Battle of the Samurai

Photos by Forrest Anderson and historical artwork

Appearing like dew, vanishing like dew — such is my life. Even Naniwa's [Osaka's] splendor is a dream within a dream.

— Toyotomi Hideyoshi on his deathbed in 1598

This poem by one of the three great unifiers of Japan reflected his fear in the last moments of his life that the power structure and clan he spent his life building would fail and vanish.

Hideyoshi was leaving behind only a child heir and the dubious promises of five warlords to serve as the child's regents until he became old enough to assume his warrior father’s leading role. As it turned out, Hideyoshi’s melancholy poem foretold one of Japan’s great historical turning points – the fall of the Toyotomi clan and the rise in its place of the Tokugawa shogunate that ruled Japan from 1603 to 1868.

In a park in Osaka, Japan, Toyotomi's reconstructed 16th century castle tower has become the symbol of this pivotal era. On this site, thousands of warrior monks and then samurai fell in battle and vanquished generals were beheaded. And nearby, Allied World War II bombers leveled a large arsenal on August 14, 1945, to drive home to Japanese leaders the imperative to surrender. In the now peaceful park, where people come to view cherry blossoms in the spring, the tower is a reminder of the violence that gave birth to modern Japan.

The castle's appearance is softened by lawns that grow in some of its drained moats. Pleasure boats float on parts of moats that still contain water. The keep is a museum that extolls Hideyoshi’s life.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, when a disunified Japan fell into a chaotic era of small independent states fighting among themselves, many of them built small castles on mountaintops for defense. They gathered around them forces of samurai who defended the castles. The introduction of firearms into the country reinforced the need for strong thick castle walls and castles evolved into stone ones, among which Osaka Castle became the largest. These castles served as regional administrative and military headquarters for warlords or daimyos and as symbols of authority as well as the centers of towns.

In a series of samurai battles against the lords of these small states, the first of Japan’s great unifiers, Oda Nubunaga, established authority over Japan’s main islands in the latter half of the 16th century. His talented retainer and successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, continued this process. Large castles were built to consolidate areas gained in warfare. These castles served as regional administrative and military headquarters and symbols of authority as well as the centers of castle towns. After Japan’s feudal age ended in 1868, many were destroyed as unwelcome relics of a feudal past or in World War II. Only a few dating from the feudal era survive today. Several dozen others have been reconstructed as historical sites using concrete. The most prominent of these is Osaka Castle, which was Hideyoshi’s home base.

The typical Japanese castle was made up of multiple rings of walls, with a main circle in the center and other circles or sections outside of it. Samurai who defended the castles lived in the towns around them and merchants and artisans lived in specially designated areas. Temple and entertainment districts were in the outskirts of cities or outside them.

The castles had high stone foundations and walls while the buildings were constructed of wood. Most had main keeps or towers, walls and moats, guard towers and well defended entrance gates, typically with two gates that created a small inner yard that could be defended from all sides. The castles also contained opulent palaces housing their lord’s residence and offices.

The site on which Hideyoshi built Osaka Castle in the major trading center of Osaka had briefly been the site of two palaces in the 7th and 8th centuries when the town was the ancient capital Naniwa. In 1496, It became a fortress-temple of a group of warrior Buddhist monks and commoners who opposed samurai rule. The temple was patrolled by about 100 monks, and 10,000 of them could be called to battle by ringing a bell. They had many allies who were rivals of Oda Nobunaga.

To consolidate his power, Oda Nobunaga laid siege to the temple off and on for 11 years, the longest siege in Japanese history, until the temple’s abbot surrendered. The complex was burned and the sect was destroyed as a military force.

Three years later, Oda Nobunaga’s follower Hideyoshi began constructing Osaka Castle on the site of the temple. He modeled it on Oda Nobunaga’s headquarters, but made it larger and stronger. The eight-story main tower had gold leaf on its sides to impress and intimidate those who visited it. He expanded the castle to make it more impregnable to attackers.

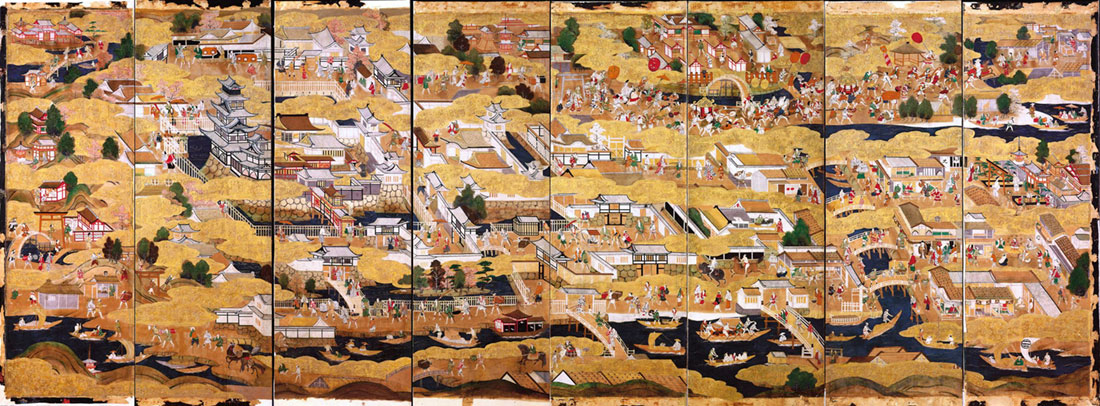

A painting of the castle during the Toyotomi era shows boats on the moats around it. The castle has natural waterways on several sides and was supplied through the port of Osaka which also brought wealth to the Toyotomi clan.

Today, pleasure boats float on the moat.

Hideyoshi, whose base was at Osaka but who spent much of his time on military campaigns, wrote many letters to his wife Kitanomandokoro, who alternated her time between Osaka and the Japanese capital of Kyoto. An intelligent and capable woman, she took charge of much of the administration of his castles and private affairs while he was gone. In his letters, he expressed to her his overarching ambitions.

“I shall take control over China during our lifetime,” he wrote her in 1587. “If [either Korea or China] look down on me, it will be difficult work. During this campaign, more and more grey hairs have grown, and I have not plucked them out. I would not want to see anyone, but I know that you would not mind. But I hate this. “

His Korea campaign worried his wife so much that she asked the emperor to issue an edict to stop it. Kitanomandokoro was one of 300 women in Osaka Castle, among whom also were Hideyoshi’s concubines.

The couple frequently exchanged letters and gifts.

“You have sent me letters again and again,” he wrote. “I have not replied to you every time one came, but I have read them all with much affection.”

In 1590, he wrote to her, “We surrounded Odawara [Castle] with two or three rings and built double moats and walls. So, not a single enemy can escape. People from the eight domains in Kanto stayed [in Odawara castle,] so if everybody starves to death, the way to Oshu will be wide open. I cannot express how content I am. [Kanto and Oshu] are the third of Japan, so I will be patient. Though it might take time, I will give strict orders and make this [pacification] last forever. This is what all people believe to be good… I will make sure that my name will remain in history, and make a triumphal return….

“P.S. I have caught my enemy in a birdcage so far, so there is absolutely no danger. Please do not worry.”

During the Korean campaigns of 1592-98, which he directed from Japan, he wrote to his wife, “So far, we have occupied many castles in Korea. I have already sent many soldiers to take over the capital of Korea. So, before soon, we should be able to get the capital. Please do not worry… I shall obtain the capital of China, and send people to welcome you [to the Chinese capital].”

The Korean campaigns, in which his troops laid waste to large areas of the Korean peninsula and took tens of thousands of slaves back to Japan, failed when his forces were repulsed by Ming Chinese forces and had to retreat home. The dismal outcome of the campaign weakened his forces and later his son’s in their efforts to dominate Japan.

In 1596, envoys from China’s Ming court traveled to Osaka Castle and formally invested Hideyoshi as King of Japan in a grand ceremony in which retainers kowtowed to him. Many of them were granted honorary Ming court rank at this time. However, it is believed that when Hidehoshi read the official documents from the Ming he was outraged, probably at the implication that he had been made subordinate to the Ming court.

In 1597, Hideyoshi finished the castle and the same year ordered a resumption of the war in Korea after the Chinese disregarded his demands for a princess. This invasion of Korea bogged down. Hideyoshi inflicted immense suffering and destruction on the Koreans and the campaign was abandoned after he died in 1598.

Before his death, he appointed five of the most important warlords with whom he had alliances as a Council of Elders to act as regents for his heir, his five-year-old son Hideyori. Named first among them was Tokugawa Ieyasu, whose troops had not been involved in the Korean conflict and thus had not been weakened by it. The alliance of regents failed when Ieyasu maneuvered to gain power, making pacts with prominent families. By 1600, two camps had formed, an eastern army around Ieyasu and a western one led by a Tokoyomi loyalist, Ishida Matsunari, which used Osaka Castle as his base. On October 21, 1600, 160,000 warriors from the two sides fought the Battle of Sekigahara, considered the greatest samurai battle in history. Ieyasu won and became the undisputed master or shogun of Japan. Iiyasu made his capital at Edo, today’s Tokyo.

After taking power, Ieyasu moved warlords around Japan, increasing or decreasing their land holdings depending on whether they had supported him. Some he beheaded by the sword, samurai-style, or forced to become monks. He created a hostage system by forcing daimyo to send their wives and children to live in Edo under his protection.

Ieyasu confined Hideyori in Osaka Castle and married his son’s daughter to Hideyori at the age of ten. In an effort to protect Hideyori, his guardian propagated the myth of him being effeminate, weak and not very bright. This was dispelled in 1611 when Ieyasu asked Hideyori to attend celebrations naming his son Hidetada his successor as shogun. Hideyori’s mother was suspicious of Ieyasu’s intentions and refused to let Hideyori leave Osaka Castle. Ieyasu tried to reassure the Toyotomi family by placing two of his own sons into the care of two trustworthy daimyo as token hostages. Hideyori met with Ieyasu at Nijo Castle in Kyoto, revealing himself as an intelligent and talented young man with the personality to challenge the Tokugawa clan. The meeting sealed Hideyori’s fate.

Ieyasu had tried to force Hideyori to spend some of the fortune in gold that his father had left him in rebuilding the Great Buddha of Kyoto. The statue had been a pet project of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who had seen the image as a unifying one for Japan. He had forcibly collected offensive weapons of all kinds from minor daimyo, temple officials, farmers, and anyone else he disliked, ostensibly to melt them down for metal parts for the statue. However, he stockpiled most of them and probably issued them to warlords who supported his Korean invasions. He also built the Great Buddha, but it was destroyed in a major earthquake in 1596 (Geological evidence for the earthquake has been found by researchers at Osaka Castle). Iesayu saw the rebuilding of the Buddha as an ideal way to empty Hireyori’s treasury. A second Buddha was partially completed when it was destroyed in a fire in 1602. Work resumed in 1602 and was completed in 1612, without making Hideyori noticeably poorer because his wealth was constantly being added to by his trade and port activities. On the pretext that an inscription on a temple bell Hideyori had financed had insulted Ieyasu and challenged his power, Ieyasu decided to move to wipe out the Toyotomi clan.

Hideyori began to gather a force of ronin, or samurai who had no master, and enemies of the shogunate. In response, Ieyasu marched with 164,000 men on Osaka. He destroyed forts manned with men loyal to Hideyori along the way and then began a siege of the castle on December 4, 1614.

Hideyori’s samurai general, Sanada Yukimara, and 7,000 troops defended the earthwork barbican at the gate and also launched attacks on Ieyasu’s troops. Unable to break into the castle, Ieyasu used imported European cannons to lob shells into the living quarters of Hideyori’s mother, killing two women and narrowly missing Hideyori himself. Hideyori capitulated and began peace negotiations. Ieyasu withdrew his troops, but his troops filled in the castle’s outer and middle moats to greatly weaken the castle’s defences.

When Hideyori continued to recruit troops and started to rebuild the castle’s defenses as well as attack shogun forces near Osaka, the fighting resumed. During the fighting, Sanada became exhausted and sat down on a camp stool. He removed his helmet and calmly told approaching enemy soldiers who he was. He told them he was "no doubt an adversary quite worthy of you, but I am exhausted and can fight no longer. Go on, take my head as your trophy."

They decapitated him, demoralizing Hideyori’s army which was routed. The castle was set on fire. Hideyori and his mother went behind the castle and Hideyori committed seppuku, the Japanese samurai suicide. His mother either did the same or a retainer killed her. Ieyasu’s forces took the castle and Hideyori’s eight-year-old son Toyotomi Kunimatsu was beheaded in Kyoto after he blamed Ieyasu for betraying the Toyotomi clan. Hideyori’s daughter became a nun at a temple and Hideyoshi’s grave was destroyed, ending the Toyotomi clan.

A Japanese painting of the Siege of Osaka Castle.

One of the most poignant documents from the battle is a letter written to a 22-year-old samurai named Kimura Shigenari as he prepared to lead his men at the Siege of Osaka despite his troops being outnumbered. His young wife wrote to him the following farewell letter:

"I know that when two wayfarers take shelter under the same tree and slake their thirst in the same river it has all been determined by their karma from a previous life. For the past few years you and I have shared the same pillow as man and wife who had intended to live and grow old together, and I have become as attached to you as your own shadow. This is what I believed, and I think this is what you have also thought about us.

"But now I have learnt about the final enterprise on which you have decided and, though I cannot be with you to share the grand moment, I rejoice in the knowledge of it. It is said that on the eve of his final battle, the Chinese general, Hsiang Yü, valiant warrior though he was, grieved deeply about leaving Lady Yü, and that (in our own country) Kiso Yoshinaka lamented his parting from Lady Matsudono. I have now abandoned all hope about our future together in this world, and, mindful of their example, I have resolved to take the ultimate step while you are still alive. I shall be waiting for you at the end of what they call the road to death.

"I pray that you may never, never forget the great bounty, deep as the ocean, high as the mountains, that has been bestowed upon us for so many years by our lord, Prince Hideyori."

Kimura Shigenari was killed in the battle and then beheaded. His wife had earlier taken her own life.

The shogunate rebuilt the castle and placed it under a governor who served the shogunate. The shogunate decreed laws allowing only one castle per province and limiting each daimyo to owning only one castle. The shogunate had to grant permission for any castle construction or repairs. Many castles were destroyed to comply with this law.

Ieyasu, who was wounded during the campaign against the Toyotomi clan, died on June 1, 1616, the last of the three great unifiers of Japan. His descendants ruled Japan until 1868.

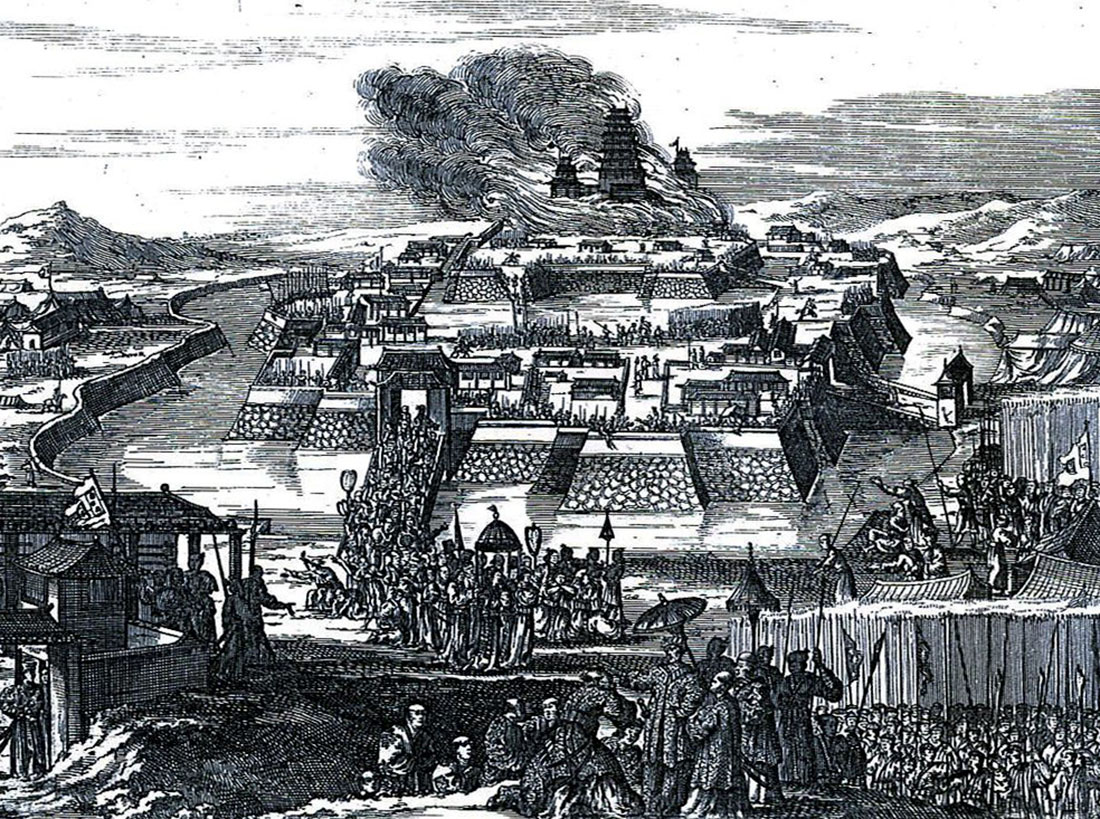

This 17th century drawing by a European of the castle burning shows the keep burning, walls, moat and bridges.

The rebuilt Osaka Castle was struck by lightning in 1660 and again in 1665, when the main tower was burned down. It was not repaired until 1843, when the shogunate collected money to rebuild several turrets. The castle was the site of a battle between shogunate forces and loyalists to the emperor in 1868 and much of it was burned in conflicts during the Meiji restoration. Under the Meiji, the castle became part of an army arsenal that manufactured Western-style guns for Japan’s expanding and modernizing army. An armory there employed 60,000 workers during World War II, one of the largest armories in Japan. As such, it was a prominent target for Allied bombers who destroyed 90 percent of the arsenal, killed 382 employees and damaged the castle tower in the August 14, 1945 raid.

The tower was restored in 1995 by Osaka’s government as a concrete reproduction with a modern interior.

Check out these related items

Traces of an Ancient Superpower

Traces of an ancient Chinese superpower remain far away in Japan, the eastern end of the Silk Road.

A Palace to Remember

Visible traces of the Heijō Palace, Japan's palace from which the emperor ruled in splendor, were gone, until the site was restored.

Giant Buddha, Giant Hall

An emperor built a giant Buddha to unify his struggling country, as the center of a network of Buddhist temples throughout Japan.

Katsura Villa’s Enigmatic Design

Modernist architects admired Katsura Villa as the pinnacle of Japanese architecture and design. It is more complex than they thought.

Japanese Design Past and Present

Architect Kengo Kuma's village at the Portland Japanese Garden blends modern architecture with traditional Japanese design.

Retreat by Design

What makes a retreat restful and soul restoring? A former imperial retreat in Kyoto, Japan, gets retreat design just right.