China’s Stone Scriptures

Photos by Forrest Anderson

Buddhist monk Jing Wen was convinced that his religion was heading for an apocalyptic end. Small wonder he was worried. Jing was the abbot of the Temple that Dwells in the Clouds, or Yunju Temple, at the foot of Shijing Hill, 70 miles southwest of what is now Beijing, China. In Jing Wen’s day (the 6th century), the area was centuries away from becoming a national capitol. The area changed hands regularly and violently as competing states fought to gain control of northern China.

Some of those states were openly hostile to Buddhism. Emperor Wu of the Northern Zhou state banned both Buddhism and Daoism outright in 574, after deciding that Confucianists had won a debate between practitioners of the three religions. He appropriated the wealth and property of Buddhist temples and forced Buddhist monks to return to lay life. He conquered the state of Qi in 577, which placed the temple and Shijing Hill under his rule. Fortunately for the Yunju Temple, Wu died the next year and the regent who rose to power declared himself the emperor of a new dynasty, the Sui, in 581. He reversed the ban on Buddhism and promoted the faith as the state religion until he died in 604. His successor was a brutal militarist who conscripted so many men into his army that there was a farm labor shortage and a drop in agricultural production. He was forced into retirement in 617 by an aristocratic family, the Lis. His 13-year-old successor was strangled, and the Lis declared themselves the rulers of a new dynasty, the Tang. The upshot was that rulers of the time alternately used Buddhism as a state ideology to show they were divinely favored and attacked the religion to appropriate its monasteries’ wealth and land.

In this mercurial atmosphere, Jing became convinced that Buddhism was in a catastrophic third phase of the Dharma in which it would disappear. This was a distinctly Chinese idea that had been prophesied for centuries. The doctrine held that Buddhism had three ages – the age of the true Dharma or remembered words of the Buddha; the age of the semblance Dharma when people went through the motions but didn’t attain liberation and enlightenment; and the age of the end of the Dharma when it would gradually disappear until nothing was left of it. At the end of these three stages, the new Buddha, Maitreya, was to appear to restore the Dharma and start the cycle over again. This view became highly influential in major schools of East Asian Buddhism in the 6th century and was part of some sutras.

Jing turned to a project of preserving Buddhist scriptures so that they could survive the third phase and could help restore Buddhism in future times. The temple had a library of scriptures, but it was vulnerable to being sacked, burned or otherwise destroyed.

The importance of scripture in Buddhist tradition cannot be overstated. Throughout Buddhist history, monks have exerted herculean efforts to copy, preserve and pass on scriptures. To do so, Jing couldn’t just grab a Buddhist version of the Bible or the Koran and bury or hide them. The canonical literature of Buddhism is unique among the world’s scriptures because it is of an enormous size and there are a number of different regional, linguistic and sectarian canons. Few Buddhist texts can be found across all of the religion’s traditions. Each canon contains a large number of texts, some of which are of great length. The Chinese canon covers some 100,000 pages in its printed form. A Buddhist canon is a library, not a small set of texts.

Writing, copying, printing and preserving the canons is a massive undertaking that requires sizable resources from large groups of believers and/or governments. Only a small percentage of Buddhists ever read the whole of the canons, but they still are considered objects of veneration. The scale of a canonical library can place it at great risk at times of military and dynastic instability or anti-Buddhist sentiment. In this case, such a library was at the Yunju Temple.

During the Buddha’s lifetime, he taught orally using either the Pali or Magadhi languages. Monks memorized his teachings through daily recitation and recited them for followers. The recitations included the Dharma and rules of conduct for those who lived a monastic life. In the first century after the Buddha’s death, the canon expanded to include literature that organized teachings found in the sutras into categories. This three-part collection was referred to as Three Baskets, or the Tripitaka. After centuries, these were written down. As Buddhism grew and split into contending schools, they argued over which texts were canonical.

Canonical texts were transmitted along with the spread of Buddhism. This was the era when the brilliant Chinese monk Xuanzang travelled to and from India bringing Buddhist scriptures back to China and translating them. Translating Indian texts into Chinese was formidable because of substantial differences between the languages. The Chinese carried on translating the canon for more than a thousand years, preserving hundreds of texts that have disappeared elsewhere. Some Chinese texts are closer in content to original Indian texts than extant Sanskrit manuscripts of India and Nepal. The Chinese canon in turn was used for translations into other Asian languages. The Pali and Chinese canons eventually became among the most prominent, following literacy traditions in Asia in which Indian and Chinese sources are often the first written texts.

Canonic lists were established by the fourth century in China, largely through catalogs of the holdings of monastic libraries. As the canon grew, copying it became an on-going industry.

In this environment, Jing decided that it was his duty to create a version of the most important sutras on stone stelae. We know Jing’s thoughts because as he carried out his project, he left progress reports carved in stone. In 628, he wrote that “we have been immersed in the decline of the Dharma for seventy-five years."

"The True Dharma and the Semblance Dharma, too, have been lost in the depths, all living beings are heavily stained and faithful hearts are no more.... I fear for the day when the scriptures will disintegrate and dissolve, for paper and palm leaves are hard to maintain for a long period of time. Whenever I ponder these matters my tears flow in compassion and sorrow," he wrote. He left carved instructions that a stone version of the Nirvana Sutra should not be disturbed until Buddhist teachings disappeared from the world.

Sutras carved in stone had a precedent that began around 550 with large carvings at sacred Mount Tai and some carvings of stone sutras elsewhere. However, Jing and his successors kept on carving until they eventually amassed by far the largest collection of stone sutras in China.

As Jing conceived his project, the Emperor Yangdi and his entourage toured nearby Zhuo county in 611, probably in preparation for a military campaign that occurred the next year. A younger brother of the Empress Lady Xiao who was on the tour heard about the stone stele project. A devout Buddhist, he arranged for a donation of 1,000 rolls of silk and other valuable goods to the project. Silk then functioned as currency for high-value projects, as a bolt of silk was worth about 1,000 copper coins. Other elites joined in with donations, and the temple became wealthy overnight.

Jing first extended a natural cave called Leiyin Cave in the hill above the temple and made it into a shrine, the walls of which were covered with some 146 stone slabs on which 19 important sutras and other texts were carved. Half of the wall space was taken up with complete copies of the Saddharmapuṇḍarikā-sūtra and the Vimalakīrtinirdeśa. It’s possible that the Xiao family donation influenced the choice of the Saddharmapuṇḍarikā-sūtra, because their devotion to that sutra was famous. The cave provides a snapshot of what texts were important to Buddhists in the 6th century. Some of the carvings were short excerpts about ethics and monastic etiquette. The cave had four stone pillars supporting the roof which were decorated with carved figures of Buddhas and their names, from a sutra listing 1,000 Buddhas.

Leiyin cave, the walls of which are covered in stone stelae with sutras and other Buddhist texts carved on them.

The cave also housed a Buddhist statue that was removed in the 1940s and is now lost. A stone stele on a rest stop pavilion referred to Buddhist bone relics or śarīra in the cave. Based on the stele’s inscription, archeologists in 1981 rediscovered the bone relics, which were donated by the emperor in 616 after an Indian monk gave them to him. The relics still are at the temple.

Carved sutras on the walls of Leiyin Cave.

The initial phase of the project was completed by 616. Jing moved on to stone stelae of the Buddhist canon, carved on both sides and stored in eight other caves. The stelae were stacked closely together with instructions from Jing that they were not to be disturbed. When each cave was filled, its large stone door was sealed. It appears that a tenth cave was started but never completed.

The cave area.

Jing didn’t actually carve the stone stelae himself. They were prepared for engraving at another nearby monastery that no longer exists. An expert calligrapher brushed the text onto the stones and engravers used the inked-on characters as a guide to carve them. The engravers were lay craftsmen who worked under monks’ supervision.

Once a year on the Buddha’s birthday, local people flocked to the temple for a ritual in which the faithful carried the tablets up the hill to be stored.

The stone stelae carved each year were stacked in the caves during the annual Buddha's birthday ritual.

We know about the history of the temple and stelae from historical records, the oldest of which was written by a government official named Tang Lin and published in 653. Tang was a vice president of the Censorate, a watchdog branch of the imperial government that ferreted out and eliminated official corruption. It reported directly to the government. Tang recorded that he visited the region in 645 and officials told him about Jing’s project. Tang never went to the temple and he muddled the story a bit, but scholars agree that he was referring to Yunju Temple. Tang’s point was to record miracles that had happened at the temple. He reported that it was extremely expensive to build because the region had no forests from which large logs could be procured for supporting columns. One night there was a storm in which the nearby river flooded. A number of sizable logs floated down the river from a distant mountain and were used to build the temple. There were other miracles associated with the site, including animals of the region roaring three times and trees blooming when the carving of the Nirvana Sutra was completed.

Jing’s vow set in motion more than a thousand years of carving sutras on stone stelae. Through seven Chinese dynasties – the Sui, Tang, Liao, Jin, Yuan, Ming and Qing – stones were carved until there were 1,122 Buddhist scriptures carved on 14,279 pieces of stone. The project contains 30 million characters.

Besides the stelae, the Yunju Temple houses more than 22,000 scrolls of rare printed or manuscript Buddhist sutras, including the Ming Dynasty Yongle Southern Tripitaka of 1420 and the Yongle Northern Tripitaka of 1440 as well as handwritten copies by ordinary people. The collection surpasses all other Buddhist ones in China in its content and abundance. It includes the Avatamsaka Sutra or Blood Sutra, written with a mixture of cinnabar and blood from the tip of the monk Zu Hui’s tongue. Yunju Temple also contains 77,000 fragments from one of two extant sets of printing wood blocks of the Chinese Tripitaka, carved between 1733 and 1738. This is considered the greatest sutra of its kind in China.

The Chinese Tripitaka is among China’s key historical documents, having profoundly influenced Chinese philosophy, history, linguistics, writing system, literature, art, calendar, astronomy, architecture, international relations and medicine. More than 30 editions of it have been printed over the past 2,000 years. The stone stelae collection also has six Taoist stelae, three of which duplicate the same text. The temple’s collection rivals and complements the documents of the famous Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, Gansu Province far to the west.

The temple also has a Tang dynasty (618-907) stone pagoda, one of eight in the Beijing area. Inscriptions on the pagoda refer to the stone scriptures and the relationship between the central government and the then-provincial town of Youzhou that was Beijing.

AfterJing’s death, the money ran out and the temple started accepting donations for engraving specific sutras, which was believed to earn donors or their family members a better rebirth. This began with the carving of the monk Xuanzang’s 649 translation of the Heart Sutra in 661, the oldest extant copy of the translation. Many copies of more than 100 different sutras were carved. One covered 120 stelae and was stored in its own cave. Another covered 1,500 stelae. Those carved during the Tang dynasty are the largest extant collection of Tang-era documents.

The carving continued for more than a millennium, until the last one was carved in 1691. The 4,196 stelae carved during the Tang and Sui dynasties from 611 until 907 varied in size and were engraved on both sides with text, images of Buddhas and bodhisattvas, and Siddham letters, a medieval script in which were written many Buddhist texts that were taken to China along the Silk Road. This syllable-based script was considered important in preserving the pronunciation of mantras.

Many of the stelae are dated, so it is possible to know when the carving project ebbed and flowed. The dates also help in providing information about the political, economic and cultural conditions of the area at different times. Many of the stones’ donors were military or civilian officials, and the stones help supplement other historical materials about them and the era. The stones included their ancestral hometowns and information about the administration of the area as well as the layout of the city which was a predecessor to Beijing. The carving largely stopped in unsettled periods between dynasties. For example, there are no carvings from the Tang dynasty after the year 863, perhaps because of anti-Buddhist sentiment during that time.

After the caves filled up, a new cavern was opened near the South Pagoda on the temple grounds. It is there that more than 10,000 stones from the Liao and Jin dynasties were buried.

Site of the Liao-era South Pagoda which once stood in the Yunju Temple grounds.

When the Khitan people took over and established the Liao dynasty, they resumed the carving and continued it until 1110. As their interest was in creating a stone version of the block print edition of the Khitan canon, they regularized the size of the stones and each stone had 28 lines with seventeen uniform characters per line. The stones from this period are the equivalent of 13,000 scrolls of the canon. They are important because the main collection of the Khitan has almost completely disappeared in any other form. Considered highly accurate, the stone sutras have been used to correct later printed versions of the Tripitaka. The stelae also include more than 50 canonical scriptures not found in other versions of the Tripitaka.

There was a break in the carving for 22 years until the next dynasty, the Jin, resumed the work and added a large number of stones over about half a century, continuing the systematic carving of the canon using the print block format. No carving was done during the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368). A Korean monk named Huiyue traveled to Shijing Hill on a pilgrimage during this time and found that Leiyin Cave and the carvings had been damaged and local people were using some of the stones in construction projects.

There was an upsurge of interest during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) when the Buddhist monk Daguan found the relics hidden in Leiyin Cave and showed them to the Emperor Shenzong and Empress Dowager Cisheng. Officials and the elite flocked to the hill and donated money for the carving of a few Buddhist sutras and preservation of the artifacts there. During the subsequent Qing dynasty (1644-1912), the monk Mingbo renovated Yunju Temple. The caves on Shijing Hill and in Yunju Temple had been sealed, so he had a few sutra tablets erected in front of the Buddha hall in the temple and beside the caverns.

After the Qing dynasty fell in 1912, the site again languished until after the Communists took over China in 1949. Artisans began making rubbings of some of the stone stelae. Interest in the rubbings grew in 1955 during celebrations of the 2,500th anniversary of Buddha’s enlightenment when a report was written about the stone sutras and other rare historical documents at Yunju Temple. Excavation of the stone sutras began in the spring of 1956. The excavated stone stelae were cleaned and numbered.

Of the nine caves of scriptures, seven are on one floor and two, including Leiyin Cave, are on the second floor. Leiyin Cave has four stone pillars on which are carved 1,056 figures of the Buddha. Stone sutras found in the caves were placed vertically on a lower level and laid flat or piled randomly in upper layers.

There is a story from the 1950s of Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru visiting Shijing Hill with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai and offering the stones’ weight in gold for them because of their connection to early Buddhism in India. Zhou declined, saying that “gold has a price, but the stone sutras are priceless.”

The caves had been excavated and their stones unearthed by 1958. A process of creating ink rubbings of the stones commenced. This process required large amounts of paper and Chinese ink sticks, which were carried up the hill on motorcycles. The sticks were rubbed with water on ink slabs until they liquified, then the liquid ink was applied to the stones. Paper was pressed over the inked stones, creating a paper negative of each stone. When this process was complete, the sutras were returned to their previous arrangement in the caves and the caves were sealed again except for Leiyin Cave.

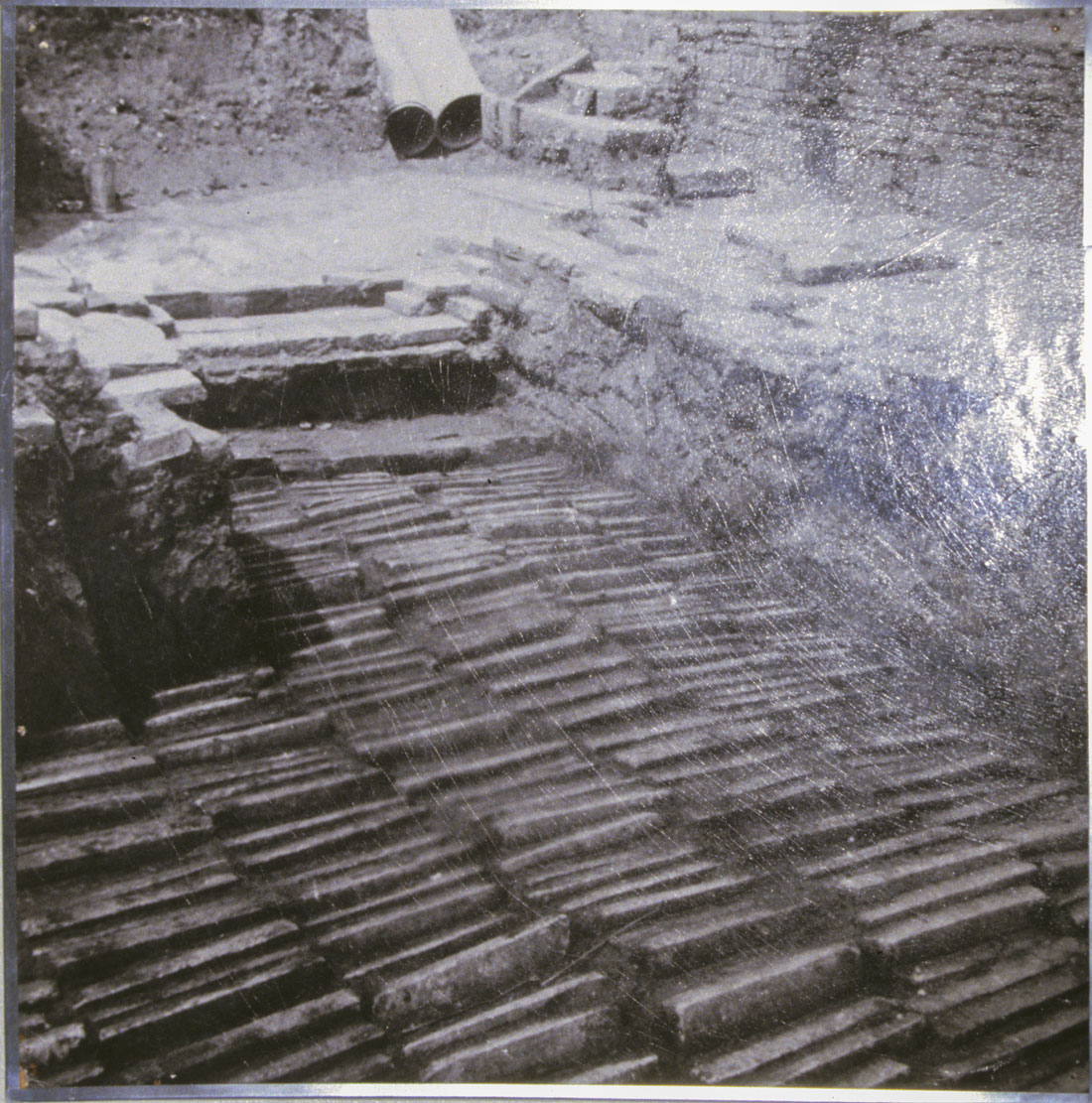

The team then moved down the hill to the temple in search of more caverns which historical records indicated were underneath the temple’s South Pagoda. Japanese bombing during World War II had badly damaged the temple and destroyed the pagoda, but its base had survived and the entrance to a cavern was found underneath it. It contained 10,082 stone stelae carved during the Liao and Jin dynasties. Rubbings were made of these stones as well. A total of 30,000 rubbings were made of the stones.

A 1950s photo of some of the 10,000 Liao and Jin dynasty stelae when they were found.

The scriptures were systematically numbered and catalogued in addition to rubbings being made of them. After it became apparent that they were being damaged by the air, they were moved to an oxygen-free environment where some of them now can be viewed through glass windows.

The research halted during the radical 1966-76 Cultural Revolution, when academics and religious believers were persecuted and China’s strongman, Mao Tse-tung, criticized China’s imperial history as feudal. A number of institutions got copies of the rubbings, including Fa Yuan Monastery in Beijing. In 1975, research resumed on the contents of the rubbings at the monastery, but was again interrupted when northern China suffered a devastating earthquake. The studies did not resume until 1978.

It took a while to sort the rubbings out, because portions of sutras had been stored in different caves rather than sequentially. Most of the stones were dated on the Buddha’s birthday because that was when the stones were stored in the caves. Whatever cave was opened in a certain year would receive all the stones prepared that year, regardless of their content. A catalogue of the collection was published in 1979 after the Fa Yuan Monastery rubbing copies were sorted, and serious study of the rubbings started in 1983.

Important sutras from the collection were published and the entire collection was published in 30 volumes in 2000. It has become the main way for scholars to access the collection.

Since then, the Temple has been restored and an underground museum created so that people can view the stelae that were found under the pagoda through glass windows. The stelae are stored in airtight conditions, both in the underground museum and in the caves.

An upper part of Yunju Temple also has been restored. The area has twelve pagodas dating from the Tang and Liao Dynasties and three Qing dynasty tomb pagodas. The North Pagoda has a distinctive style because of renovations in different eras. Its reliefs are an important resource for the study of the Khitan people. Five of the pagodas together make a grouping that is a prime example of a style of five-pagoda temples.

In one sense, Jing’s dream of the stelae launching a new era of Buddhism in a future time has been realized. The rubbings have been studied by experts worldwide, launching new fields of study of ancient calligraphy, Buddhist architecture, the temple’s history, the history of the town that preceded Beijing, Buddhist scriptures and ancient and modern medicine. The stelae provide insights into Buddhist texts and practices in medieval China.

Past editions of the Chinese Tripitaka did not include all significant Chinese Buddhist scriptures and scholars referred mainly to a Japanese version produced in the 1920s and 1930s for reference. However, this version didn’t include the scriptures found at Dunhuang and Shijing Hill. Beginning in the 1960s, the Chinese government decided to produce a comprehensive version of the Chinese Tripitaka in three parts.The first part would be Buddhist scriptures documented in the Tripitaka of various dynasties. It was finished and published in 106 books in 1994, but scholars found it difficult to use because it wasn’t divided into paragraphs and punctuated.

The government decided to do an updated edition. All existing Buddhist classics and works dated before 1950 and scriptures not included in existing editions were to be included. The new edition was to be in a unified style using traditional Chinese characters and divided into paragraphs and punctuated. More than 100 scholars and monks from across the world were included in the effort. Various Buddhist communities also have moved into the digital age, working on computerized versions of their canons and translations into different languages as Buddhism has spread worldwide.

Check out these related items

Ancient Silk Road Meets High Tech

The International Dunhuang Project digitizes old documents, caves and artifacts to enable global study of Central Asian history.

Islam in China

Muslims in China are a diverse religious and cultural group with a tumultuous history who take various sides in political disputes.

China’s Walled Cities

Only scattered remnants survive of the many walled cities that once defined the Chinese empire.

Traces of an Ancient Superpower

Traces of an ancient Chinese superpower remain far away in Japan, the eastern end of the Silk Road.

A Palace to Remember

Visible traces of the Heijō Palace, Japan's palace from which the emperor ruled in splendor, were gone, until the site was restored.

Treasure Room and Two Palaces

In the French palace at Fontainebleau is a treasure room of dazzling artifacts taken by the French army from a palace in Beijing.