The Summer Palace

Photos by Forrest Anderson, culled from many visits to the Summer Palace

When a lipstick collection created around the theme of the Summer Palace imperial garden in Beijing went on the market recently, it sold out within 24 hours. The packaging of both this collection and a popular Forbidden City-themed one feature images of artifacts from the two sites, including a screen that belonged to the 19th century Empress Dowager Cixi. 3D printing gives the lipstick tubes the texture of embroidery.

The collections are part of a marketing trend of historic-themed products that capitalize on rising national pride in China. The trend has been fueled by popular historic films and a domestic travel boom that has clogged sites such as the Summer Palace. The historic garden receives about 100,000 visitors per day and has had to close early on some holidays to stay within its peak capacity of 120,000.

The demand for traditional products is driven by Chinese too young to remember the government's suppression of traditional culture during the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution and who have been schooled since the 1990s to associate traditional Chinese culture with the country’s rapid economic growth and international clout. As the ruling Communist Party’s Marxist anti-imperialist legacy faded amid market reforms and globalization, the party has based its legitimacy on restoring Chinese civilization to greatness through modernization and globalization. The imperial past, disparaged under Maoists who considered the emperors appalling parasites who lived in splendor by repressing common people, has returned in all its gaudy glory. Having wholesale destroyed many historic neighborhoods and sites in the 1980s and 1990s in a head-long rush toward modernization, Chinese cities now build traditional-style sections as tourist sites and have restored or reconstructed many historical sites. Maoist Red Guards once smashed priceless porcelains, but both the government and collectors now aggressively collect historic Chinese items at art auctions. Nationalism merges with veneration of the past and current aspirations as wealthy Chinese billionaires bid at auctions for treasures which Anglo-French armies looted from the Summer Palace and nearby Yuanmingyuan garden in 1860 and 1900. At the Yuanmingyuan, 100,000 shattered fragments of porcelain are being meticulously pieced together to put on display. More than a million people, mostly young women, participate in historic reenactment groups in which they dress up in the styles of China’s Han dynasty, and Chinese designers use elements of these costumes in mainstream fashion.

The interest in China's imperial past includes the problematic Qing dynasty legacy represented by the Summer Palace. More than almost any other site, the Summer Palace encapsulates modern China’s complicated relationship with the historical issues that fuel Chinese nationalism today. The Summer Palace raises uncomfortable questions of what it means to be Chinese even as it remains a popular destination spot.

Path at the Summer Palace.

At the crux of the issue is that unlike the Forbidden City, from which both Chinese and foreign emperors ruled China, the Summer Palace was once the opulent private retreat of non-Chinese conquerors who invaded China from the north in 1644 and ruled the Chinese empire as the Qing dynasty until 1911. The garden was part of a vast complex of gardens where the Qing rulers lived, worked and relaxed in secluded opulence from which most Chinese were barred. The area where the gardens were built had a prior history of private gardens, but the Qing gardens were by far the most elaborate and famous. Although the Forbidden City was nominally their main residence, the Qing much preferred the lakes, pavilions and winding paths of the gardens and stayed there as much as possible.

Pond-side building at the Summer Palace.

The gardens, to which they steadily added at great cost to the people of China, were designed to be a miniature version of the world that the Qing rulers claimed to be the center of and the mythological world of the gods, thus representing both the empire and its state ideology. The emperors filled the gardens with priceless porcelains, silks, furniture and jewels made by highly skilled Chinese craftsmen. They dined, watched entertainments, issued edicts, worshipped, boated and strolled among the exquisite pavilions and plants. The height of their rule was under the emperor Qianlong, who commissioned the Summer Palace while expanding China’s territory three-fold into one of the world’s largest empires and encouraging global trade that brought Spanish silver from the New World pouring into China. Native Chinese disliked being ruled by foreign invaders but endured it while the country prospered.

Today, the Chinese are immensely proud of the Qing empire’s size and glory and even use its boundaries as historical evidence in some border disputes, while continuing to resent the Qing invasion and its subordination of Chinese to second-class status in their own land.

Qianlong was the patron of imperial kilns that produced the fabulous porcelain that adorned both his garden and the palaces of European monarchs. However, the flow of silver began to go the other way in the early 19th century as Europeans learned how to make porcelain and other Chinese goods and the British began to sell Indian opium in large quantities to China. When the Qing government tried to staunch the opium trade, British gunboats defeated Chinese armies in a series of Opium Wars and demanded that China open its most prosperous ports to foreign trade. The Chinese signed the treaties but dragged their feet implementing their demands until an impatient Anglo-French army invaded Beijing. In retaliation for the Qing torturing and killing members of a British advance party, the Anglo-French forces sacked and burned the gardens, including art treasures and historical documents, in 1860. This remains among the most contentious events in Chinese history. China’s diplomats, business people, historians and the public trot it out to criticize the West in major disputes over trade or business. The destruction accompanied popular rebellions against the Qing in central and northwestern China as China slowly came apart at the seams.

The invasion and destruction of his home was so traumatic that Emperor Xianfeng, who had fled Beijing, took ill and died the following year. A child emperor was enthroned, and Xianfeng's empress Ci'an and the child's mother, Cixi, ruled as his regents. Ci’an was eventually sidelined, while Cixi as Empress Dowager became the most powerful Chinese ruler of the 19th century and one of the most reviled leaders of Chinese history. Cixi ruled in the name of her son until he died and then as regent for other young male heirs who she tightly controlled for more than 50 years. She clung to power in Beijing until her 1908 death, but was unable to halt the signing of dozens of “unequal" treaties that resulted in vast areas of China being taken over by European powers and Japan.

She is an immensely controversial and reviled figure, accused of selfishly weakening China so that it became vulnerable to foreign aggression and prolonging the life of a corrupt dynasty. China’s defeat at the hands of foreign armies convinced her that China needed limited modernization. Under her rule, China established a modern if weak navy, a foreign service, and a foreign-managed customs service that facilitated trade with Western powers. She also belatedly supported educational reforms, but prevented the young Guangxu emperor from instituting bolder reforms including a constitutional monarchy.

Cixi as a woman had to sit behind a curtain during court meetings so that the ministers couldn’t see her. In modern times, this led to a common Chinese saying that senior officials, particularly Deng Xiaoping, ruled from “behind a curtain” while younger proteges held official positions.

As her country imploded, Cixi had a portion of the Summer Palace rebuilt in 1886. She lived in splendor, with a kitchen that served her 120 dishes a day (she only ate two or three bites of some dishes and passed the rest on to members of the court. She wore embroidered, pearl-encrusted gowns and jade-and-gold jewelry and owned more than 20 dogs, who wore satin clothes embroidered with silk and gold thread. She is particularly detested for her extravagance while China’s inadequate naval fleet was spectacularly defeated by the more technologically advanced Japanese in 1895. Two years earlier, Cixi had an elaborate fake boat at the Summer Palace restored using funds diverted from the navy. The year of the battle, a major hall at the Summer Palace was renovated for her 60th birthday extravaganza. Only a minority of historians see Cixi positively as a strong-willed feminist in a country in which women were notoriously repressed.

When their embassies were beseiged during the anti-foreign Boxer Rebellion, Western armies again invade Beijing in 1900 and sacked the Summer Palace.

The Guangxu emperor died the day before Cixi, in what is widely believed to be murder instigated by Cixi or her courtiers to prevent him from instituting reforms after her death. Imperial records say he died of natural causes, but a 2008 medical examination of his remains indicated that they contained a high concentration of arsenic. The dynasty survived under a child emperor for only four more years.

Cixi drained government coffers even in death. A lavish funeral and almost a year of funeral activities included the burning of a giant funeral boat of wood, covered with silk and filled with paper effigies of towers, chambers, pavilions and life-sized servants. She was buried with a treasure trove of jewelry and luxury items, which were looted by the warlord Sun Dianying and his army in 1928.

The Chinese both detest her and are outraged that the gardens were destroyed by foreign invaders who wrung debilitating concessions from her government. This anger is a main base of support for the Communists, whose bloody revolution restored native Chinese rule to a country largely dominated by foreign invaders since 1644. China's leaders vow that never again will China allow itself to fall behind and lose its sovereignty.

Cixi's extravagance and court life are a source of continuing interest to the Chinese public and a cautionary tale about conspicuous consumption in a land with one of the world’s widest income gaps.

The Summer Palace again was rebuilt just as the dynasty was ending in 1911-12, and opened in 1924 as a public park.

Despite its dubious history, the garden is a masterpiece of craftsmanship and gardening. Some Chinese architectural historians look upon the gaudy Qing style as a step down from the graceful post-and-beam architecture of earlier Chinese-led dynasties such as the Song and Ming, but the garden nonetheless epitomizes the main elements of Chinese gardens. It blends elaborate buildings and natural elements, with paths that take visitors through various planned scenes. Some are miniatures of famous scenic spots elsewhere in China. The gardens draw on a rich 3,000-year history of garden building by emperors and elites.

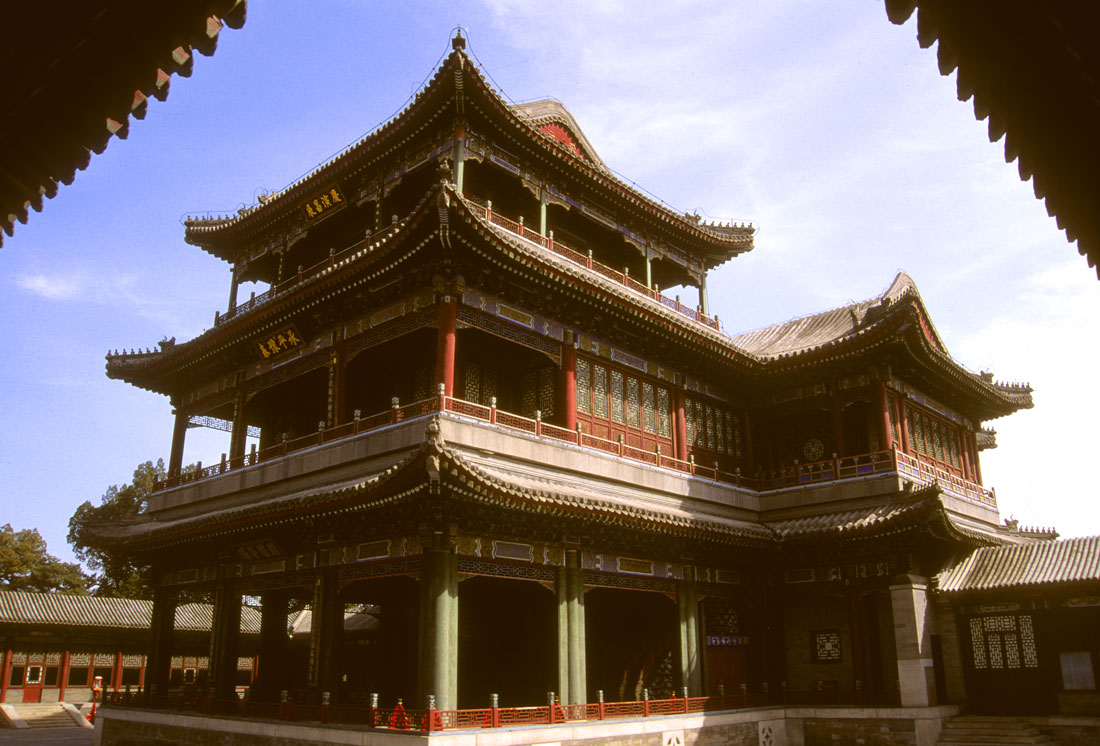

The court area

In the standard Chinese garden tradition, major buildings such as ceremony halls are placed inside the main entrance to the garden and were used for receiving guests and celebrating family holidays. Here Cixi and Guangxu conducted government business. A four-courtyard area, the Garden of Virtue and Harmony, contains a three-story theater that is the largest and best-preserved wooden stage in China. Cixi was a Peking Opera fan and famous actors performed for her on this stage.

Theater in the Garden of Virtue and Harmony.

The summer palace buildings are painted in red, green, yellow and blue, colors that have long been associated with imperial architecture. Red symbolized fire and blood, good fortune and prosperity. Green represents life and growth.Yellow is associated with the emperor, the mythical forefather of the Chinese nation, the Yellow Emperor, and the life-giving Yellow River Basin of China. The Yellow River gets its color from the loess sediment of central China that its waters carry. The roofs are clad in yellow tiles and the emperors wore yellow robes. The color blue symbolizes heaven and heavenly blessings.

The garden buildings include residences, studios, libraries, hallways and pavilions, some of which look out on scenic views that are particularly beautiful at certain seasons. A pavilion used during the summer may face north toward a lotus pond so that cool breezes can blow into it, while one used during the winter faces south to allow sunshine to come in, with evergreens planted in front of it. Some pavilions are for viewing spring blossoms and others autumn foliage or the rain.

Water

Water, a key feature of Chinese gardens, usually is in the center in the form of a lake or pond. Water expands the boundaries of space to make a garden look infinite. The surface is broken up with dikes, bridges, islands and pond-side pavilions. The water is intended to make a soft sound like relaxing music played on a traditional Chinese instrument. Water also expands the space visually through reflections of the sky and nearby surroundings. It is a symbol of communication in a country with many waterways on which trade and news have traveled for thousands of years.

At the Summer Palace, Kunming Lake, which existed in some form for more than 3,500 years, occupies about 75 percent of the garden. A seventeen-arch rainbow bridge stretches between the east bank and South Lake Island. It is common for a Chinese garden to have an island, a reference to the mythical Isle of the Immortals in the ocean. Kunming Lake also was a flood control project to prevent Beijing from flooding during the rainy season.

Kunming Lake with Longevity Hall behind it.

The Seventeen-Arch Bridge.

Jade Belt Bridge.

Long Corridor

Chinese gardens are not intended to be seen all at once but to unfold, with one beautiful scene after another as one walks through them. Covered corridors from which to view the scenes are a common feature. The 728-meter Long Corridor at the Summer Palace is the longest in China, and has more than 14,000 paintings of historical events and legends on its crossbeams. It is only one of a number of corridors at the Summer Palace with such artwork.

One of the tens of thousands of paintings on the covered corridors.

Longevity Hill and South Lake Island

All Chinese gardens have rocks, from a simple one to an entire mountain. Large gardens have a mountain with pavilions or temples on them. Longevity Hill at the Summer Palace actually is part of the Yanshan Mountains. The tower on the hill is the Tower of Buddhist Incense. The entire complex of buildings on the hill is a microcosm of Buddhism, with a group of buildings modeled on the Song Dynasty-era Hangzhou Fayun Temple, a section of Tibetan Buddhist buildings called the Four Great Regions, and other buildings significant to Buddhism. One section, called Through the Wonderland, supposedly was built after Qianlong dreamed that an old man with a white beard and two maids showed him a painted scroll depicting pavilions and towers. Qianlong entered the scroll, toured the buildings and later had the garden area built like it, according to the legend. The Qing emperors were Buddhist and Cixi presided over Buddhist rituals and celebrations.

Longevity Hill with its collection of Buddhist buildings, a number of them based on famous Buddhist sites elsewhere in China.

Roofs of buildings on Longevity Hill.

The Tibetan Buddhist area called the Four Great Regions on Longevity Hill.

Marble boat

A pavilion built to look like a boat is a common feature of many Chinese gardens. It was popular for elites to enjoy nature seated on the stationary structure. The two-story Marble Boat was built in 1755 in the reign of Qianlong, apparently on the site of a Ming-dynasty temple. The boat had a stone base that supported a wooden structure. Burned by Anglo-French forces in 1860, it was restored on Cixi’s orders with some Western-style architectural features.

The Marble Boat.

Suzhou Market Street

It was common for the Qing emperors to create market streets in their gardens with shops where members of the court could “pretend-shop." The shops were manned by court eunuchs. The version of the market street at the Summer Palace was rebuilt in the 1980s-1990s.

A Man walking by a tea sign at Suzhou Market Street.

Borrowed scenery

Chinese gardeners try to “borrow scenery,” (jiejing), incorporating surrounding scenery into the garden views by blending the near foliage with the distant scenes visually. Here, the borrowed scenery is the Yanshan Mountains.

The Yanshan Mountains are the Summer Palace's "borrowed scenery.

Plants and flowers

The Summer Palace is a traditional area to view flowering trees, especially plum blossoms, in the spring. Plums are one of the three traditional friends of winter, along with pine and bamboo. They blossom early, representing endurance and faithfulness.

The Summer Palace has many skillfully pruned ornamental trees and lotus ponds.

Skilled gardeners tend the plants at the Summer Palace, many of which are flowering.

Check out these related items

Ancient Silk Road Meets High Tech

The International Dunhuang Project digitizes old documents, caves and artifacts to enable global study of Central Asian history.

China’s Walled Cities

Only scattered remnants survive of the many walled cities that once defined the Chinese empire.

Islam in China

Muslims in China are a diverse religious and cultural group with a tumultuous history who take various sides in political disputes.

Treasure Room and Two Palaces

In the French palace at Fontainebleau is a treasure room of dazzling artifacts taken by the French army from a palace in Beijing.

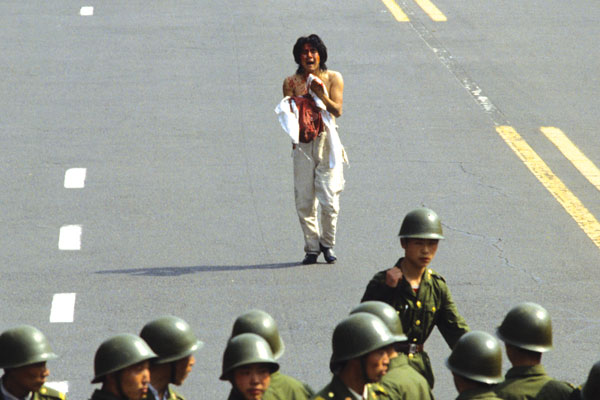

Thirty Years Since Tiananmen

Thirty years ago, students staged pro-democracy protests on Tiananmen Square that shook China's Communist government.

Tiananmen Square

China's Oct. 1 celebration of 70 years of Communist rule centers on Tiananmen Square, one of the world’s most controversial places.