Tiananmen Square

Photos by Forrest Anderson and historic photos that are in the public domain. Illustrations by Donna Rouviere Anderson.

As China ramps up for the 70th anniversary of Communist rule on Oct. 1, Tiananmen Square in Beijing has become the center of preparations for large-scale commemorative events. The milestone marks China becoming the longest-lived Communist-ruled country, passing the former Soviet Union’s 69 years of rule.

The event will be commemorated with a military parade, speeches, fireworks and other events aimed at commemorating the country’s political history and its status as one of the world’s largest economies and a major international power. The event will come as China and the United States face off in a trade war and protesters in Hong Kong have challenged a now-withdrawn bill that would have allowed criminal suspects be extradited to mainland China for trial.

Celebrations will be held across the country, but will center on the square, the symbolic heart of China. At 109 acres the world’s third largest, the square has long been known in the West mainly for the 1989 Tiananmen protests and army crackdown. However, the square area has been at the center of China’s history for some 800 years. Thousands of events aimed at either demonstrating the power of the Chinese empire or challenging it have been staged in and around the square.

The military parade that will march past Tiananmen Gate on the north side of the square is expected to be the largest in the nation’s history with thousands of troops and displays of China’s most advanced weaponry. Army General Cai Zhijun said the parade was not a sign of aggression and the army is “committed to safeguarding world peace and regional stability.”

“At the same time, we have the determination and ability to resolutely safeguard our national sovereignty, security and developed interests,” he said.

Security has been ramped up around the square and tightened across China, especially in politically sensitive areas such as western China’s Xinjiang province and Guangdong, which neighbors on Hong Kong. It has been tightened on China's already censored Internet to the point where it even annoyed the editor of the state-controlled Global Times, Hu Xijin, who usually is an enthusiastic supporter of hard-line policies, because it interfered with his journalists' attempts to access the Internet. Hu wrote on social media: “This country is not fragile. I suggest society should have greater access to the outside internet, which will benefit the strength and maturity of China’s public opinion, scientific research and external communications, as well as China’s national interests.”

Parade rehearsals indicate that the parade will include spy and attack drones, advanced missiles including one that can carry up to 10 nuclear warheads and hit targets on the U.S. mainland, a new strategic bomber, and a lightweight battle tank. In a rehearsal last weekend, aircraft flew in formation to form the number 70. Comments on the Internet noted that the display was a far cry from the Oct. 1, 1949 display that marked the founding of Communist China, when a few airplanes flew over the square twice to look more impressive. China’s top leader, Xi Jinping, is expected to make a speech and a traditional spectacular fireworks display is planned. Parades will be held in other cities, although the annual fireworks display in Hong Kong has been canceled.

The Global Times noted that “At this year's anniversary, China's national strength has reached an unprecedented high and yet it also faces extraordinary challenges at the same time. Celebrating National Day well is objectively a mobilization of national cohesion.” The paper warned that many uphill battles await the country.

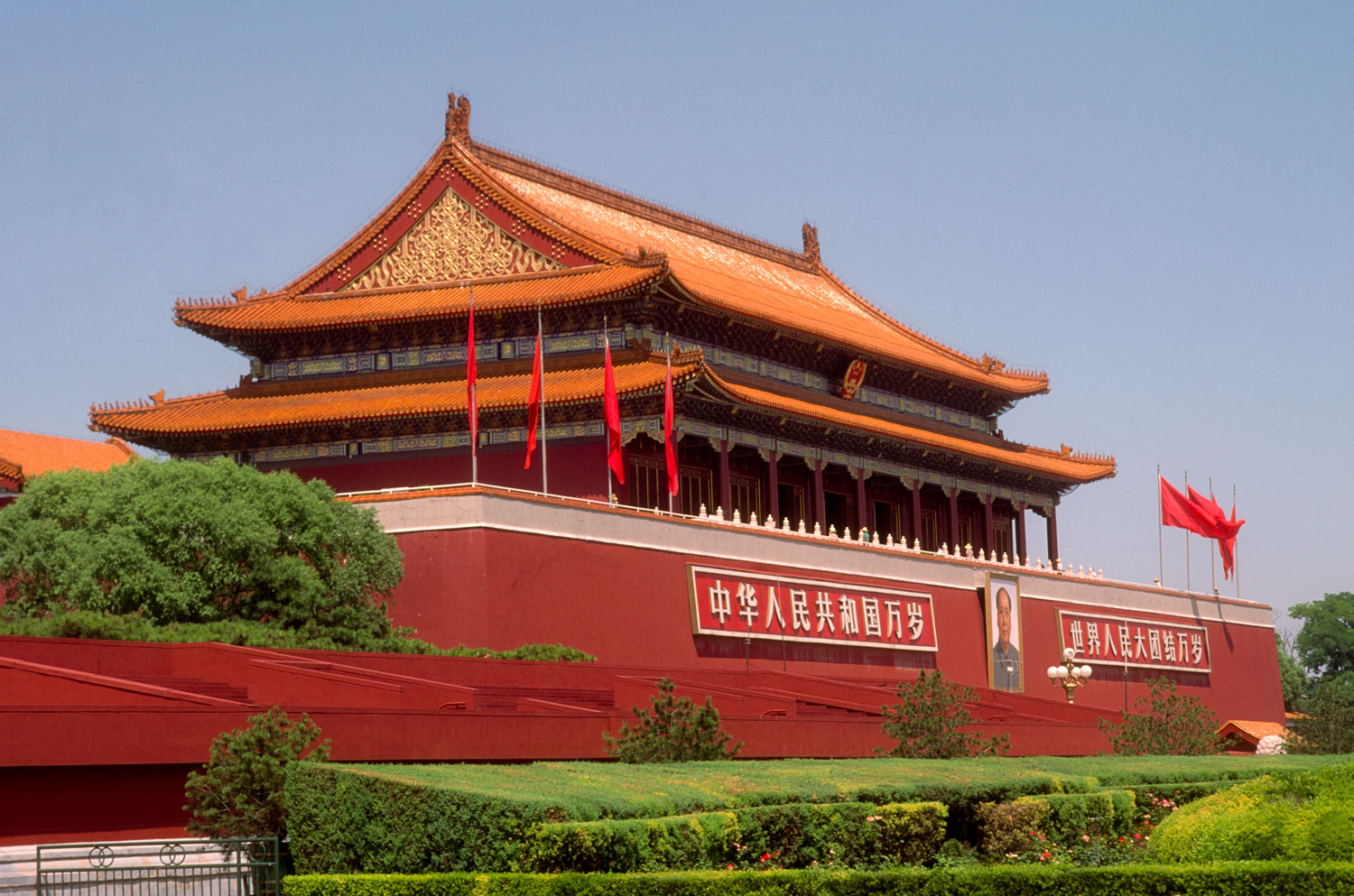

The vast concrete Tiananmen Square where the celebration will occur is surrounded on all sides by China’s history. To the north, through Tiananmen Gate that gives the square its name, is the golden-tiled Forbidden City. Today China’s premier museum, the Forbidden City was the palace of China’s emperors from the early 1400s to 1912. The great central axis running through the Forbidden City and south through what is today the square was once the northernmost section of the Imperial Way, a royal route that ran south through the Chinese empire. The emperor and his entourage traveled this route on grand inspection tours and his couriers and officials moved along it to conduct imperial business.

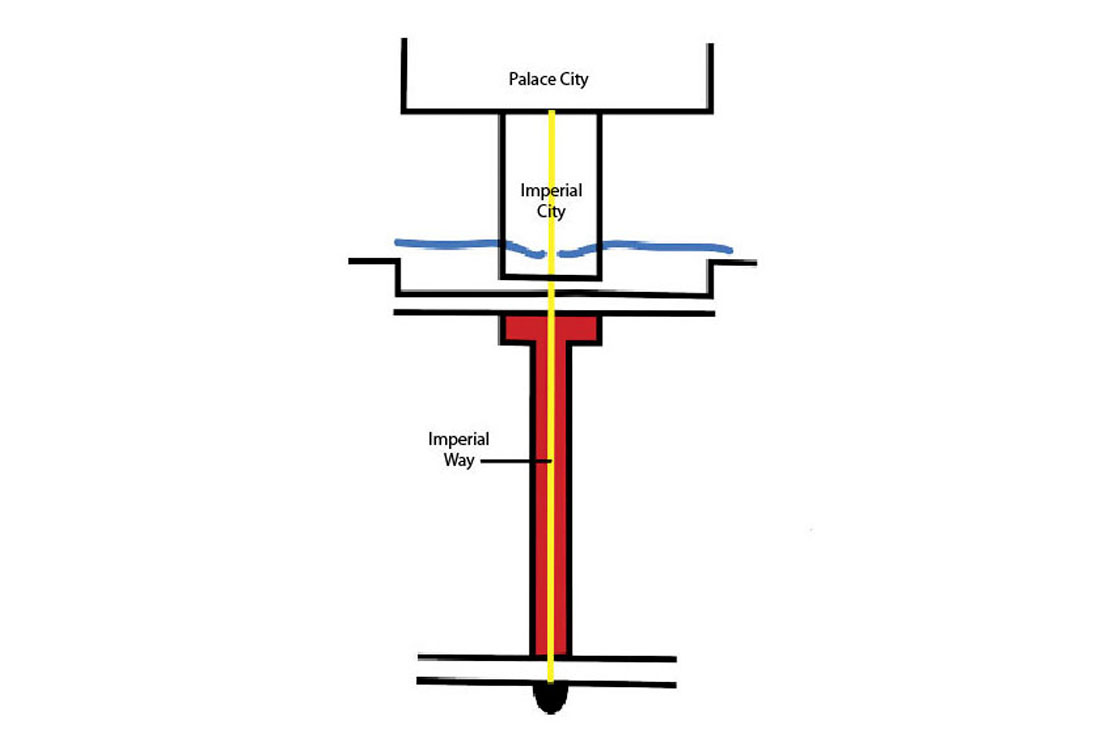

In imperial times, the walled Forbidden City was surrounded by a larger walled compound called the Imperial City and then a third ring of massive city walls and a partial fourth ring of walls on the south. Beijing was a huge heavily defended fortress. Today’s square was once a corridor called the Corridor of a Thousand Steps that connected the palace to the main city gates and thus to China’s people. This notion of a corridor stretching south from the palace along a central axis to the capital’s gate existed as far back as the 3rd century and was part of a number of ancient Chinese capitals as well as being imitated as far away as Japan and Korea.

This diagram shows in yellow the imperial way, and in red the T-shaped corridor south of Tiananmen Gate that now is the Tiananmen Square area.

The Corridor of a Thousand Steps was later expanded to create Tiananmen Square. This 1990s photo shows the square before high-rise buildings were built on its southern side. This view is from the balcony on Tiananmen Gate. On the left is the Museum of National History and on the right is the Great Hall of the People. Down the middle on the central axis is the Monument to the People's Heroes and the Mao Memorial Hall.

Only trusted officials were allowed an audience with the emperor, whose splendor unfolded gradually as the officials proceeded along the central axis through multiple courtyards to the throne hall in the Forbidden City. Smaller versions of this model were created in walled provincial fortress cities and smaller walled towns, creating a hierarchy of fortresses linked by roads nationwide. This system defined the Chinese empire and became a fundamental element of Chinese culture.

In Chinese ideology, heaven and earth met at the emperor’s throne. The emperor had a pact with heaven to rule so that the nation prospered and was at peace. The name Tiananmen, “Gate of Heavenly Peace,” meant that the emperor was responsible to heaven for keeping the empire at peace. Should he fail, the people were implicitly justified in rebelling, not to rule China themselves but to rally behind a new emperor who would restore the empire’s power and prosperity.

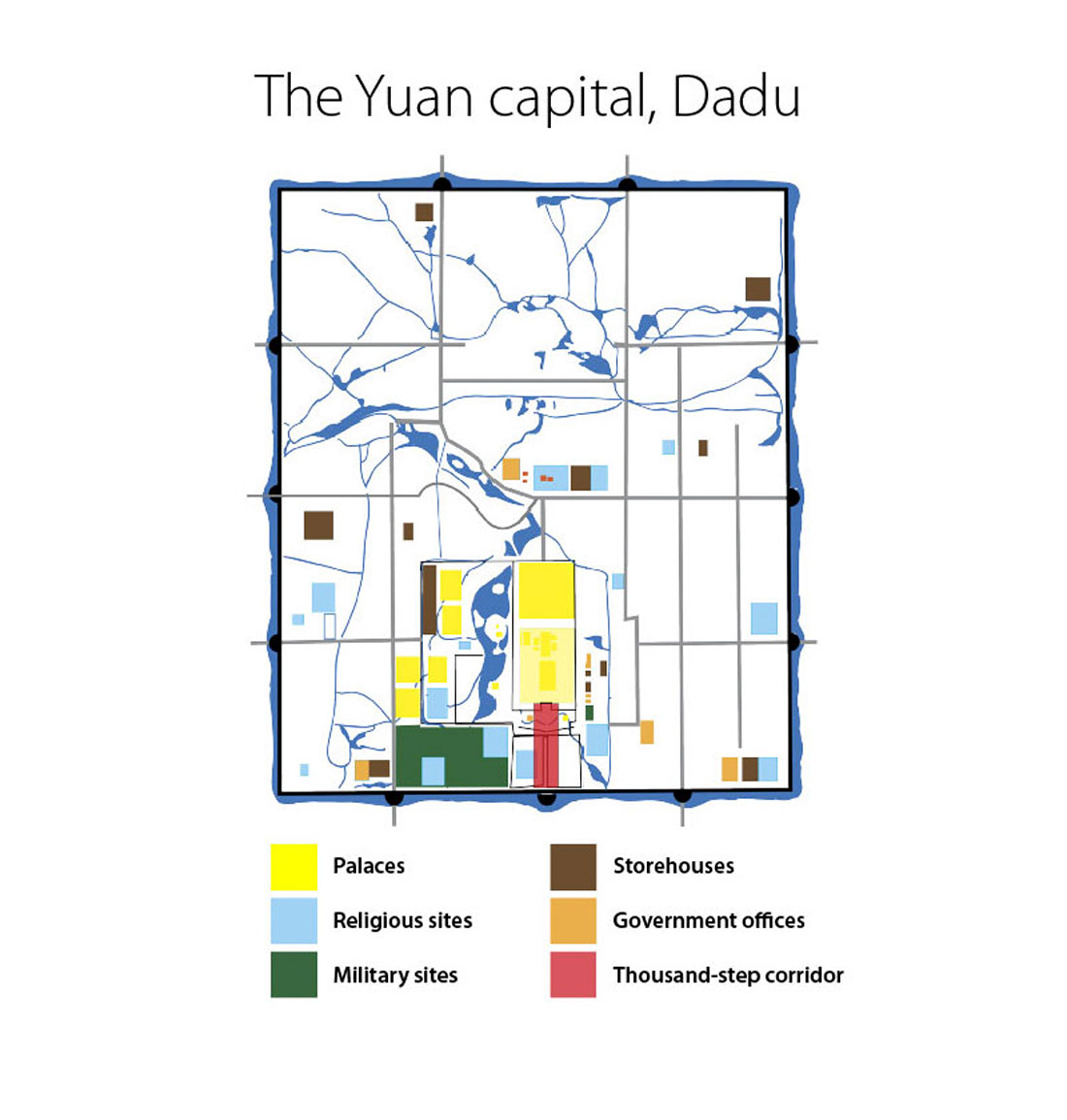

Beijing’s origins as a regional military fortress reached as far back as the emperor Qin Shi Huang (259-210 BC) of terracotta warrior fame. The city evolved into a capital when northern Chinese tribes conquered parts of northern China and built Chinese-style capitals at Beijing, starting in 1127. Beijing’s current north-south axis along which Tiananmen Square is situated was part of a grand capital built by Genghis Khan’s descendants after his army swept out of Mongolia to conquer China and create what they called the Yuan dynasty. The axis of the capital, which they called Dadu, was aligned with the Mongolians’ summer capital in their homeland. Today’s Tiananmen Gate is on this axis and is believed to be roughly where Dadu's main city gate was located.

This diagram shows in red the Thousand-Step Corridor of the Yuan capital. The main south gate of this capital was roughly where Tiananmen Gate is located today.

When Chinese rebels wrenched control from the Mongolians and established the Ming dynasty, they established their capital briefly in the city of Nanjing. After the Ming founder’s fourth son, Yongle, seized the throne, he moved the capital to his power base, Beijing, and built a new city on the old Mongolian capital’s north-south axis but slightly to the south. The footprint of the Ming capital was retained into modern times. On either side of the T-shaped corridor south of Tiananmen Gate, the Ming built ministries that transmitted the emperor’s decrees into practical initiatives. The ministries’ positioning was a visual representation of the two forces – cultural and military strength – that still hold China together today. On the east were ministries responsible for civil, peaceful functions – the imperial clan, officials, revenue, manufacturing, rites and medicine. On the west were security offices – the army, imperial guard, police and justice. “Those on the east govern our lives. Those on the west govern our death,” a Chinese saying went. The two sides were an architectural manifestation of the dynastic system’s emphasis on order, ritual, stability, culture and family combined with the dark side of executions, forced labor, torture and brutality. The corridor that cut through between the civil and military offices symbolized the emperor’s ability to balance both sides. Today, senior Communist Party leaders take on a similar balancing role.

The main city gates to the south of Tiananmen Square, Zhengyang Gate and Qianmen Gate, are still extant, while a ceremonial gate called Da Ming Gate has been replaced by a large memorial hall. South of Da Ming Gate was an area called Chessboard Street that connected the security offices with the civilian ones. This became a meeting place for the imperial, public and economic sectors of society. It was cleared of people and decorated with banners when the emperor and his entourage exited or when an annual Grand State Assembly was held. Today, a similar clearing of the square or part of it occurs when welcoming ceremonies for foreign dignitaries or official celebrations are held.

Beijing’s greatest market, where merchants traded with court officials for goods from all over the empire and beyond, was around Zhengyang Gate on the south end of the square. Goods flowed into this area, creating the Qianmen business district that still thrives today. The terminus of rice shipments from the south on the Grand Canal was outside Zhengyang Gate. Beijing was fed by more than 10,000 rice ships that sailed along the canal. Zhengyang Gate was connected with Qianmen Gate by a U-shaped wall or barbican.

Northeast and northwest of Tiananmen Gate are the Ancestral Temple and Altar of Land and Grain, where the emperor performed rituals to ensure that heaven and his ancestors smiled on the empire. In imperial times, military displays did not occur in the Tiananmen area, but at the city’s north gate through which armies exited for war.

Some 200,000 people, many convicts who worked in chains, were conscripted to build Yongle’s Beijing.

On the north side of Tiananmen Gate, officials were flogged when the emperor was angry with them, and they sometimes died from the beatings. On either side of the gate are stone pillars called Huabiao. Yongle allowed senior officials to deposit criticisms at the pillars in the form of personal memorials. If he was displeased, he could order an official beaten or killed. It is to this tradition that modern dissidents sometimes have referred in public protests in front of the gate. Like the officials before them, protesters are likely to be arrested and beaten.

Down the center of the corridor ran a stone path used only by the emperor, while officials used walkways on either side. The emperor’s path is no longer marked on the square but its main axis is implied because structures are centered on it or aligned facing it. Inside the Forbidden City, the stone path still exists.

The subsequent Qing dynasty, northern non-Chinese conquerors, retained the Ming Forbidden City’s basic layout. A number of Qing emperors preferred to live in imperial gardens on the city’s outskirts, but kept the Tiananmen and Forbidden City area for state functions and rituals that reinforced their status as China’s emperors. In the declining years of their rule, the area around the corridor became rundown. Much of what we know about the Tiananmen area in Imperial times is from the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). Court painters did artwork that included the square area and it was photographed beginning in the mid-19th century.

During the Qing dynasty, officials entered the palace through Tiananmen daily to report to the emperor in a lavish ceremony with drummers, lashing of whips, clouds of incense smoke, and ceremonial music.

When the Qing emperors left Beijing via the corridor to inspect the empire, as many as three thousand people – guards, eunuchs, officials, palace ladies, maids, princes, cooks, horse tenders and soldiers – accompanied them. Court painters commemorated the inspection tours on large scrolls. The emperors met with local officials in various regions, inspected dikes and other projects, discussed local conditions, talked to scholars, remitted taxes and pardoned criminals. Xi Jinping, who travels frequently in China, conducts some of the same kinds of business on inspection tours.

A vast number of people lived or worked around the square. The emperors had many wives, children, grandchildren and relatives. To serve them, the Imperial Household Department had up to 2,000 eunuchs and between 200 and 300 ladies-in-waiting and maids. Many skilled artisans also worked in palace workshops and hundreds of soldiers and police guarded the palace. Every morning, peasants lined up south of Zhengyang Gate for guards to open it so they could bring in carts of produce to feed the city. Palace eunuchs demanded a portion of the goods before the peasants could bring in the food.

Foreign envoys went from Zhengyang Gate to Tiananmen Gate to enter the Forbidden City. On rare occasions, vanquished enemies led by silken cords around their necks were presented to the throne before execution.

When a new emperor was enthroned or a royal heir was born, the event was announced in an elaborate ceremony that included reading the edict from Tiananmen Gate as officials listened and kowtowed. The final imperial edict issued there was on February 12, 1912, when the last Qing emperor abdicated and China became a republic.

After Western armies occupied the city in 1860 to force China to open to domestic trade, they established foreign embassy compounds called the Legation Quarter southeast of the square. Western style buildings such as embassies, banks, office buildings, hospitals, clubs, hotels and foreign military garrisons rose on the southeast and southwest sides of the square. An old bank building with a clock tower on the square’s west side and the Old Beijing Railway Station on the southeast corner still remain.

As foreigners dominated Chinese ports in the declining years of the Qing Dynasty, a backlash of anti-foreign and anti-Christian sentiment swept over China. A violent movement called the Boxer Rebellion attacked Christians, burning Christian churches in Beijing. Diplomats called for military assistance from their countries and foreign troops marched from the eastern city of Tianjin while foreigners gathered for safety in the Legation Quarter. Terrified local residents fled. The Eastern Cathedral with many Chinese Catholics inside it as well as part of the Qianmen area and Zhengyang Gate were burned. There were dozens of deaths and injuries. The siege ended when 20,000 foreign soldiers arrived in Beijing. The next day the empress dowager and her court fled to Xi’an, the ancient capital to the west. The Boxers retreated and the foreign troops occupied the city until reaching an agreement the next year with the Qing government. The Americans set up camp in the Forbidden City, and priceless art objects were stolen from the palace and other buildings. The Boxer Protocol negotiated in 1901 imposed on China a $333 million indemnity. The conflict shattered the city’s physical infrastructure, and the Beijing that was rebuilt was more modern and foreign, with paved roads, street lighting and telephone wiring. Many local residents detested the controversial rebuilding of Zhengyang Gate with Western-style eyebrows above the openings. Rail tracks breached the city wall, with tracks to the Qianmen area so the Legation Quarter could be evacuated if necessary. In 1902, the Qing court returned to Beijing in a procession that some foreigners photographed.

This historical photograph shows the imperial court returning to the palace along the corridor. The gate in the front is Da Ming Gate, which was renamed Da Qing Gate in the Qing dynasty. To the rear is Tianamen Gate. This entire area is now Tiananmen Square.

Railroad tracks were run around the outside of the city wall. The Old Beijing Railway Station was built in 1906 on the southeast side of the square. The station, main government area, Legation Quarter and main business district all in one area created serious congestion. The barbican wall connecting Qianmen and Zhengyang gates was razed and two broad streets were placed to run past them along the sides of the Tiananmen area.

After the Qing Dynasty fell in 1912, the gate became associated with a series of events as China strove to create a strong government to replace the old imperial order:

- When World War I ended in 1919, about 6,000 people paraded in Beijing, but their joy turned to outrage when the final international treaty supported Japan’s claim to areas of Shandong province previously controlled by the Germans. More than 3,000 students demonstrated against the agreement in front of Tiananmen Gate on May 4, 1919. They marched south along the Corridor of a Thousand Steps and to the Legation Quarter, where guards turned them away. They set fire to the house of a Chinese minister and beat up the Chinese minister to Tokyo and a Japanese journalist. Thirty-two students were arrested. The unrest spread all over China. Three days later, police blocked another protest. Three thousand students were arrested in Beijing, but the Chinese government didn’t sign the treaty. China’s leadership considers the May 4th Movement the precursor of the Chinese revolution that brought the Communists to power.

- Chinese revolutionary Sun Yat-sen died in Beijing in 1925 while there to discuss China’s future. Some 740,000 people paid homage to him at the park northwest of Tiananmen Square, which was later named Zhongshan Park after his Mandarin name. His funeral procession passed through Zhengyang Gate and the Tiananmen area.

- In 1926, the founder of the Chinese Communist Party, Li Dazhao, led a protest of 2,000 people at Tiananmen against the government acquiescing to a Japanese demand that Chinese defenses between Beijing and the sea be removed. When the protesters marched to a cabinet official’s house, guards opened fire and soldiers with bayonets charged into the crowd. At least 50 unarmed protesters were killed and 200 wounded. Warrants were issued for the arrest of Li and other protesters. Li took refuge in the Soviet Embassy in the Legation Quarter. Warlord Zhang Zuolin shortly after took over Beijing and seized Li from the Soviet Embassy. Li and 19 others were executed on April 25, 1927.

A protest on the south end of the Tiananmen Square area in the 1920s.

- During the 1920s, Beijing’s municipal government paved and widened the Avenue of Eternal Peace, the east-west road in front of Tiananmen Gate, and it became the city’s main street.

- The Nationalists rose to power in 1927 and consolidated their control of Beijing. Photographs of the event show throngs of people gathered in the area around Tiananmen to watch. The Nationalists moved the capital to Nanjing where their power base was. In February 1933, the palace art collection of 700,000 works was carted in wheelbarrows through the Tiananmen corridor from the Forbidden City to the Beijing Railway Station and shipped to Nanjing for safe keeping as Japanese invaders moved into northern China. About 20 percent of the collection was taken to Taiwan with the Nationalists in 1949. It remains there, but other parts of the collection were later returned to the Forbidden City.

- A variety of social movements protested in front of Tiananmen Gate under the Nationalists, some of which were later coopted by the Communists. The Nationalists controlled the city until 1937, when the Japanese marched into the city on the Tiananmen corridor. The city reverted to Nationalist control in 1945 after the Japanese were defeated.

At the end of the ensuing civil war that broke out between the Nationalists and the Communists, the Communist 8th Route Army marched south to Beijing in late 1948 as the city prepared for a siege. The city walls were armed with gun emplacements, trenches were dug along the moat, and refugees fled to the city. No one left or entered for fear of conscription into labor by one of the two armies. Only airplanes went in and out, landing on airstrips east of the Forbidden City, at the Legation Quarter or to the south. The Communists gave the city’s Nationalist commander an ultimatum to surrender by 2 p.m. on January 22, 1949 or the Communist Army would forcibly take the city. The commander and his troops left the city on January 31. The first of about 200,000 Communist soldiers marched from the east into Beijing, accompanied by tanks.

On February 3, a grand eight-hour military parade along the Imperial Way toward Tiananmen Gate was staged. The forces carried large portraits of Mao Zedong and his commander, Zhu De. Beijing residents lined the streets applauding the new conquerors. The parade included singing performers, troops, American-made tanks, armored cars, jeeps, heavy artillery, trucks with mounted machine guns and ambulances captured from the Nationalists. At a mass meeting in Tiananmen Square, Chiang Kai-shek was depicted as a turtle with Uncle Sam as his rider.

The Communist Army Beijing, heading north through the Qianmen business area and the main southern gates to the Tiananmen area. Zhengyang Gate is visible at the upper left corner.

On October 1, 1949 at 3 p.m., Mao stood on Tiananmen Gate and announced the founding of the People’s Republic. Mao then launched into a list of government appointments. The 300,000 listeners shouted “Long Live the People’s Republic of China!” and ”Long Live Chairman Mao!” The phrase “long live” literally means “ten thousand years“ and had been used to wish longevity to emperors. Years later, some veteran revolutionaries said they listened with forboding to the crowd shouting words exalting Mao to the status of an emperor.

Mao's 1949 declaration of the founding of the People's Republic of China is depicted in this famous painting, on display in Beijing.

A military parade followed. The Communists had researched parades to make a plan for it. Veteran revolutionary Chen Yi told the organizers, “There is no difficulty in organizing the parade, it is no big deal. We have already won many battles, is it possible that we cannot prepare a military parade well? It’s just about marching, is it not?”

Troops passed in front of the Tiananmen rostrum from east to west as Commander in Chief Zhu De and Marshal Nie Rongzhen reviewed them from a parade car. Troops representing the navy, army artillery, panzer units and cavalry passed by, wielding a variety of weapons. The artillery division had 75mm field guns, 105mm howitzers, 37mm and 75mm anti-aircraft guns. The panzer division had regiments of motorized infantry, armored infantry and tank forces. The cavalry division had three cavalry regiments and a 75 mm field gun battalion drawn by mules. The air force, including a P-51 fighter squadron, a De Havilland Mosquito bomber squad and a PT-19 and L-5 training Squad, moved by last. When the panzer division entered the square, planes flew over in formation. More than 16,000 soldiers, 152 tanks and armored vehicles, more than 200 cars, more than 2,300 war horses and 17 planes participated in the parade, which established the pattern for subsequent Chinese military parades.

The Communists took years to consolidate control of China, but the parade’s symbolic message was that as the Communists controlled the Tiananmen area, so they controlled the empire.

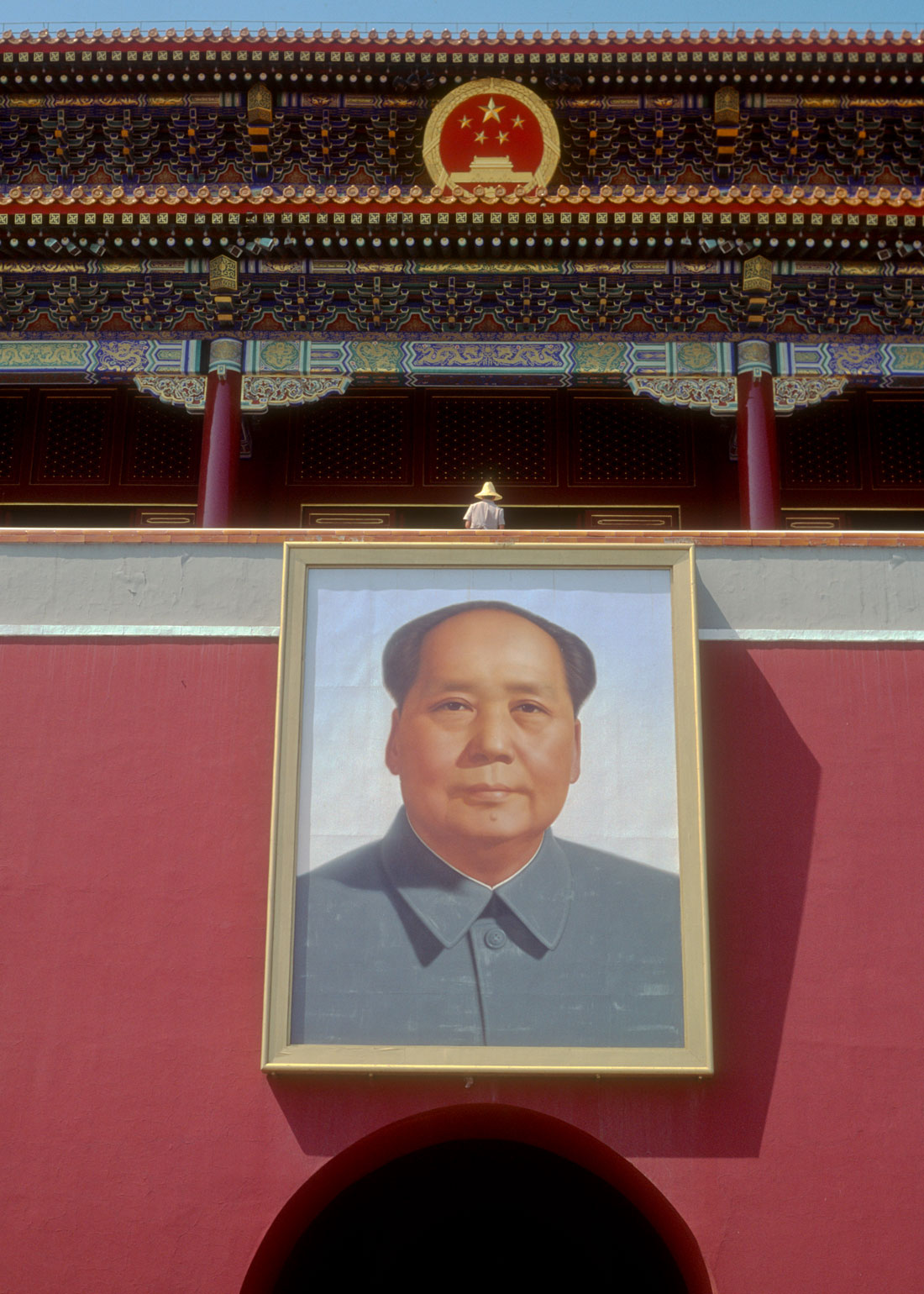

Mao’s portrait in an army cap and two huge slogans were placed on Tiananmen Gate for the founding ceremony. The left slogan read “Long Live the People’s Republic of China” and the right, “Long Live the Central Government of the People.” This was later changed to “Long Live the Union of People in the World.”

Mao’s portrait was not the first to hang on the gate. When Sun Yatsen died, a large portrait of him was carried in the hearse that moved along the Avenue of Eternal Peace to the funeral. His portrait subsequently was hung on Tiananmen Gate, along with written slogans. After the Nationalist army retook Beijing from the Japanese in 1945, a portrait of Nationalist President Chiang Kai-shek was hung on the gate. Mao’s portrait, along with those of several other top leaders, replaced Chiang’s on Feb. 12, 1949 when 200,000 people gathered in front of the gate to celebrate the Communist takeover. The portrait on the gate became a symbol of possession of the city and nation.

Before 1966, Mao’s portrait was placed on the gate only for about ten days around May 1 and Oct. 1 each year. The portrait was replaced repeatedly as Mao aged. The cap was discarded as out of keeping with a head of state’s demeanor. In 1950, an image of Mao looking upward was placed on the gate. As only his right ear could be seen, the portrait was criticized as implying that Mao listened to only one side of issues. In a 1952 portrait, Mao looked directly at the viewer’s eyes. From then on, subsequent Mao portraits on the gate incorporated this gaze, reinforcing the impression that no one could escape Mao’s scrutiny. The portraits eventually incorporated a famous stockier and fatherly-looking Mao with a Mona Lisa smile.

Until Mao’s death, copies of the Mao portraits were placed at every school, factory and commune, but most were taken down after he died. The portrait on Tiananmen is the most prominent relic of Mao’s cult of personality. Former senior leader Deng Xiaoping told a foreign journalist in 1980 that Mao’s portrait would remain forever on Tiananmen Gate as a symbol of the country.

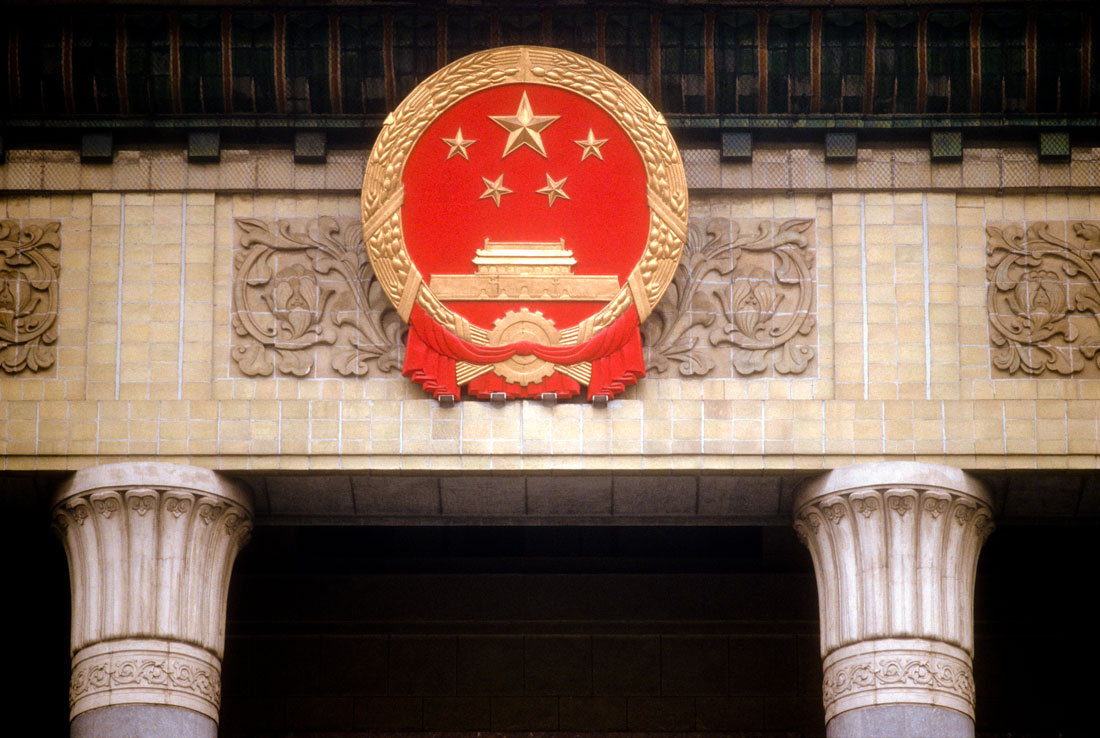

Tiananmen Gate became the symbol of the nation, enshrined on the national seal and hundreds of propaganda posters and billboards over the next 70 years. Communist propagandists made it into a symbol merging the Communist Party with the past and future of China, declaring that the party and China were synonymous and seeking to eliminate all opposition to Communist rule.

Through the 1960s, Tiananmen Gate was shown on posters and other pictures with rays of light behind it. Chinese school children widely copied the scene, and many visited the square were disappointed that there were no light rays radiating from the gate. Today, it is sometimes lit at night during celebrations to suggest that effect.

The national seal on the Great Hall of the People incorporates Tiananmen Gate.

Many have asked, probably in the grip of Beijing’s cold winters and spring dust storms, why Mao and his fellow revolutionaries chose Beijing as their capital. Sceptics have recalled the famous observation that the American revolution succeeded because it wasn’t a complete revolution, but left many British colonial institutions intact. The Communist revolution was similar in many ways, one of which was the Communists’ decision to build their capital in the city in which China’s emperors had long ruled as well as to use the “sacred space” of Tiananmen and its surroundings to lend legitimacy to the Communist regime. Mao was devoted to revolution and to dismantling China's imperial past - to a point. However, he was well-versed in Chinese history and deeply admired some of China’s most brutal tyrants including the Ming emperor Yongle and Qin Shi Huang. Mao was not adverse to using their tactics, including conscription and mass mobilization of ordinary citizens, to consolidate his rule.

The Communists revamped the Tiananmen area, influenced by Soviet advisors with grandiose Stalinesque ideas. The Communists had little respect for Beijing’s graceful imperial architecture. Their Soviet-style transformation of the Tiananmen area is considered by many today a cultural tragedy. However, they followed an ancient Chinese pattern of new dynasties razing at least parts of a former dynasty’s capital and constructing new venues for rituals and functions to solidify their authority.

Between 1952 and 1959, they stripped the Tiananmen area of old structures and created in its place the concrete square. They consolidated their power over Beijing’s residents by mobilizing them to build mammoth buildings and march and cheer at parades and rallies, including some in the square. Officials discarded suggestions by eminent architect Liang Sicheng that the city center be preserved as a historic district and an administrative city be built in the outskirts of Beijing. “I spent twenty years fighting to get in, now he wants me to leave,” Mao said of Liang’s proposal.

Beijing’s walls were demolished in the 1960s, although Liang demonstrated how road tunnels could be built under the walls to preserve them and still provide for traffic flow. “When a city gate was demolished, it was like cutting a piece of flesh from me, and when the bricks of the outer city wall were torn down, I felt as if my own skin was coming off,” Liang said. Of 8,000 buildings with historic, religious or artistic value, the Communists decided to preserve just 78. Mercifully, the country ran short of money and did not follow through with a plan to demolish the Forbidden City.

Two mammoth Soviet style buildings were added on either side of the square, with drab facades typical of those built in Soviet satellites across Asia and Eastern Europe. The Great Hall of the People on the west is where major government meetings, visits by foreign leaders and state banquets are held, and the National Museum of History is on the east side. The buildings were given Chinese golden roof tiles and monuments were carved with anonymous heroic Chinese figures marching and carrying guns.

The Great Hall of the People during a welcoming ceremony for a foreign leader.

Few foreign leaders over the past 40 years have not visited Beijing and been welcomed at a grand ceremony at the square. Here, a Queen Elizabeth reviewed Chinese troops during a welcoming ceremony on the square in the 1980s.

As the Soviet legacy has marched off into the past in much of the former Soviet bloc, Tiananmen Square survives as one of socialist realism’s major historical sites. Modern China also has discarded much of the Marxist legacy, but the government still traces its legitimacy to the Communist revolution that spawned the square. The model of a central square anchored on east and west by large buildings with avenues emanating from it was imitated on a smaller scale throughout China where historic buildings and city walls were demolished to build concrete Soviet-style buildings. The result in many towns was shabby, boring homogeneity that destroyed local charm. The buildings created horrific traffic congestion in some cities as large populations converged on a single city center to conduct official business.

The buildings are a relic of the Great Leap Forward campaign of 1959. The successful completion of the buildings in ten months was proof of the Great Leap Forward’s central premise that a mass movement could achieve victory in record time. More than 10,000 workers, artists and craftsmen built the Great Hall of the People. The Great Leap Forward generally was a national scandal, with around 30 million people believed to have died in a famine caused at least partly by the push to communize China’s agriculture within a few months.

Mao dreamed of standing on Tiananmen Gate and seeing factory smokestacks in an industrialized China. As a result, 6,000 factories were created in a city whose fragile environment lacked sufficient water or energy and had natural dust storms. The city paid for Mao’s vision with smog so thick that one can hardly see across Tiananmen Square on some days.

Like China, Tiananmen Square was seen by the Communists as public but not politically pluralistic – a space in which only the ruling party line was promoted.

Mao blocked the Imperial Way’s central axis with a large version of a traditional Chinese funeral stele, carved with his sayings and heroic reliefs depicting key historic events. The reliefs start with the burning of foreign opium that sparked the 19th century Opium Wars which initiated China’s humiliation by foreign powers. The other reliefs depict major protests, uprisings and wars that preceded the Communist rise to power. The monument was intended to create a narrative linking these events to the Communist victory. However, the monument's commemoration of martyrs who protested against past governments made it a national rallying spot for those protesting against Communism as well.

This relief on the Monument to the People's Heroes depicts a scene from China's 19th-century Opium Wars, considered the beginning of China's modern revolutionary history.

The Monument, left, and on the right, the Mao Memorial Hall and behind it Qianmen and Zhengyang gates.

Chinese traditionalists deride the square’s dull Soviet architecture as inconsistent with both the city’s imperial past and its modern high-rise present. But Chinese tourists, officials and businessmen pose by the millions each year for pictures on the square, absorbing it into their personal memories and identity.

Foreign leaders are welcomed with gun salutes and red carpets on the square. Momentous domestic and international political decisions are made in high-level meetings in the Great Hall of the People, making the square and adjacent buildings rich with history. The zero point of China’s road system is at the square.

Tiananmen Gate was extensively renovated, enlarged and modernized in 1969.

During the Cultural Revolution, huge rallies were held at the square, with Mao or other leaders viewing them from the balcony of Tiananmen Gate. About 5 a.m. on August 18, 1966, shortly after sunrise, Mao, in a green army uniform with a red star emblem on his cap, walked over the bridge beneath Tiananmen Gate, smiling and waving, shaking hands and moving among the gathered crowd. The crowd roared “Long live Chairman Mao!”

The crowds waved little red books containing Mao’s quotations and shouted slogans with tears running down their cheeks. Mao presided over eight of these rallies that year of more than a million young radicals called Red Guards. Nine million people flocked to Beijing by rail to see and hear him speak. Participants have written of waiting for days in Beijing before attending a rally at which they could barely see Mao. The rallies were imitated in provincial and village squares and reproduced on posters and clocks. The propaganda did not show that the Red Guards rampaged through China beating and detaining innocent people, ransacking houses and vandalizing historical sites. Local squares were the venue for brutal Cultural Revolution rallies. Typically, local leaders stood on a platform in a town square to conduct or watch rallies or parades in imitation of Mao. Dissidents were not allowed to attend, as the squares were considered spaces only for the Communist faithful, unless a rally’s purpose was to humiliate and persecute them. They were beaten, denounced, tortured, and paraded in a dunce cap through the squares.The abominable practice resembled the first Ming emperor’s orders that two public pavilions be built in each village - one to commend those who had done good and one to criticize those who had done wrong. As the rallies ceased in the late 1970s, many of the squares became parks.

Mao opened diplomatic relationships with the United States in 1972 at the Great Hall of the People.

Premier Zhou Enlai, who became a symbol of passive resistance to Mao’s most radical policies, died in 1976. Mao tried to quell the public outpouring of grief by banning traditional mourning. More than a million people watched on the Avenue of Eternal Peace as Zhou’s body was taken to a crematorium. Beginning on March 19, 1976, Beijing residents placed hundreds of wreathes memorializing Zhou at the Monument to the People’s Heroes. On April 4, 1976, more than two million mourners placed wreathes on the monument, sang, beat drums and set off firecrackers. That evening, police cleared the square and detained 57 mourners. The next day, mourners burned cars of the commanders in charge of removing the wreathes. Tens of thousands of troops with clubs cleared the square, injuring more than 200 people and detaining 388 people. Deng Xiaoping, who worked under Zhou, was ousted. When he later returned to power, he released imprisoned participants in the so-called Tiananmen Incident.

After Mao died on September 9, 1976, and the radical Gang of Four that supported him were arrested in a coup, thousands of people celebrated in the streets and a troop review was held in Tiananmen Square on October 24, 1976, to celebrate the gang’s demise. Millions went to the square.

In 1977, the square was expanded to its current size to hold up to 600,000 people, and a memorial hall was built there. Originally created for Mao and other revolutionary figures, the hall to the south of the Monument to the People’s Heroes overwhelmingly honors Mao. The first floor is devoted to displaying his embalmed body in a crystal coffin. The second floor has memorial halls for other leaders but most visitors only see the first floor. The hall is among the most popular and bizarre Beijing tourist sites. The placing of Mao’s remains in the mausoleum created a space to honor Mao but move on, in the tradition of placing emperors in elaborate tombs while dismantling many of their policies.

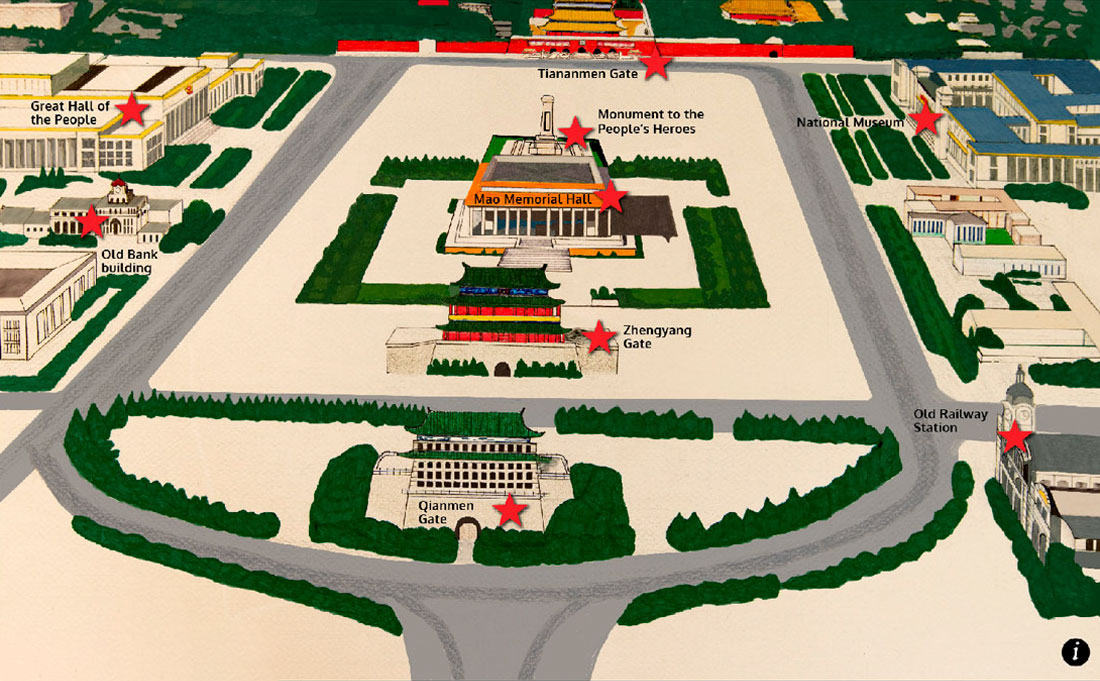

The square is a hodge podge of architectural styles and history. Counter clockwise from the upper center, Tiananmen Gate, the National Museum of History, the Old Railway Station, Zhengyang and Qianmen gates, the old bank building, the Great Hall of the People, In the center are the Monument to the People's Heroes and Mao Memorial Hall.

Some of the many key events at the square since then have included:

- On December 17, 1978, 28 petitioners at the square protested economic conditions in rural southwest China, claiming to speak for 50,000 young people who had been sent to labor in rural Yunnan province. In January 1979, several thousand of these youths demonstrated in the square with banners reading “We don’t want hunger” and “We want human rights and democracy.” Later that month, about 30,000 went to Beijing to petition for help. The state allowed most of them to return to the city. Out of this movement grew the Democracy Wall, which was characterized by posters put up on a wall at Xidan, a business district west of Zhongnanhai. Posters also were put up on the Avenue of Eternal Peace, the square and Wangfujing Street east of the square. The government tolerated them until they challenged it, after which they arrested some activists and removed the posters.

- In 1986, university students in Beijing joined a pro-democracy protest that had spread in other cities. Thousands of students converged on Tiananmen Square on December 23, 1986, pushing en masse against lines of police trying to clear the square. The protests died down in January 1987, but Communist Party Secretary Hu Yaobang was ousted after he refused to dismiss three intellectuals accused of fomenting the unrest. Hu was a committed Communist but known for his dislike of Mao’s radical policies, for rehabilitating hundreds of thousands of intellectuals who Mao had persecuted, for protecting leading intellectuals and for his relatively liberal views on political reform.

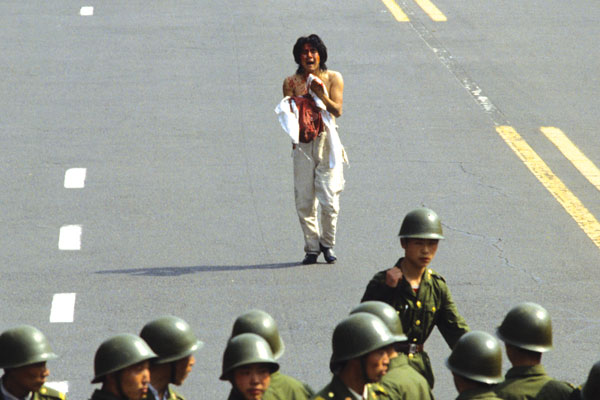

- When Hu died on April 15, 1989, thousands of university students staged mourning marches to Tiananmen Square. They placed wreathes at the Monument to the People’s Heroes, chanted slogans, delivered memorial speeches and sang songs such as the Internationale. The movement quickly morphed into a pro-democracy movement. Over the next month and a half, the protests swelled to more than a million at their peak. Protesters occupied the square, staged a hunger strike, and disrupted the visit of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev to China to reinstate relations with China after a 30-year hiatus. When the government declared martial law, residents poured onto the streets to block troops trying to enter the city to clear the square. On the night of June 3, 1989, the Chinese army blasted its way to the square with tanks, armored personal carriers and AK-47s. The army shot hundreds of people, mostly along the approach to Tiananmen Square on the Avenue of Eternal Peace, and forced the students to exit the square. A tank toppled a Goddess of Democracy statue erected by the students, and troops roped off the square, burned the students’ encampment, and stationed soldiers with AK-47s around the square for months. Communist Party Secretary Zhao Ziyang, who had refused to go along with the crackdown, was ousted and spent the rest of his life under house arrest. This marked the beginning of thirty years of leadership that pushed economic reforms aggressively and allowed the Chinese people greatly increased personal freedoms but kept a tight monopoly on political power.

Tiananmen Square during the 1989 protests.

- The government staged a 40th anniversary National Day celebration and parade in the square on Oct. 1, 1989. It was a parody of the protests, with marches by officially designated groups of students, fireworks that reminded the shell-shocked population of the sound of gunfire on June 3-4, and a statue of a worker, farmer, soldier and intellectual placed where the Goddess of Democracy had stood. Most foreign nations, who had suspended relations with China after the bloody crackdown, refused to send representatives to the celebration. Since 1989, the government has clamped down immediately on dissent in the square before it can develop, preventing further attempts to create a broader based unofficial history for the square.

- In March 1999, about 10,000 Falungong practitioners surrounded the nearby Communist Party headquarters, Zhongnanhai, just west of Tiananmen Gate in a peaceful protest against what they deemed as unfair persecution. They remained for 12 hours before peacefully dispersing. Police arrested tens of thousands of them and banned the movement. Thousands of Falungong adherents were sent to prison.

- The Museum of History, once two separate museums for pre-and post-communist history, has been merged into one national museum and renovated into a state-of-the-art facility that tows the Communist Party line in its depiction of China’s history. Landscaping changes come and go. Annual National Day celebrations and a variety of other commemorations are held on the square.

- In 2013, just before National Day, Police clamped down on petitioners throwing thousands of flyers with complaints in front of Tiananmen Gate in a reenactment of the ancient custom of petitioning before the gate.

Much of what has changed about the square in the 21st century is the city around it, as the government has razed neighborhoods and replaced them with Hong Kong-style high rises.

A street cleaner sweeps steps near Tiananmen Gate in a legacy photo from the 1990s.

Check out these related items

Thirty Years Since Tiananmen

Thirty years ago, students staged pro-democracy protests on Tiananmen Square that shook China's Communist government.

China’s Walled Cities

Only scattered remnants survive of the many walled cities that once defined the Chinese empire.

Islam in China

Muslims in China are a diverse religious and cultural group with a tumultuous history who take various sides in political disputes.

Treasure Room and Two Palaces

In the French palace at Fontainebleau is a treasure room of dazzling artifacts taken by the French army from a palace in Beijing.

The Summer Palace

The Summer Palace, the most famous and heartbreaking of China's glorious imperial gardens, highlights dilemmas in the nation’s past.

Ancient Silk Road Meets High Tech

The International Dunhuang Project digitizes old documents, caves and artifacts to enable global study of Central Asian history.