Making Your Own Family Museum

Photos by Forrest Anderson; painting in the public domain.

“The family is the largest special interest group on the planet. … There is simply nothing larger, more encompassing, or more powerful in human behavior than the family and its consequences, whether benevolent or detrimental.”

— Victor L. Brown

You belong to the world’s only universal institution, the family. Since you are reading this blog entry, you may be among the 60 percent of Americans who are interested in family history. You also may be among the 40 percent of adults who visit museums.

You may be an antique collector, history buff, quilter, gardener of heirloom plants, photographer, scrapbooker, artisan baker, or some combination of these. Perhaps you are a parent or grandparent who wants to pass on your family heritage to your children without boring them to tears.

If so, this blog entry and the hobby it explains are for you. Making your own family museum is a natural outgrowth of all of the above popular hobbies and interests, and it is the most fun of all because it’s about you and your loved ones.

We are accustomed to going to museums or historical sites to experience history first hand. We trek by the millions to Williamsburg to experience colonial life, the Smithsonian to see Abraham Lincoln’s hat, Gettysburg to see the battlefield where thousands of Americans died. We build memorials to honor our war dead. We take classes, go on tours and cruises and buy books to discover the past.

Yet most of our history is right where we are, at home. Stuffed under beds, on closet shelves, out in the garage, down in the basement, and up in our attics is a treasure trove of our nation’s history. Museums hold only a small percentage of historical artifacts. The rest are held by private collectors who wouldn’t dream of parting with great great grandma’s organ that survived a flash flood in 1900 or great grandpa’s carpenter tools and the cabinet he built with them during the Depression.

Your stewardship over these items is important to America’s and your family’s history. You can display and preserve them as well as a museum can, and doing so is an enjoyable and deeply satisfying hobby that can draw your family together.

A family museum can be as small as a display of photographs or a shadow box on the dining room wall and as elaborate as an entire restored historical home. It can cost you almost nothing or thousands of dollars, depending on your interest and resources. It’s the ideal scalable hobby. It can be engaged in during an hour stolen from a busy schedule or pursued for hours and days at a time.

This simple display tells a story of my family's migration and settling in the United States. In the top left frame is a copy of the foreign passport my great grandfather used to get into the United States. The top right is he and his family after he had become a prosperous Colorado rancher. The other two pictures are his descendants in my direct family line.

The photo below shows the family museum I created in an awkward corner of a house we used to live in, which was the only space available. I occasionally swapped out the displays for others using other heirlooms that I had stored away.

Having a family museum is fun, but it also is serious business. The magnitude of the challenges to the permanence of the American family are without precedent and have brought calamity upon parents and their children amid an onslaught of emotional disorders and societal upheaval. Successful, multi-generational families and marriages are showcased less and less in the media. Working adults are subjected to constant pressure to put careers before family, pushing the family out of a central role. The mobility of many families robs people of the personal and family identity that comes in communities in which their families are known.

A family museum can help counteract these influences by being a visual reminder of the multi-generational nature of your family and your identity as a member of it. A family museum can celebrate successful matrimony, the priceless heritage that are your children, and values that helped your ancestors survive past crises and challenges. It can showcase loving, responsible, nurturing mothers and fathers who don’t get recognized elsewhere, thus inspiring respect for them. It can remind you why you love each other.

A family museum can allow your family to discover parts of its history that have been lost in obscurity, show what life was like for your family in vanished times. Your museum can teach you and your children who you are.

I was raised in what amounted to a living history museum. I spent most of my young childhood weekends, holidays and summer vacations on a ranch in the high Rockies of Colorado that had been homesteaded by my great great grandfather, Elijah Adams McGregor.

I slept, played and ate in the hand-hewn cabin Elijah had built in the 1890s. The log woodshop where Elijah had worked as a carpenter, creating some of the cabin’s furniture, still held Elijah’s tools. I waded in the irrigation canals he had dug, and ice skated on them in the winter.

On the hill above the ranch, Elijah’s grave watched over the ranch while his stern portrait on the wall kept an eye on my behavior in the cabin. During ranch dinners, I listened to my elders tell colorful stories about him. I absorbed his value system of humor, hard work, neighborliness and strict honesty long before I could have articulated the meaning of those words. By the time I was a young adult, my life was intertwined so tightly with that of my ancestors that I could not have separated my identity from theirs. Most of my ancestors were dead by the time I was 21, but the legacy I absorbed as a child has always given me a sense of who I am and what is expected of me.

Many homes lack this type of legacy. They are comfortable and beautiful, but you would think the inhabitants were Adam and Eve from the lack of evidence of their family heritage. Hiding our legacy in filing cabinets and cedar chests rather than living gracefully with it deprives our visually oriented children of the opportunity to learn naturally about their family’s history without us boring them with lectures.

Instead, you can turn “all that old junk” you have inherited into a family museum by combining heirlooms, photographs, documents, and family legends to teach your family naturally about its past.

Making a family museum also can help you set in order and preserve your heritage and fulfill your stewardship to pass it on to your children.

A family museum can enable your family to experience its history through sight, hearing and touch. It gives context to your heritage so that it becomes real to your family.

A museum is an effective way of teaching your values to your children, who will become in large measure an extension and reflection of family teaching. A great deal of knowledge is passed down only in families. A family museum remembers the things you and your ancestors have seen and teaches them to your children. It helps your children see beyond the moment to have a long-term perspective. It helps weave into their fiber the moral strength they need to navigate the seas of adversity they will encounter. It helps them to do more than go along with what they find in the world.

A family museum should highlight your most treasured relationships, showing husbands and wives living joyfully together, family members loving each other, parents and the elderly being honored and children being loved and encouraged. It should gather the generations of your family together and be a unified symbol of both spouses’ heritage. It should show men and women working as equals.

In a world in which schools and organizations emphasize external recognition for success, a family museum can be a comforting sanctuary in which children learn obedience, love, industry, gratitude and tested internal standards of conduct.

Here's how to make a family museum:

You don’t have to turn your house into a museum to have a family museum. Museums only display a fraction of their collection at any given time. Most activities of a museum are behind the scenes. The most important and basic is care and preservation of the museum’s collection. Properly caring for the artifacts that make up your family’s tangible history so that they can be passed on to the next generation should be the priority. Here’s how:

1. Make an inventory of your family heirlooms.

This is a record of heirlooms you own that will be passed down to your heirs. A locket goes from being a trinket in a jewelry box to being a valued family heirloom when it is listed on an inventory list as “Grandmother Ida Johnson’s locket, gift from her husband James on their wedding day.” When the locket is linked with a photograph of the couple that shows Grandmother Ida wearing the item, the locket takes on added meaning. If brides in later generations of wedding photos are wearing the same locket, the item goes from being a meaningless piece of jewelry to a family tradition. Unfortunately, if that tradition is only an oral one, it is easy for your heirs to miss the locket’s meaning and allow it to join items in an estate sale. Severed from its lost history, the locket becomes just another orphaned relic in an antique store. Only by keeping a written record of your heirlooms can you ensure that their history will be preserved.

An inventory also is useful for insurance purposes in case you have a flood, fire, or other disaster, and as part of your will. Some of the most valuable documents at historic house museums are will inventories which allow historians to reconstruct the furnishings in those houses. Your inventory could include instructions as to who is to inherit each heirloom.

It is far more important that you have an inventory than that you do it in any particular way. It’s useful, however, to photograph each heirloom and keep a record with the photographs telling the historical significance of each item. You should print a hard copy of it and put it with your will and insurance records. Give copies of the inventory to people who will inherit items.

If you don’t have time to make a detailed inventory, start by writing a general label of what is in each box of family heirlooms, such as “Items that belonged to Emma McGregor, 1890-1925. She was the daughter of Elijah McGregor and lived in Gunnison, Colorado. This box holds her wedding china and other personal items.”

Make two copies of this label, one which you attach to the outside of the box, and one which you keep in a file with your vital documents. The point is that if you died tomorrow, your heirs will know the significance of this box of old stuff.

Inventories can include a brief description of an item, a date or an approximate date if possible, the name of the person or people who owned it (their full name, not “belonged to Grandma”), perhaps the place and any stories associated with it. In some cases, it is useful to include the chain of people who owned it and passed it on to you. This is called an item’s provenance and it can be an important part of its historical value.

Here is an example:

“Ring box for the engagement and wedding rings of May Nichols Rouviere of Powderhorn, Colorado, who married Alfred Leon Rouviere of Iola, Colorado on June 29, 1913. Box in possession of her granddaughter, Donna Rouviere Anderson.”

2. Organizing family artifacts.

You need to bring a sense of order to your collection in order to display, properly store, and preserve it for future generations. The standard cedar chest approach, in which documents, photographs, linens, leather-bound albums, china, silver, and antique jewelry are packed in together is a nightmare from the perspective of preserving your family heirlooms. Most items stored this way are not labeled, so that the items’ history is lost when the owner passes away.

Worse is the common practice of storing heirlooms in cardboard boxes in unheated or uncooled attics, basements, or garages. This exposes your treasures to damaging temperature and humidity fluctuations, insect infestation, and, in the case of basements and attics, possible water damage.

Where do you begin with a stack of unorganized boxes that spans generations? The best way is by keeping in mind the most important organizing principle – the story. It is the story that makes most family heirlooms valuable.

Get out your family heirlooms, a box at a time, and spread them out on your table or bed. Ask yourself why you are keeping each item or group of items, and jot down your answers. “My grandmother’s sewing basket reminds me of the many beautiful things that she made over the years, and that she taught me how to sew.” “My father’s military medals are evidence of his dedication to his country. This is a value that I share. I am proud of him.”

Ask yourself what your heirlooms are telling you. What is their story? Each item has a story about your family history. It is a genealogical document, which makes it worth preserving and passing on.

The story is the main unifying principle for the organization and display of your heirlooms. Your main goal is to preserve and pass on this story.

Go through each box and sort its contents. If it is basically in order, don’t change that order because it could mess up connections between items. If a box contains a wedding dress, veil, silk flower bouquet, wedding or engagement photographs, a wedding invitation, guest list, china, silverware, and other gifts, don’t separate these items because they are obviously connected to one event. Keep them together and set them aside.

Here are some types of stories that heirlooms may tell:

Major events. World War II is a major event in almost all family histories because entire generations of cousins served in the war. Medals, ration coupon books, posters, telegrams, newspaper clippings, buttons from uniforms, and photographs all are evidence of the war.

Migrations are other life events. Humpbacked pioneer trunks are common treasures because they were used in migrations. I put together a small display of my Mediterranean heritage that includes a copy of an immigrant ancestor’s passport and photos of him and the next two generations of that family line. My grandfather on this line collected and played harmonicas, which I placed in a shadow box. I discovered that harmonicas were traditional instruments in the area that that branch of the family came from. They are a link between my American family and their southern European ancestors.

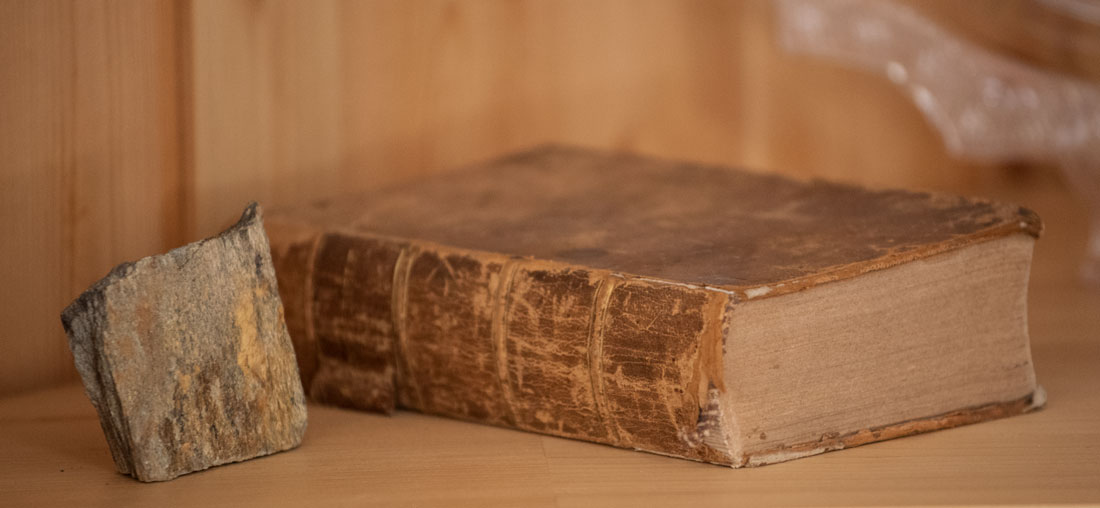

It doesn't take much to make a migratory connection in a display. This French Bible that was handed down on my family is with a rock from the village in Europe that my ancestors came from. For over a millennia, houses in that area have been built with this type of stone.

Transitions, beginnings and ends. We keep the tassel from our high school graduation cap because it represents a significant transition in our lives. People keep a lock of hair from their baby’s first haircut or momentos from funerals for similar reasons.

Evidence of important national or international events and our participation in them. My former neighbor was a White House helicopter pilot for several presidents. He displayed a framed collection of Christmas cards he had received from the first families whom he served. My husband and I have a collection of similar momentos from our international journalism career.

Some items are important for the opposite reason. They invoke memories of ordinary everyday life, or our day-to-day association with someone. Among my family heirlooms are my father’s saddle and bridle, which invoke a century of ranching in Colorado. Carpentry tools, recipe books, cooking utensils and sewing boxes all are momentos of daily life.

When you have identified why the items you own are important to you, return to your inventory and add what you have learned to it. Then go to your and your relatives’ photo and document collections, including letters, journals, scrapbooks and photographs, and look for information that connects to your heirlooms. For example, look for a picture and diploma to go with the above mentioned graduation tassel. You’re piecing together a story.

Suppose you own a pioneer trunk. Look for its possible travel route in family journals, histories, census records showing where your family lived, employment, or land records. Knowing this information vastly increases the value of heirlooms to you and your family and brings out your family’s story. Archealogists ideally look for both a written record and artifacts to understand past civilizations. Absent one or the other, they can’t be sure they are drawing the right conclusions about what they find.

A small shell on a leather string is worthless until you find out that archaeologists discovered it in the ruined foundation of a slave cabin. Suddenly, it becomes a priceless link between American slavery and African customs. It is its role in an important story that gives it value.

Out of this process, begin to draw conclusions. What is the basic chronological narrative as shown in the family heirlooms? What are the high points? You can’t display your family’s entire history. Pick out the important high points. This is what museums do.

3. Displaying Parts of Your Collection

Use what you have discovered to write a brief history of your family. This clarifies your vision for your family museum. Use this history to help you create family museum displays.

Write a statement of the purpose of your museum. What are you interested in preserving and displaying? What don’t you want to collect, display, and preserve? It is not possible to properly display and preserve everything about your family’s history. If you did, your home and life would be a junk shop. Define the purpose of your museum and the type of heirlooms you are interested in displaying. This is what museums call a collections policy. You may be interested in preserving the history of one ancestor or one family line. My concentration has been on my father’s family because the heirlooms I own are from that side of my family.

You may be interested in collecting a particular type of items. Because we have a professional background in photography, we have made a point of collecting family photographs.

Using your brief history, inventory list, and statement of what you want in your museum, identify themes around which you could create displays. Identifying three to four will simplify your project and make your displays more meaningful.

For example, from my family’s history of ranching in Western Colorado, it would be natural for ranching to be one of my themes. My inventory shows that I have a saddle, a bridle, some spurs, a branding iron, an old brand book, and ranch photographs that I could use in a display.

By looking at my inventory, I also saw that I had a number of items that came from my grandmother’s kitchen. This was a natural theme for my museum. Eventually, it grew into the interior design theme for the kitchen in the photo below. The stove is a 1933 Home Comfort one, and the chairs and Hoosier Cabinet are refurbished ones that were in her kitchen.

I decided to do a communications display because my family ran a community post office for 95 years, my grandmother was the local telephone operator, and my grandparents were local newspaper correspondents. My husband and I were foreign correspondents in Asia and have items that we collected from that experience, so I put together a display that included those items.

I also decided to do a children’s display because I had children’s toys, books, and school items spanning five generations.

Women in my family loved to sew, and do textile crafts, so I created a shadow box of their antique sewing notions that I hung in my sewing area.

You may come across smaller subthemes. For example, I framed my grandparents’ wedding picture with some of their monogrammed jewelry from the same era.

Your themes can focus on work, education, religion, the military and other aspects of life.

Think about who the audience is. Who will see your family items and what will interest them. What kind of experience do you want them to have?

If your family once ran a grocery store and that is one of your themes, you can make a small store that displays heirlooms from the store but also has for sale postcards with family pictures on them, candy or little toys for children in the family to buy, or a gumball machine. An activity center such as this speaks much louder than a display of photographs of the store.

Decide how to display items based on the space you have, the objects you want to display and the function of your rooms. I display family heirlooms that relate to the function of various rooms in those rooms - antique ceramics in the kitchen/dining room area, an old typewriter, camera and ink box in my home office and antique tools in our craft room.

If you own antique tools, carpentry may be a good theme. Children's toys from different eras can be another.

If you are like most people, you want to display your heirlooms in such a way that you convey the rich meaning behind them without making your home look like a museum. This is a delicate balance, but it’s possible to convey a great deal of information about an heirloom in a small space without making your home look like a museum gallery.

If you prefer to keep your home streamlined and modern, consider temporary exhibits of family heirlooms for special family occasions such as reunions or holidays. Thanksgiving and Christmas are a great time to bring out family heirlooms as families are focused on family traditions.

When our daughter got married, we had just moved into a home that wasn't finished and I had been injured in an accident, so we didn't have a lot of resources or time. We improvised by displaying family heirlooms, including some items that her great great grandparents had received as wedding gifts, as part of the decorations. On the tables, we used sets of family silverware and china that ranged in age from 150 years old to modern. We mixed and matched them, and the guests had fun talking about the different styles as they ate lunch.

The christening of a baby can be a fun time to bring out old christening gowns and photos of babies. Even if old gowns are too fragile for a baby to wear, they can be displayed.

Temporary exhibits also can be portable, so you can take them to reunions and other family events and set them up. They can be accompanied with food made from old family recipes. Items that are fragile or that can be damaged by long-term display, such as textiles and old photographs, are better displayed on a temporary basis.

Permanent exhibits should be of more durable items such as furniture and ceramics. You can integrate them into your rooms as part of the décor and function, or if you have the space, devote an entire room or section of your house to family history.

A family museum isn’t a quick-fix craft hobby. If you pursue it as a long-term, enjoyable activity, first making a general plan and then working on the parts of your plan one by one, you will find your family museum coming together and providing many hours of enjoyment for you and those you love most.

Check out these related items

Organizing Family Heirlooms

Now that many of us have cleaned out our closets, we need to store heirlooms, photos and documents properly. Here are some tips.

Enchanted Land, Part 1

A search for ancestral roots in southern France leads to a legendary land with a walled medieval town and tales of a magic sword.

Enchanted Land, Part 2

Old stone houses, leather books with swirly handwriting and a village church mark the second part of our journey to the Rhone-Alps.

Home is a Destination, Too

Need a five-minute stress reliever while sheltering at home? See these photos of my beautiful mountain village of Mapleton, Utah.

How Crafts Help Us Cope

Crafts are booming as people shelter at home during the pandemic. We explore why, as well as ways to learn a new craft without stressing out.

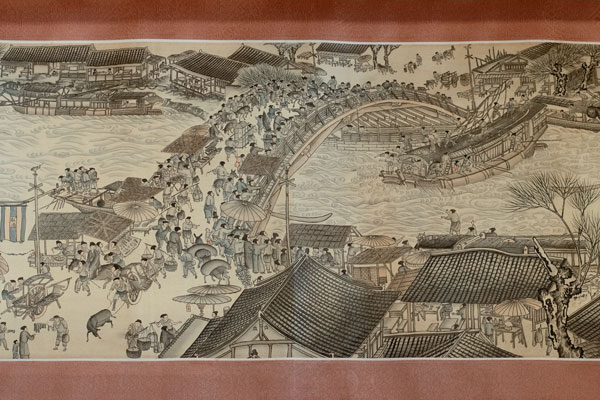

Making a Box for a Chinese Painting

We built a wooden box for a treasured hand-painted copy of China's most famous painting - Along the River During the Qingming Festival.