Marie Antoinette and Barbie

Photos by Forrest Anderson, artwork by various artists

Every once upon a time, a famous and powerful woman captures and holds the public imagination not just of her own era but of successive generations, continuously reinvented in the popular imagination until it becomes almost impossible to sort out the facts of her life from fantasy. Among such women are Cleopatra, the Chinese Empress Dowager Cixi, and, of course, Marie Antoinette.

Few people have so captured long-standing public attention than has this queen of France who lost her head to the guillotine in the French Revolution. Depending on what side of the revolution people were on, Marie Antoinette in her time was either the reviled symbol of an incompetent, spendthrift monarchy that bankrupted France or a martyr to the ancient tradition of kingship.

Today, her political role in France’s epic human rights struggle receives less attention as she has been reinterpreted as a fashion icon, comic book figure and strong woman in a power struggle against male dominance.

Marie Antoinette was the Austrian-born youngest daughter of Frances I, the Holy Roman Emperor and thus had impeccable royal credentials that shaped her worldview. She was a poor student, but a good musician who played three instruments, had a beautiful voice and excelled at dancing. At age 14, she was married off to Louis-Auguste, the heir apparent to the French throne, in a dubious alliance intended to patch up relations between the two oft-warring nations to combat the ambitions of Prussia and Great Britain. Four years later, her husband ascended the throne as Louis XVI and she became France’s queen. He was just 19 and she 18.

The French reaction to her at first was mixed. Commoners liked the beautiful, personable and poised young queen, but those who opposed alliance with Austria disliked her.

France was in severe financial straits as a result of expensive wars and the crushing cost of the royal court. Riots caused by the high price of flour and bread broke out. There is no evidence that Marie Antoinette ever uttered the phrase for which she is famous, “Let them eat cake,” when told that the starving masses had no bread. This phrase apparently was uttered by another princess long before Marie Antoinette went to France.

Nonetheless, the sentiment of the quote reflects Marie Antoinette’s tone deaf approach to the crisis. It is ironic that she is used today in so many advertising campaigns, as she was a public relations disaster of monumental proportions.

As the French people starved, Marie Antoinette renovated a private chateau at Versailles that her husband gave her, spent heavily on elaborate fashions and wore the pouf hairstyles up to three feet tall and feather plumes which have come to define her style. She was so oblivious to the French people’s misery that her mother wrote to her repeatedly expressing concern about her decadent spending and the civil unrest caused by it.

Marie Antoinette and her family lived in luxury in several palaces as the French financial angst deepened. This is her salon at the Louvre. Below, the golden splendor of Versailles.

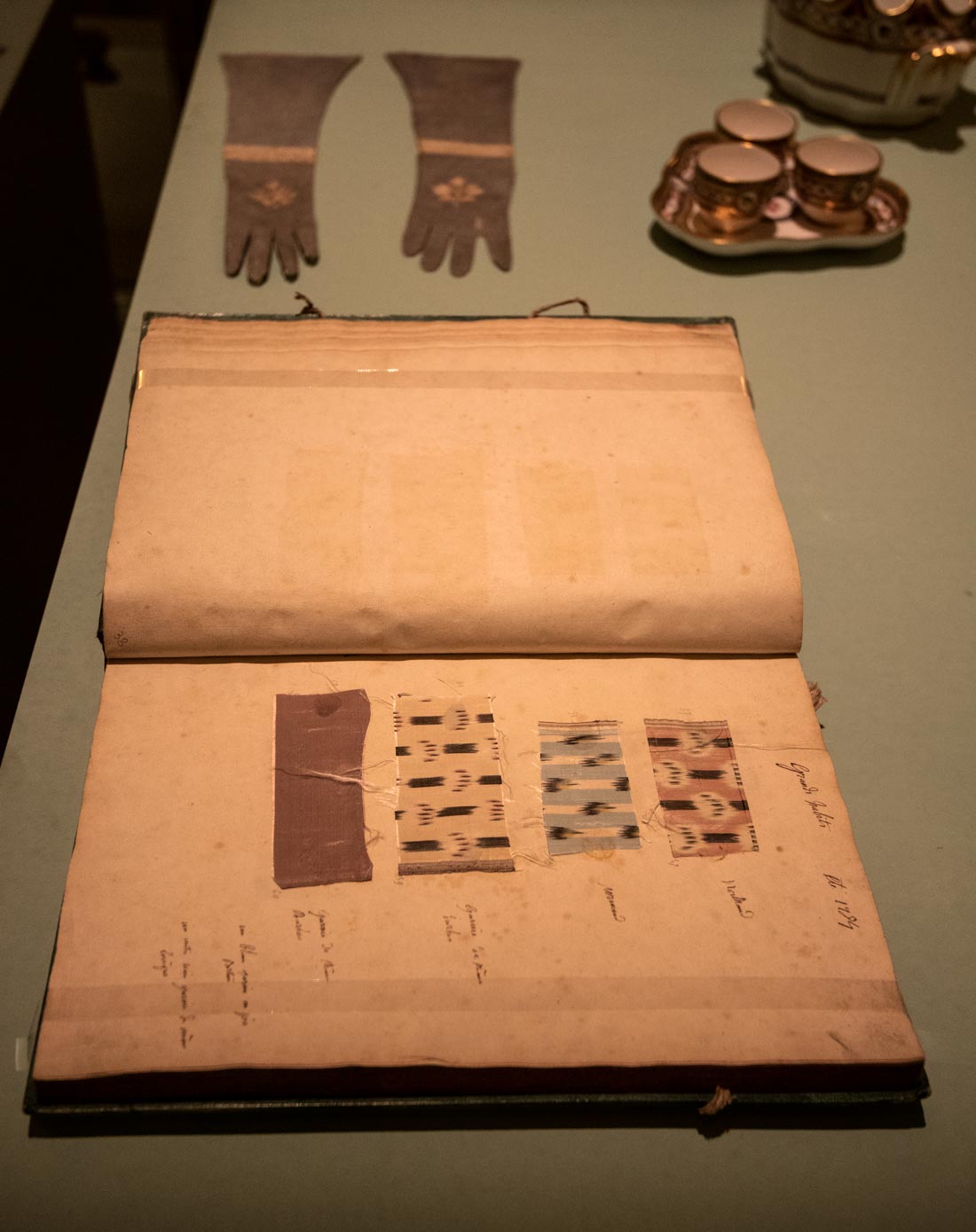

An account book with swatches from materials from which Marie-Antoinette's luxurious wardrobe was made. This and other artifacts shown in the photos in this blog were part of a recent exhibit about her life at the Conciergie in Paris. They are from a variety of museums, and historical sites and the French National Archives.

She loved the theater, and insisted that The Marriage of Figaro be shown in Paris despite its negative portrayal of the aristrocracy. The play helped turn public opinion against the monarchy.

Political pamphlets accused her of being promiscuous, not a surprising charge given the licentious environment of the 18th century French court. Her clothes were a source of contention even when she abandoned the heavy makeup and wide side hoops of the court in favor of a simpler look, as the older generations thought her new look improperly casual for a queen.

In an attempt to rehabilitate her image, she tried to portray herself as a loving mother in paintings of her with her children.

Someone who looked like Marie Antoinette impersonated her in purchasing an expensive diamond necklace that the queen had refused to buy because she said the nation needed ships more. She was not to blame in the scandal that followed, but it still badly damaged her reputation and that of the monarchy. She came to be called Madame Deficit.

Marie Antoinette got Austrian and Russian support for France’s involvement in the American Revolution and supported French officials who helped the Americans defeat the British. As if the domestic woes weren’t enough to turn people against her, she also was accused of favoring her native Austria over France in a series of diplomatic decisions. As France’s situation deteriorated, the king descended into a deep depression and he turned to his wife more for support and help. Her attempts to rectify the situation did little more than result in her being blamed for their failures. She influenced the appointment of powerful ministers who rejected changes in the government structure. She helped block commoner access to important military positions, challenging the concept of equality that became a main battle cry of the French Revolution. The aristocracy and clergy were unwilling to relinquish some financial privileges to help the situation and Marie Antoinette opposed major financial reforms. Her own secret expenses made the cost of the court much higher than the official estimates. She urged her husband not to concede to popular demands for reform and to use force to crush the revolution.

Louis XVI’s and Marie Antoinette’s son, the heir to the throne, died in 1789 as the French Revolution gathered steam. The aristocracy began to leave France as riots in July 1789 culminated in the storming of the Bastille. The National Constituent Assembly and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, drafted by Lafayette with Thomas Jefferson’s help, stripped away the king’s power.

Amid critical bread shortages, a Paris crowd descended on the royal palace of Versailles and forced the royal family to move to the Tuileries Palace in Paris, where they lived under house arrest. They were guarded by Lafayette’s National Guards. Lafayette, who had been a military leader in the American Revolutionary War and advocated a liberal British-style constitutional monarchy, detested Marie Antoinette and she loathed him in return.

Marie Antoinette, her husband and other family members tried unsuccessfully to escape from Paris during the night on June 20-21, 1791, to initiate a counter-revolution. Her unwillingness to support the moderate advocates of a constitutional monarchy is considered a significant factor in their loss of power to a more radical faction. At her insistence, Louis XVI vetoed measures that would have limited his power. She hoped that a military coalition of European kingdoms would quash the revolution. However, France declared war on Austria because of the Austrian monarches’ strong support for Marie Antoinette. This led to her being considered an enemy of France. The situation was made worse when the Austrians defeated the French armies in battles partly because she passed military secrets to the Austrians.

The moderate government collapsed in April 1792 and Marie Antoinette refused to collaborate with the new majority that controlled the legislative assembly. A mob broke into the Tuileries palace and imprisoned the royal family. The monarchy was abolished a little over a month later in September. Louix XVI was tried and executed on January 21, 1793. Marie Antoinette was not tried until Oct. 14, 1793 because the government couldn’t decide whether to exchange her to the Austrians for French prisoners of war or for a ransom, exile her (Thomas Paine suggested America), or execute her.

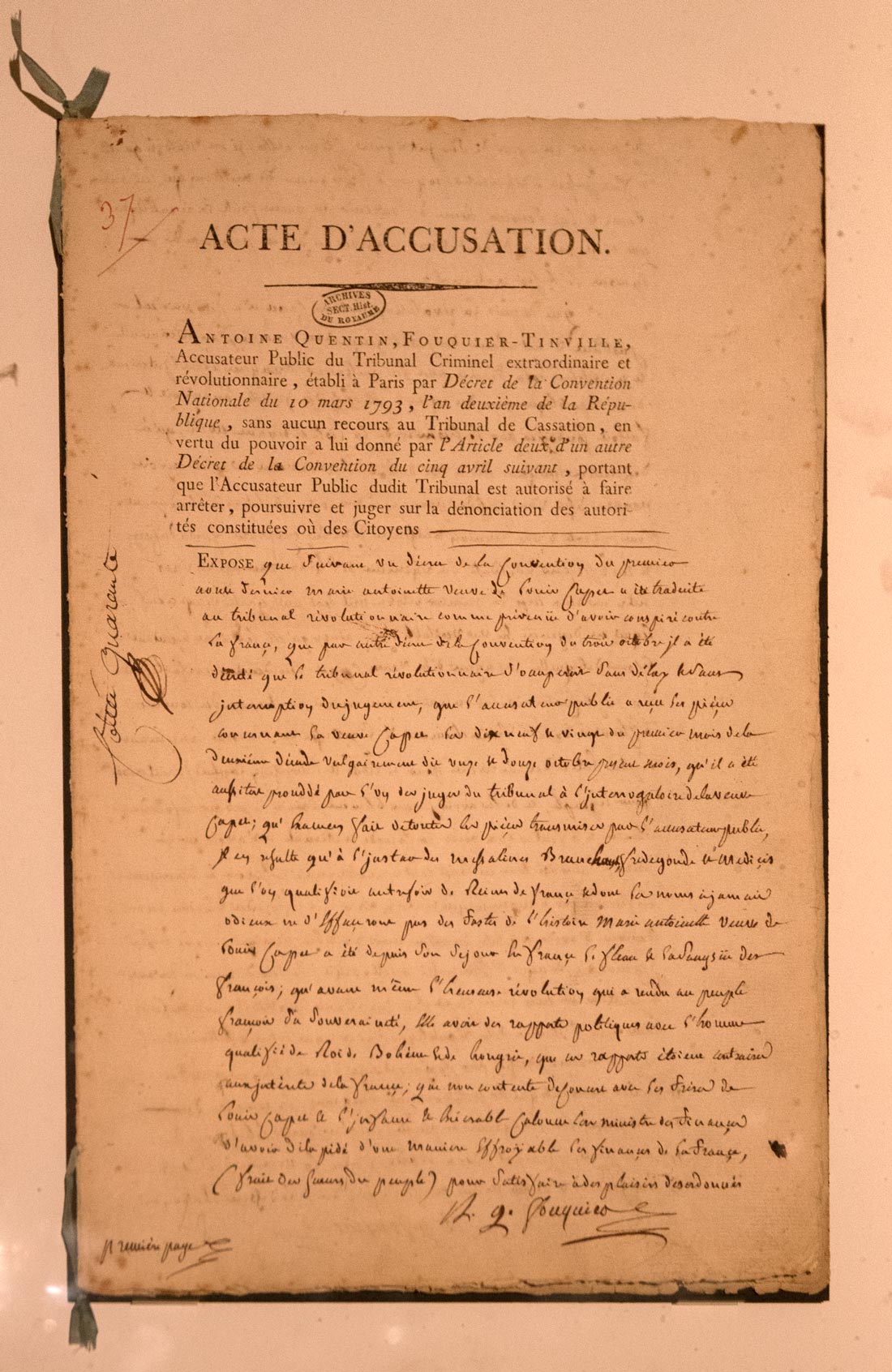

The official accusation against Marie Antoinette.

In the fall of 1793, she was transferred to an isolated cell in the Conciergerie in Paris and placed under constant surveillance.

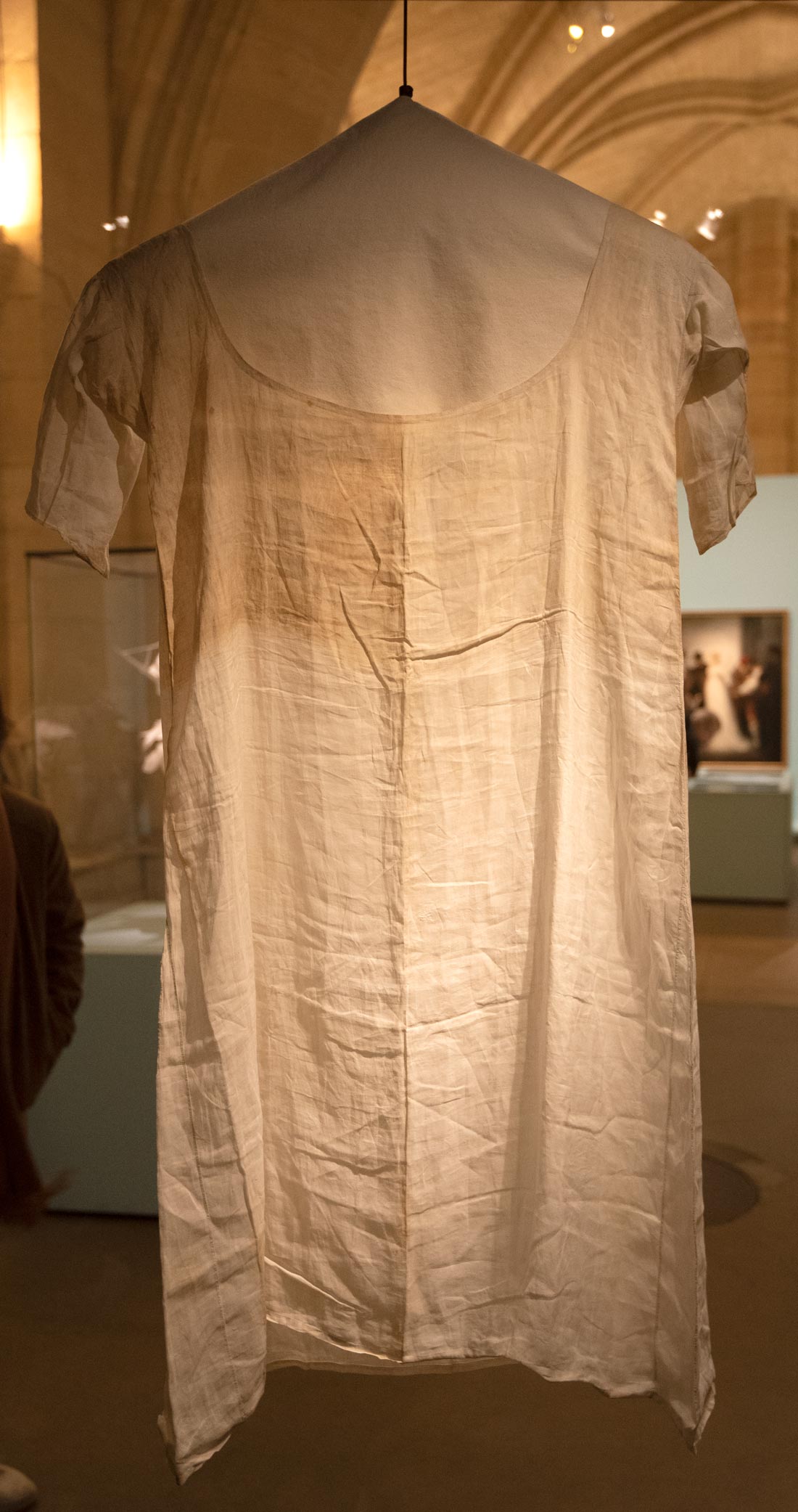

A blouse Marie Antoinette wore while in the Conciergerie.

Her trial took just two days. She was convicted of depleting the national treasury, conspiracy against the security of the state, and high treason. In her final hours, she wrote a long letter to her sister-in-law, Madame Elizabeth. The letter, which was confiscated and never delivered to Elizabeth, was seeped in Marie Antoinette's royalist world view.

She spoke of going to rejoin her husband and hoping to show the same firmness that he did in his last moments. She said her mind was tranquil because she was guiltless. She expressed great grief that she had to leave her living children and worry about their welfare (they later died, one at the hands of the revolutionaries and one in prison of illness).

“Let them both reflect on what I have unceasingly taught them, that virtuous principles and the exact performance of every duty are the first basis of life; that their happiness will depend on their mutual affection and confidence…. how much consolation in our misfortunes has our affection afforded us! And, in prosperity, happiness is doubled when shared with a friend; and where can one find a friend more tender, more dear, than in the bosom of one’s own family? Let my son never forget the last words of his father, which I emphatically repeat to him —

“Let him never seek to revenge our death.”

“I die in the Roman Catholic and Apostolic Religion, that of my fathers, that in which I was educated, and which I have always professed," she wrote. She asked pardon of God for her faults and hoped he would receive her soul in mercy and kindness. "I ask forgiveness of all with whom I am acquainted, and of you, sister, in particular, for all the pain, which, without intending it, I may have caused you. I forgive all my enemies the injury they have done me. I here bid adieu to my aunts, and to all my brothers and sisters. I had friends! The idea of being separated from them forever, and of their afflictions, is the greatest grief I feel in dying; let them know at least, that to my latest moment, I thought of them.

“Adieu, my kind and tender sister; may this letter reach you. Always think of me; I embrace you with my whole heart, as well as those poor and dear children: O my God! how heart-rending it is to leave them for ever! Adieu! Adieu!”

She ended by saying that if the revolutionaries brought her a priest, “I here protest that I will have nothing to say to him, and that I will treat him as a perfect stranger.”

Marie Antoinette dressed in a plain white dress in the presence of her guards for her execution.

Wiliam Hamilton's famous painting of Marie Antoinette being led out of the Conciergerie for her execution.

Her hair was cut, her hands tied behind her back and a rope leash was tied on her. She was taken to her execution in an open cart, sitting next to a constitutional priest who was assigned to hear her final confession. She ignored him as she had vowed in her letter she would do.

Attendees of the exhibition at the Conciergerie viewing a painting of Marie Antoinette being taken to her execution.

As she was to be executed, she accidently trod on the foot of the executioner. Her last recorded words were, “Pardon me, sir, I did not do it on purpose.” She was then guillotined and her head held aloft to the crowd, which shouted, “Viva la republique!”

This engraving of the time depicts Marie Antoinette's head being held aloft after she was guilletined

The event was a brutal national catharsis for France and became a symbol of the extremism of the French Revolution as France made its long bloody journey toward being a republic. One of the reasons the event was so traumatic for the French people was that the majority of the country and the royal family were Catholics. Many believed in France’s ancient tradition of the divine right of kings. The sense that France was being punished by God for the excesses and secularism of the French Revolution and its aftermath, including killing the king and queen, persisted for well over a century as a force in French politics.

After Marie Antoinette’s death, Marie Tassaud made a death mask of her head. Her body was tossed into an unmarked grave in the neaby Madeleine cemetery.

Many people, especially among the clergy and aristocracy, privately mourned her and the death of the monarchy. A mourning cult arose around her that was expressed in oblique references to the monarchy.

This porcelain plate contains oblique references to the slain royal family. Careful perusal of it reveals that the profiles of the dead king and queen make up the lower edges of the mourning vace shown. Such items were held by many aristocratic families who were horrified at the slaying of the king and queen.

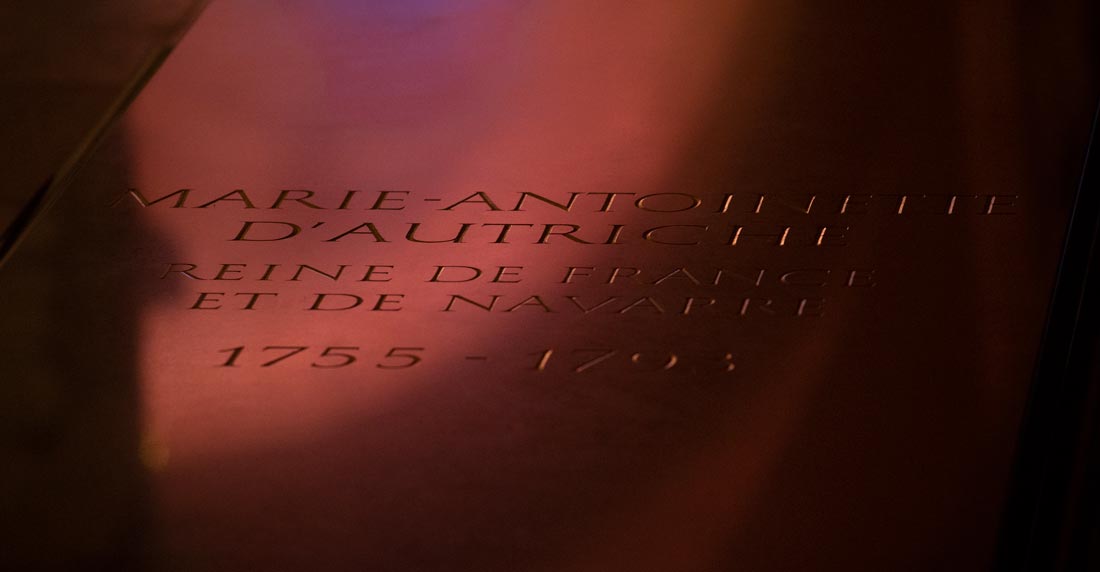

When the monarchy was reestablished in 1815, Marie Antoinette and her husband were posthumously rehabilitated. The little that was left of their bodies was exhumed and reinterred in a Christian state funeral in the necropolis of French kings at the Basilica of St. Denis in Paris. The Conciergerie became a place where people could go to reflect and to visit the dead queen's cell. An expiatory chapel was built on the grounds of the former Madelaine cemetery. Locks of her hair, always the most prominent symbol of her, were placed in reliquaries as part of the cult of mourning the monarchy.

Statues of the king and queen at Saint Denis and below in the basilica's crypt, the graves of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette are the two central ones. The next photo shows the inscription on Marie Antoinette's grave.

Since then, popular interest in her has continued unabated, with each generation reinterpreting her anew. She has been depicted in famous historic paintings, widely circulated engravings, school textbooks and wax museums.

Later queens of France modeled themselves after her and they and their supporters viewed her as a martyr, while opponents of the monarchy depicted her as a decadent traitor. She has been alternatively a saintly martyr and a sinner, mother and monster, princess and wicked queen in the public imagination. During the Second Empire, the Empress Eugenie, wife of Napoleon III, liked to wear clothes similar to those of Marie Antoinette, and revived the dead queen’s style. Eugenie organized an 1867 exhibition in honor of Marie Antoinette. People hostile to the French Revolution revived traces of Marie Antoinette at her chateau at Versailles.

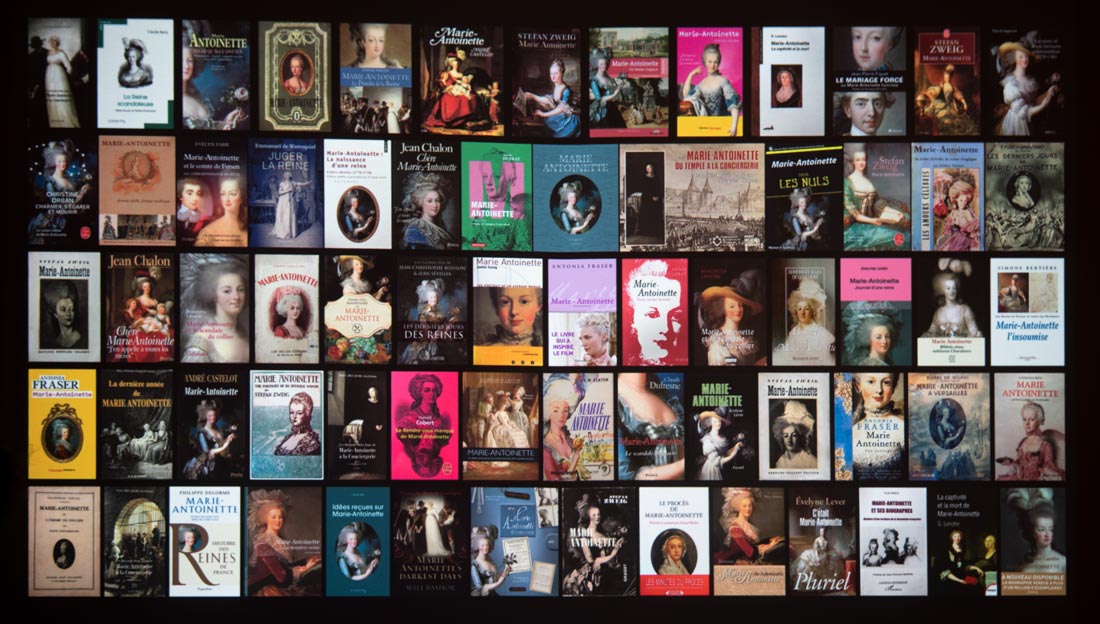

Through it all, she has been depicted as a fashion icon that has in modern times gone global. She is one of the most represented historic figures in contemporary art, film and fashion. Dolls are dressed like her, cartoon figures portray her, she is the theme of advertisements. She helps sell luxury products from candles, bath salts and beauty products to stationery and chocolate. Dozens of books have been written about this public celebrity who sparked curiosity by insisting on a private life.

Dozens of books have been written about her.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, she has appeared in about 100 films, depicted by a variety of stars. Miss Piggy portrayed her in a well known episode of the Muppets in which the Bee Gees’ song “Stayin’ Alive” was sung.

Costumes for films about Marie Antoinette.

Miss Piggy as Marie Antoinette and below, Barbie as the queen.

The huge wigs her hairdresser created for her have been revived in modern fashion, the arts and advertising.

A modern painting of Marie Antoinette by Kimiko Yoshida.

Gallows humor such as the salt and pepper shakers below abound in depictions of Marie Antoinette's execution.

In the past 20 years, she has been reinterpreted as a symbol of an abused woman who tried to shape her life independent of male power. She has become a global icon of a modern young woman. This despite her recorded gratitude to her parents for arranging for her a marriage to a stranger.

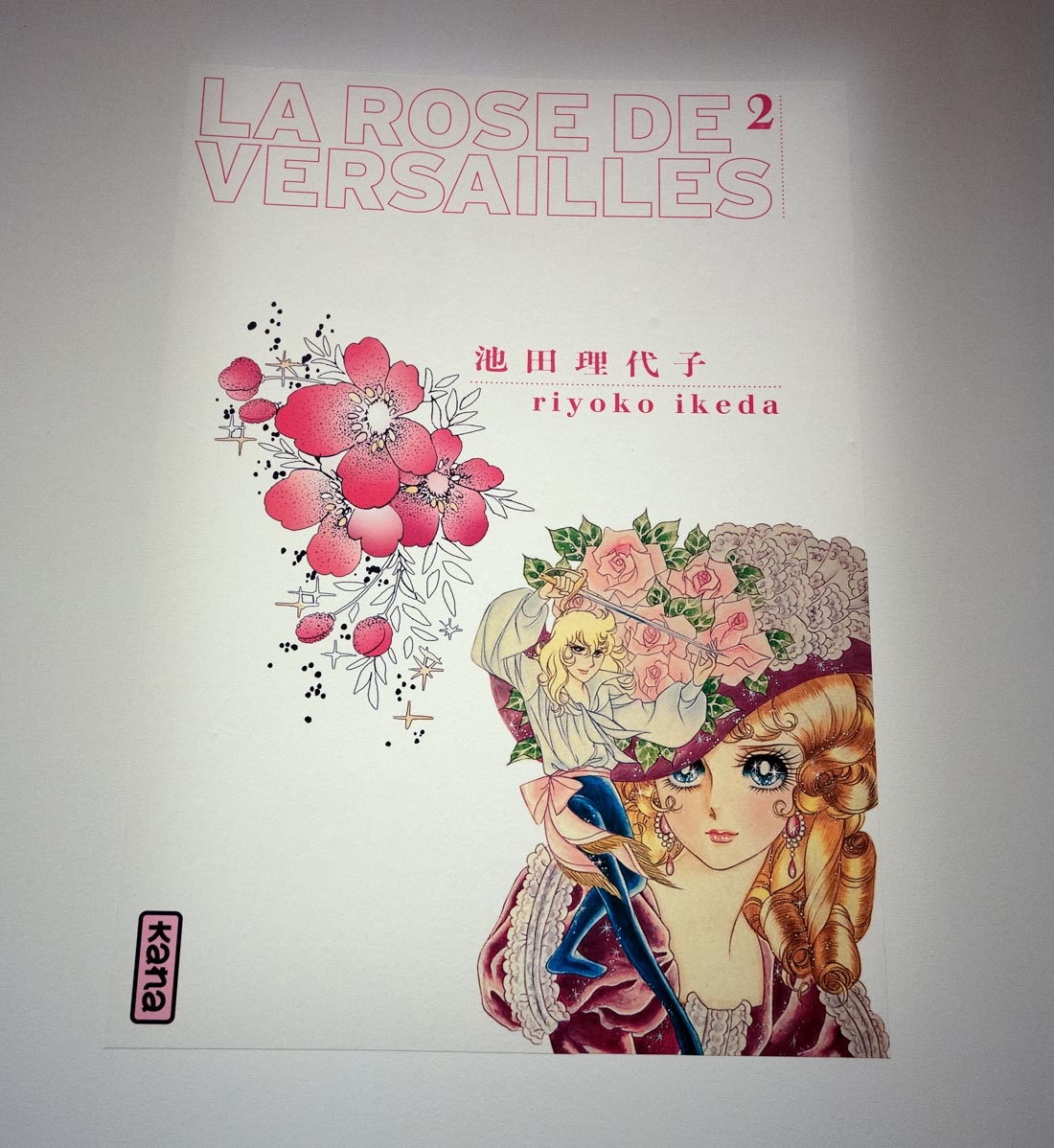

A Japanese manga comic book series, The Rose of Versailles, helped her achieve popularity. Its 82 episodes were published worldwide in many languages.

She is regularly invoked on fashion runways with models wearing Marie Antoinette-style costumes. Madonna and Rihanna have drawn upon her for performances. She is a perennial theme in pop art. She is used to sell furniture, shoes, cakes, dishes, paintings, and anything that draws on the exuberant, elaborate French style of the late 18th century that has become one of the world’s most iconic visual styles.

Marie Antoinette-inspired fashion by Christian Dior and below, couture shoes.

Marie Antoinette-themed chocolate and other items.

As Marie Antoinette once was credited with having said, “There is nothing new except what has been forgotten.”

Check out these related items

Paris’s Oldest Church Restored

Paris' oldest church, Saint Germain des Prés, is emerging from layers of grime and soot as a meticulous restoration reveals its vibrant color.

Scaffolding the World

Finding a historical site shrouded in scaffolding is disappointing, but it is a valuable tool for preserving the world's heritage.

What is the Louvre?

The former palace, the world's largest museum, music video and fashion show venue, and global brand has never been more cool.

The World Mourns Notre Dame

Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris, France's national cathedral, was badly damaged in a fire.

Paris’s Oldest Food Market

Rue Montorgueil in Paris began as a village street with a medieval church and food market. It has retained that character.

A Tale of Two Roman Cities

The amphitheaters, military garrisons, forums, trade and craft shops of two Roman colonial cities have emerged from the dust.