The History of Race in America

Photos by Forrest Anderson; historical photos and documents

“What a stupendous, what an incomprehensible machine is man! who can endure toil, famine, stripes, imprisonment or death itself in vindication of his own liberty, and the next moment be deaf to all those motives whose power supported him thro’ his trial, and inflict on his fellow men a bondage, one hour of which is fraught with more misery than ages of that which he rose in rebellion to oppose.”

— Thomas Jefferson, 1786

I spent several years working and researching as a historian in the South, delving into its history for clients who wanted books written about their families or business organizations. I didn’t set out to become a specialist on American racial relations. I didn’t have to – race permeates the American landscape, historical documents and culture.

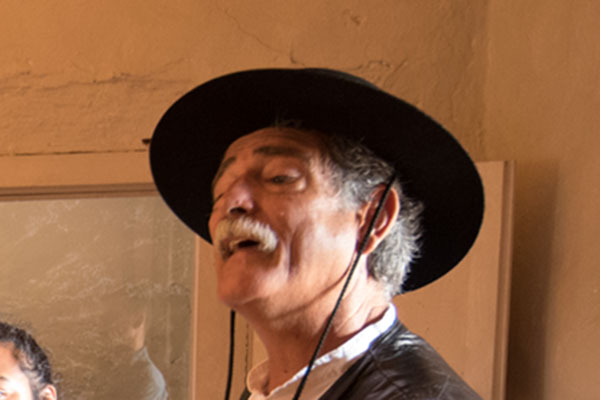

Me doing historical research at Bennett Place in North Carolina at a reenactment of the agreement ending the Civil War in that state.

My research stretched up the East Coast into New York, New Jersey, Maryland and Delaware and then West across the southern United States. It went far back into American history to the earliest traders, exiled criminals and adventurers who settled the Americas. It moved up the coast of California with Spanish priests who established missions and into New Mexico and Utah with Spanish explorers.

I came to understand that race is not a specialist topic. It is central to the identity of the American people and to understanding who we are as a nation.

The United States has never been a white country that gradually became racially diverse. Native American culture is varied, extensive and ancient – with nations such as the Cherokees and the Pueblos stretching back millennia before European Americans arrived in the Americas in the 1500s. The evidence represents many waves of migration by different peoples.

This display details the history of the displacement of Native Americans by land-hungry European Americans.

The first Africans landed on American shores in 1619. Asians came to the Americas in both pre-colonial times and later, with Chinese Filipinos settling in Mexico during the Spanish Empire and the first Filipino sailors landing in Louisiana in about 1750.

Racial diversity has shaped virtually every aspect of our history and culture and has been grappled with by every generation of Americans, as it is today.

Historians typically look at three factors to develop an understanding of the past – the physical landscape and remaining artifacts, written records, and the descendants of past peoples.

The Landscape

The story of America’s fraught racial relations is evident across its landscape, from Civil War battlefields, Southern plantations and port cities with ante-bellum mansions to towns founded by freed African Americans, forts, Native American ruins, sacred sites and reservations and Spanish missions and churches.

As historians, archeologists and others have turned toward telling the stories of these sites more inclusively and honestly, the history of race in the United States has emerged more fully.

Historic plantations that once presented a white man’s narrative of idyllic life in white-columned mansions landscaped with old cypress trees are now presenting accounts of the hard slave labor and violence that sustained those lands as profitable agricultural operations. Some also are telling the story of the system of bonded labor that developed after slavery was abolished. Plantations such as Boone Hall Plantation near Charleston, South Carolina, and the Whitney Plantation near New Orleans exhibit lists of names of people who were enslaved at those places as well as some of their stories and information about their culture.

A presentation on the influence of African American music outside one of the slave cabins at Boone Hall Plantation in South Carolina.

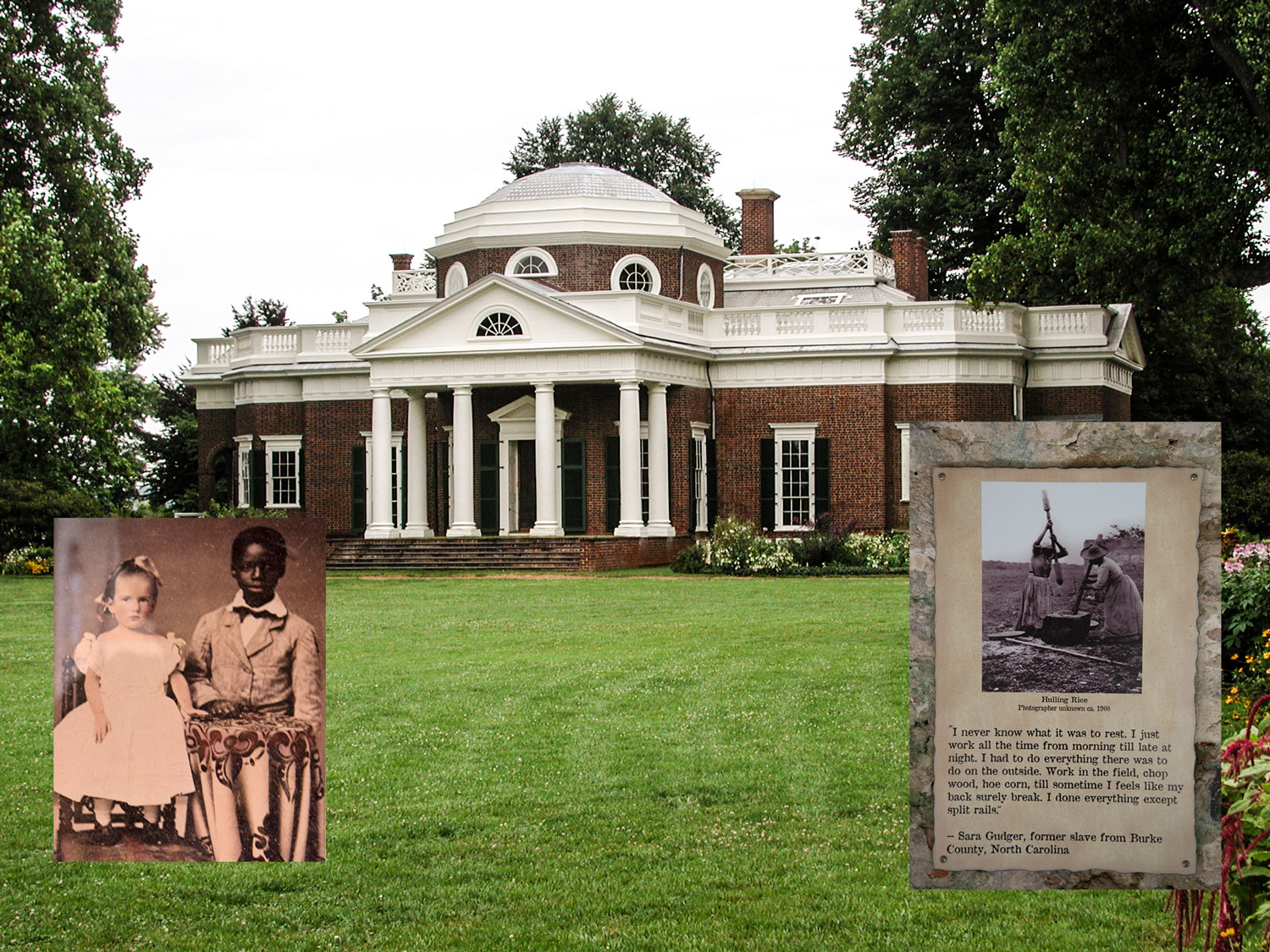

The slave quarters have been recreated at James Madison’s home in Montpelier, Virginia. Slave Sally Hemings’ quarters at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello have been recreated and the story of her relationship with Jefferson that produced six children is told there.

Historical sites and museums have mounted exhibits with statues or other depictions of individual slaves that tell the truth about slavery – the hunger, drudgery, whippings, rapes and fear of being sold away from family members. These efforts are helping to express the magnitude of the horror, loss and grief experienced by enslaved African Americans as well as the negative impacts that slavery has had since. Descendants of both slaves and slave owners have become involved in such efforts.

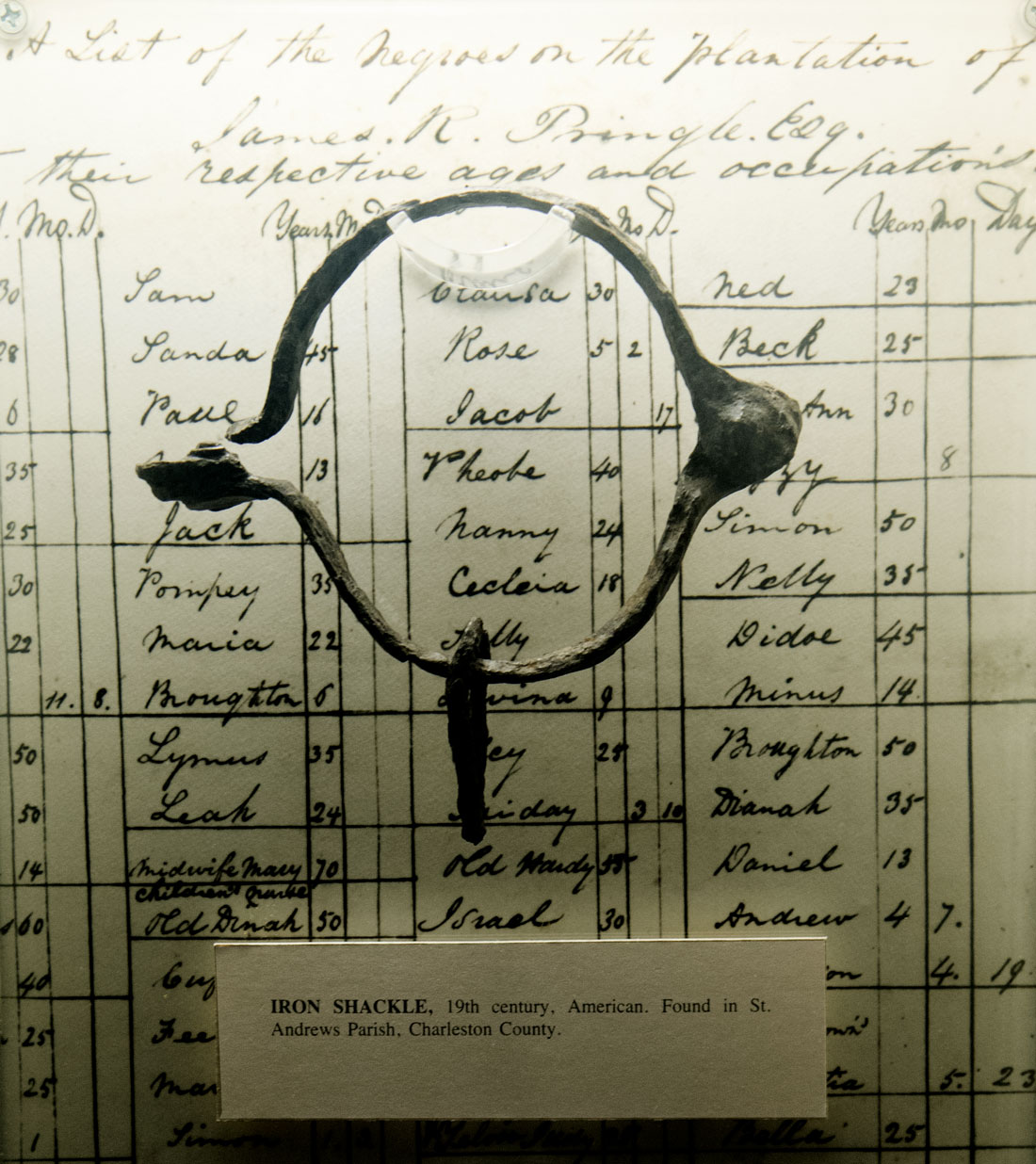

A list of enslaved peoples with an iron shackle at a musum in Charleston, South Carolina.

Iconic sites such as Monticello, Mt. Vernon, Montpelier and Williamsburg have opened the earth to archeological exploration and their archives to documentation of enslaved African Americans. The portrait of America’s founding fathers that has emerged has become far more nuanced and realistic. It is revealing the roots of America’s racial and income inequality.

Visitors to these sites now are told that Jefferson owned 600 slaves who worked Monticello’s 5,000 acres, that Washington owned 123 slaves, that James Madison owned more than 300 slaves at Montpelier and that more than half of Williamsburg’s population were enslaved. The White House has an on-line website detailing the lives of the more than 300 enslaved African Americans who built it and worked at it.

The reality that Jefferson wrote that “all men are created equal” and yet enslaved more than 600 of them boggles the mind, but he wasn’t alone. The majority of those who signed the Declaration of Independence were slaveholders, although some were avid abolitionists. This horrific incongruity troubles not only us but bedeviled many of slave owners, including Jefferson, Washington and Madison.

Jefferson publicly called slavery a moral depravity and “hideous blot” and thought it was the most significant threat to the survival of the fledgling United States. In 1778, he drafted a Virginia law that prohibited importation of enslaved Americans, and in 1794 he proposed an ordinance to ban slavery in the Northwest territories. He also thought, however, that emancipating slaves wouldn’t work unless slaveowners consented to do so together in a mass emancipation. He doubted that the federal government enacting emancipation would be successful and thought it would ignite a massive civil war that would destroy the fragile union. Jefferson’s views came to be used as an argument for perpetuating slavery as technological and agricultural advances made slavery more profitable. Except for Sally Hemming and her children, Jefferson never freed his slaves.

Both Jefferson and Washington discouraged cultivation of crops such as tobacco that were heavily dependent on large numbers of slaves. They favored moving over to other crops such as grain that needed little or no slave labor and both experimented with transitioning to such crops.

Washington’s views on slavery changed gradually. By the time of the Revolutionary War, he was questioning it. He considered it inefficient, as his profits didn’t cover the cost of feeding and clothing his slaves. His move away from tobacco to less labor-intensive grains left him with more workers than he needed, and he opposed selling them away from their family members.

His views developed along with growing antislavery sentiment throughout the Atlantic until by the 1780s-90s, he was stating privately that he didn’t want to be a slave owner, buy or sell slaves or separate enslaved families and that he supported gradual abolition of slaves. However, he, like Jefferson, believed that pushing the matter publicly could tear the new country apart.

“There is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do, to see a plan adopted for this abolition of [slavery] but there is only one proper and effectual role by which it can be accomplished, & that is by Legislative authority.” he said in 1786.

In his will, Washington ordered his slaves freed, including the immediate freeing of his valet William Lee who had handled his personal and camp equipment throughout the Revolutionary War. Washington freed him “as a testimony of my sense of his attachment to me, and for his faithful services during the Revolutionary War.”

James Madison’s views on slavery were similar to those of Jefferson and Washington. He described slavery as a stain on the ideals of the new republic and a national evil. He asserted that a slave was legally a member of society, not a mere article of property. He also was concerned that slavery was hurting the United States’ international reputation. However, he never pushed for abolition because he was concerned about the industrial Northern states pushing their values onto the agricultural South.

What are we to make of these men who lived in their comfortable mansions on the forced labor of hundreds of slaves in what were essentially concentration camps? Our founding fathers’ failure to act on slavery, despite the other great accomplishments for which we honor them, is a monumental flaw that lives on with us today in our own fraught racial relations. The omission of the mention of slavery in the U.S. Constitution was a deliberate moral compromise that John Adams characterized as a “fig leaf.” Adams and his son John Quincy Adams were the only two American presidents in a half century who didn’t own slaves. Slavery permeated daily life in Washington, D.C. Enslaved people worked in shops, drove carriages, and served white people at their tables, cleaned their houses and clothing and cared for their children.

Washington, Jefferson and other slave owners’ lifestyles set the bar for the ideal lifestyle impossibly high – fine china and food, servants, blooded horses and fine carriages, a large luxurious house and host of accoutrements that they actually couldn’t afford even with slave labor. Some of these luxurious aspirations live on today in our culture and continue to be at the core of current racial problems and income inequality. Try as we might, we can’t excuse this wrong away. We can only tell the truth about it and try to change the inequalities.

“It is better to offer no excuse than a bad one,” Washington said.

That slavery played a central role in the American Revolution is obvious. Resources for the fight and the building of the new government came from the labor of slaves.

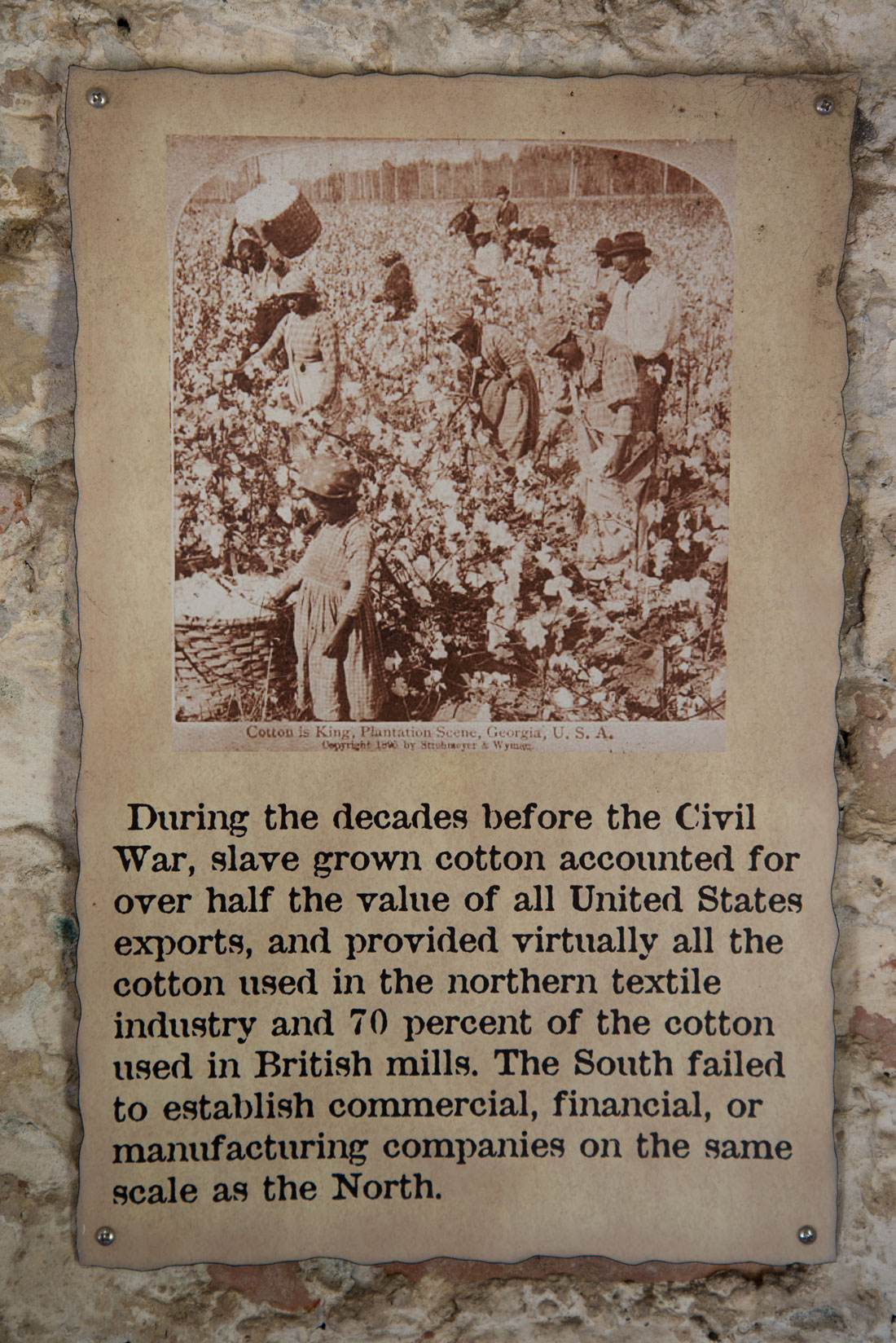

As historians have studied the economics of slavery, it has been clear that it played a pivotal role in the early American economy. It was not just a regional institution in the South. More than half of the nation’s exports until after the Civil War were raw cotton, almost all of which was grown by slaves. Many merchants in New York and Boston became wealthy on trading slave-produced agricultural goods. Slavery was the source of the cotton that fed the textile mills of the North, producing New England’s Industrial Revolution.

A sign on the wall of a slave cabin at Boone Hall Plantation in South Carolina, and, below, cotton growing at the plantation near the manor house.

Before the Civil War, the collective value of all of the nation’s slaves was more than the value of all other assets or businesses in the United States combined. Wealth was concentrated in the hands of major slave owners, who were massively influential in local and national politics. They served as presidents, Cabinet members, governors, legislators, judges, lawyers and doctors. They made laws and developed many of the nation’s institutions. Their children were educated at top universities.

The grave of John Rutledge, a slave owner and prominent citizen of Charleston who persuaded the Continental Congress not to abolish slavery, although his wife and other family members freed their slaves and became avid abolitionists.

Slave-produced cotton dominated the global economy and entire industries developed in ways that created jobs open only to white workers. Slaves were bought, sold, insured, rented, loaned, willed and used to settle debts. When enslaved African Americans were freed, European Americans retained land, jobs, educational and business opportunities and legal protections that African Americans were excluded from. This laid the foundation for the current problem of the median net wealth of white families being $171,500 while the median net wealth of black families is a tenth of that.

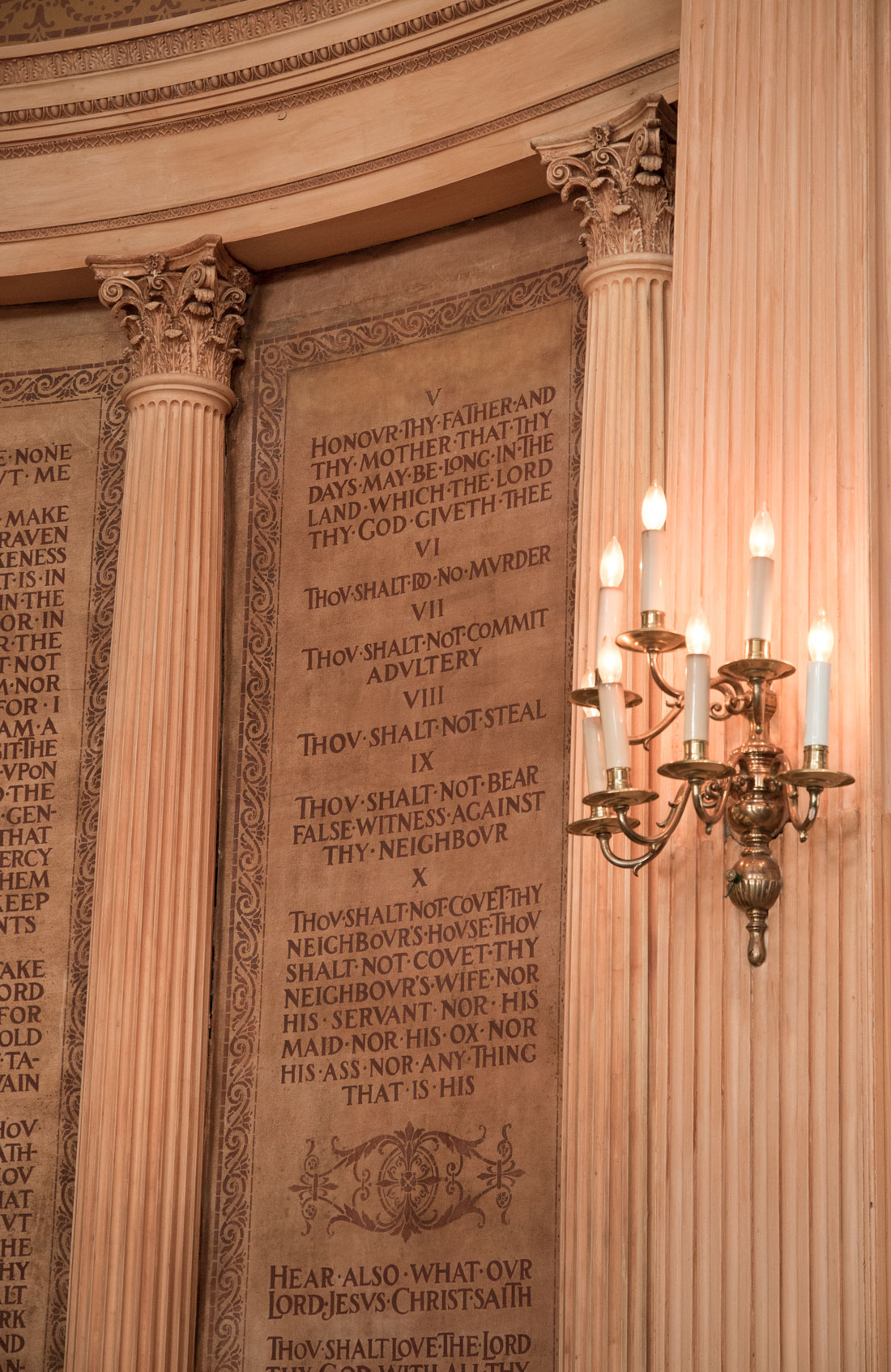

Nowhere is the central nature of slavery in the economy more evident than at Middleton Place plantation near Charleston, South Carolina. This area’s economy was heavily dependent not only on enslaved Africans’ labor but also their knowledge and genetics. Slave owners specifically purchased and imported Wolof rice farmers from what is now Senegal for their expertise in rice production. The farmers created lock and flooding systems to maximize rice growth in the tidewaters. Their bodies also had sickle-shaped cells which gave them increased resistance to the malaria that had scared slave owners away from the tidewater plantations of South Carolina. The Wolof farmers’ successful rice cultivation created an economic boom that made South Carolina the wealthiest colony in America for a time. Enslaved artisans built the opulent mansions that lined Charleston’s waterfront and the elaborate churches in which slave owners worshiped.

The Ten Commandments inscribed on a wall at St. Michaels Church in Charleston where prominent slaveowners worshipped.

Plantations are just one of the many places where slavery appears on the American landscape. University campuses once built by slaves are bringing their history out in walking tours, memorials listing slaves’ names and other initiatives. Museums that once brushed over African American history now have large prominent exhibits about it. Much more needs to be done to commemorate African American contributions to churches, financial districts and other sectors.

Further West, Native American historical sites tell the story of the suffering that native peoples endured as slaves to the Spanish as well as their contributions.

This Native American cemetery near Taos, New Mexico bears silent tribute to Native Americans who once were forced to labor for Spanish land owners in New Mexico. Taos was a trading center where Native Americans were bought and sold.

Both before and after the Civil War, another type of landscape was created – that of segregation. Separate churches for blacks and whites, neighborhoods, parks, universities and even towns arose. While many of these were removed after segregation, others remain. Some overgrown black cemeteries have been cleaned up and the gravestones in them found.

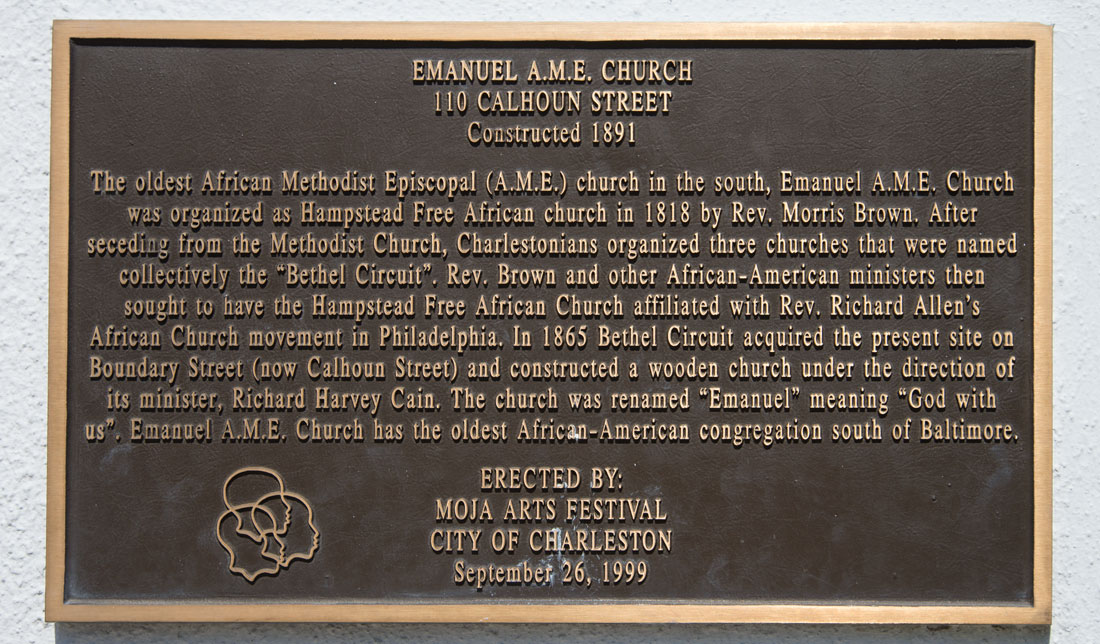

This plaque is on Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston, South Carolina, a major African American landmark and the site of a recent white supremist shooting.

Black colleges and universities founded because black students were prevented from attending other universities during the Jim Crow era are important historic sites. Some parks that originally were designated for blacks are significant partly because African Americans gathered at them for civil rights protests. Black financial districts were important places where black political leadership was cultivated.

How we interpret and preserve these sites is significant, as public spaces are venues for people to come together and resolve their differences and inequalities. That effort has become increasingly important in an era in which urban development has re-segregated many urban areas. Some cities such as Charlotte, North Carolina, are more segregated today by than they were in 1960. White children overwhelmingly attend charter schools, so that most students at public schools are black and brown.

Documents

As I pursued historical research, I was shocked by the enormous documentation of slavery, racial cruelty and exploitation revealed in public documents. Working in the National Archives, Library of Congress, and state and local archives across the United States, I found bills of sale of enslaved people, wills passing slaves to family members, and documents depriving Native Americans of compensation for their lands. Some were in envelopes that I’m reasonably certain had not been opened since they were first stored. Some looked so freshly penned that they could have just been written. Some of these documents reside in the papers of the most respected leaders of communities. Exploiting and abusing people clearly was not a disqualification from holding positions and receiving economic rewards in their communities. Some Native Americans were forced to make the long sad Trail of Tears trek to Oklahoma solely because they were Native American only to find this statu denied once they got to Oklahoma so that they couldn’t claim promised compensation for their lands and homes. In New Mexico, documents record the long slavery of Native Americans by the Spanish. Colorado documents are clear that land that European American settlers were granted had been owned by the Ute tribe. In California, Spanish mission records record the sad plight of Native Americans forced to work on Spanish mission lands.

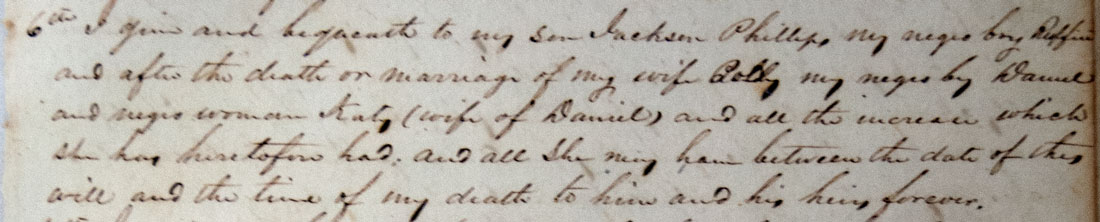

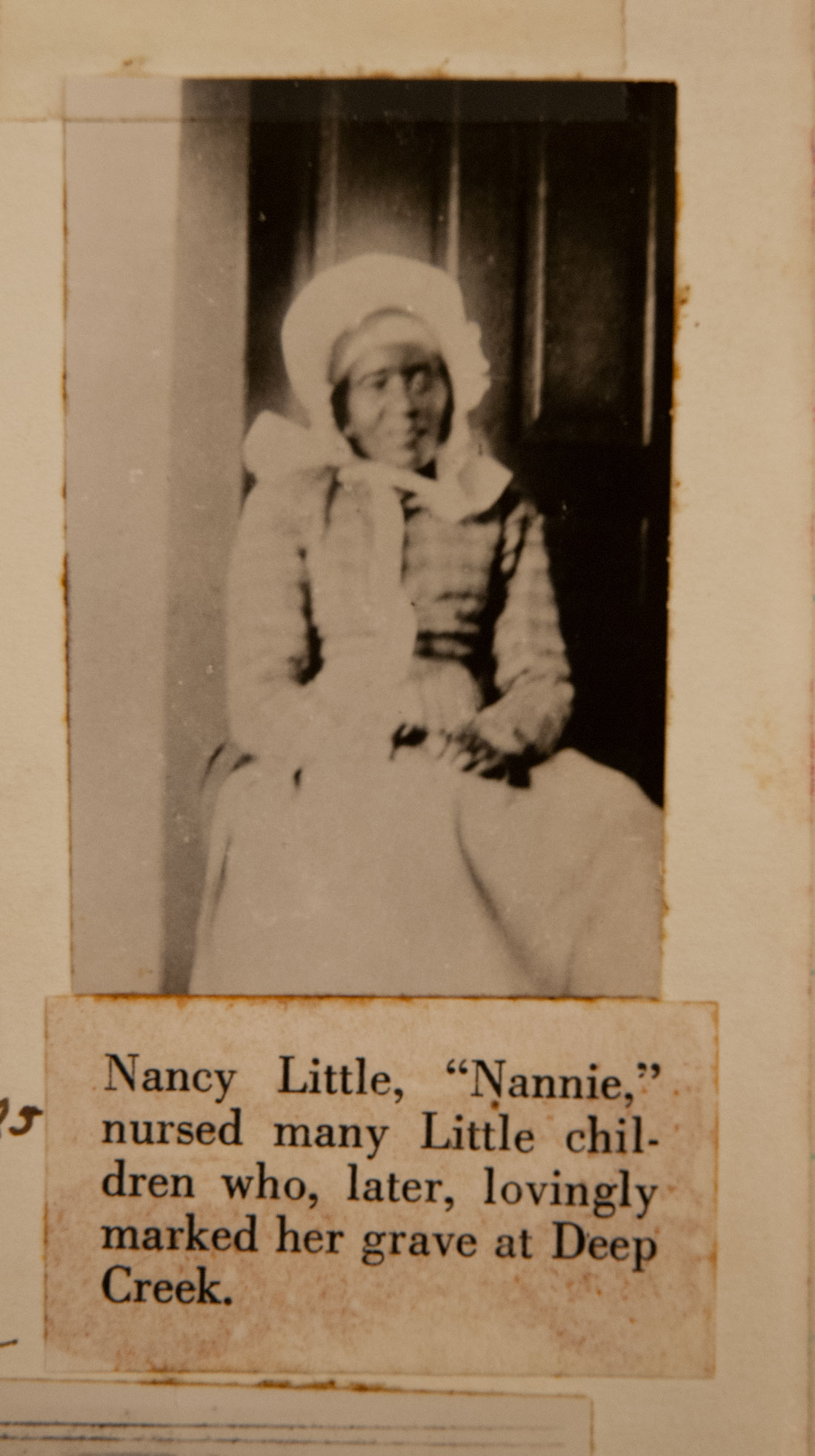

A will bequeathing enslaved people to a slave owner's family members. In the same family, a photograph, below, of a black woman who nursed several of the family's children. Slavery placed people in intimate contact with each other in households, creating deep and complex ties.

The exploitation the records describe is mentioned quite dispassionately and routinely in documents in which mostly white males sold, willed or otherwise disposed of or acquired people. There was no attempt to hide or soft pedal it. The national and state governments employed a large number of enforcers from courts and legislators to patrols, military officials and Indian agents to impose racially discriminatory policies. Their actions constituted major historical currents and events.

After the Civil War, many court and other documents record intimidation of African Americans and others to prevent them from exercising basic rights.

Reading these documents helped me to understand the magnitude and centrality of our historical problem with racism and how it is the history of all Americans, not just the history of minorities.

DNA

Among the most powerful modern avenues into the study of racism in the United States is DNA. One of its most important insights is that the concept of race is not accurate or useful in describing biological variations between people. Racial groupings such as white, black and Hispanic that we use and that are on our government forms are socially defined, not biologically based. They also are continually evolving as they reflect the way that we structure our society, do business, intermarry, reproduce and shift our identities over time.

That isn’t to say that genetic variations between groups of people don’t exist, because of course they do. The problem is that they are much more complex than the race labels we use and those race labels are not reflected accurately in genetics.

Unfortunately, these labels have been incorrectly used to reinforce races as genetic categories. Ancestry testing has been used to enable people to claim that they are a certain percentage of the five traditional “races” - African, European, Asian, Oceania and Native American.

This perception assumes that there is wide variation between the races and that individual races have a uniform genetic identity. This is not true. Human populations do cluster into geographic regions, but the variation between people in different regions can be small and the lines between populations blurred. Moreover, people in single regions can be quite diverse.

Scientists have found that the vast majority of alleles, or variations of a gene, are shared over multiple regions or even globally. Human beings are fundamentally similar. More than 92 percent of alleles are found in two or more of seven major geographical regions. There are not trademark alleles or genetic features characteristic of a single group but not present in others. Just 7.4 percent of more than 4,000 alleles are specific to one geographic region and they occur in less than 1 percent of the people in that region. There is no genetic evidence of groups we commonly call “races” having distinct, unique genetic identities. In fact, two people of European descent can be more genetically similar to an Asian person than to each other.

Human genetic variations do have a connection to our ancestors’ geographic origins, so with a person’s DNA, scientists can make a reasonable assumption about where that person’s ancestors came from. However, this focuses on how and where a person’s family history occurred, not a racial category they might fit into.

Classification of people into different races usually occurs because of visible physical features such as skin color, height, eyes and hair. Racial classifications also relate to culture, history, religion and economic/social class. Visual physical differences, however, are only a minute part of our genome. We all share 99.99 percent of our DNA. There is no evidence that these visual differences are connected with other traits such as intelligence or behavior. Thus, just .1 percent of variation between populations has been used to justify the history of racial atrocity.

Genetics unfortunately are being used by alt-right advocates to prove their white heritage and claim that Europeans and Asians have superior intelligence because they inherited larger brains from their Neanderthal ancestors. Neanderthals did have larger skulls than modern humans, but there is no evidence that would link that to intelligence or superiority.

We have our genetics primarily because of historical events that influenced our ancestors’ migrations and mating. Research is revealing that the DNA of modern African Americans reflects their ancestors’ troubled history.

The trans-Atlantic slave trade forced more than 400,000 Africans to the early American colonies and later the United States. There, they mixed with people of European ancestry. Usually this was because enslaved black women were raped by white men.

A study by researchers at McGill University in Montreal found that the majority of African Americans’ DNA comes from African ancestors, and virtually all African Americans also have European ancestry. Those living in Southern states have about 83 percent African DNA, while those living in other areas of the country have 80 percent DNA from African ancestors. African Americans outside the South tend to have a larger fraction of European DNA.

Scientists can break up a genome chronologically to determine when someone’s ancestry entered the gene pool because blocks of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) shorten over time at a consistent rate. The research has shown that most European DNA among African Americans today probably entered their gene pool before the Civil War, when the vast majority of African Americans in the United States were enslaved in the South and it was common for African Americans and European Americans to mix. This dropped off sharply after the war. The clear implication is that sexual exploitation of African slaves by European Americans was widespread, particularly since the genetics indicate that the African side of the equation typically was female and the European side was male.

U.S. slavery was a subset of a much larger system of slavery that also included the Caribbean, Central and South America. Similar studies have been made of the genetics of people who have ancestry in the Caribbean. Researchers studied the DNA of 251 people in Florida who had Caribbean ancestry and residents of Venezuela who belong to three Native American groups. They also compared them to global DNA databases. The research indicated that few Native Americans survived the European arrival and colonization – the native population of the Caribbean collapsed within a generation of Christopher Columbus’ first visits to the Americas and the arrival of other Europeans. This is unlike the gene pool on the mainland Americas, which shows a more significant continuing Native American influence. The study showed that Native American genes were replaced by characteristically African SNPs during two phases of the trans-Atlantic slave trade – the first of people from the Senegal region of West Africa and the second larger one of people from near the Congo.

Historical documents also reflect that the initial phase of the slave trade began around 1550 in which slaves were mostly taken from the Senegambia area of the Mali Empire which includes modern-day Senegal, Gambia and Mali. This made up 3-16 percent of the Atlantic slave trade. A second period which comprised more than half of the trade involved slaves mainly from Nigeria, Cameroon, Gabon and the Congo.

Again, the studies found that Native American SNPs were more prevalent on the X chromosome than others, reflecting the Caribbean history of Spanish colonizers both marrying and raping Native American women.

The genetics help fill gaps in historical records. While shipping manifests document the movement of slaves from Africa to ports in the Americas back as far as the early 1500s, there is little information about what happened to the enslaved peoples after they arrived in America. The research indicates that genetic differences among people of African descent living in different regions of the Americas closely matches information in the ship manifests.

Brazil and other South American regions have higher proportions of people with Congolese ancestry, while Central America has more people of Senegambian ancestry. This is reflected in the historical records of the two phases of the slave trade and departure ports, shipping routes and destinations.

The other great African American migration was in the early 20th century when many left the South during the Jim Crow era. The researchers have found strong genetic connections between African Americans in the South and those in the Northeast and Midwest, and the genetic similarities tend to cluster along the train line that African Americans took in leaving the South during the Jim Crow era. Among the prominent lines were the Illinois Central to Chicago and the Atlantic Coast line. The research has enabled the creation of a detailed map of genetic variations in African Americans that can help show how genes influence the risk for various diseases.

The Jim Crow era produced its own set of evidence, which still shows up in such bizarre aspects as old train stations and other buildings in the South that have four restrooms so that each race could use two; in schools and parks that were once segregated; in mountains of documents; and in the DNA of African Americans.

The studies show that the average African American has 1.2 percent Native American ancestry. It appears in tiny chunks, indicating that most mingling between the two groups occurred in the early 1600s soon after the first slaves arrived in the American colonies.

The European DNA in African Americans occurs in slightly longer chunks, indicating a more recent origin that probably reflects the decades before the Civil War.

Researchers have estimated that 3-5 percent of people who identify as white have 1 or more percent African ancestry, with people living in the South having the highest percent. One in 20 people in South Carolina who identify as white have at least 2 percent African ancestry. In many places in the South, about 10 percent of people who identify as white have African ancestry.

So what about slave owners? If you are of European ancestry that goes back into U.S. history, how likely is it that your ancestors were slave owners who also produced African American descendants?

Recorded information on the number of slave owners over time is incomplete. The best source is the 1860 census, but by that time, many states had banned slave owning. In slaveholding states, the census indicated that almost 25 percent of households owned slaves. However, the percentage varied greatly by state. Almost half of families in Mississippi owned slaves and 46 percent in South Carolina did. The percentage was much lower in border states – 3 percent in Delaware and 12 percent in Maryland. Nationwide, some 7.4 percent owned slaves nationwide. Most slave owners averaged 10 or fewer slaves but owned slaves over generations, with many opportunities for sexual exploitation of enslaved women.

It’s fairly unlikely that if a European American’s ancestors were from the North, they owned slaves unless it was in colonial times. It’s much more common for slave-owning ancestors to be southerners. A common southern pattern is for an ancestor to have immigrated from Europe during colonial times and then received bounty land grants in the South in the 1700s and early 1800s. Later generations moved west as Native Americans were forced off their lands and the lands were ceded to European Americans. They took their slaves with them.

My experience in doing Southern research has been that many people didn’t own slaves but that most families whose history I researched do have some lines that included slave owners. Having slave owning ancestors obviously raises the possibility that you are related to African Americans who share ancestors with you. Coming to the Table, a program sponsored by the Center for Justice and Peacebuilding at Eastern Mennonite University in Virginia, encourages the descendants of slaves and slaveowners to come together to discuss their mutual history and try to heal. A number of historical sites have similar programs and some such families have held family reunions, conducted research together and provide scholarship programs for descendants.

So what can we conclude from this? The point is that we are all in this together, quite regardless of our own willingness or unwillingness to get involved. This is our collective history. Like Washington, Jefferson and the other founding fathers, we will leave behind the positive or damning evidence of whether we have tried to rectify the problem of race-related inequalities and its accompanying economic and social injustices or, like them, carry them into the future by our unwillingness to take a stand.

What will count will not be what we say, but what we actually do on the landscape, in the documents and with the people with whom we interact. That will determine whether the foundation of democracy and equality that we claim to uphold makes a difference to all people within our borders.

Check out these related items

Getting A Vaccine against Racism

A mother of non-white children compares her fears for her children because of COVID-19 and her fears for them because of racism.

The Racism of Confederate Statues

The racist past associated with the Confederacy and Confederate monuments has a complex history.

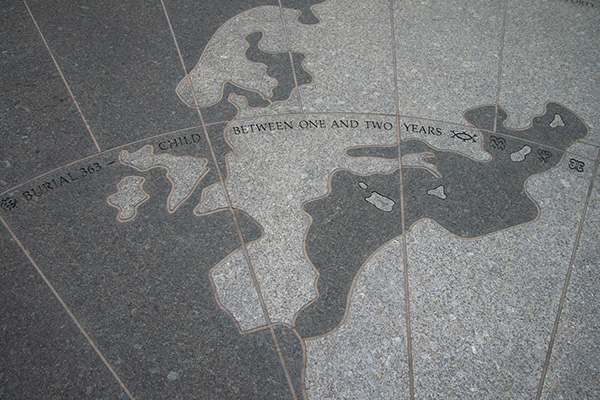

Memorial to Once-Forgotten People

A moving monument and burial ground in Manhattan comemorates enslaved people who once made up more than a third of New York City.

Wolf in Ship’s Clothing

The picturesque town of Bristol, Rhode Island, once was a slave port and home of the nation's leading slave traders, the DeWolfs.

What does it mean to be Hispanic?

What does it mean to be Latino or Hispanic in the United States? This blog explores the ambiguous origins of these two terms.