Organizing Family Heirlooms

Photos by Forrest Anderson

While sheltering at home, many of us have cleaned out our closets and hauled boxes of unwanted items off to thrift stores. A lot of what is left is heirlooms, photographs and papers that we value for their connections to our lives and families and want to pass on to future generations.

Some experts believe that 80-90 percent of museum-quality historical artifacts and papers in the United States are in private collections rather than in public museums or archives. These collections have immense historical value, as they are evidence of events, historical currents and people who may not be extensively documented in public records. The United States and many other countries don’t have great records of ordinary people earlier than 1900. In many cases, people who lived before that are known only through private papers. Historical experiences such as migrations West or from South to North are known primarily through information in private collections.

The items in private collections vary greatly, from photographs in a wide variety of formats to papers, old albums, scrapbooks and diaries, family Bibles and other books, clothing, china, metal and wood objects. The different materials can make it complicated to preserve them.

These historical items are made of many materials - paper, metal, textiles, leather and ceramics of all kinds. To preserve them properly, we need to understand and protect against the threats to their survival.

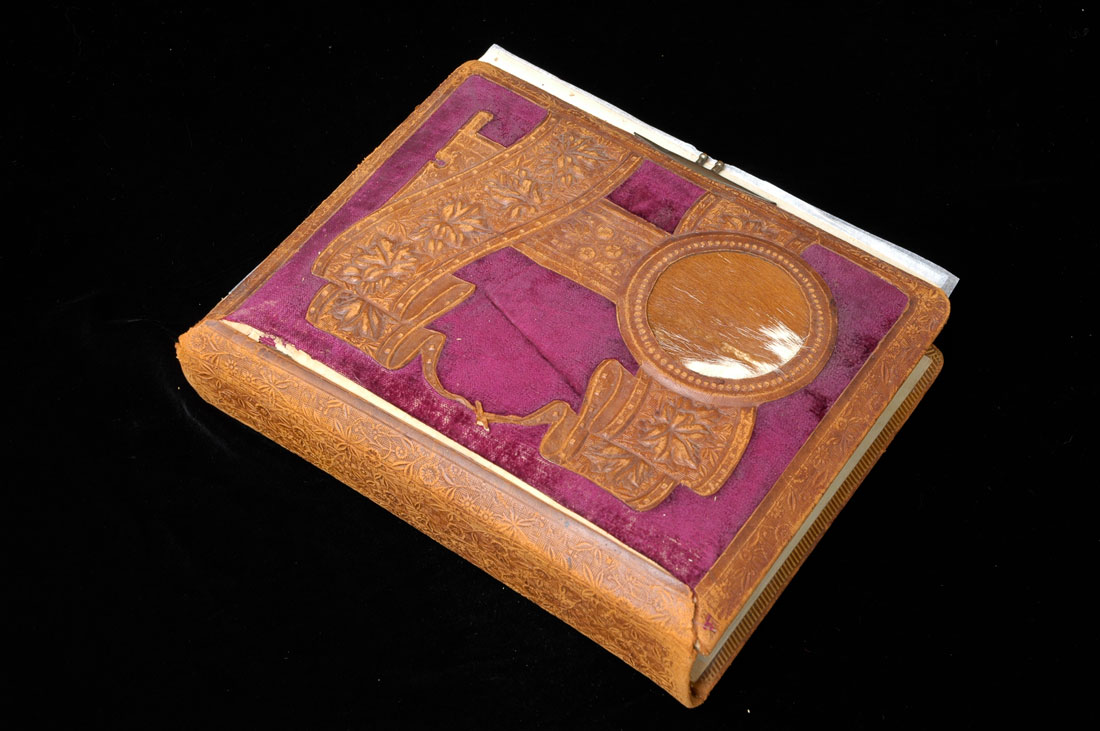

No medium is totally permanent – even stone wears away over time. However, different materials are threatened by different conditions. Porcelain is durable but fragile. Paper can last for hundreds of years or disintegrate quickly depending on its chemical content or the conditions in which it is stored. Leather, which once was used for a wide variety of objects from book covers to saddles, naturally disintegrates over time as do textiles.

Leather and textile items such as this antique saddle will irreversibly disintegrate over time regardless of efforts to preserve them. You can slow this process down somewhat by keeping them in a stable environment.

The primary threats to preserving heirlooms are:

- Heat – Both in the form of high or fluctuating temperatures and fire.

- Light – It is highly damaging to papers, photographs, textiles and other organic materials such as leather, wood and baskets.

- Water - In the form of both high humidity and flooding.

- Dust – It abrades surfaces and stains. Cleaning heirlooms of dust also can damage them.

- Pests and mold – Many artifacts such as paper and photographs, textiles and other organic materials are susceptible to damage from pests and mold if they are not carefully stored.

- Breakage – China, papers, textiles, and old wood objects are susceptible to breakage if not stored, moved and displayed carefully.

- Chemicals – Acid in particular damages organic materials. So do some cleaning agents.

- Separation from historical context - Most artifacts are primarily of historical rather than monetary value, and lose much of that value if the context in which they had meaning is lost.

Caring for family heirlooms and prolonging their lives requires keeping these eight threats in mind and setting up a storage and use system that minimizes the possible damage from these sources.

Here are some tips:

Storage

Never store heirlooms in the garage, attic, storage unit, shed or other unheated, unconditioned space. Temperatures and humidity fluctuate widely in these locations and they are prone to pests. Instead, store them in a closet, cabinet or drawers or in a storage room where you can control the temperature better, at about 68-70 degrees. Humidity is harder to control, but it should neither be very low or very high to prevent mold from growing and extreme humidity fluctuations that could cause materials to expand and contract.

Basements can also be problematic if they don’t have good temperature and humidity control. They also can be prone to flooding, so avoid storing vulnerable heirlooms in them. Try to avoid storing items near plumbing pipes or heater vents. These conditions can be difficult or impossible to avoid, so do the best you can. Store valuable items at least a foot off the floor in case you have a flood.

The most valuable historical items should be stored in a fire proof box, but it should be kept unlocked so that a burglar can look in it and see that it contains only papers. In many cases, burglars have taken off with entire fire proof boxes or safes only to break the locks on them and discard the contents in a river after extracting items of monetary value.

Display

Don’t display valued items that are prone to fading or light damage in direct sunlight. If you want to display photographs and documents, get a copy of them made to frame and display instead of the original. Then store the original away in a dark location. I used to do photo restoration, and many of my clients were very disappointed to find out that when an original photograph or document fades or is damaged, the damage is permanent. The best that can be done is to copy it and restore the copy. Depending on how they were produced, many photographs and documents will last for a long time if they are stored out of the light and away from fluctuating temperatures and heat. Textiles fade quickly and fibers break down when they are exposed to the light so if you want to display them, it is better to do so in bedrooms in which you can close the curtains during the day or on walls where they are not exposed to direct sunlight. Other organic materials such as wood and leather also break down when exposed to direct sunlight. If you want to display historic textiles such as quilts, do so away from direct sunlight, refold them to expose a different section or swap them out for another item every few months so they aren’t in the light all the time. These strategies will prolong their lives.

Avoid Acidic Materials

Acidic materials are highly damaging to organic artifacts that they come in contact with such as papers, photographs and textiles. Ordinary cardboard boxes are acidic, so don’t store heirlooms, photographs or family papers in them. Instead, use acid-free storage boxes, which used to be expensive but now are available at craft stores for reasonable prices. A cost-effective strategy is to purchase a few at a time using coupons. Always check the package to make sure that they are acid-free. Separate items by wrapping or layering them with acid-free tissue between them. Many paper items, especially books from the 19th century or early 20th century, are themselves acidic. It’s a good idea to keep them separated from other items so the acid can’t migrate from one item to another one. I store such items wrapped in acid-free tissue in boxes away from other items. Don’t wrap antique items in newspaper or keep them in the same box as newspaper clippings because the paper on which newspapers are printed is highly acidic. Newspaper clippings should be stored isolated from other papers in a separate folder and box.

Support Fragile Items

Store fragile items with supports around them. This includes old textiles. You can wad or roll up acid-free paper or tissue to make supports. Old textiles are best stored in large acid-free boxes layered with acid-free tissue between them. Minimize the number of folds, as textile fibers often break along folds, and don’t place rubber bands or other ties around them. Some items can be rolled to avoid folding them. Old china should be carefully secured with museum putty to display shelves or in supports if hung on the wall.

Don’t Separate Items From Their Historical Context

Perhaps the single most damaging thing that can be done with historical artifacts of any kind with the exception of burning or throwing them away is to separate them from their historical context. This is one of the most common mistakes that people make with family heirlooms. It happens in a number of ways, some passive and some more aggressive. Busy with our lives, we take photographs but don’t caption them. Eventually, when people die and leave their collections of uncaptioned photographs to family members, much of uncaptioned photographs’ context, history and significance is lost. There is an inevitable pile of mystery ones that no one in the family knows the identity of.

This also happens with heirlooms that have not been inventoried so that no one knows what branch of the family owned them, the family stories behind them, how old they were, who made them if they are handmade items or where they came from.

Old christening dresses are a dime a dozen - babies in many families have worn them. What gives this little dress meaning is that the baby in question died in a typhoid epidemic, along with her brother, not long after her picture was taken in the dress. The bereaved mother and then the baby's sister kept the dress and picture and passed them along with the story onto their descendants.

When a person dies, such belongings typically are divided up among family members, given away or sold at estate sales. The historic connections between items and family members is severed forever.

This isn’t a big deal with many ordinary daily use items, but it’s sad when it happens to family Bibles in which family histories are written, photographs and photo albums in particular. If they date from the 19th century, they often are the only record of births, marriages, deaths, family relationships and migrations that exists.

A more damaging way of destroying historical evidence is when people rip photographs out of albums after the owner passes away, thus severing an item from its original associations and often captions or other valuable information. I have seen this done several times, and, as a historian, I was horrified. In one instance, a family descended upon the home of an elderly woman who had died and who had been the keeper of the family history for years. She was almost blind, and had painstakingly used a magnifying glass to write captions for photos in that she placed in albums. People ripped photographs out of her carefully created albums, separating them from the wealth of information she knew about their content. Such destruction robs photographs and documents of much of their historical significance. It’s inexcusable in an era when it is easy to have albums copied and digital copies distributed to all family members. Many people insist on such actions so that they can have an original copy of a photograph, but photographs are just printed on pieces of paper. It’s the information in them and associated with them that is of value, and that can be preserved well in a copy.

The only reason that removing items from a historic album or scrapbook is justified is when the album itself was created with very acidic materials or plastics that are destroying the photographs and the caption information associated with them. In this case, the items should be carefully migrated to an acid-free album along with the captions in the order in which the photographs were placed in the original album. This should not be done with very old albums, as their chemical composition has stabilized and the albums themselves are historically valuable.

To protect items in an album, acid-free tissue can be placed between the pages. This is also a good idea when filing historic papers that may contain acid.

Store old albums with acid-free tissue between the pages to protect the photos. Don't remove items from old albums or scrapbooks.

Historic papers should be filed in acid-free files with acid-free labels on them that describe the contents. Then they should be placed in fireproof boxes or acid-free filing boxes that are labeled. To protect papers from being scattered and their context lost, it’s wise to leave instructions in your will that they are to be kept together in their boxes and albums and to provide family with digital copies of them so that they don’t initiate a free-for-all after you die and cart such items away willy nilly.

My experience has been that many people who collect old items after a death don’t actually want them or want the responsibility of preserving them. They are simply reacting to the emotion of the moment. In handling the estates of a number of family members, I always have photographed all items and given all family members digital copies. Many are quite happy with that. In numerous instances, people who have taken away boxes of papers or other items have later sent them back to me and asked me to properly care for them as they were no longer interested in keeping them.

This leads us to inheritance of family heirlooms. No one deserves to inherit anything. Such decisions are entirely at the discretion of the person who owns them, and the wisest way to preserve heirlooms is to pass them on to the person or people most likely to appreciate and preserve them properly, with instructions in your will that all items are to be available for viewing and photographing by other descendants who want to see them. With rare exceptions, family heirlooms have little monetary value. Most are ordinary items that are valuable because they are evidence of a family, community or a nation’s history. The major concern should always be preserving them for future generations to learn from. Most family collections have a few items that are crucial evidence of important family events. They also have a variety of other items that have been passed down but have only marginal historic value. Such items can be dispersed to family members while keeping items that are crucial to understanding a family history together and willing them to the person most likely to care properly for them.

Using Heirlooms

Sometimes people want to both use historical artifacts and preserve them. For example, a prized piano, jewelry and furniture are items that retain both functional and historic value. Using such items is fine. No one wants their home to be a museum for unused antiques. However, it’s important to understand that using antiques probably will shorten their lives, so you’re making a tradeoff. You may want to be more careful with a one-of-a-kind historically significant item than with ordinary use items that are old. For fragile ones, perhaps you can use or display them mainly on special occasions so that your family can enjoy them and learn about family history. Sometimes just hanging items securely away from direct sunlight can enable you to enjoy them without damaging them.

Many less fragile items can be used and enjoyed without worrying about damage to them because other than the fact that they are old, they don't have a lot of value outside of sentiment. Some can be given a new life and use. We use antique dining chairs that have been in my family for six generations. However, I restored them extensively because they were in very rough shape when we inherited them. Their main value is sentimental. We also use an old Hoosier cabinet that I adapted into a modern baking center, a large kitchen cabinet that my great great grandfather built and a 1933 cookstove that my ancestors owned and that we modernized with an electrical cooktop. As these were in poor shape and had little monetary value when I inherited them, I felt free to restore them and use them daily. I would not be as nonchalant with items that were in good condition or were more valuable. This is a judgement call that will vary with historic items.

It Takes Time

It’s time consuming to organize and label historic items. You can save some time by simply putting a label on the outside of the box outlining what is in it, who you got it from, where and the dates of items in the box. Papers can be filed with a list or label on the folder describing the contents, where you got them, how they fit into your family history and when they date from. You don’t have to write a lengthy explanation about every item, but you should record stories associated with important ones. Each label should answer the questions of what the items are, when they date from, where the items came from, who owned them and why and how the family acquired them.

Photographs are the most time consuming because each person in them needs to be identified. It saves a great deal of time if you caption them as events occur and keep photographs together that represent the same group, time, event and place. That way, you can batch label a whole bunch of them together in the computer. When captioning photos, use people’s names, not words such as “Grandma,” “Mother” or “Cousin Susan.” Within a couple of generations, these family titles will be useless in identifying people. Always include the date or approximate date, family relationships when necessary to the context of the photo, and the place. Places in captions on photos can become very useful to later generations in researching a family. While it is better to have a caption for each photo, a label on an entire batch of photographs giving general information about them is far better than no label at all if you are crunched for time.

When you get professional photographs taken for events such as a wedding or for family pictures, ask for extra prints of the ones you want to display and store the copies away out of the light or take a digital photo of them and keep it. That way, when the photos on display fade in the light, as they inevitably will, you will have copies so that you can get new prints. This is a good idea even if the photographer tells you the prints are archival, as all photographs eventually will fade in direct light.

Display photographs in frames with glass over them and mattes that separate their surface from the glass, as they can stick to a glass surface when the weather is humid. This will damage them.

Dust

Wash your hands before and after organizing family papers, photos and treasures. Heirlooms often have ingrained dust and your hands may have oil on them that can damage items. When handling photographs, wear white cotton or nitrile gloves to avoid leaving permanent fingerprint smudges on them. However, don’t wear gloves when handling papers, as gloves make it easier to tear them. Handle photographs and papers by the edges.

Stored textiles such as wedding dresses, heirloom quilts or baby clothes should be cleaned before storing them so they won’t attract moths. You can get special archival bags from dry cleaners. Clothing and textiles also can be stored in an acid-free box.

Storing valuables in a basement where air doesn’t circulate can make them prone to mold growth. Warm moist hair descends into basements and condenses on cold surfaces, eventually leading to mold.

Displaying items in shadow boxes or frames with mattes goes a long way toward protecting them from dust.

Do no harm

The more historic items are handled, the more chance they will be damaged. Handle them seldom and carefully. Never do anything to an old photograph that is irreversible, such as writing on it, repairing a torn section with tape, retouching it or laminating it or trying to pry it off a surface that it is glued to. Instead, take a high resolution picture of it and work with the copy.

Never place paper clips, staples or glue on historic papers or photos, as they will damage the items. Use copies, not the originals, for displays or to make memory books.

Store old photos in acid-free folders or archival polyester plastic sleeves and file them with an accompanying paper or acid-free label on which you have written the caption.

If you inherit multiple collections and have the option, keep collections of papers or photographs separate by family groups and note on the boxes or in a paper inside the box who you received the collection from and the date.

Tell the story

Without the story, artifacts are just things. That makes writing down the story associated with items a top priority in organizing them.

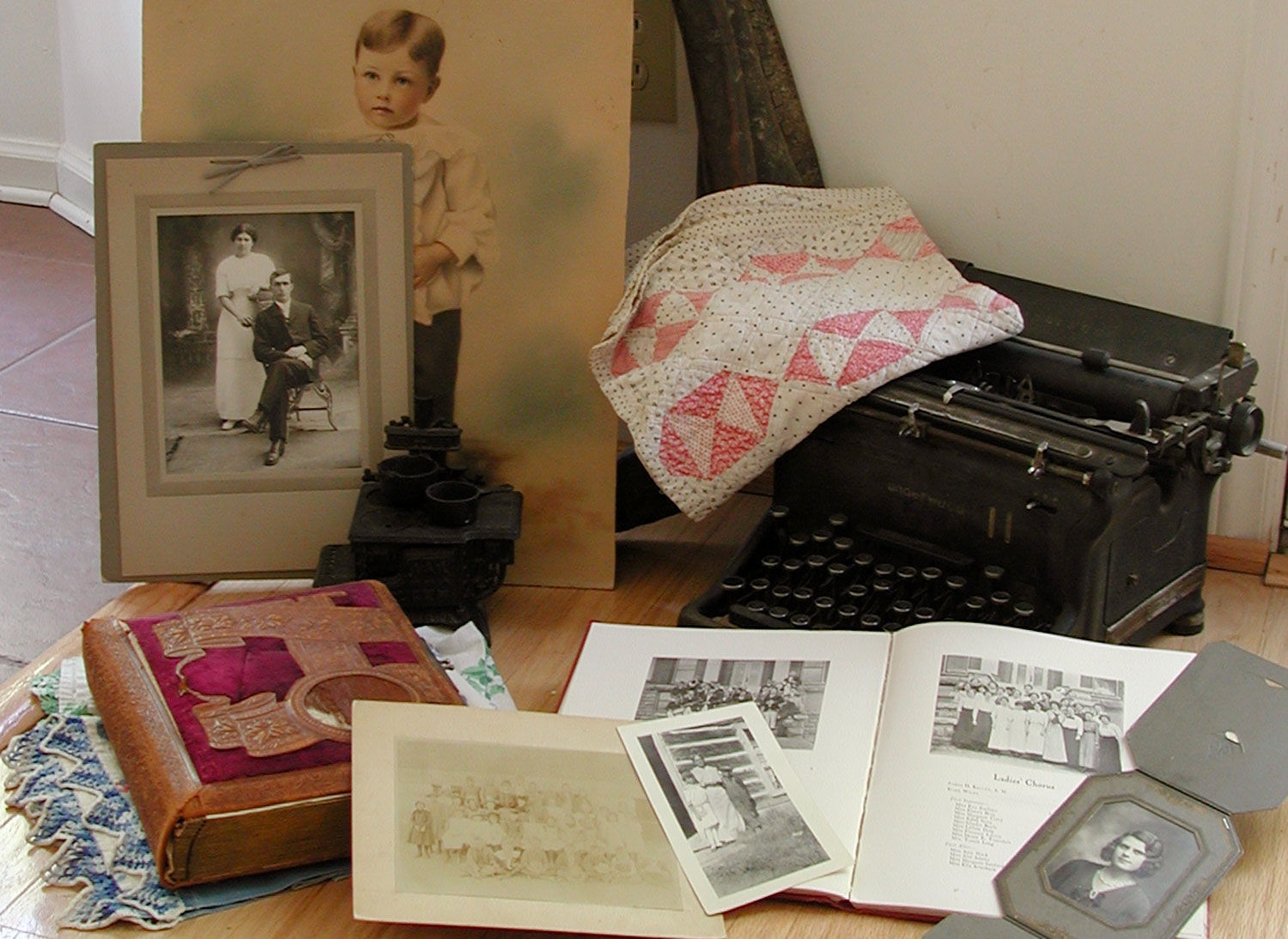

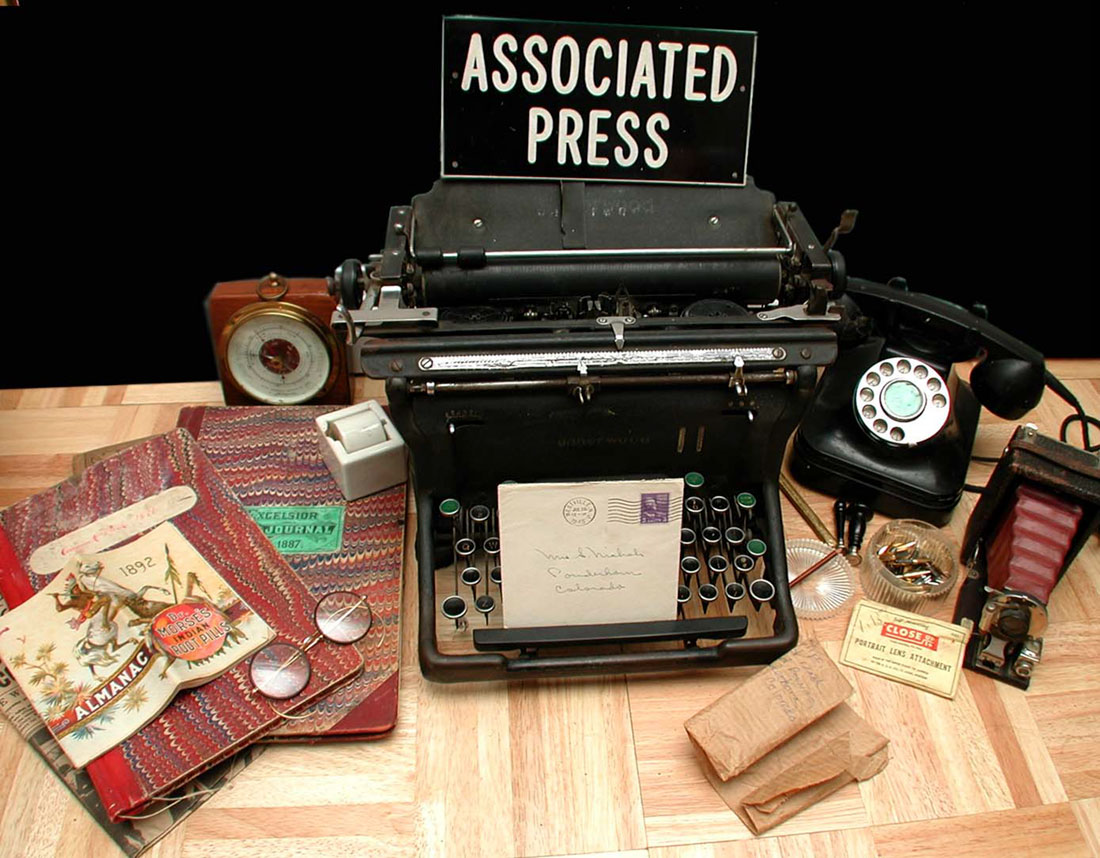

Old daily-use items, taken together, can tell the story of work in a pre-digital age.

These items are remnants of the work women once did in their homes - sewing, ironing with a flat-iron, cooking on a wood stove.

Store jewelry in a soft cloth bag and then a jewelry box, with a paper telling the significance of the item in your family history, who owned it, its age if possible and any other details associated with it, including locations.

Old books can be placed in archival polyethylene bags that are left unsealed and then stored in an acid free box. Alternatively, they can be wrapped in acid-free tissue and then stored in acid-free boxes.

Wrap silver in silver cloth bags to prevent it tarnishing and keep it separate from other family heirlooms such as papers, books, photographs and fabrics.

Keep a Backup in Case of Disaster

Make copies of family photographs and papers and store them in different places and on different media – your computer, an external hard drive or the cloud so you have backups in case you have a house fire, flood, burglary or other disaster.

Monetary Value

Most heirlooms don’t have a lot of monetary value, but some may. If you think you have a valuable heirloom, contact an expert to have it appraised and record the approximate value with the artifact in your inventory. Check with your insurance agent and make sure it is insured.

Ultimately, we need to keep family heirlooms to pass along the story of our family to younger generations. Here, my niece Maia Espinosa is wearing an antique feathered hat as she looks at a photo of her great great great aunt, who was among the first women voters in the United States.

Check out these related items

A Minimalist Tries Marie Kondo

A confirmed minimalist finds that Marie Kondo's tidying method helps her to refine an understanding of what brings joy.

Mantel from Reclaimed Wood

Making a fireplace mantel from a reclaimed log requires mounting it so the supporting wall will bear its weight.

Building an Arch and Cabinets

To carve space for our office out of a larger living space, we built an arch and cabinets out of old reclaimed beams.

Reclaimed Wood Gets A New Life

Japanese carpenters say that wood gets a new life when it is made into a new form. See some new of these new lives.

The History of Race in America

The racial history of the United States belongs to us all, with the responsibility to resolve the accompanying outstanding problems.