Dolls with Souls

Photos by Forrest Anderson

While living in New York City as a young woman, I became friends with a young Japanese woman who also was living there temporarily. She wanted to learn how to speak English better and I wanted to learn how to make Japanese dolls. We decided to combine our interests – she and I would get together regularly to converse in English while she taught me how to make Japanese dolls. Her mother, a Japanese doll artist, sent us the raw materials and we set to work, chattering away in English. We made two beautiful dolls and I developed a lifelong love of Japanese dolls and the culture from which they came.

That made the Ando Japanese Doll Shop a must-see while visiting Kyoto, Japan. In this small artisan shop on a narrow lane, some of Japan's finest doll makers craft exquisite dolls in layered kimonos with long elegant sleeves, silken black hair and tiny handmade props.

The Kyo-Hina dolls that Ando shop creates are dressed in faithfully reproduced historical period costumes that invoke the rich Japanese traditions of the tea ceremony, emperors, samurai and traditional festivals. The shop is owned by a family that is now in its third generation of dollmaking and has been awarded some of Japan’s highest artisan honors.

The dolls’ various parts are made by masters on the shop’s small staff and who have been taught their skills by previous masters. They hold national qualifications as artisan doll makers.

- A head-making master creates a cement head in a wooden model, and then combines calcium carbonate powder with glue and repeatedly applies it to the model to achieve a glossy finish that looks like skin. The eyes then are carved with a knife and glass eyes are placed in the cavity. The lips are painted on in red and the eyebrows are lined. Then hair is drawn along the hairline in thin black. The head is then polished to a glossy finish.

Painted heads at the Ando workshop, in the process of getting hair put on.

- A hair-making master applies the hair of raw silk thread to the head with a hot iron and comb and arranges it into a traditional hairstyle.

- A hands-and-feet master carves the hands and feet from Paulownia wood and places wires on them for fingers. Glue mixed with calcium carbonate powder is applied to the fingers repeatedly to create their skin.

- A prop-making master creates props for the dolls – tiny folding fans, swords and other items.

- A dressing master decides how the dolls will be dressed and how their hands and feet will be attached. Kyoto is famous for Nishijin silk brocade, some of which is specially woven to scale for dolls’ costumes. The color scheme of the silk fabrics blended in the many layers is considered one of the most important processes in doll making.

In the final stage, the dolls go through an eye-opening ceremony, which tradition says brings them to life. The dolls are given a gentle expression like Buddhas, which make them popular gifts for children as they are similar to having Buddha watch over them. Master craftsman Ando Tahahiko runs the shop, which has been passed down to him by his father, master craftsman Ando Keiho. The father still works at the shop.

Finished dolls at the shop.

The Ando shop makes the dolls for a variety of purposes. It has created specialty dolls for the king of Thailand’s 80th birthday in 2007 and presentations to the premier of China and the Russian president’s wife. The shop masters who supervised the doll for the King of Thailand attended the presentation ceremony in Thailand.

Dolls also are created for Japanese festivals, especially the March 3 Hina Matsuri Festival and May 5 Children’s Day. Dolls are made for special occasions such as people turning 60 years old, the age at which the Japanese believe people are reborn. These dolls, called Kanreki dolls, are clad in red layered kimonos. After the age of 60, people can continue receiving Kanreki dolls in different colors until they reach 99 years old. The shop started making these after Ando Todahiko made one for his wife, and people asked if he could continue doing so. Each one takes about two years to make. The shop also holds workshops for people who want to make Ichimatsu dolls, which are simpler, and then have tea with their master instructor.

Japanese doll making is ancient and rich with historical and cultural meaning. Human figures were created from about 14,000 BC to about 300 BC in Japan to represent gods and to use in rituals. From 300 to 600, terracotta funerary figures were made as grave offerings in the shape of people, animals and objects.

By the Heian period (794-1185), several kinds of dolls were being used for toys, in rituals and for protection against evil spirits. In ancient China, the Chinese held a purification ceremony on March 3 in which dolls were made of straw or paper. There was a belief that dolls could trap evil spirits and the person who touched one of the doll would be protected from them. The doll would be taken to a river or waterway and placed in the water or in a small boat, where it was carried away on the water as a metaphor for washing away one’s sins. The Japanese adopted this custom from the Chinese. At least as early as 3 B.C. it was being done using grass dolls at Ise Shrine, the ancient Japanese Shinto shrine. The ceremony was adapted at the imperial palace in Kyoto, initially using paper. The early 11th century Japanese novel The Tale of Genji referred to several types of dolls – ones that girls played with, protective dolls made by women for their children or grandchildren and dolls used in religious ceremonies that took on the sins of a person who touched them.

These figures evolved into decorating with dolls on March 3, the Hinamatsuri Festival, and eventually into elaborately dressed Hina dolls such as those made today by the Ando shop. Doll production expanded in the Edo period (1603 to 1867) when wealthy people such as nobles, samurai and merchants sought beautiful dolls for gifts and to display at the festival, which grew more and more elaborate. Dolls became larger and more detailed and the government regulated the profession of doll making, including height and materials used for doll making. Artisans who created human figures such as religious statues, festival cart figures and puppets developed methods for working with wood and white glue substance used to create the polished skin of the figures. these techniques were scaled down for doll construction. Weavers made specially woven cloth for small dolls and woodworkers and lacquer artisans made the dolls’ bases and furniture. Dolls spread from the wealthy classes to ordinary people.

The Hinamatsuri Festival was a time for parents to pray for girls’ healthy growth and happiness. Grandparents and parents gave the dolls to children as part of these prayers. In about 1751, the custom of including dolls dressed in royal and noble clothing became popular as a way to preserve and pass on court culture. It became a custom for girls to take their Hina dolls with them when they got married. Today, girls and their mothers decorate with the traditional dolls arranged on a hierarchical stand covered with red cloth and visit friends to see their doll collections.

The dolls, dressed in elaborate layers of textiles, represent the imperial court. A full set of dolls has at least 15 dolls that represent specific characters in the court, but a set can be just a male-female pair called the Emperor and Empress. The set includes armed guardians – a young man on the left who is responsible for warfare and an old man on the right who is responsible for the study of science. Below them on the stand are three servants who care for the Emperor’s garden, their faces showing the emotions of joy, anger and sorrow. A Minister on the Left is a wise, older statesman with a bow, arrow and sword. A Minister on the Right is a younger stateman. The stands also include miniature black and red lacquer stands, serving bowls and containers decorated with gold, as well as small fruit trees from the Emperor’s garden.

There is a tradition that the decoration must be put away right after the festival is over or the family’s daughter will marry late.

Hinamatsuri was traditionally a home festival, but in the past twenty years is often celebrated with civic displays that include hundreds of dolls contributed by citizens and living hina displays with children or adults dressed like dolls and standing or sitting in the traditional hierarchical configuration.

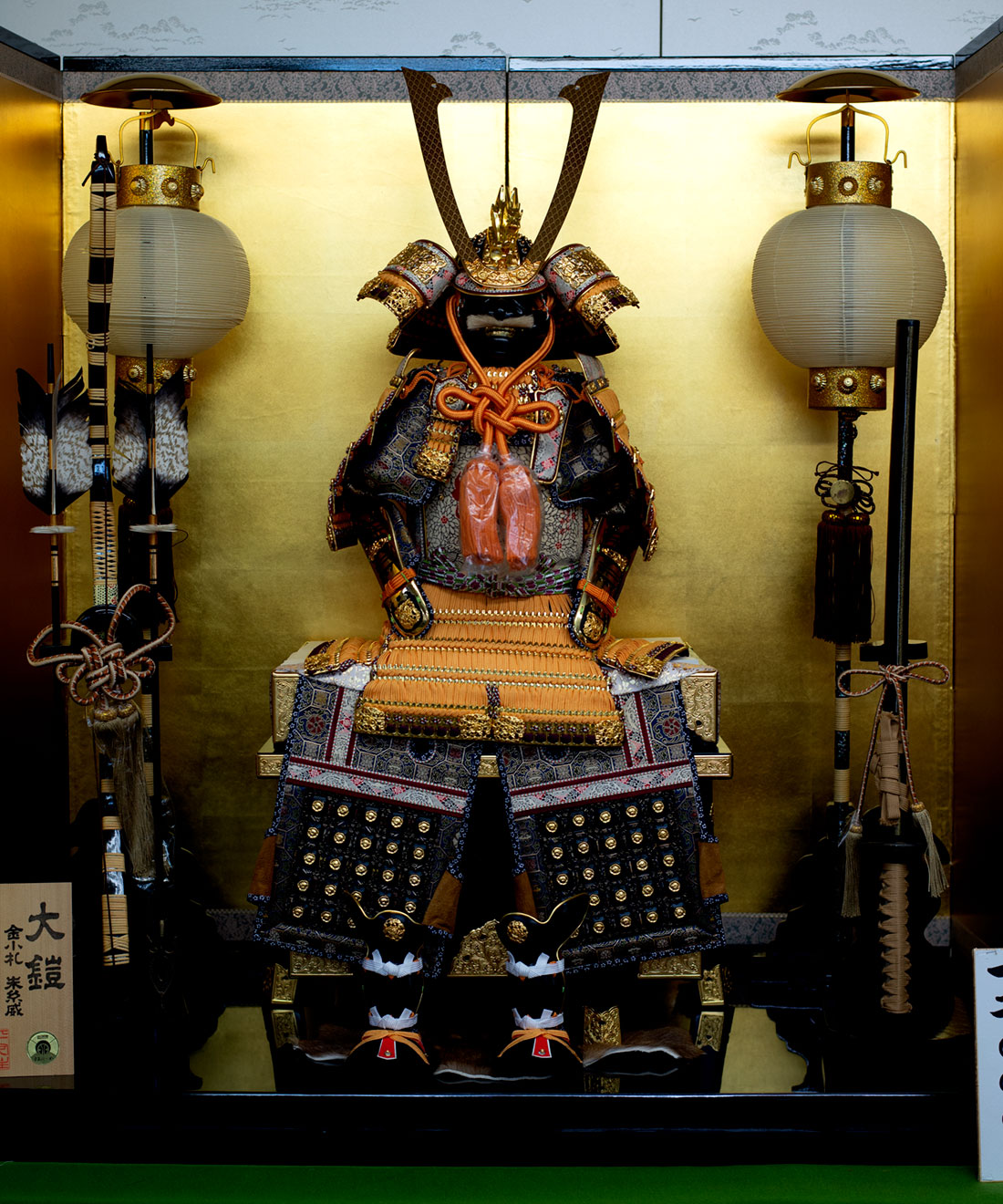

The other major doll festival, Tango No Sekku Festival or Children’s Day, marks the change of seasons from spring to summer. It traditionally included rituals for protection against diseases, disasters and evil spirits. Known before World War II as Boys’ Day, the festival celebrated military prowess until after the war when it was changed to Children’s Day. The day was traditionally associated with displays of helmets, sometimes topped by antlers, and a samurai figure is at the top level of the stand on which dolls sit for the festival. Family members send wishes for the health and success of sons and the well-being of the family on this day.

During the Edo period (17th-19th century) at the entrance of a samurai home, weapons, helmets and flags were arranged and people decorated their courtyards with fish banners and windsocks, as a school of gold fish was a traditional symbol of courage. It would appear to drift in the sky as though it were moving in water. In decorating their homes, people were praying for protection for boys and that their boy would become a good man. Kintaro warrior dolls are given to children on this day to inspire them to be brave and strong like a traditional folk hero. Also displayed are musha or warrior dolls made of materials similar to hina dolls but sitting on camp stools, standing with props such as armor, helmets and weapons or riding horses. They often represent historical or fairy-tale warriors.

A samurai doll display at the Ando shop.

Traditional dolls are given as gifts, purchased as souvenirs, and purchased by pilgrims at temples or for household shrines. They are crafted to represent imperial court figures, samurai, historical and fairy-tale heroes, gods, demons, children and babies and ordinary people.

- Hōko dolls were given to young women and pregnant women to protect them and their newborn children.

- Gosho dolls are cute babies that are often given as gifts.

- Okiagari-koboshi dolls are rolypoly papier-mache figures that are good-luck charms and symbols of perseverance and resilience. Temple sculptors may have originally made these dolls.

- Kimekomi dolls are made of wood, with grooves so that edges of cloth can be tucked into them for the clothes. This is the kind my friend and I made. They now can be made with a purchased craft kit and making them has become a popular hobby in Japan.

- Theatrical dolls include karakuri ningyo puppets, large figures on festival floats and smaller ones in scenes depicting entertainment with props such as musical instruments. They often represent legendary heroes. Bunraku puppets are another theatrical form of doll.

A musican doll at Japan's National Museum, which has a large collection of exquisite Japanese dolls.

- Kokeshi dolls are wooden dolls with no arms or legs originally made by farmers for toys for their children, but now made as souvenirs.

- Iki-ningyō dolls are life-sized dolls made by artists.

- Ichimatsu dolls represent little girls or boys.

- Daruma are round dolls with red bodies and white faces without pupils that represent Bodhidharma, who founded Zen Buddhism about 1500 years ago in India. The dolls are charms to bring good fortune, prosperity and fortitude to accomplish goals. People buy them without eyes, then fill one when making a wish, often on New Year’s Day. When the wish is fulfilled, they color in the other eye.

Other Japanese dolls are made of fired clay, washi paper or cardboard.

Japanese dolls became popular internationally when many U.S. servicemen and foreign tourists brought them home from Japan after World War II. Especially popular were ones representing geisha and maiko (apprentice geisha) in Kyoto, Kabuki performers, and dolls representing different trades and stages of life.

Japanese dolls for sale in Higashiyama District in Kyoto, a popular tourist destination.

In Japan, dolls are considered not just objects of decoration, but living creatures. When a doll's owner must throw it away, he or she takes it to a temple where dolls are piled together. The owners say farewell to their doll and express their deep gratitude to it before the doll is burned to ashes. Dolls that are offered sometimes have a function of substituting for or representing the person offering them, taking on evil spirits or sins when the person touches them. Dolls such as daruma also can be burned at the end of a year to signify the destruction of a year’s sins and follies. Burning the dolls is believed to release a doll’s soul or spiritual power when it is at the end of its life.

Talismanic dolls traditionally made for children before or at birth apparently serve as twins that confuse or distract evil spirits that bring childhood disease. These dolls usually were destroyed when the child came of age.

Some dolls, however, are passed down in families and become part of descendants’ collections.

Red or red-haired dolls were believed to ward off illness, and were placed at the bedside of a sick child. Other dolls were tied to a door lintel as a rain charm.

Some folk dolls stem from local festivals or have religious meaning. Today, many are souvenirs. Kokeshi dolls were the most famous. Woodworkers who were near hot springs made extra money by making them from scrap wood and selling them. Monks originally made dolls to sell at shrines using pottery, plaster, papier-mache or wood. Such dolls can either have a talismanic meaning or just be a nice reminder of a pilgrimage to a shrine.

Dolls also can be linked to seasons and be seasonally exhibited in the tokonoma or corner niche of a traditional Japanese house. Pairs of dolls representing an aged couple are given as wedding and anniversary gifts.

Some dolls are memorials for a dead or lost child. At some shrines, parents can offer a doll bride or husband to an unmarried dead child to provide the child’s spirit with a companion.

Japanese dolls have long reflected politics. The earliest recorded doll display on the third day of the third month was at the court of the empress Tokugawa Masako in the 1600s. By the 18th century, hina dolls were seen as representing the imperial palace. In the Edo period, laws were enacted determining who could own dolls and what kinds were appropriate for ownership outside the imperial family. Some dollmakers were prosecuted for making dolls that were larger or more exquisite than the law permitted. Smaller dolls were developed to convey luxury while complying with the laws.

In the Meiji period, when the Shogunate was dissolved and the Emperor became the official national leader, the Hinamatsuri festival honored him, and the position of the male and female dolls on stands was reversed to reflect the position of the imperial throne in the Tokyo audience hall. Smaller, less expensive hina dolls were created so that all classes could participate in the festival.

A curriculum of folk tales to teach Japanese virtues and culture to schoolchildren was created in doll tableaux. Doll artists also depicted contemporary figures, including the emperor, in modern clothes or military uniforms.

When Commander Mathew Perry returned home from Japan in 1854 after forcing Japan to open commercial and diplomatic relationships with foreign nations, he brought with him high-quality Japanese dolls that are now in the Smithsonian Museum.

In 1927-29, American children collected American dolls and sent them to Japanese children to express their hopes for peace between the two nations. The Japanese in return sent back 58 large Ichimatsu dolls that toured the United States.

After Japan was defeated in World War II, the flavor of the May 5 festival which had been dedicated to the display of armor and masculine heroes in doll form was re-dedicated to children in general.

When Japanese business boomed in the 1980s, dolls were sometimes made to order for companies to give as gifts to employees or at official events. Yamaha in the 1980s gave dolls annually to its distributors to display in their showrooms.

Hina dolls were ceremonial dolls, not toys, but Japanese girls also played with dolls. Traditional doll making is a popular leisure pastime among Japanese women, indicating that the line between dolls as toys and ceremonial dolls is somewhat blurry.

I have another special memory of my friend who taught me to make Japanese dolls. My family and I later lived in China. When we had to evacuate to Japan during a period of political unrest in China, my friend had returned to Tokyo. We called her from our Tokyo hotel to say hello. The next day, she and some of her friends met us at the airport in Tokyo when we went to board a plane for the United States. They brought with them bags of toys for our children to play with during the flight.

Check out these related items

A Minimalist Tries Marie Kondo

A confirmed minimalist finds that Marie Kondo's tidying method helps her to refine an understanding of what brings joy.

A Palace to Remember

Visible traces of the Heijō Palace, Japan's palace from which the emperor ruled in splendor, were gone, until the site was restored.

Battle of the Samurai

Osaka Castle marks the site of an epic samurai battle and one of the most important turning points in Japanese history.

Elements of a Japanese Garden

Imagine you're sitting in Los Angeles traffic on a hot day. Take a break and head for a cool green oasis - Suihoen Japanese Garden

Giant Buddha, Giant Hall

An emperor built a giant Buddha to unify his struggling country, as the center of a network of Buddhist temples throughout Japan.

Japanese Design Past and Present

Architect Kengo Kuma's village at the Portland Japanese Garden blends modern architecture with traditional Japanese design.