China’s Walled Cities

Photos by Forrest Anderson and historical and other photos in the public domain.

As defensive wall building has come to the fore in U.S. government policy for possibly the first time since the 19th century building of western forts, it is interesting to consider the long history of walls in its superpower counterpart - China.

Visitors to China today are unlikely to see many massive fortifications unless they visit the Great Wall. However, amidst the hodge podge of glitzy high rises, nondescript apartment buildings and traffic congestion that makes up today’s Chinese cities are traces of walls that once made urban cities into huge fortresses. These magnificent structures were intended to protect a vast network of administrative and military centers that linked together the world’s largest empire.

Children playing near a section of Beijing's old city walls.

Today, what remains of a system that reached back thousands of years are for the most part a few short sections of wall, token gates preserved as monuments and names on subway and bus stops close to where city gates and corner towers once stood. Aerial views of some cities, such as Beijing, still show the outlines of the old walls in the form of roads that were built on the paths of city walls after they were torn down.

Five hundred years ago at the beginning of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), China had more than 4,000 walled cities. Others were built in other Asian nations within the Chinese sphere. The huge fortifications represented an enduring imperial system. Chinese cities were built not primarily as trade centers but on the orders of the central government as national, provincial and local administrative centers. The cities housed government officials and armed forces whose job was to protect the empire and its people from rebellions, foreign invasion, natural disasters and famine. The position of cities within the government hierarchy was reflected in city walls’ varying heights, parameters and defenses, with provincial capital walls larger and local city walls smaller, simpler and often more crudely built.

More walled cities existed in northern and northwestern China, a legacy of the long history of warfare with nomadic tribes along the northern edge of China, than in southern China.

The practice of ringing cities in protective walls ebbed and flowed throughout Chinese history and reflected the policies and strength of the particular imperial dynasty that was in power at any given time. By the end of the Ming dynasty, which also built the Great Wall to keep out northern invaders, only about 1,400 walled cities were still standing. The others had been dismantled during peacetime and their materials carried off to build other structures. During the subsequent Qing dynasty (1644-1912), when China was largely at peace and northern non-Chinese territory was absorbed into the Qing empire, wall building fell out of vogue. Many city walls fell into disuse and were dismantled by the 17th century.

The idea of walled cities is so associated with Chinese cities that the same Chinese word, “cheng” is used for both city and wall. The enclosures, located in key areas where trade routes or rich resources needed to be protected, bespoke of imperial authority and order. The walls were made of tons of tamped earth, often faced with brick on at least the outer side and topped with stone. Grand gates in the walls were opened during the daytime to allow people to pass in and out, but were closed at night. On the gates and at corners of the walls were multi-storey wooden towers painted in bright colors and elaborately carved, lending an air of imperial magnificence described in writings by awed travelers.

Well into the latter half of the 20th century, vestiges of many city walls remained. City, town and village walls were maintained and some new ones built as China experienced civil strife and warfare repeatedly during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The history of conflict during those centuries includes famous sieges of walled cities with accompanying famine, cannibalism and slaughters of local citizens after the walls were breached. More common were deals cut with besieging armies to spare cities’ populations in exchange for the gates being opened. Sometimes the aggressors honored those agreements and other times, they systematically massacred the hapless inhabitants. Occasionally, sieges failed because a city’s walled parameters were so large the citizens could plant and harvest enough crops inside the walls to have food, while the besiegers outside ran short of food.

An old photo of Beijing's city wall and a gate.

The walls had peacetime functions as well. They were part of a system that controlled the empire’s population. Major walled cities had night curfews during which watchmen patrolled streets. Only those dealing with medical emergencies and officials with passes could break curfew without punishment.

Walled cities were sited on lowlands, unlike the European custom of locating castles in high ground. Water supplies were guaranteed by locating cities along river banks, and access to a river facilitated water transport of goods to supply a city. Walls sometimes also doubled as dykes to protect a city from flooding, the walls following river banks rather than being square or rectangular. Moats around the cities and canals provided a drainage system during the rainy summer season.

The northern walls of some cities in China’s north were screens against cold winds and sandstorms that piled up against the walls until they periodically had to be removed. In some cities, local people could scale a northern city wall by walking up the sand.

Walled cities provided the empire with a steady flow of taxes, government services and, with their civil service examination halls, government personnel. The city structures were fairly uniform from place to place because they were considered part of a central system, not just entities standing on their own. Government units inside the cities administered not only within the walls but the areas around the cities. On the mountains around the cities were well-guarded passes and fortifications that the cities also administered. The rural people around cities provided food and taxes in return for protection.

Surprisingly little is recorded in Chinese records about the hundreds of walls around cities, towns and villages, probably because they were built by illiterate artisans and laborers who left no record. A classic work from the Zhou dynasty (509-221 BC) included a description of a walled city as square, with three gates on each side, but few cities were close to this configuration and it is likely that it was only a simplified example that didn’t necessarily mean that a wall should be square. Square or rectangular walls were more common in northern China, probably because the flat northern plains made it easier to lay out a regular shape there than in central and southern China, where many city walls wound along ridges or streams. One of the puzzles of local gazetteers in which maps of walled cities were included is that some cities were portrayed as having even shapes when the actual walls were irregular. Obviously, the map makers intended for the maps to show more about the cities’ system than geography.

The use of high tamped-earth walls was an ancient practice long before China became a unified empire in the third century B.C. Tamped-earth walls are common finds in archaeological digs. High tamped-earth walls also were used to mark borders between kingdoms. Tamped-earth walls still are built in the Chinese countryside. The Chinese also exported the practice, which can be seen at sites in Japan. The walls are made by piling freshly dug earth, often from a trench that will become the wall’s moat, and other materials into a framework and pounding it firmly down with a rammer with a heavy stone or wooden block on its end. Once the soil is compacted, a layer of bamboo or stone rubble is spread on top to strengthen it. Then the process is repeated with the framework repositioned higher up and other layers added and tamped down. This continues until the wall reaches the planned height. In some periods, straw mats were added on the surface of walls to stabilize them. In imperial capitals and major cities, especially during the Ming dynasty, large bricks faced the walls. Walls typically were wider at the base than at the top.

This display at the Heijo museum in Nara, Japan, the site of an ancient walled Japanese capital built on the model of the Chinese walled city of Chang'an, shows how tamped-earth walls were made. On the left is a standard tamping block and on the right is an edge tamping block. The sample piece of tamped-earth wall in the center feels as hard as a concrete block.

Tamped-earth walls at Horyuji Temple in Nara, Japan. The early Japanese adoption of the Chinese tamped-earth wall technology made such walls an iconic element in Japanese architecture along with the tradition of walled fortresses such as the much later built Osaka Castle. Photo by Forrest Anderson.

Even some smaller Chinese towns had massive walls. The best extant example is Pingyao in northern China, once a financial center that still retains its city wall largely intact.

The restored walls around Pingyao, China.

City walls decayed slowly as plants took root in the walls and created channels into which water could run. They took on a charming look of antiquity as they aged. Occasionally, local officials repaired them, so that many city walls looked patched from repairs made at different times. Sometimes a wealthy official would be ordered to repair a section at his expense as community service punishment for accepting a bribe or another infraction. In some cases, people ordered to repair the walls left a record of the date on bricks they installed.

Decaying tamped-earth walls were an irresistible temptation to local farmers, who often borrowed soil from old walls to build terraces and level fields for farming. The grasses and roots mixed into the walls enriched the soil, making it good fertilizer for their intensely cultivated fields.

The walls were part of an entire architectural system that typically included city gates and avenues connecting to them, a civil service examination hall, a palace or local administrative halls, a Confucian temple, a temple to the city god and other temples. Sometimes, as in the case of imperial capitals, there were concentric walls, the outer wall encompassing the city, a middle wall encompassing government administration buildings and housing for nobility and government officials and a third inner wall encompassing the palace complex. In some cases, additional walled sections were added as the population of a city grew in a particular direction.

As late as the 1920s and 1930s, some walled cities provided added security from bandits and roaming armies in a period of civil unrest.

Most city walls had at least four gates, each opening toward one of the cardinal directions and connected to avenues that ran through the cities. Larger cities had many more. The city of Kaifeng, once the imperial capital for the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127), had 13 gates.

The gates had elegant classical names that sometimes were changed when a new dynasty took over, and each gate was symbolic – the east gates representing spring and the rising of the sun; the south representing summer; the west autumn and death as the ancestors used it to travel to the Western Paradise after dying; and the north winter and calamity, since invaders and winter came from north of China. In northern China, the north gate was usually kept closed to prevent cold winds from entering the city. Chinese armies also typically rode to war to the north.

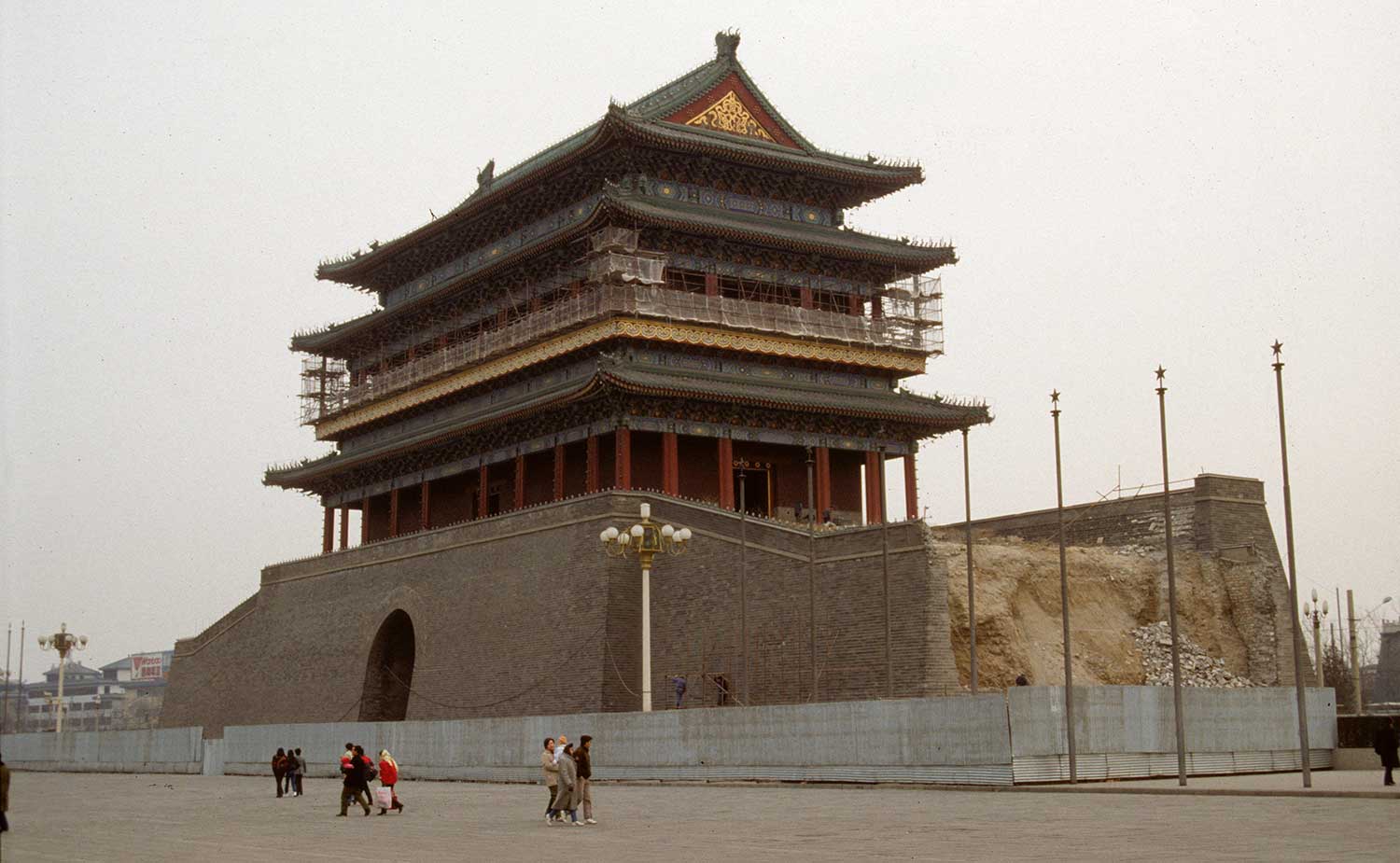

Some gates were simple arched tunnels in the city wall, others were for the flow of water into or out of a city and the most elaborate had two or more gates lined up behind each other with a courtyard between them for defensive purposes. Barbicans stuck outward from the walls in a semicircle or rectangle in these cases. These gate systems were called wengcheng, meaning an urn-shaped wall, probably part of a traditional tendency to refer to architectural structures with the same terms as ceramics.

Historic photo of Anding Gate's barbican, Beijing.

Guards who maintained the gates exercised a position of authority and expected as the price of passage to be given eggs, vegetables or other produce by those entering the city to sell food to the urban populace. The gates were closed at night, with only those with a wooden pass allowed to pass through them. However, during the day, market stalls and people thronged through and around the gates conducting business. The areas around gates typically became market and commercial districts. Even today, this tendancy remains in some places in both China and Japan where ancient gate areas now have busy subway stations that connect to large commercial centers and malls.

Most cities had multiple areas of activities around gates, temples, markets and government offices and larger cities had separate districts for selling different commodities, such as tea, medicine, books, cloth or ceramics. There were sections for services such as tailoring, blacksmithing, coopering or pawn broking. Each shop had a long narrow signboard hung in front to advertise the kind of goods sold. Street names often reflected what was sold on a street, and some of those names remain today. Hawkers also went door to door peddling goods and services to individual households along the narrow lanes.

Gate towers and corner towers atop the gates were usually at least two storey-high wooden structures with clay roof tiles, and were elaborately carved and painted. They served as guards’ vantage points, barracks and armories. Gates also had hidden underground weapons arsenals. Defense was coordinated from the gate and corner towers.

Major streets were aligned to reach from gate to gate, often crisscrossing each other. A drum tower with drums to mark the passage of time was placed on the center intersection or along the north-south axis, sending at regular intervals drum beats to remind citizens that the emperor controlled not just the space they lived in, but also the time.

In many cases, a main thoroughfare ran east to west, but there was no single road from the north to the south wall. Other cities had a thoroughfare running north to south, but no continuous east-west one. Government administrative offices were generally near the north-south thoroughfare.

Chinese cities were mainly one story except for drum and bell towers so the walls were by far the highest structures. Residential lanes mostly ran east to west, with walls down either side behind which were walled courtyard houses. Settlement often spread outside the walls near the main gates on major roads leading into a city. When such a district became economically important, walls would be built around it that connected to the main city walls.

In some cities, there were separate enclaves for different ethnic or religious groups of residents. This type of segregation was mandatory in more than 30 cities during the Qing dynasty, when the ruling Manchus lived in separate central enclaves away from the native Chinese. The Chinese bitterly resented this segregation, which originally had forced them out of the choicest areas in some cities, and as the Qing dynasty crumbled, rebels attacked Manchu enclaves.

Many cities had open areas beyond built-out areas, with ponds, canals and cultivated land that provided gardens for high level officials and gentry to enjoy.

The disintegration of the Chinese imperial system and subsequent weakness of the government from 1912-1949 were accompanied by the gradual decay and demolition of city walls. As China began its tortuous climb toward modernity in the 19th century, the walls and their towers became ever less effective against invading threats. Advances in weaponry by the early 20th century rendered the wooden towers atop the walls vulnerable and obsolete. City walls fell into disrepair as their usefulness declined along with the empire. Chinese reformers concluded that what China needed was not obstructive walls but open commerce and modern transportation. City walls were first breached to build railroads and then highways and then torn down all together to build the modern ring roads of today’s Chinese cities. As the imperial dynasty was overthrown, some of its successors such as Mao Zedong despised the walls as symbols of an old feudal past they had sought to destroy. Under the Communist government that took power in 1949, walls were systematically demolished.

A train running past one of Beijing's city gates, which appears isolated and truncated because the wall that once connected to it was destroyed to allow rail and road traffic in the city.

Today’s cities are largely wall-less. With the exception of Pingyao, few have more than scattered remnants left of their walls and terms such as bao (fortress) as part of local place names.

Beijiing's magnificent walls that once rose from the North China Plain are gone.

Wall building was associated with defense and tumultuous times rather than with strength. Thus it was neglected when the empire was prosperous and secure and revived when it was on the defensive. It is in the former state that China is in today, the country’s strength largely dependent on its robust commercial networks, both at home and abroad, and its aggressive diplomacy.

Nonetheless, the roots of the old defensive strategies remain engrained in its governing psychology. China’s people physically can move about more freely than they have perhaps in their entire history, but they are closely monitored with invisible walls of cybersecurity, censorship, a massive police and security force, and a government hierarchy that still draws on a national, provincial and local organization similar to that which once determined the size and magnificence of walled administrative cities and towns.

China continues to destroy old neighborhoods in its once-walled cities, but there is a strong current of national nostalgia for the beautiful walls that once characterized imperial China, especially for Beijing’s walls. A 100-metre section of Beijing’s wall has been rediscovered and rebuilt, partly with donations of 60,000 bricks by people who collected them when the city walls were demolished in the 1960s. Nanjing still has part of its walls, which were saved from destruction after they protected the city from a flood, and Pingyao’s walls survive intact after local preservation efforts convinced higher levels to back off on a plan to destroy them.

In imperial China, the emperor was considered the Son of Heaven. He lived in a walled city that was a clone of a heavenly city in which the Heavenly Emperor ruled with the help of divine officials and military. China’s network of walled cities, emanating out from the imperial capital via royal roads, represented much more than a defense and government system. It represented the Chinese mapping of their role and location in the cosmos, what distinguished them from the “barbarians” they believed lived outside their borders. Many Chinese feel the deep loss of the visual and functional architecture that once defined their world, as today’s Chinese cities become largely indistinguishable from cities elsewhere. Some of these voices have begun to restore neighborhoods and sections of city walls as tourist attractions. These uncoordinated efforts, however, say little about the system that once defined what the Chinese were.

Even as China’s city walls have disappeared, technology has enabled archaeologists to detect outlines of old city walls from satellite photographs and to uncover the remains of ancient city walls that had been previously unknown. They have pushed the history of city wall building in China back to 6000 years ago and beyond.

Tamped-earth walls also have become a commonly used design motif in both Chinese and Japanese modern architecture in an often highly modernized and stylized form.

Related photos:

Check out these related items

The Summer Palace

The Summer Palace, the most famous and heartbreaking of China's glorious imperial gardens, highlights dilemmas in the nation’s past.

Treasure Room and Two Palaces

In the French palace at Fontainebleau is a treasure room of dazzling artifacts taken by the French army from a palace in Beijing.

Ancient Silk Road Meets High Tech

The International Dunhuang Project digitizes old documents, caves and artifacts to enable global study of Central Asian history.

Tiananmen Square

China's Oct. 1 celebration of 70 years of Communist rule centers on Tiananmen Square, one of the world’s most controversial places.

Chinese Moments Published

Chinese Moments, our photo book on China in the turbulent 1980s and 1990s, has been published as an ebook and paperback.

Islam in China

Muslims in China are a diverse religious and cultural group with a tumultuous history who take various sides in political disputes.