Islam in China

Photos by Forrest Anderson

The Chinese government, which has been criticized internationally for detaining large numbers of Muslims in camps in Xinjiang in western China, announced on Tuesday that some 90 percent of them had been "returned to society" and their families. The camps were estimated to be holding a million or more Uighurs and other ethnic Muslims.

The detentions have sparked growing international criticism and the Trump administration had threatened to impose sanctions over the issue, which U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo characterized as "the stain of the century." There was no immediate independent confirmation of the claimed releases and Uyghurs living abroad said they continued to be unable to reach relatives who were believed to be detained, either by phone or the Internet.

Alken Tuniaz, vice chairman of Xinjiang, made the announcement at a news conference in Beijing, characterizing the camps as education and training centers and the detainees as students. Xinjiang officials have maintained that the camps provided Chinese-language instruction, vocational training and other classes, but former detainees who have left China said the camps were harsh indoctrination centers aimed at getting them to replace their Muslim beliefs with loyalty to China and its ruling Communist Party. Some who have studied the detentions have said that it was possible the detainees had been moved to work in factories connected with the camps and were continuing to be monitored heavily.

Twenty-two countries issued a statement earlier this month asking China to halt the mass detention. China replied with a letter signed by 37 ambassadors praising China's human rights record, including its "de-radicalization" policies in Xinjiang.

Xinjiang's regional chairman, Shohrat Zakir, said at the news conference that people from the camps "have found suitable work to their liking with an impressive income" and had become a positive factor in society.

The detentions have been the latest development in the tumultuous history of Islam within the Chinese empire. Many people believe that China’s Muslim population is largely confined to western China, where Muslim separatist unrest and the goverment crackdown have been in the news frequently over the past several years. However, the Muslim presence in China is much more diverse than that, intertwined with the culture and history of almost every region of the country. Chinese Muslims have varying ethnic and cultural backgrounds and weigh in on different sides of political issues that reflect their situations within larger Chinese society.

Islam has been practiced in China for 1,400 years. Although Muslims comprise only about 1.6 percent of the country’s population, they have had an influence in China far beyond their numbers because Islam spread widely over China's sea and land trade routes.

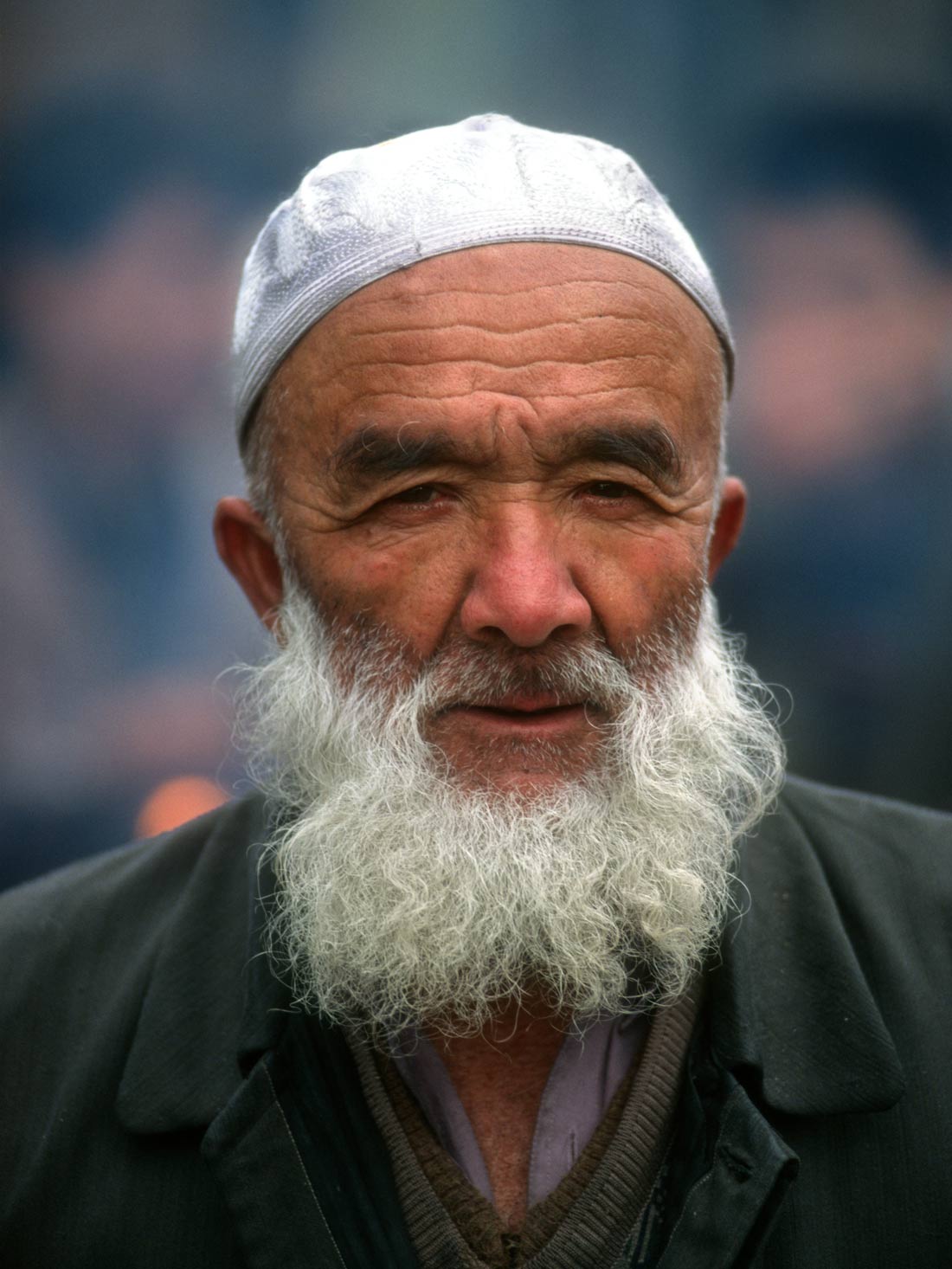

A Chinese Muslim whose dress reflects both his Chinese and Muslim ethnic traditions.

Among the surprises we encountered while living in Beijing was the city's considerable Muslim cultural influence. Popular Muslim foods and customs permeate the culture of Beijing and other parts of northern China, especially along the old Silk Road routes once traveled by Muslim traders. These influences entered our home via our Chinese babysitter, a Beijing Muslim. To accommodate her halal food restrictions, we tried not to cook milk and meat together in meals and to avoid placing pork where she would have to come in contact with it. She in return delighted us by cooking delicious Chinese Muslim versions of Beijing cuisine.

About half of China’s 21 million Muslims are Hui Muslims, while about 40 percent live in the most concentrated Muslim area in China, Xinjiang in western China. The remaining number are smaller ethnic groups that are Muslim. Significant populations of Muslims live in Ningxia, Gansu and Qinghai in northern and western China and there are Muslim communities in major cities as well as some predominantly Muslim counties. Of China's 55 officially recognized minorities, ten groups are predominantly Sunni Muslim. Muslims live predominantly in areas bordering Central Asia known as the Quran Belt - Tibet, Mongolia, Xinjiang, Ningxia, Gansu and Qinghai.

A Chinese Muslim.

Legends say that Islam was introduced into China in 616-618 by companions of the Prophet Muhammed, including his second cousin Sa’ad ibn Abi Waggas who made several trips to China and was an envoy to the Chinese imperial court in 650-651. Modern historians have not confirmed this, but say that Muslim merchants and diplomats did spread Islam in Tang China within a few decades of the religion’s beginning.

The Tang Dynasty had many contacts with Central Asia over both sea and land and there were significant Tang communities of Central and Western Asian merchants in Chinese cities from the 7th to the 10th centuries. During the Tang and Song dynasties, communities of Muslim merchants existed in Guangzhou, Quanzhou and Hangzhou on China’s southeastern coast as well as interior cities of Chang’an, Kaifeng and Yangzhou. Guangzhou's mosques include the famous Huaisheng Mosque believed to have been built by Sa`d ibn Abi Waqqas, whose father may have been buried in Guangzhou. In 758, Arab and Persian pirates raided and looted warehouses in Guangzhou and a large Muslim community there fled.

Historical accounts indicate that a Chinese army went to the aid of Turkish Uyghurs threatened by Islamic invaders in 751 but was defeated. As a result, Islam spread in the defeated areas.

Arabs had flourishing diplomatic relations with the Tang Dynasty. The Chinese emperor Suzong (756-762) asked the Abbasid caliph al-Mansur (754-775) to help quell a Tata revolt in China. The caliph sent 10,000 soldiers who took control of the Chinese capital of Chang’an temporarily.

Because of heavy Muslim involvement in trade during the subsequent Song Dynasty, a Muslim was consistently named the dynasty’s director general of shipping. In 1070, the Song emperor Shenzong invited 5,300 Muslim men from Bukhara to settle in China to create a buffer zone between Song territory and the Liao empire to the northeast. These people settled between the Song capital of Kaifeng and Yanjing, which is modern-day Beijing, but which was part of the Liao empire at the time. The Muslims were led by a man named Prince Amir Sayyidm who the Chinese called "Sofeier." He changed the Chinese name for Islam from "Dashi fa" to "Huihui Jiao," the Religion of the Huihui. In 1080, another 10,000 Arab men and women arrived in China on horseback to join Sofeier, settling in several provinces.

Muslim trader Pu Shougeng later helped the Mongols conquer southern China after Song loyalists tried to prevent the Mongols from taking over the southern city of Fuzhou. The Mongol Yuan dynasty’s official history records that Pu mobilized troops from among foreign residents who massacred the Song emperor's relatives and Song loyalists. Pu was lavishly rewarded by the Mongols and appointed military commissioner for Fujian and Guangdong.

The Mongols allowed traders to travel freely through their empire and repaired the Grand Canal to develop north-south trade, which helped spread Islam as Muslim merchants traveled along the waterway.

The Mongols elevated the status of foreigners such as Muslims, Christians and Jews from West Asia over that of native Chinese. They forcibly relocated hundreds of thousands of Muslims from areas the Mongols had conquered in Western and Central Asia to China to administer the Chinese part of the Mongol empire. The Mongols sent Han Chinese and Khitans from China to do the same in Central Asia. The ideas was to curtail the power of local people by placing over them foreigners whose main tie was to the Mongols.

The Chinese called the Western and Central Asians semu, or “various eye color.” The Semu acted as tax and finance officers, headed commercial enterprises in China, and worked on the calendar and as astronomers. Muslim architect Amir a-Din, known in Chinese as Yeheidie'erding, studied traditional Chinese architecture and then helped design and build the Yuan dynasty capital at what is today Beijing. The city’s Yuan architecture was not the same as today’s, which was built by later dynasties, but the Yuan capital had a similar footprint.

Central Asians, Han Chinese and other ethnic groups within the Mongol empire extensively intermarried during the Yuan dynasty. Foreign trade prospered in the southern Chinese province of Fujian, especially Quanzhou, which was possibly the world’s largest port. Ten thousand ships were said to dock there, exporting silk, ceramics, copper and iron and importing pearls, ivory, rhino horns, and spices. The city had many foreign residents, including Arabs, Persians, Europeans, Jews and Indians, and about 100 languages were spoken there.

A Muslim group in the southern Chinese province of Fujian rebelled against the Mongols in a series of wars in the 14th century called the Persian Sepoy or Ispah Rebellion. Shiite Persians in Quanzhou organized an army, seized Quanzhou and suppressed Sunni Muslims in the area. The Yuan government responded by massacring Arab and Persian merchants and other foreigners in Quanzhou, crushing the uprising. Mosques and other foreign buildings were almost all destroyed and foreign graves desecrated.

The Mongols forbade Islamic practices such as halal butchering, so Muslims secretly slaughtered sheep. The Mongols also forbade circumcision. Toward the end of the Yuan dynasty, when Mongol religious persecution increased, Muslim generals of the Yuan dynasty rebelled along with the Han Chinese against the Mongols. Among the more famous was Muslim general Lan Yu. He led a Ming army north of the Great Wall to defeat the Mongols in their homeland, ending their dream to reconquer China.

The founder of the Ming dynasty, Hongwu, required both Mongol and Central Asian Semu Muslims to marry Han Chinese. Muslims continued to be influential in his dynasty. The Hongwu emperor ordered mosques built in capital cities and in the provinces of Yunnan, Fujian and Guangdong and wrote a eulogy praising the Prophet Muhammed.

The Hongwu emperor’s son, the Yongle emperor, hired Zheng He, who was of Muslim birth although not a Muslim in later life, to lead seven expeditions to the Indian Ocean from 1405 to 1433.

As the Ming Dynasty wore on, it became isolationist and restricted new immigration into China. Muslims descended from earlier immigrants spoke Chinese and adopted Chinese names and culture. Mosques were built using traditional Chinese architecture, including one in Nanjing built by the Xuande emperor. The city of Nanjing became an important center for the study of Islam.

Muslims in Ming Beijing had few restrictions on their religious practices or freedom of worship, unlike adherents to Tibetan Buddhism and Catholicism.

Beijing’s famous Niujie Mosque was built in 996 during the Liao dynasty, but destroyed by Genghis Khan’s armies in 1215. It wasn’t until 1443, during the Ming Dynasty, that it was rebuilt. Muslim eunuchs contributed money to repair the mosque in 1496. It is traditionally Chinese except that it is decorated with Arabic inscriptions inside. It is located in a Muslim district of Beijing.

Worshippers in prayer at Niujie Mosque.

In eastern Chinese mosques such as Niujie Mosque, minarets became Chinese style towers.

Chinese-style steles at the Niujie Mosque tell the story of the historic compound.

The Zhengde emperor was suspected of having converted to Islam, as he preferred Muslim Central Asian concubines. He also used Muslim eunuchs to oversee the production of blue-and-white Chinese porcelain with Persian and Arabic inscriptions.

The Manchus took over China in 1644, launching the Qing Dynasty. Two years later in 1646, Muslim Ming loyalists led a revolt against the Qing which was quelled when the Qing killed 100,000 Muslim loyalists. Muslim loyalists accompanied the Ming Prince Gui when he fled to the Burmese border. They changed their name to Ming in defiance of the Qing. The tombs of three Muslim Ming loyalists who died fighting the Qing are in Guangzhou.

The northwestern region of Xinjiang, now part of China, has had many names and rulers throughout history. As early as the Han Dynasty between the 2nd century B.C. and the 2nd century A.D., Chinese rulers tried to secure the profitable trade routes through the area. During the Qing dynasty, northern Xinjiang was called Dzungaria and was ruled by Tibetan Buddhist nomads. The Tarim Basin had been inhabited by oasis dwelling Turkic Muslim farmers since Turkic Muslims conquered the Saka Buddhist Kingdom of Khotan around 1006. Today’s Uyghurs are a mixture of East Asian Mongol and European Caucasian populations.

The Uyghurs had been conquered by the Dzungars, who imposed heavy taxes on them and forced the Uyghurs to provide women and refreshments to tax collectors. Women were gang raped if the tax collectors did not consider the taxes paid to be satisfactory. The Uyghurs asked the Qing for help in overthrowing Dzungar rule and helped supply the Qing army while it waged a successful military campaign against the Dzungars in 1757. The Qing were ruthless, killing 80 percent of the 500,000-800,000 Dzungars who lived in the Xinjiang area. Surviving Dzungars were relocated to other areas of China, leaving their area depopulated.

The Qing then resettled Han Chinese, Hui, Uyghurs and Xibe people on state farms in Dzungaria along with Qing armies to repopulate the area. The Qing established the towns of Urumqi and Yining. The Qing tried to divide the Xinjiang region into four sub-khanates under chiefs subordinate to the emperor and formed relations with the Ak Taghliq clan of Eastern Turkestan Khojas, who ruled in the western Tarim Basin. However, rebellions broke out quickly.

In 1765, Uyghurs rebelled against the Qing after Uyghur women were gang raped by the servants and son of Qing official Sucheng. The rebels killed Qing forces, including Sucheng, and took over the Qing fortress. The Qing emperor ordered that the oasis town of Ush be massacred in retaliation. All of the Uyghur women and children were enslaved and the men were killed. The Qing defeated another rebellion in 1818-20.

As the Qing dynasty weakened, a number of revolts broke out in in western China from the 1850s-1890s. In the Panthay Revellion which occurred in the southwestern province of Yunnan, the Qing killed a million people. The Qing ordered several million more killed in the Dungan revolt of 1862-1877 in Xinjiang, Shaanxi and Gansu.

The Muslim population in eastern China was apparently unaffected by the western rebellions. Many Muslim generals fought on the Qing side. A Muslim army called the Kansu Braves fought for the Qing dynasty against the foreigners during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900.

Han exiles convicted of crimes were sent to Xinjiang to be slaves of the Qing garrisons there, and Mongol, Russian and Muslim criminals from Mongolia and Inner Asia were sent east to serve as slaves in garrisons in Guangzhou.

The Hui Muslim community was divided in its support for the 1911 revolution that brought down the Qing, with Hui Muslims in Shaanxi supporting the revolutionaries and Hui Muslims of Gansu supporting the Qing. The native Hui Muslims of Xi'an joined Han Chinese revolutionaries in slaughtering the entire 20,000 Manchu population of Xi'an. Young Manchu girls were seized by Hui Muslims during the massacre and brought up as Muslims.

After the fall of the Qing Dynasty, Sun Yat-sen, who established the Republic of China, proclaimed that the country belonged equally to the Han, Manchu, Mongol, Hui Muslim, Tibetan and Miao peoples.

The Nationalist government later appointed Muslim warlords of the Ma family as the military governors of the provinces of Qinghai, Gansu and Ningxia. China’s defense minister was Muslim Bai Chongxi.

During World War II, the Japanese army destroyed 220 mosques and killed countless Hui. The Japanese army massacred people in the Hui Muslim county of Dachang in Hebei province. During the Japanese attack in Nanjing, mosques in the city were filled with dead bodies. Japanese troops smeared Hui mosques with pork fat, forced Hui girls to serve as sex slaves and destroyed Hui cemeteries. Many Muslims fought against Japan during the war.

After the rise of the Communists to power in 1949, Muslim Nationalist forces continued to fight against the Communists until being subdued in 1958.

During the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution, religion was banned. Mosques were damaged, destroyed or closed and Red Guards destroyed copies of the Quran. In 1975, the only large scale ethnic rebellion of the Cultural Revolution, a separatist Hui Muslim uprising in Yunnan, was suppressed. The Communist army killed 1,600 Hui Muslims, firing rockets on their village of Shadian from MiG fighter jets. The government later apologized, issued reparations, erected a Martyr’s Memorial in the town to honor the victims and partially financed the building of a mosque there.

In the 1980s-1990s, Muslims were again allowed to practice their religion. This photo shows a Muslim district of Beijing in the 1990s.

Chinese government policies toward Islam vary by region. In 1989, China banned a book called Sexual Customs and arrested its authors after Muslims in Lanzhou and Beijing protested its content as insulting to Muslims. The government protected the protesters and organized public burnings of the book.

To avoid offending Muslims, CCTV decided not to air some depictions of pigs in 2007 in anticipation of the Year of the Pig in the Chinese calendar. The government has allowed private Islamic schools in areas except for Xinjiang and Hui Muslim students are allowed to study religion under an imam after they have completed secondary school. State employees who are Hui Muslims are allowed to fast during Ramadan, while Uyghur state employees are not. Hui Muslim women are allowed to wear hijabs in many areas, although the practice is not encouraged and many Chinese Muslim women don't wear it. In Xinjiang, veils and the growing of long beards are not allowed.

A Chinese Muslim woman in a head scarf.

Uyghurs have been subjected to a severe crackdown in Xinjiang since rioting in Urumqi was suppressed in 2009. Uyghur dissidents have been detained and academics who promoted Uyghur social interactions have been imprisoned. China has taken a tough stance toward terrorism both domestically and internationally and toward separatists in Xinjiang. From 2012-2017, there was a 306 percent increase in criminal arrests in Xinjiang. Arrests there were 21 percent of the national total even though the region has just 1.5 percent of the population.

All vehicles had to have GPS tracking devices installed. Uighur families were required to allow local government officials to live in their homes as relatives in a "Pair Up and Become Family" campaign. While the official was living in a home, the residents were not allowed to pray or wear religious clothing. Authorities said that the program was voluntary but Muslims expressed concern that refusal to cooperate would lead to serious repercussions.

Hundreds of thousands of Muslims reportedly have been detained in the extra-judicial camps in western Xinjiang. In response to a UN panel's finding of indefinite detention without due process, the Chinese government delegation officially conceded that it was engaging in widespread "resettlement and re-education." Many people also have been alarmed at the government's use of state-of-the-art surveillance technology in Xinjiang.

On 31 August 2018, a UN committee called on the Chinese government to "end the practice of detention without lawful charge, trial and conviction," to release the detained persons, to provide specifics as to the number of interred individuals and the reasons for their detention, and to investigate allegations of "racial, ethnic and ethno-religious profiling."

There have been tensions between Hui Muslims and Uyghurs because Hui troops and officials often have dominated Uyghurs and quelled Uyghur revolts. Xinjiang's Hui population increased by over 520 percent between 1940 and 1982, an average annual growth of 4.4 percent, while the Uyghur population only grew by 1.7 percent. During the 2009 rioting in Xinjiang that killed around 200 people, “Kill the Han, kill the Hui” was a common slogan used on social media by Uyghur extremists. Some Uyghurs in Kashgar recalled that a Hui army had massacred 2,000-8,000 Uyghurs in 1934. Hui and Uyghur live separately and attend different mosques.

Hui Muslims typically see China as their home and the Chinese language as their language, unlike many Uyghurs who see their language and culture as distinct from China’s. Uyghurs have accused Hui Muslim drug dealers of trying to push heroin on Uyghurs.

There also have been incidents of violent fighting between different Hui Muslim sects in Ningxia, and some sects refuse to marry those of other sects. The Salafi movement in Islam is increasing in China because of funding from mosques in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates. Some Hui Salafists have joined the jihadist movement Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.

Muslim and non-Muslim Tibetans have had conflicts in the 20th-21st centuries, including riots in which Tibetan Buddhists attacked Muslim restaurants. In 2008 riots in Tibet, Muslim shops and apartments were burned and Muslims were killed or wounded. Many Muslim men stopped wearing white caps and women scarves for fear of violence against them. They began to pray in secret after the main mosque in Lhasa was burned. There also have been disputes between Chinese-speaking Hui Mosloms and Tibetan speaking Kache Muslims.

Most Tibetans viewed the wars against Iraq and Afghanistan after 9/11 positively. This contributed to anti-Muslim attitudes among Tibetans and a boycott of Muslim-owned businesses. Some non-Muslim Tibetans see attacking Muslims as a way to demonstrate anti-government sentiment and resentment of Hui Muslim economic influence in Tibet. Tibetan Muslims are officially classified as Tibetans rather than as part of other ethnic groups.

Hui Muslims share more genes with Han Chinese and East Asians than with Middle Easterners, indicating that most are descended from East Asian populations that converted to Islam rather than being descendants of foreigners. There are some 36,000 Islamic places of worship, more than 45,000 imams, and 10 Islamic schools in China. In addition to mosque schools and both state-run and private Islamic colleges, many Chinese Muslim students study at international Islamic universities in Egypt, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Iran, and Malaysia.

Most Chinese Muslims are Sunni and follow an orthodox form of Islam. However, a large minority are members of Sufi groups. Shia Chinese Muslims mostly are Ismailis, including Tajiks of the Tashkurgan and Sarikul areas of Xinjiang.

Since 1979, the government has allowed Chinese Muslims to attend the Hajj in Mecca in large numbers.

Like other religions in China, Islam operates under a state-run organization. The Islamic Association of China takes on this role for Muslims. They are allowed to have separate cemeteries, have an imam consecrate their marriages, take holidays during religious festivals and make the Hajj to Mecca.

Islam has influenced China in technology, science, philosophy and art over the centuries. Decorative patterns and calligraphy from central Asian Islamic architecture were brought to China along with Muslim cuisine.

Many Chinese mosques are traditional Chinese temple architecture, although those in western China are more likely to include minarets and domes. In 2018, residents of Weizhou in Ningxia demonstrated over the planned destruction of a mosque by officials who said it had not received proper building permits and was built in a Middle Eastern style with domes and minarets. The destruction was canceled.

The cuisine of northern Chinese cities such as Beijing has been greatly influenced by the Muslim diet. Most major cities have restaurants that cater to Muslims and food stalls run by Muslim migrants from western China. Muslim butchers also offer halal meat. although the government in some cases has discouraged the observance of halal food as a source of religious separatism.

Northern Chinese Islamic cuisine is similar to Beijing cuisine but uses beef prominently because Muslims are prohibited from eating pork. Chinese Muslims also have taken Chinese Islamic food to other countries as they have emigrated to them. Many Chinese regard Hui halal food as especially clean, so Islamic restaurants are popular. Clerics from mosques inspect halal restaurants.

Popular Muslim dishes in Beijing include a stewed beef noodle soup made of beef, broth, vegetables and wheat noodles that was created by the Hui people during the Tang Dynasty. "Yangruo chuanr" or kebabs made with lamb are a popular street food in Beijing and have a Uyghur origin. Round Uyghur bread cooked in very hot ovens also is sold in Beijing.

Beef noodle soup.

This legacy photo shows a Xinjiang-style restaurant in a Muslim district of Beijing.

Xinjiang-style flat bread.

Muslims in China have developed Sini, a Chinese Islamic calligraphic form for the Arabic script that is used in mosques in eastern and northern China. Chinese Muslims also have texts written by Chinese Muslims which blend Islam and Confucianism.

The Chinese form of martial arts called wushu has a long history of Muslim participation, and Hui created and adapted many styles of wushu. Unrelated Turkic styles of martial arts also are practiced in Xinjiang.

China has a long history of foreign relations with Muslim countries and aggressively pursues relations with them today. This has paid off in a number of Muslim countries' siding with Beijing in various international controversaries, including the Chinese government's treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. A wave of Islamic countries originally spoke out against the Uyghur repression but then backed down because of fear of economic repercussions from China. Turkey was among them. The country is home to 35,000 Uyghurs, many of whom fled Xinjiang.

Check out these related items

Ancient Silk Road Meets High Tech

The International Dunhuang Project digitizes old documents, caves and artifacts to enable global study of Central Asian history.

The Summer Palace

The Summer Palace, the most famous and heartbreaking of China's glorious imperial gardens, highlights dilemmas in the nation’s past.

Treasure Room and Two Palaces

In the French palace at Fontainebleau is a treasure room of dazzling artifacts taken by the French army from a palace in Beijing.

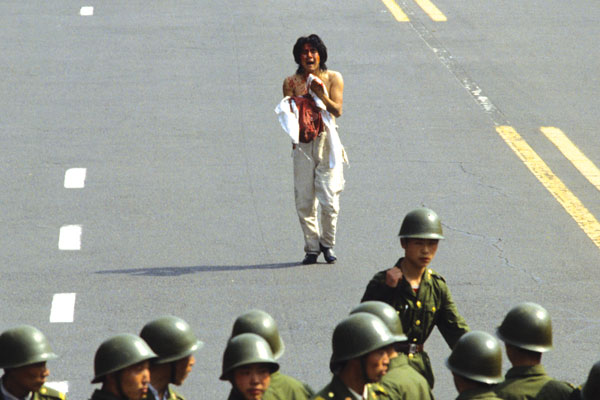

Thirty Years Since Tiananmen

Thirty years ago, students staged pro-democracy protests on Tiananmen Square that shook China's Communist government.

Tiananmen Square

China's Oct. 1 celebration of 70 years of Communist rule centers on Tiananmen Square, one of the world’s most controversial places.

China’s Walled Cities

Only scattered remnants survive of the many walled cities that once defined the Chinese empire.