Sepulchre were built all over Europe.

Byzantine icons influenced Marian art such as this Italian painting from the 1200s. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Thousands of statues, paintings and carvings were created, with eastern, western and regional traditions incorporated into them. In central and southern France, Iberia and parts of Italy, black Madonnas were made of dark wood or painted black. Many still exist, including one in my ancestors’ home village of Sablieres, France.

Defense of Mary’s purity became an inspiration behind massacres of Jews that swept the Rhineland in 1096. Mary, the symbol of the church, was shown as the correct sibling. The wrong sibling, the synagogue, was shown blindfolded and dejected, holding the spear and sponge of the Passion of Christ. Mary thus took on the unsavory taint of anti-Semitism.

Francis of Assisi (1181/2-1226) and other Franciscan monks worked in towns and cities in their simple woolen habits, assisting the parishes in offering religious education, sacraments and celebrations in vernacular languages. They made aids to personal prayer that gave Mary a central role. They made Christianity local and personal. At Christmas in 1123, Francis made a crib with the figures of Mary, Joseph, the baby Jesus, a donkey, ox and shepherds. He celebrated Christmas Eve mass with the scene. Greccio, Italy, became a recreated Bethlehem. Thus began Christmas nativity scenes that are today recreated all over the world. Franciscan churches all over Europe began to display humble nativity scenes. Franciscans also became custodians of Christian sites in the Holy Land. Bethlehem got its own nativity scene.

Franciscan monks took Mary out of monasteries and cathedrals into neighborhoods, making her a model of humble humanity and purity for urban wives and daughters as well as nuns. She became accessible in vernacular languages through art, poetry, drama and imagery aimed at making her the center of common people’s lives.

This German wooden set of statues from the 1300s depicts Mary and Elizabeth. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

By the mid-1300s, Mary was becoming more natural looking. She posed leaning and took on a more accessible expression. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Triptychs like this ivory one carved in Germany in the 1300s for individual worship brought Mary into people's private lives. This was one of many types of Marian objects that were used in private worship. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This 1300s painting by Griento de Aipo shows the typical golden background and touches of paintings of the era. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This 1300s painting by Griento de Aipo shows the typical golden background and touches of paintings of the era. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

After the Black death killed a third to a half of Europe’s population between 1347 and 1350, Mary became a part of funeral services.

Church and secular rulers were obsessed with anti-Semitism and Jews were expelled from large parts of Europe. They were shown positively in art depicting Biblical tales and miracle stories, but the synagogue was shown negatively. Gradually, the idea that Jews who participated in Christ’s death lacked understanding faded so that they were depicted as Mary’s evil-intentioned, cruel enemy. The Passion became an anti-Semitic drama between Mary and Jews. St. Vitus’ cathedral in Prague claimed to possess Mary’s bloodied veil which she wore to the Crucifixion. It was displayed in a mid-14th century ritual and Mary thereafter was shown wearing a veil stained by Christ’s blood.

Religious feasts, pilgrimages, rituals and writings were created around Mary in the 15th century. Many thought this was idolatry or blasphemy and it helped fuel a backlash of bitter wars in the next century as Protestants tried to contain Mary’s image within the constraints of the Bible accounts.

Mary was positioned as a unifying mediator between believers and God as Christianity spread globally with the discovery of America and European adventurism into Asia and Africa. Catholic missionaries accompanying the conquest of the Americas took Mary with them. Her story was translated into a host of new languages from Nahautl to Tagalog and her image morphed into the Indian Virgin of Guadalupe and Asian versions at the hands of local artisans. The Virgin of Guadalupe has become the most prominent symbol of both devotion for Mexican Catholics as well as a symbol of oppression and violence in the history of Christianity of the Americas.

The Virgin of Guadalupe.

Mary’s precedence became an overwhelming trend. Theology created a place for her in God’s great enterprise of saving mankind from sin and trials. Believers’ yearning for help and consolation and a glorious future in heaven came together in her. The number of images, manuscripts, and songs about her proliferated in many languages. Their variety is astounding and led to an association of her with creativity as she drove new forms of art by the world's greatest artists and folk artisans. She became a conduit for personal pondering in an era that explored individuality, self-understanding and expression of emotions.

Mary became a source of wisdom and consolation in monastries and cathedral schools. She structured the day of nuns, monks and lay people as she became part of daily liturgies. She inspired feeding the poor and extending peaceful overtures. Tales abound of her guiding artists' hands in making images of her after they gave alms to the poor. She healed people, appearing to them with medicines. The visions contained previously unknown details of her life that were added to accounts of her. Among them were her coronation in heaven, which became common subject of paintings. The idea developed that she was so pure that her own conception was immaculate and she had never sinned, so feasts of her immaculate conception were celebrated.

This painting of Mary by Francisco di Christofano emphasizes her youth and innocence. Mary rarely grew old in art. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Lavish prayer books with images of her and bejeweled reliquaries depicting her life proliferated. Dramas inspired by her were staged in churches, many with music. New ideas about her were expressed through Gregorian chants which spread through Europe and blended with local music to become the prevalent musical style of the liturgy. Religious reforms criticized the chants for sensuality.

Mary became ever more beautiful as she was both affected by and influenced contemporary ideals of female beauty. She had flawless skin and features, long flowing hair and a graceful body.

Mary became the ideal Renaissance woman, with flawless skin and a demure expression. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

There was an upsurge of interest in Joseph in the fifteenth century and he became an exemplary Christian father and husband.

Mary, Joseph and the Christ Child. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Mary spread into new liturgical plays and feasts for apostles. She emerged from the past into the present as she was seen as a symbol of maternal love in monasteries filled with men who had joined when they were young and as she became the key figure in stories of transgression and repentence with happy endings. The number of sites of her miracles and visions of her grew. Pilgrimage shrines arose around them, some of which supported large monasteries and local economies. Rich donors were shown at her feet in paintings. Mary was increasingly shown as equal to Christ.

Mary with donors in a painting. Devotees had spiritual experiences that brought Mary into their currrent lives. These became the basis for paintings such as this one. The Metropolitan of Art.

She was a model for good wives, who were to submit as Mary did to the Angel Gabriel. She wove, cooked food, did household chores and knitted while sitting on her throne. Her marriage was a model for couples, who were to have physical relations only for procreation.

Italian artist Luca Signorelli gave this painting to his daughter in the 1400s, possibly for the birth of a child. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Holy Family became a role model family that was industrious and virtuous. Mary and her mother Anne taught the Christ Child to read. Images of Mary were on daily use objects, reinforcing her constant presence in the home.

Mary's perfection was portrayed by superb Renaissance artists such as Francesco Francia in the 1400s.

This Spanish picture from the 1600s shows Mary, Christ, Joseph and her mother Anne with St. Catherine, who claimed to have had visions of Mary. It is by Jucepe de Ribera.

Calendars developed in which events in her life were commemorated. Aristocratic women used prayer books with her image and themes from her life to teach their children to read and pray. Women used a Marian guidebook to meditate at various times throughout the day and made dolls, embroidered images and paintings to express their feelings about Mary. The Ave Maria became a child’s first prayer, a dying person’s last and the basis of the rosary.

Mary was at the center of nuns' meditations. Visions of her became a vicarious way for them to experience the emotions of childbirth and motherhood as they gave birth to Christ in them. Monks, on the other hand, had visions of becoming Mary’s spouse, Joseph, or her friend, John the apostle. As scholars discussed Marian doctrines, she became seen as blessing students with wisdom and purity. She was the queen in great literary works such as Dante.

Symbolism became associated with her. Animals such as the elephant, associated with chastity, and the panther, which bore offspring just once, became symbols of her. So did fine flower fragrances and some fruits and vegetables, which were shown in paintings of her. She was placed in a garden paradise, compared to a rose, and shown reading and holding flowers. She and Eve were shown together in some garden scenes.

Mary became associated with animal, food and flower symbols and elaborate fashion. The apples and fly signify evil and the cucumber redemption in this Italian painting by Carlo Crivelli, from the 1400s.

Mary was known between 1400-1500 as the Queen and Reformer. Kingdoms, principalities, duchies and city states invoked her in support of their claims to the right to rule. Henry the VI of England had visions of Mary and wore a blue cloak like hers. He founded and dedicated educational institutions to her. He was widely believed to have worked miracles with Mary. The dukes of Burgundy created an order of knights infused with Marian themes and imagery. Their mothers and wives participated in devotion to her. The Burgundian court style was adopted by other courts, including famous tapestries with Mary themes such as her taming a unicorn. Plays told the Christian story with Mary often the focus. Some are still performed today. Plays staged Mary’s assumption to heaven on a wagon that had a working lift in a ceremony for Henry VII of England. Religious drama combined Biblical and apocryphal stories, miracle tales, visual imagery of Mary, music and her feast days.

This Spanish painting from the 1600s depicts a miraculous event in which Mary saved Spanish forces from destruction. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Ethiopian court was devoted to Mary and desseminated worship of her throughout the kingdom as part of unification efforts. The Ethiopian emperor and others had visions of Mary. Mary helped define dynastic and national identity for this Christian kingdom in Africa. Mary was used in diplomatic efforts between east and west and invoked in efforts to pacify conflicts in Europe. The Teutonic order, which conquered and converted northeast Europe, named its castles in Prussia and Livonia after Mary and founded churches with triumphant statues of her.

This Spanish statue from the 1400s shows the blending of local and universal styles in Marian art. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In the 14th century, a new image appeared, the Pieta, in which Mary lamented her son with his dead body limp in her lap. Mary was often depicted pierced by a sword.

This German alterpiece shows Mary mourning her dead son. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A German stained glass window from the 1500s depicts the multi-cultural influences on Mary through the Magi. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Mary was a rallying point for religious and political reform that called for suppression of Jews, witches, heretics, usurers and corrupt rulers. Mary was used to represent the reformers' agenda of chastity, family values, modest consumption and abolition of luxurious public displays. The reformers denounced fanciful stories of Mary. The reform movement offered Mary as a source of hope and alternative to sin, combined with enmity against Jews who were expelled from cities. Their vacated spaces sometimes became chapels for Mary or places for statues of her and the Christ Child. Mary was depicted with angels, and surrounded by golden rays separating her from others, emphasizing that she was of Heaven. She was a popular decoration on priestly garments, replacing the Crucifixion in some cases. The Trinity were reconfigured as three suitors wooing her. There were images of the Trinity in her womb, which some decried.

Reformers were deeply committed to the renewal of the Christian family and simple Christian lives. Martin Luther developed the theme of a simpler Mary as a simple housewife of perfect faith and obedience. It is this image that helped give rise to the Christmas of today, centered on the gathering of family at home.

By the end of the 16th century, Christian cultures had a magnified Catholic Mary, a more modest Biblical Mary, and eastern Christianity with ancient traditions about Mary. It is these traditions that still feed the aesthetics of today’s Christmas nativity scenes. Through them, Mary continues to fascinate millions of people today.

This version of Mary and the Christ Child by Francisco di Christofano is from the late 1600s. It shows an unadorned Mary and the Christ Child in a simple moment of sweet affection as the pendulum began to swing back toward Biblical depictions of Mary.

Related photos:

Check out these related items

Non-biblical Nativity Figures

Why are those figurines in large nativity scenes dressed in European dresses and broad-brimmed hats instead of Biblical costumes?

Wise Men Came Bearing Gifts

We all want to give during the holiday season. Here are some tips on how to give wisely and well.

Shortbread - Santa’s Favorite

Here's a Christmas secret - Santa prefers shortbread to sugar cookies. Here's a shortbread recipe to keep him happy and plump.

Salsa for the Holidays

Salsa is one of America's most loved foods. Here are some holiday fruit salsa recipes that are a nice change from tomato salsas.

Paris’s Oldest Church Restored

Paris' oldest church, Saint Germain des Prés, is emerging from layers of grime and soot as a meticulous restoration reveals its vibrant color.

The World Mourns Notre Dame

Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris, France's national cathedral, was badly damaged in a fire.