Paris’s Oldest Church Restored

Photos by Forrest Anderson

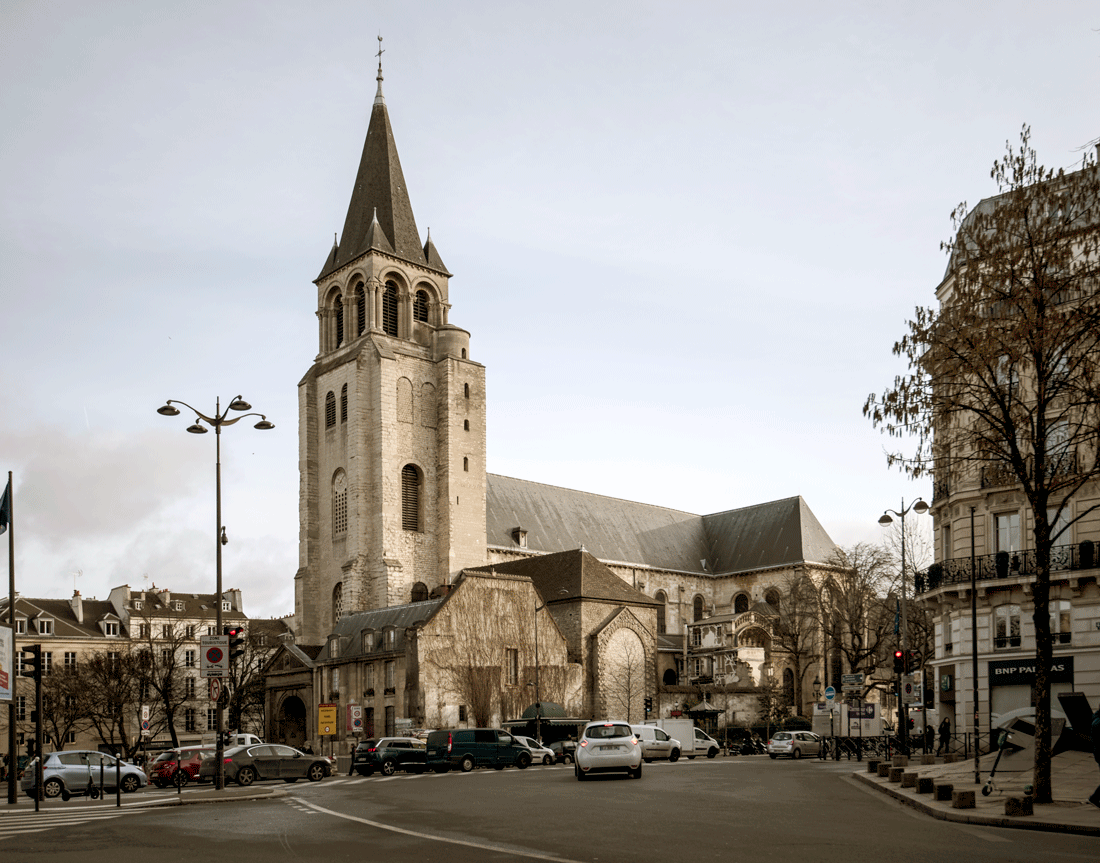

While efforts to save Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris have captured the international spotlight, the city’s oldest church has been gloriously emerging from under layers of black grime and soot.

The interior of Saint Germain de Prés Church on the Left Bank of the Seine is being painstakingly restored, its once-dark gloomy interior now a riot of saturated color from glistening stained glass windows, murals and colorful painted columns.

Before the restoration began in 2012, Saint Germain de Prés was among the many fixer-upper historic buildings that the city of Paris has the ominous task of restoring and maintaining. Coated with generations of dirt and candle smoke, its fine art collection and stained glass windows were deteriorating in excessive humidity caused by poor water drainage from the building’s facade. Some of its walls and fine medieval columns were crumbling.

Now, the majority of the church is awash in bright sparkling color from the newly cleaned murals, windows, decorative motifs and star-studded ceiling.

Various versions of the beloved church have risen over one of Paris’ most famous neighborhoods for more than 1,450 years, since the reigns of the early kings who sought to rule over the Franks. King Childebert, the son of King Clovis I, founded the church and its monastery in 543 to house holy relics and the tunic of the Christian martyr Saint Vincent of Saragossa, Spain. The original church’s first bishop was Germain d’Autun, and the church was named after him after he was sainted by the Catholic Church. He and all of the French kings until the late 8th century were buried at the church, although their remains have since been moved to the royal necropolis of Saint-Denis in Paris.

The church has had a rocky history. It was destroyed by Viking invaders in 875 and rebuilt with marble columns, paintings, mosaic floors and a copper roof that glowed in the sunlight. Norman aggressors looted and burned it again in the 10th century. Only a worn cornerstone and a marker for Saint Germain’s original tomb remain of the earlier church. A new Romanesque basilica on the site was completed in 1014, an event that was commemorated in a millennial celebration in 2014. The church’s bell tower from this construction phase is the oldest in the city.

In 1150, the church was remodeled in Gothic style, with arcades, three-tiered false loggias, arched windows and a rounded ambulatory that remain today. This configuration, then considered innovative, was adopted for other churches and became a model for early Gothic churches. The church had three towers, one of which remains, and flying buttresses before Notre Dame had them.

Unrestored sections of the church, scheduled to be tackled in 2021.

The abbey became a major intellectual center, with one of France’s largest and most important libraries that housed thousands of rare manuscripts hand-copied over centuries by monks. The first Bible printed in French was printed in the abbey.

The Virgin Mary Chapel, added in the 13th century, is considered a masterpiece. Changes also were made to the church in the 17th century and some of the artwork in it is from that period.

In 1792, during the French Revolution, the monks were expelled from the monastery, with any who resisted being executed. The church was repurposed as a refinery for saltpeter, an ingredient in gunpowder. An explosion caused by a fire in the factory destroyed almost everything in the monastery except for the church. By 1802, when the church was reopened for worship, it was in danger of collapsing. The city of Paris declared that the church couldn’t be salvaged, but parishioners and prominent people such as Victor Hugo sought to save it through a 30-year restoration effort that began in 1840 and resulted in the church that exists today.

Among the restoration efforts were a series of monumental murals on historical and religious themes done between 1842 and 1864 by artist Hippolyte Flandrin, who along with several decorative artists covered the interior with gold and multi-color artwork. The church’s murals, considered Flandrin’s masterpiece, were created in encaustic, or hot, wax in an attempt to reproduce ancient techniques found in archeological discoveries at temples in Italy and Greek colonies. The technique requires wax to be melted and then mixed with pigments and resins. Heat is applied to the surface of the painting to blend marks made by a brush or spatula so the painting’s finish is similar to that of an oil painting. It was a durable medium that has been relatively amenable to cleaning and restoration.

By the 2010s, the murals and decorative elements were so coated in dirt and smoke that they could hardly be seen. The graceful Gothic columns were in dire need of restoration.

Meticulous restoration and conservation of the church began in 2012, financed by a collaboration between the city of Paris, which is supervising it and contributing 15 percent of the funds, the Regional Directorate for Cultural Affairs and the Endowment Fund for the Protection of Saint-Germain-des-Prés Church. The project is part of a larger effort that including restoring some 20 monuments to protect and promote Paris’ religious and architectural heritage.

Funding for the church restoration also has come from parishioners; artists, galleries and collectors who donated artworks to be auctioned off to pay for the project; and a partnership between the French Preservation of Saint Germain des Prés Foundation and an American group called the American Friends for the Preservation of Saint Germain de Prés. Many Americans who have lived in or visited Paris have great affection for the Left Bank, which has been a popular place for them to congregate since it was where Benjamin Franklin, John Adams and John Jay signed the Treaty of Paris giving the United States independence from Britain.

The American organization is made up of former parishioners who now live in New York, history buffs, American soldiers who served in France, and tourists who have visited and loved the church. Some once lived in the Saint Germain des Prés neighborhood, which also includes the homes of writers, artists, publishing houses, museums, art galleries and universities and other cultural institutions. The French and American fundraising partnership has been successful enough that other Paris churches that are in need of funds for restoration have adopted it as a model.

Donors of means have provided funds for the restoration of sections of the church, while those with more modest resources have donated $100 each, receiving the right to name one of the more 3,000 stars that decorate the ceiling in memory of a person of their choice.

The problem with water not draining away from the church’s façade, causing excessive humidity that damaged artwork in the building, has been resolved. Leaks have been fixed and deteriorating stained glass windows have been repaired and restored. Restorers working on scaffolding have carefully removed dirt on the murals and walls with a mild soap, brushes, sponges and Q-tips, revealing the dazzling gilding, murals and wall decorations.

A restored section of the church with an unrestored section shows the grime that hid the vibrant colors and decoration.

The 5.7 million-euro project is expected to be finished in late 2021, but the main sections of the church are complete and it is possible to see it in its newly restored splendor because it is a working Catholic parish church that has remained open throughout the restoration. The church draws more than 600,000 visitors each year , making it a key Paris attraction. It also is common for about 1,000 local people to attend Sunday evening mass there. In recent years, mass attendance in Paris has increased and there is evidence of growing interest in religion in some parts of France, which has more than 32,000 churches, 6,000 chapels and 87 cathedrals.

The city of Paris, which owns city churches built before 1905 with the exception of cathedrals which are owned by the state, considers the restoration an arts and cultural project to preserve the historic church for future generations.

Flandrin’s 19th century murals depict both early French Kings and religious subjects - Saint Germain and other saints and religious figures as well as religious themes such as faith, hope, charity and patience. The church is a visual religious history. Adam and Eve, the Tower of Babel, Joseph sold into slavery in Egypt, Old Testament prophets, and Jonah and the whale share wall space with scenes from the life of Jesus Christ. Among the paintings is a 1677 one depicting the Resurrection of Lazarus that was among ones presented to Notre-Dame cathedral by the guild of goldsmiths. This piece was subsequently moved to the abbey of Saint Germain de Prés. The paint on this work was flaking and peeling, making it a top priority for conservation efforts. Another painting at the church was Christ’s Entrance to Jerusalem, painted in 1645. Others include a 1718 painting of the Baptism of the Eunuch and the Death of Sapphira which once were among ten scenes illustrating the Acts of the Apostles that adorned the church’s nave.

Because of its great age, the church also is a historical record of architectural styles from Romanesque to Gothic to 19th century classic revivalism to modern. Some of its stained glass windows are up to 1,000 years old and its stone carvings, mosaics and other artwork spans centuries. It is a leading example of both medieval architecture and 19th century decoration. One of its arches, for example, has capitals and bases from the early Gothic period, 19th century woodwork, a statue of Saint Rita from the 1930s and a stained glass window from the 1960s.

This unrestored section includes elements from the Gothic era to modern times.

When restoring a building that has been used for a long period of time, experts must decide what era to restore it to. Saint Germain de Pres is being restored to its late 19th century state. To some extent this has meant reversing a 1950s restoration that stripped part of the church down to the early Gothic period.

Paris’ Department for the Conservation of Religious and Secular Artworks is responsible for some 40,000 works in almost 100 religious buildings that belong to the city as well as about 750 statues in public places in the city. This requires a sophisticated interdisciplinary approach to restoration, The Saint Germain de Prés restoration has required the expertise of a number of government departments responsible for scientific and technical oversight of historical treasures. Among them is the Mural Painting Department of the Laboratory for Research on Historical Monuments. The restoration team includes a variety of restoration experts, an art historian who specializes in the 19th century, archeologists, masons, sculptors, carpenters, ironsmiths, experts in preserving complex artworks and master glassmakers to restore the stained glass windows. The restoration work has been led by Pierre-Antoine Gatier, an architect and specialist in restoring French historical monuments who has taken part in the restoration of numerous religious monuments dating from the Middle Ages, the Baroque period and the 19th century. There also has been an effort to have apprentices work on the project to pass traditional skills on to the next generation. The restoration process is difficult, painstaking and expensive.

The 19th-century furniture, 12th century sculpted capitals in the building depicting scenes from monastic life as well as plants and animals, the stained glass windows and columns and 17th-19th century paintings all are part of the restoration. The paintings’ frames must be cleaned and treated with insecticide and the paintings cleaned and restored. Discolored varnish has to be stripped away, patches of paint reattached and missing sections replaced.

The stained glass windows have had to be cleaned and some retrofitted to eliminate leaks and corrosion. Some are being protected with glass panels.

Among the restoration tasks was to deal with excess salts that accumulated in the church during past flooding and when the church was used as a saltpeter factory. Walls have had to be not only cleaned but desalinated.

Medieval parts of the church needed weakened parts and sections of plaster replaced. The restoration has required extensive documentation of materials and patterns and studies of stone used in the church’s construction. The project has aimed to conserve the surviving elements and replace damaged stones only when necessary. It has required cleaning medieval column capitals and returning them to their original positions, consolidating crumbling stucco with resin injections and reinforcing columns. Missing sections are being replaced with stucco marble reconstructions. The restoration has been an opportunity for experts to study medieval capitals, painting techniques and construction techniques used on the building.

The church’s statues, which date mainly from the 17th-19th centuries, have had to be cleaned of dirt and yellowing wax that was used to coat them and missing pieces of them have been replaced. A number of monumental statues, including a 1722 statue of Saint Francis-Xavier in a main altar, two 1683 statues and a 1705 statue of Saint Marguerite in a gilded altar have been part of the restoration.

The restored Saint Marguerite Altar.

The Church’s wooden furniture – sculptures, pews, doors and confessional – dates mostly from the 19th century. It had been damaged from humidity, dust and insect infestation. It needed structural repairs, stripping of varnish, cleaning and replacement of missing or damaged sections and paint and gilt work.

Check out these related items

What is the Louvre?

The former palace, the world's largest museum, music video and fashion show venue, and global brand has never been more cool.

The Many Layers of Mona Lisa

Mona Lisa has long been mysterious, not just because of her smile. But was mystery or realism her famous creator's object?

Marie Antoinette and Barbie

Since she was guillotined in the French Revolution, Marie Antoinette has become one of the most popular icons worldwide.

Paris’s Oldest Food Market

Rue Montorgueil in Paris began as a village street with a medieval church and food market. It has retained that character.

A Tale of Two Roman Cities

The amphitheaters, military garrisons, forums, trade and craft shops of two Roman colonial cities have emerged from the dust.

Enchanted Land, Part 1

A search for ancestral roots in southern France leads to a legendary land with a walled medieval town and tales of a magic sword.