Tracking Dinosaurs in the Wild

Photos by Forrest Anderson

When I stop to fill in the pages of my field book with the day's observations, I like to sit on the rim of one of the biggest tracks, a footprint a yard wide. The lime mud pushed up by the thrust of the hindpaw looks fresh even though it has been frozen in stone for a million centuries.

— American paleontologist Robert T. Bakker

When stymied by a pandemic surge and scrambled airline flights that limit winter adventure options, there’s just one conclusion to be reached. It’s time to track dinosaurs in the wild.

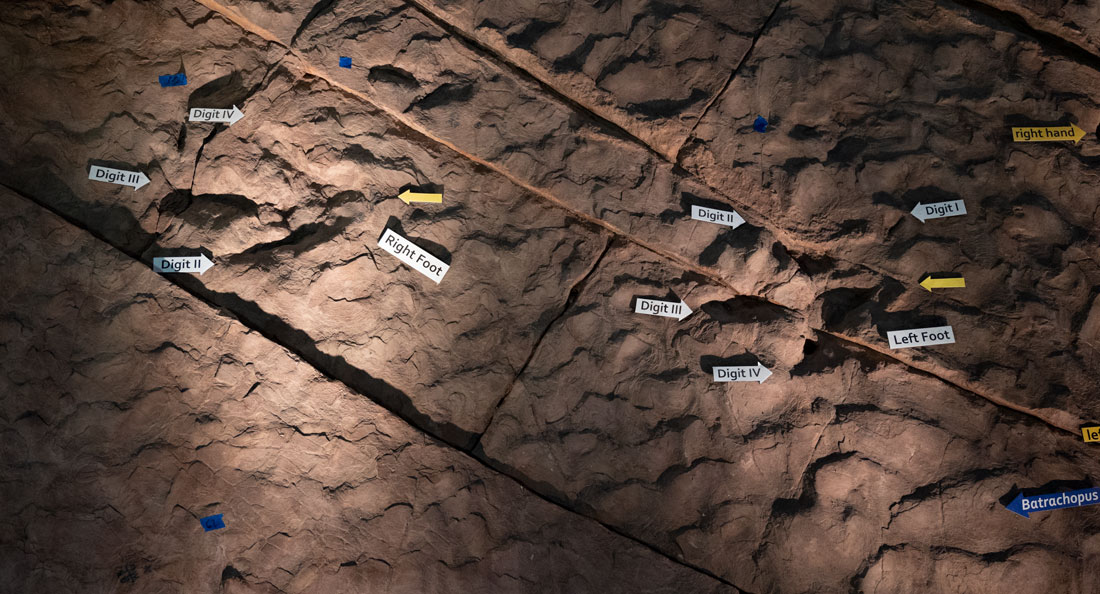

Tracks at Mill Canyon Dinosaur Tracksite, near Moab, Utah.

I fortunately live in Utah which is one of the premier places to find dinosaur tracks, but such tracks can be found all over the world because the planet was once covered with dinosaurs of all sizes and descriptions.

Numerous dinosaur track sites can be visited in a number of states in the United States - Texas, New Mexico, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Colorado, Wyoming and Alaska to name a few

Among countries with well-known dinosaur tracksites are Poland, Germany, Wales in the UK, Israel, China, South Korea, Germany, Australia (which has a 5.5-foot-long dinosaur track made by an immense animal), Bolivia (which has the largest single collection of dinosaur tracks – 5000 – on a vertical wall), Scotland (which has the tracks of an adult dinosaur followed by several juveniles), and Spain, where tracks of sprinting dinosaurs have been found.

Dinosaur tracks, unlike dinosaur bones, are not the physical remains of actual dinosaurs. They are simply remaining traces of dinosaur activity. Fossilized dinosaur tracks originally were created on what were beaches or low-tide mudflats where dinosaurs walked and left hundreds of footprints. The footprints were preserved through a fortuitous sequence of natural processes.

In some cases, the footprints are an indent where an animal stepped. In others, an animal stepped in mud and left a footprint that was later filled in by sediment, creating a rough cast of the animal’s foot.

Most dinosaur tracks probably never became fossils but were washed away by tides and rain or crumbled under the weight of sediments washing over them. Millions of footprints that were preserved probably are buried under younger layers of rock and sediment that piled on top of them over eons.

A small minority of these tracks have been revealed to view by water receding or tectonic action that pushed them up as mountains and cliffs formed. Others have been discoved during construction excavation and mining. Some of these tracks are now on sheer vertical cliffs or slabs that were uplifted and turned into vertical walls by tectonic movement.

Dinosaur track sites are important to the study of dinosaurs, because they can reveal things that dinosaur bones can’t. It is not uncommon for a type of dinosaur to reveal itself first with a footprint, and there are known footprints of species for which dinosaur bones have not yet been discovered.

Dinosaur tracks are trace fossils, the most spectacular subset of a branch of science called ichnology that studies the fossil record of biological activity rather than the preserved remains of animals and plants. Trace fossils are best preserved in sandstone. Only in very rare cases can scientists link the makers of trace fossils with their remains. Trace fossils are important in understanding creatures’ behavior - whether they used their front limbs to walk, their speed and their weight as well as water depths and the salinity of water. Some trace fossils can be used to date the rocks in which they are found. Tracks help paleontologists understand the approximate size of the animal, the direction it was heading, information and other observations about its daily life that we can’t learn from bones alone. They help scientists know whether their legs were under their body or off to the side, whether they walked on two legs or four and whether they dragged their tails.

Taken as a group, trace fossils can help scientists understand changes in environments and the environmental factors involved in mass extinctions. Our earliest evidence of animal life on land comes from trace fossils.

Dinosaur bones are the remains of animals that died and then fossilized, so in most cases, it is difficult to understand their behavior when they were alive. However, dinosaur tracks record behavior of living animals.

Researchers use dinosaur trackways to gauge the speed and mechanics of dinosaurs’ movements. They use a formula based on an animal’s stride length and hip height, which is estimated by quadrupling the length of a footprint. This type of studies have enabled scientists to estimate the sprinting speed of one theropod as up to 31 miles an hour using its tracks found in Utah. Tracks of running dinoslaurs are relatively rare because the muddy terrain that enables the creation and preservation of footprints isn’t the best running ground. This information is a valuable complement to calculations of running speeds used based on what fossilized bones reveal about an animal’s musculoskeletal system and size.

Here are some of the best and most accessible places to find dinosaur tracks in Utah at this time of year. In the winter, there are relatively few visitors to them so they are safe to visit during the pandemic.

Johnson Farm Dinosaur Discovery Site, St. George, Utah

This may be the greatest dinosaur track site in the world. In 2000, retired optometrist Dr. Sheldon Johnson was leveling a sandy hill on his property on the outskirts of the desert town of St. George, Utah. He was moving a large sandstone block when he discovered the casts of dinosaur tracks on it. He turned over other rocks and found dinosaur tracks on them.

Johnson realized the tracks’ scientific importance and contacted paleontologists who told him he had discovered the largest set of dinosaur tracks ever found.

Unlike many tracks that have long been exposed to the weather, the ones on the Johnson farm are clear and detailed, with some showing skin patterns on the feet of the animals that made them. To protect the tracks from weathering, the city of St. George bought the land they are on and built a museum over it.

Visitors to the museum can see huge natural casts of three-toed dinosaur feet that are 13-18 inches long.

Skin impressions on a track.

A dinosaur track and filled-in cracks in the mud.

During the early Jurassic period 200 million years ago, southern Utah and Arizona were close to sea level. The many streams and lakes in the area created the habitat for carnivorous Eubrontes dinosaurs such as the Dilophosaurus. This was the largest dinosaur of the early Jurassic period - 19 feet long, 6 1/2 feet tall and weighing about 900 pounds, with crests on the sides of its head. It stood on two legs and had huge three-toed clawed feet that made tracks that can be seen at the museum. A dew claw protruded from the back of the foot and traces of it can be seen in some of the tracks.

Tracks at the site range from huge ones to 4-8 inch ones made by slender meat eating Megapnosauruses and tiny one-inch Batrachopuses. The site also has swimming tracks, traces of dinosaurs having dragged their tails and fossils of fish and other ancient animals and plants, including conifers with the needles still attached. Among them are the bones of Coelacanth, a prehistoric 5-foot-long fish that had been thought to be extinct but has been found living off the coast of Africa.

A dinosaur model placed on footprints on the track site to show how the animals walked through the site.

Paleontologists at the site track trace and label tracks at the site to study dinosaur behavior.

The Johnson farm dinosaur tracks are part of what is called the Moenave formation of layered sandstone, mudstone and shale. The majority of the tracks were at the bottom of a three-foot thick layer of sandstone that was over mudstone. Paleontoligists have determined that the farm was once along a shallow, saline lake that covered hundreds of miles. The water receded, and dinosaurs walking through the clay left footprints. The mud hardened and the lake level later rose. The tracks eventually became buried by sand and silt which hardened and became sandstone in which the tracks were preserved.

These stones are like a book - When they were split apart, there appeared track impressions on one side that mirror the filled-in casts from sediments that show up on the other side.

In 2004, clear imprints of the heel, pelvis, tail, and shuffling feet of a dinosaur were excavated at the site - the first evidence of a squatting dinosaur. The discovery shows that the animal rested on its hind end and put its hands down with its claws curled inward, showing how dinosaurs held their hands. The dinosaur then moved forward before getting up and walking away dragging its tail.

Dinosaur tracksites near Moab, southeastern Utah

There are a number of dinosaur tracksites in the Moab area that have well-marked trails and interpretive signs. Some of these sites have many tracks and others have only a few. Here are the most accessible:

Mill Canyon Dinosaur Tracksite, near Moab, Utah

This tracksite is one of the largest and most diverse Early Cretaceous-period (112 million years ago) track sites in North America and one of the most significant in the world. It contains more than 200 individual tracks, including those of long-necked herbivorous dinosaurs, several types of carnivorous dinosaurs and crocodiles. It is part of what is called the Cedar Mountain Formation of sandstone and mudstone. Dinosaurs and other creatures walked through limey mud on the shoreline of a large lake bed with water sourced from a large river.

The trail is ¼ mile in length and has marked paths and boardwalks that form a loop around the tracksite, which visitors are not allowed to walk on.

Here are some of the highlights:

A slide mark that may have been made by an ancient crocodile sliding on its belly into shallow water. The animal left at least one footprint and possibly belly and tail slide marks in the mud. Crocodiles were relatively common in the later Jurassic through the later Cretaceous periods.

Dromaeosaur Tracks – These tracks are the first dromaeosaur tracks found in North America, although the animal’s tracks had earlier been found in South Korea and China. The tracks were made by a dromaeosaurid theropod that was probably a large Deinonychus. Only two toes are preserved in each track because the inner toe on each foot had a huge sickle claw that was held up off the ground as the animal walked. The tracks are almost 8.7 inches long and indicate an animal just under 4 feet tall at the hip. Unfortunately, a track was permanently damaged by an illegal attempt to make a mold of it.

Medium Size Theropod Tracks – These tracks are about 7-14 inches long. They may have been made by mid-sized theropods like Ornithominids.

Algae – One of the surprising features of this tracksite is that the ground is pale green. It was once a living mat of algae that formed in a shallow lake. The animals left tracks in the algae after the lake water receded but before the algae dried up. The mat was then buried by layers of sand and mud. It hardened and became limestone. The texture of the rock surface preserves the remains of the algae.

Ornithopod Tracks – The ornithopod tracks were probably made by iguanodon - herbivorous dinosaurs that could walk on two feet but also had the ability to use their front feet for walking. The tracks have a stride length of 43.45 inches and are about 11 inches long and wide. No skeletal remains of these dinosaurs have been found in the area, but similar dinosaurs have been found in slightly younger and older rocks.

Sauropod tracks – The lima bean-shaped front footprints of these long-necked, four-legged herbivores are slightly smaller than their back footprints. The front footprints are 8-9 inches long and the back ones are dinner plate-shaped and 13-19 inches long. You can see the toes on the side of a few of the hind footprints. In one case, a sauropod walked through the site after a large theropod and left its footprints over the theropod’s, overprinting it.

Large theropod tracks – These are the start of a 17-step trackway of a very large carnivorous dinosaur. The tracks are about 16-20 inches long and from a dinosaur at least 8 feet tall at the hip. No skeletal evidence of this animal has yet been found.

Sauropods or Ankylosaurs – The site has the tracks of an 11-foot-long four-legged dinosaur walking away toward the hillside. Paleontologists have determined that these tracks don’t continue into the hillside. The feet are rotated outward, resembling the feet of a sauropod tracksite in Spain. The handprints of the animal include finger impressions, which generally are not found in sauropod tracks. Some paleontologists think the tracks resemble those of known ankylosaurs – heavily armored dinosaurs – that were common in the area in the Early Cretaceous period.

This site is unique because it is of a different age and environmental setting than nearby Jurassic Period sites. It also has dinosaur, crocodile and bird tracks that are new to North America or from animals not currently known from skeletal fossils. Dinosaur dung with pieces of leaves in it was found on the track layer, indicating that land plants grew near the lake. The tracks and traces show that a diverse array of dinosaurs, reptiles, mammals and birds visited the site.

State-of-the-art photogrammetry using more than a thousand photos taken at the site has been used to create a detailed 3-D reconstruction of the site’s surface and an image map of it without touching the fossils. The imagery has been used to distinguish trackways that are hard to follow on the ground and to make depth maps of the tracks.

Dinosaur Stomping Ground, near Moab, Utah

The 1½-mile hike to this dinosaur tracksite is about 23 miles north of Moab, Utah. After a short drive from the highway into the area, the hike is an easy one to a large rock field on which are hundreds of dinosaur tracks. Most are weathered, but there are three-toed ones that are easy to discern.

The tracks are preserved in what is called the Curtis Formation, a vast expanse of sand deposited some 160 million years ago along the coast of an interior seaway that scientists call the Sundance Sea. Numerous tracksites have been found along the coast of this sea which form the Moab Megatracksite of which the Dinosaur Stomping Ground is a part. It has more than 2,300 single dinosaur tracks in a two-acre area.

Most of the tracks belong to three-toed carnivorous theropod dinosaurs. They may have gathered at the coastline to fish or feed on large dead marine animals that washed ashore. This behavior would be similar to what has been observed in modern animals that feed for weeks on whales whose bodies wash ashore. No dinosaur bones have been found in the Curtis Formation in spite of the huge concentration of tracks there.

Geological evidence indicates that a vast desert with fields of sand dunes surrounded the Sundance Sea.

Some of the tracks in the area are from ornithopod dinosaurs, which also were three-toed but were primarily plant eating. They are distinct animals from theropods, but their tracks can be hard to tell apart if mud has filled in the claw marks left by theropods.

In some places on the tracksite, tiny three-toed prints have been found that may be from small ornithopods or theropods about the size of chickens. There also are large potholes that could be eroded tracks of long-necked sauropods.

Copper Ridge Dinosaur Trackway, near Moab, Utah

The Copper Ridge Dinosaur Tracksite preserves the tracks of a long-necked herbivorus sauropod along with two different sizes of meat-eating theropod tracks. The site was the first place in Utah where sauropod tracks were discovered. It is unusual in that it shows the tracks of a large sauropod similar to the long-necked Camarasaurus or Diplodocus making a right turn roughly 150 million years ago (see the photo below). Paleontologists have yet to find other evidence showing a dinosaur making an abrupt change in direction.

This is a short 1/3 mile long trail round trip. The tracks are Late Jurassic – 150 million years ago - within the Salt Wash Member of the Morrison Formation.

Tracks of large theropod dinosaurs are relatively common in the Late Jurassic rocks in the western Unied States, but the theropod tracks at this site are unusual because they were left behind by a limping theropod, possibly an Allosaurus. The right-to-left steps are shorter than the left-to-right steps, suggesting the animal was suffering from a leg injury. From these tracks scientists can tell that the animal was moving at a speed of 4.5 miles per hour and was just over 7 feet tall at the hip. There are seven theropod tracks preserved in this trackway, although they sometimes are covered by debris that washes into them.

Willow Springs Dinosaur Trackways, near Moab, Utah

The Willow Springs site has the tracks of human-sized theropods and ornithopods (three-toed tracks) and those from sauropods (long-neck dinosaurs) made over 165 million years ago. The creatures walked on the tidelands of a shallow sea that had sparse oases of tropical forest plants. The sea receded not long after the tracks were made, leaving miles of barren tide flats. The tracks became buried and the mud and sand eventually turned to stone.

There are only a few tracks at the site, but more than 2,500 similar ones have been reported on the outer slopes of the Salt Valley Anticline, a deep depression running the length of Arches National Park. There are tracks in the park and on state and other federal land.

Paleontologists are uncertain why so many predator dinosaurs were in this area at about the same time when they are not believed to have run in herds. The scientists also do not know what the dinosaurs ate on the barren tide flats or how the tracks were preserved from being destroyed by the tide.

Poison Spider Dinosaur Trackway, near Moab, Utah

This trackway has two vertical slabs on which are imprinted dinosaur tracks. They are accessed by a 1/4-mile steep hike that is dangerous for small children and has steep drop offs. The trail, which winds back and forth in switchbacks along the steep hillside, also is somewhat confusing to follow.

One of the slabs is near the base of the cliffs at the top of the trail and the other is halfway down the hill, with a steep drop off near it. The lower slab has tracks of at least ten different meat-eating dinosaurs ranging in size from 17 inches to about 5 feet tall at the hips. The track slabs fell from what are called the Navajo Sandstone Cliffs on the red slopes of the Kayenta Formation. Theropod dinosaur tracks are fairly common in the Early Jurassic rocks of the Navajo Sandstone in the Moab area.

Ancient Native American pictographs also can be seen on the cliffs.

Bull Canyon Dinosaur Tracks, near Moab, Utah

This small group of dinosaur tracks look like the animals walked off of a cliff, but that impression is deceptive because the cliff and mountains beyond the tracks didn’t exist when the dinosaur that made the tracks was alive.

The environment when the dinosaurs were there was a shallow, sandy coastal plain just above sea level. The plain hardened later into what is called the Entrada Sandstone layer. Lift up from faulting and erosion created the cliff and the La Sal Mountains behind it.

Prehistoric Museum, Price, Utah

This dinosaur and prehistoric art museum has a world-famous collection of dinosaur tracks found in the coal mines around the mining town of Price, Utah.

Price-area mines are famous for their dinosaur tracks. Among them is a huge Hadrosaur (duck-billed dinosaur) track found at the Royal Coal Mine that for many years was the largest dinosaur track ever found. It is a little deceptive, because the area at the bottom end of the track is not part of the footprint, but a mark where the animal slipped in the mud.

The tracks formed when sand filled footprints that were made by dinosaurs while walking in a swamp, and the filled-in tracks eventually fossilized and were buried deep in the earth. Mining coal revealed the tracks. Rounded three-toed tracks were made by hadrosaurs. Long three-toed tracks were made by carnivorous dinosaurs, and short four or five-toed tracks were made by horned dinosaurs.

At least eight different track types have been found within 100 meters on the Kenilworth Mine’s roof surface. Fossilized plants such as coalified logs and petrified tree roots have also been found. The photo below shows a map of dinosaur tracks made of them on the mine's roof, along with some of the tracks.

Visiting these dinosaur tracksites carries with it a legal responsibility to protect these irreplacable fossils. Here’s how:

Don’t touch them or try to remove them. Removing any fossilized vertebrate footprints, bones or teeth from public lands or molding, casting or tracing them without a scientific research permit is illegal. Defacing, collecting or altering any the tracks also is illegal.

Don’t try to remove sediment from them so you can see them more easily, as this can damage the tracks.

If you find one outside of an area that is designated as a dinosaur tracksite, leave them in place, document them with photos and a GPS reading if possible so that they can be found and preserved by the authorities, and take notes on any distinguishing landmarks or proximity to roads that would help experts find them.

Depending on where the tracks are located, contact the Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, U.S. Forest Service, state land agency, local museum or local law enforcement so they can investigate and preserve the tracks.

Check out these related items

Utah’s Rock Stars

Utah's spectacular scenery harbors one of the world's most complete and diverse dinosaur fossil records.

Going On A Mammoth Hunt

Scientists are stitching together a DNA sequence to produce a living mammoth as well as learning more about the chubby long-haired giant.

Dinosaur Gateway

To put flesh on those enormous dinosaur bones you see at museums, head for the dinosaur park in Ogden, Utah.