The Racism of Confederate Statues

Photos by Forrest Anderson

Across the southern United States in front of county courthouses, state capitols and in public squares are hundreds of monuments honoring people who fought against the United States government in the Civil War.

Just eleven states participated in the war, but Confederate memorials are found in at least 30 states. Since George Floyd’s death on May 25, some of the most prominent have been pulled down by protesters fed up with the white supremacy at the Confederacy’s core or taken down by local governments.

Such statues have long been a ubiquitous feature of southern towns, standing amid mounted cannons on the lawns of courthouses and state capitols or in public squares and parks. In smaller towns, they tend to be mass-produced depictions of an anonymous soldier, while in cities they often depict Confederate leaders such as Generals Robert E. Lee, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, Confederate President Jefferson Davis or other prominent slave owners. Some borrow figures from Roman or Greek mythology. They are standard stops in walking tours of historic districts associated with the Civil War, lending the impression that they were erected during or shortly after the war.

A Confederate monument in Raleigh, North Carolina.

These monuments are highly problematic for a number of reasons:

1. They tell only the pro-Confederate, white elite side of the story and were placed with no input from African Americans, who saw those honored by the statues as having fought to keep them enslaved.

A black and a white child play around a monument to the Confederates who defended Fort Sumter in the early days of the Civil War. The monument wasn't put in place untilt more than 70 years after the war. It depicted a one-sided white elite version of the war, invoking the imagery of ancient Greek and Roman triumphal statuary.

2. Most of these statues were erected long after the Civil War between the 1890s and 1950s, the former period marking the enactment of Jim Crow laws that stripped blacks of political rights and installed racial segregation and the latter period being marked by a backlash against protests aimed at restoring black civil rights. Such memorials thus celebrate not just the Confederacy, but the reassertion of white political power after a brief post-war period when blacks had civil rights. One point of the monuments was to send a signal that white supremacy was again in charge.

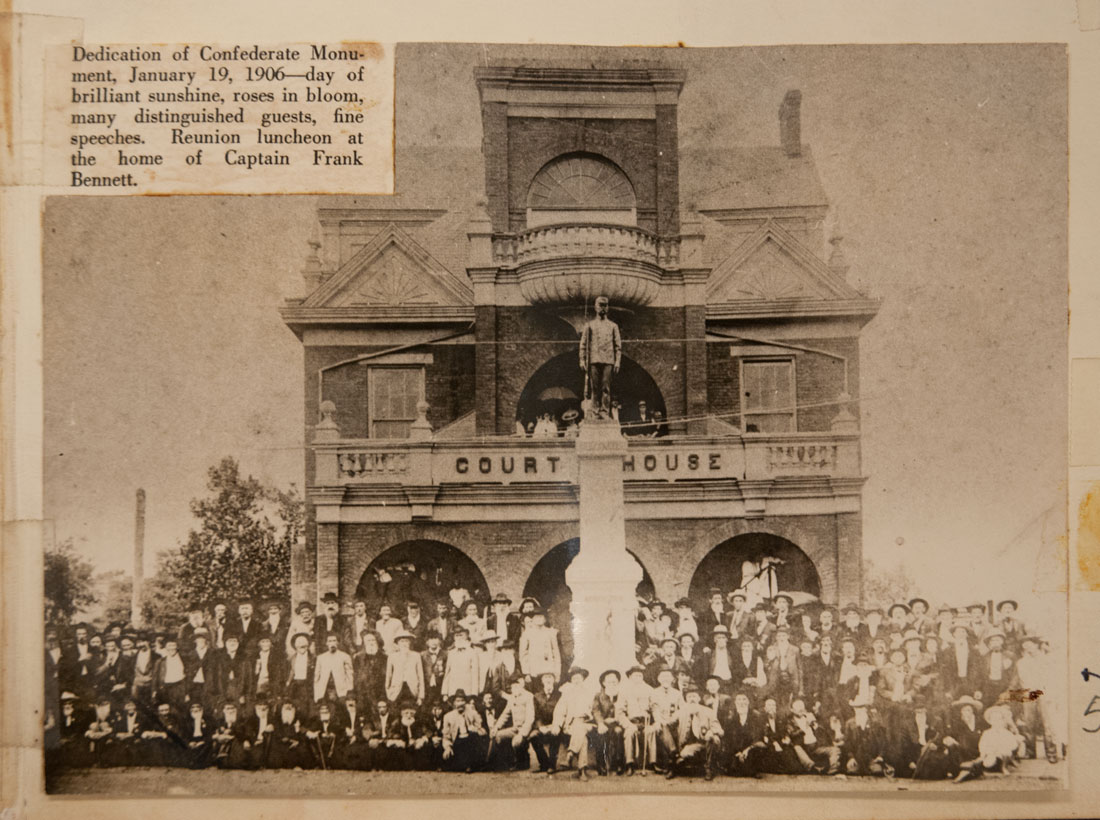

A 1906 photo of the Confederate monument in front of the Anson County, North Carolina, courthouse when it was installed.

Many of the subjects depicted in the statues carry arms and are associated with the political authority inherent in the nearby public buildings, projecting an implicit message of official legitimacy and authority. This impression is made although most were not erected by governments and don’t represent them. Placing such monuments in front of government buildings sent the message that white supremacy would prevail when blacks had dealings in such public spaces. The statues were a visual symbol of the inequality in the American justice system. The enduring appearance of the monuments reinforced a sense that these inequalities were permanent.

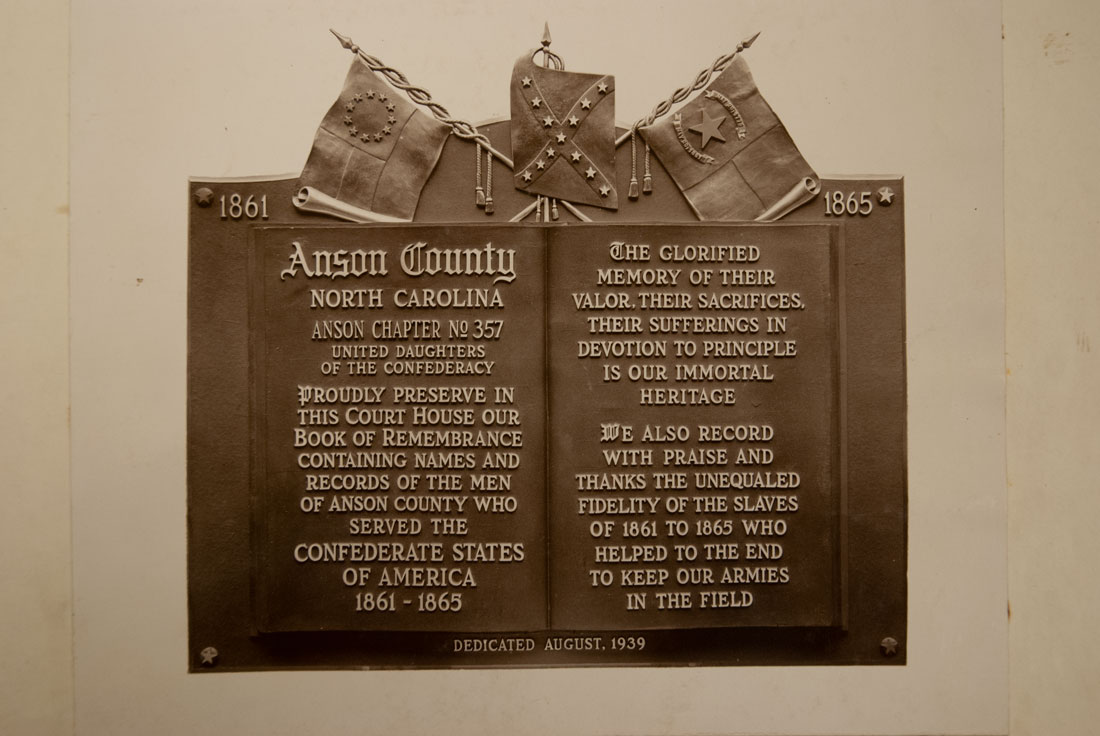

The statues are the visual and structural evidence of a much larger white supremacy movement. Often not far from the statues is a local library or historical society in which large, ornate memorial books about local Confederate martyrs have pride of place. The books, like the statues, were the projects of white women’s organizations such as the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Absurdly, this organization installed many monuments and markers in states that weren’t involved in the Civil War or didn’t even exist as states at the time of the war. Local reenactment groups, with men in gray Confederate uniforms and women in hoop skirts, do living history performances for school children and on patriotic holidays in the shadow of such monuments.

A dedicatory statement on a book of remembrance for Anson County, North Carolina. The book glorifies the soldiers' valor and their slaves' loyalty, a key theme of the white supremacy movement.

5. The statues are immensely emotional for both blacks and whites. For white families who lost soldiers in the Civil War, among whom were many whose fate was never discovered, the grief was devastating and spanned generations. It also was widespread in states with large death tolls. Many areas of the South never fully recovered from the shock, which left an entire generation of widows and evolved into a regional grief and grievance mentality mourning the loss of a pre-war way of life that only a privileged minority actually enjoyed. This still is part of Southern and, by extension, American culture. Many white Southerners and other Americans trace their ancestry to people who fought for the Confederacy and many own Civil War-era artifacts that belonged to those ancestors. They bury their dead near Civil War ancestors in cemeteries once segregated into black and white sections. I have met Southern farmers whose farm laborers are descended from enslaved people who once worked the same land.

The monuments were deeply disheartening for African Americans who had harbored great hopes when slavery was abolished and found themselves still in a white-dominated environment that denied them basic rights that they needed to live happily and safely. With a handful of exceptions, African Americans are absent from Civil War monuments. They also were ignored or minimized at many museums, house museums and plantation historical sites, at which guided tours made almost no mention of the enslaved people who once built, lived at and maintained the sites. It was as though once they could no longer enslave African Americans, whites sought to erase them from the historical landscape or recast them as having slavish loyalty to their Confederate masters.

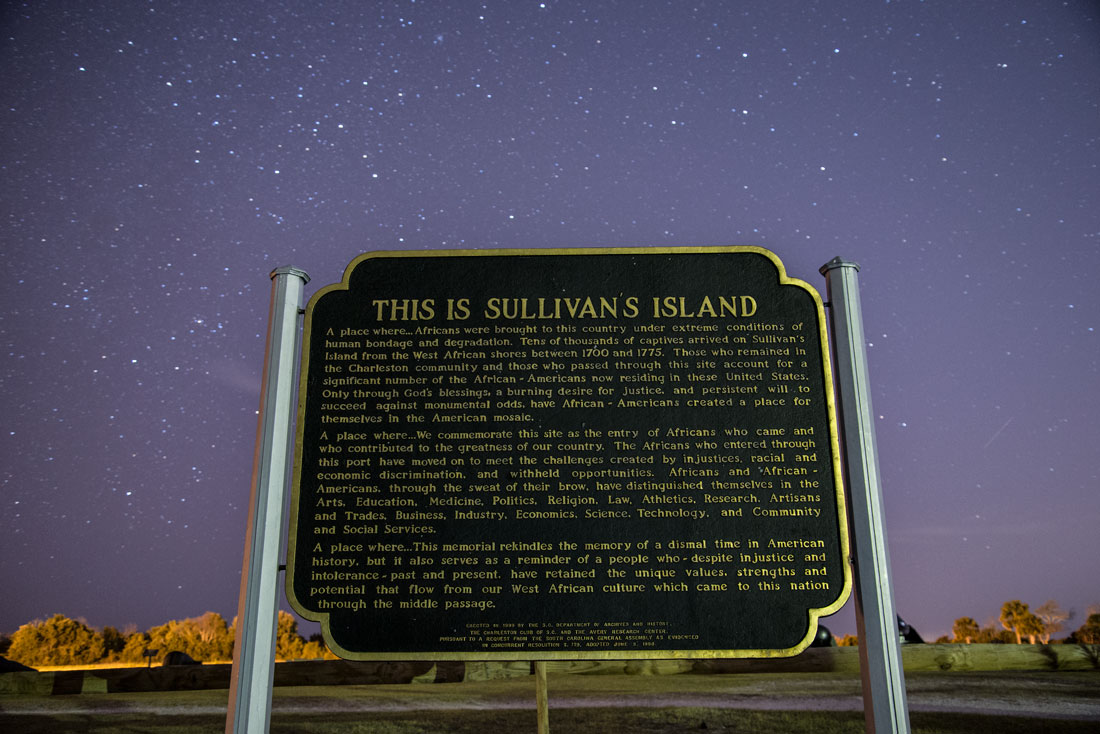

Charleston, South Carolina, removed a statue of former U.S. vice president and slaveowner John C. Calhoun, an ardent believer in white supremacy, on Wednesday. It is one of a number of Confederate memorials in the city. Meanwhile, the city until recently had only a simple board commemorating the place where thousands of enslaved Africans entered the United States through the Charleston port, the country’s African American Ellis Island. This abominable neglect of 40 percent of the enslaved Africans who entered the United States belies the argument that Confederate monuments should be retained for the sake of historical accuracy. Those who argue that removing the monuments erases history are too late – the South has already spent more than 150 years erasing the history of blacks on its landscape.

This board was for years the main tribute to the enslaved Africans who entered the United States at Charleston, South Carolina, and were sold at Charleston slave markets. They represented 40 percent of the enslaved peoples who came into the United States. A museum is now being built to tell their story.

6. The monuments have created two versions of cities’ histories, a romantic Lost Cause myth of the Civil War that often makes it into tourist brochures and onto postcards, and a legacy of slavery, segregation and economic and political inequality. Cities that depend on the perennial tourist interest in this romantic history of the Civil War have been reluctant to remove artifacts that celebrate that history. The Civil War and plantation history are big business. After all, what could be more romantic than a destination wedding at a plantation historic site? However, the cost of keeping the Confederate statues has risen as they have increasingly come to be seen as hated symbols of racial oppression. When Birmingham, Alabama, removed a Confederate monument in violation of a state memorial preservation act prohibiting such removal, the city’s mayor observed that it would cost the city less to pay a $25,000 fine for removing the monument than to deal with racial unrest associated with it. This raises the question – is the United States finally beginning to recognize the high cost of racism?

The answer for many communities and public institutions is yes. Since the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, Confederate monuments have gradually come down, at least 140 of them in the past four years. A statue of Jefferson Davis was pulled down by protesters in Richmond, Virginia, on June 9 and the Robert E. Lee statue there has been slated for removal by the state. Many Confederate names of parks, streets and school mascots have been changed. However, some 1,500 symbols of the Confederacy remain in public places. From place names to Confederate flags, the American landscape is replete with homage to a government built on the defense of slavery. They include relics or names placed as recently as the 1970s during backlashes against desegregation. The process of dismantling the Confederacy’s symbols has picked up speed as public opinion has migrated toward viewing the statues as repugnant. In some communities, city councils’ votes to change names or remove monuments have been seen as a no-brainer, while in others opposition has been so fierce that the statues had to be removed at night by masked crews under police protection. Pro-monument protesters have held armed vigils to protect some statues from removal.

Despite the fact that the Confederacy was a rebellion against the United States, it is now seen by many as deeply intertwined with the notions of patriotism. Patriotic displays in the South often include re-enactors in gray uniforms and women in hoop skirts. To revere the Confederacy is to be patriotic. President Donald Trump has tapped into this sentiment in his defense of Confederate monuments, rolling it into his Make America Great agenda which emphasizes making it great for white people. In this scenario, blacks are not participants in the American dream and have no place in patriotic events. The concept of freedom reverts to the old argument of the Revolutionary War – is our definition of freedom equal rights for all or privilege for ourselves at the expense of others’ rights? These two definitions permeate American history and survive today in the debate over Confederate monuments. Key disagreements as to whether the Civil War was fought over slavery (i.e. preserving oppression) or over rights (standing up to the federal government) are significant blocks to intelligent public discourse on the topic. This is so despite the overwhelming historical evidence that the states that seceded did so explicitly to preserve slavery in the face of an international movement to abolish it.

Patrriotism is intertwined with symbols of the Confederate flag in a display case in a museum gift shop in Richmond, Virginia. Throughout the South, Confederate and patriotic symbols and traditions intermingle.

Only after the war was the alternative narrative created of the Lost Cause to which Southerners were devoted, including the notion that the Confederacy had brilliant generals who were not defeated on the battlefield but overwhelmed by oppressive Northern might. This narrative insisted that the war was not about slavery but independence and the preservation of rural agrarian civilization in the face of urbanization and industrialization.

After Robert E. Lee died, a legend about him arose promoting him as the hero who had fought to preserve his home state of Virginia. In this view, Confederate General James Longstreet, who after the war joined the northern Republican Party and later used black and white officers to defend New Orleans against aggression by the white supremacist White League, was the villain. The narrative claimed that Lee lost the Battle of Gettysburg because Longstreet betrayed him, which isn’t supported by historical evidence. The Lost Cause arguments morphed by the 1890s into the claim that slavery had benefited both masters and their slaves, and freed blacks couldn’t handle emancipation. It was on this argument that the Jim Crow laws were based. When people question why monuments were built to the losers of the Civil War, they don’t realize that the monuments actually celebrated not the war but the later quelling of black rights.

As part of the white supremacy movement, museums and historical sites were created that sanitized slavery and the war and portrayed the Confederacy as a righteous homeland defender against an oppressive invader. The stereotype of the idyllic plantation with singing contented workers in the fields, a white columned mansion and soft-spoken women in colorful hoop skirts became the image of the South. This although most of the region was small farmers, some of whom owned a few slaves, and many plantations were forced labor camps run by overseers with no façade of mansions and carriages to mask the brutality.

The white supremacy movement of the early 20th century changed the way the war was understood and continues to affect the way that it is presented in schools and textbooks and seen by tourists to historic sites to this day. In the public imagination, Lee was the white-haired courtly gentleman and Stonewall Jackson the swashbuckling dare devil of the war while northern generals are portrayed as butchering thugs. There is a huge gap between this perception of the Civil War, in which there was plenty of butchering on both sides, and the historical evidence.

7. Many people who don’t consider themselves racist still are tolerant of Confederate symbols, although this is changing. When we moved to the South a little over 20 years ago, a hoop-skirted re-enactor blanched, stammered uncomfortably and passed me up to her “commander” when I casually asked her if her group would accept members like me even though I have an ancestor who fought for the Yankees in the Civil War. The biggest challenge in doing Civil War battle re-enactments at that time was that no one in the area wanted to fight on the Union side. A decade later, many re-enactors were casually changing sides and uniforms as they were recruited at battle re-enactments and many said they enjoyed re-enacting as a pastime but had no strong feelings either way about the war. One of my most interesting encounters when attending a re-enactment was with a young man in a Confederate uniform who was there with his hoop-skirted Hispanic girlfriend. Neither of them saw anything incongruous in their participation in an event that commemorated a government that would not have accepted her as a full-fledged citizen. In the intervening time, there has been an increasing public awareness that symbols do matter, as evidenced by protesters’ demand for their removal from public places and the U.S. military’s decision to rename installations that had been named for Confederate leaders.

Confederate monuments are a subset of a much larger group of monuments to white supremacy and colonialism and the inequality associated with them, as demonstrated when the George Floyd protests spread beyond U.S. borders. Statues associated with racism have been removed in England, Belgium, New Zealand and other countries, including those of people who profited from the slave trade and of Christopher Columbus and other colonizers who abused indigenous people. Statues of Christopher Columbus, incidently, also were a popular feature of the 1890s. This period through the first half of the 20th century was a major low point in racial relations. It’s no accident that Confederate monuments went up at almost the same time as the overtly white supremacist statue of a muscular President Theodore Roosevelt on a horse flanked by a Native American and an African who were walking. The message of this monument outside the Museum of Natural History in New York City was that a white man was in charge and those of other races were just stereotyped subordinates. Amid the Floyd protests, the decision to remove this cringey statue has been made.

The Theodore Roosevelt monument in New York, which has been set for removal.

The movement has illuminated a global problem with the shelf life of monuments – they are erected to honor prominent leaders who later come to be viewed unfavorably as oppressors. The original intent to honor a conqueror turns negative as the cost of their conquest becomes apparent in later generations. This is an ancient phenomenon. Busts of the Roman Emperor Caligula were once erected throughout the Roman Empire, but now are symbols of a mercurial, unhinged ruler. And so it goes globally and throughout time.

The emperor Caligula, whose image became associated with capricious and cruel rule.

Many have questioned why the United States can’t be more forthright in its handling of slavery, citing the German handling with the Nazi past as a model. The two aren’t exactly analogous, since the Nazis held power for a blink of an eye compared to the hundreds of years during which slavery was the foundation of Southern economy and culture. Exactly how far the United States should go in expunging the evidence of its pervasive racism and how it should do so when it permeates the entire historic landscape is an immensely difficult question upon which there is little agreement even among historians.

In some countries, replacing even the more recent past has been highly problematic. Russians pulled down many Communist monuments when the Soviet Union disintegrated, but still struggle with what to do with Vladimir Lenin. Former Chinese ruler Mao Tse-tung, whose image in statues, monuments and gigantic paintings was once ubiquitous throughout China, was largely discredited after his death by a China bent on opening to the outside world, modernizing and initiating capitalist style reforms. Most public images of him were removed, but some were retained along with the official narrative that he was the great founder of Communist China. The motivation was to avoid a wholesale trashing that could topple China’s entire political system and plunge the country into chaos. Like the Confederacy in the United States, Mao is still dragged back into public view whenever China’s leaders find him useful to their current agenda.

A statue of former Chinese leader Mao Tse-tung in Shenyang, China, looked incongruous next to the construction cranes that filled the city as it sought to recover from the effects of Mao's no-growth policies.

France is notorious for its difficulties in balancing democracy with its history of a repressive monarchy and religious structure. During the French Revolution of 1789, monuments to French kings were pulled down and churches desecrated. The country later backtracked, even erecting new monuments to beheaded monarchs Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette and reopening churches. Since then, France has swung back and forth between constructing elaborate new monuments to emperors and to republican heroes.

French revolutionaries beheaded King Louis XVI and his wife and discarded their bodies, but within a few years, a new regime rethought it and had statues created in their honor. However, they were consigned to a church that was made into a royal mausoleum, a safe place for past tyrants. A cult developed around Marie Antoinette that has similarities to the Lost Cause.

Throughout the former British empire, monuments to kings and queens and place names in their honor persist, despite colonialist and often racist connotations. Britain’s history of racism is as checkered as that of the United States, with both bloody oppression of people of color and abolition of slavery. Some of the most prominent British statesmen, such as Winston Churchill, were known as boosters of white supremacy and colonialism. The British and French empires also carted home monuments of past rulers of ancient civilizations and display them in showcase museums, where their appropriation has come to symbolize colonialism in countries where such artifacts originated.

Millions of people from all over the world, including former British colonies, annually visit the Queen Victoria statue outside Buckingham Palace in London. The British built similar monuments in other places in their empire, idealizing their colonial rule.

It is the rare country that doesn’t have to grapple with such unsavory aspects of its past and their continuing impact on the present.

The United States has always had its own problem with its founding fathers and early presidents, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson having been slave owners and Andrew Jackson having been responsible for oppressing Native Americans. Many other historical figures made significant contributions to the United States but had racist views. What to do with their monuments? How far should we go with this purge? And where should old monuments go to die when the ideologies upon which they were based are discredited?

The Jefferson Memorial to former U.S. President Thomas Jefferson in Washington, DC. The question of what freedom means and to whom it is extended has been a perennial one since the beginning of the United States. Jefferson was among 12 U.S. presidents who owned slaves. One of them was Ulysses S. Grant, who owned a single slave but later fought to destroy slavery and said his views on slavery changed so that he no longer thought it was moral for one person to own another.

A woman in a Muslim hijab passes a statue of George Washington in New York City. Washington, who was a large slave owner, probably would have defined freedom somewhat differently than this woman.

This statue outside the old State Capitol in Raleigh, North Carolina, honors three former U.S. presidents who owned slaves. James Polk favored buying enslaved children away from their families so that he could get more value out of their labor over the years than he could have had he bought adults. Andrew Jackson played a major role in the surpression of Native Americans as well as owning blacks. Andrew Johnson was a smaller slave owner.

These presidents, titans who pioneered the beginnings of American freedom, nonetheless interpreted it much more narrowly than the majority of us do today. As we grapple with their history, it is crucial that the truth is told about their complex lives and place in the long, torturous search for American freedom.

Realistically, monuments change and evolve along with politics. An ancient temple to a city’s patron saint becomes the site for a cathedral, which later is transformed into a mosque by conquerors or morphs into a state-owned mausoleum for other famous people whose accomplishments a nation wants to recognize.

Most monuments actually are not set in stone, and many, like the Confederate ones, never depicted history but instead an ideology created to send an exclusionist message in the present and future. Many Confederate monuments were mass produced by a monument company experiencing a boom in business. The most interesting part about such statues is that when they are pulled down and broken up, they almost all are hollow inside. Despite their solid appearance, they crumple like the defunct ideologies they represent.

History itself is different, made up of people from a wide variety of backgrounds who come together in a particular moment in time. History belongs to all of them and to none exclusively, as does the future. It behooves cities and towns to create and adorn public spaces in such a way that they uphold that diverse reality. Should they miss this opportunity, they are doomed to repeat the scenes of violence and unrest that we have witnessed repeatedly. Neither history nor the future are kind to those who resist people’s right to coexist alongside each other.

Some governments have quietly warehoused toppled statues. Some have moved them to museums or centers for historical study where they can reside safely because they are stripped of their public and quasi-official role. In best case scenarios, they are interpreted accurately. In the worst, they continue to perpetuate versions of the Lost Cause myth. Sometimes public spaces that they have vacated are devoted to celebrating the history of civil rights struggles, a topic long overdue for recognition in some communities.

Placing relics of a racist past in museums places an enormous burden on those institutions to interpret them accurately. Many Civil War reenactor/museum guides are militant about historical accuracy as far as their gear and knowledge of battles, but much more needs to be done to place the Confederacy accurately in the context of the history of white supremacy and racism.

Some communities have committed to reinterpreting the past as completely and honestly as possible. They recognize that people of all races have a strong attachment to their history and it needs to be told cooperatively to arrive at the truth about a location’s history and landscape. In the best scenarios, universities, towns, states, museums, historical sites and public places join in the effort to showcase people of all colors and classes that participated in their histories. A huge body of research on slavery, the Civil War and the civil rights struggle exists to support this effort. What is needed is the public will to do so with monuments, museums, significant historical sites and landmarks.

Some historians, although they find the Confederacy reprehensible, are alarmed by the idea of destroying historical relics because they believe such destruction smacks of extremism. Others agree with the removal of blatantly Confederate statues that were erected only to commemorate the Confederacy, but draw the line at taking down statues of Thomas Jefferson or other slave holders who also helped build the foundations of American democracy.

They have a point, but there is still a lot to be said for getting rid of blatant ideological eyesores and moving on. Robert E. Lee opposed erecting Civil War statues at the Gettysburg battlefield, saying, “I think it wiser not to keep open the sores of war, but to follow the examples of those nations who endeavoured to obliterate the marks of civil strife and to commit to oblivion the feelings it has engendered."

I experienced the negative emotional reaction many people feel upon passing Confederate statues when I often had to pass the Confederate monuments in Raleigh, North Carolina, while getting a master’s degree at North Carolina State University. At the same time, I was doing Civil War research that revealed the huge disconnect between slavery and the war and the benign impression given by the monuments.

The removal of the monuments is a flashpoint in the country’s culture wars, with polls in recent years showing Democrats as more supportive of removing monuments and Republicans more reluctant to do so. Abraham Lincoln’s Republican Party as well as the Democratic Party of that era would have been amazed.

It remains to be seen what will happen with historical sites associated with figures such as Jefferson Davis, some of which have gift shops filled with Confederate memorabilia and which are popular spots for re-enactments by people dressed as Confederates.

Studies have indicated that American taxpayers have spent $40 million in the past decade on Confederate-related monuments, statues, homes, parks, museums, libraries and cemeteries. This public funding of Confederate-related symbols has become troubling because of violence by white supremacists. Before Dylann Roof killed nine African Americans at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, he had spent a day touring places associated with slavery such as a Confederate museum and former plantations. He’s not alone – some white supremacists see these sites as sacred representations of what the country should be and would have been had the Confederacy won the war.

Some of these sites claim they are neutral historical institutions, but have halls filled with Confederate battle flags, uniforms and weapons and some play down slavery in their presentations. Some even claim that slavery was of benefit to enslaved people.

Lest we think that such views have long ago joined the ash heap of Civil War history, I recall a few years ago when my children were astounded when students in their North Carolina high school made such statements during a racially integrated history class. The teacher made no effort to correct them. Hopefully, we are getting closer to the day when that changes.

Related photos:

Check out these related items

The History of Race in America

The racial history of the United States belongs to us all, with the responsibility to resolve the accompanying outstanding problems.

Getting A Vaccine against Racism

A mother of non-white children compares her fears for her children because of COVID-19 and her fears for them because of racism.

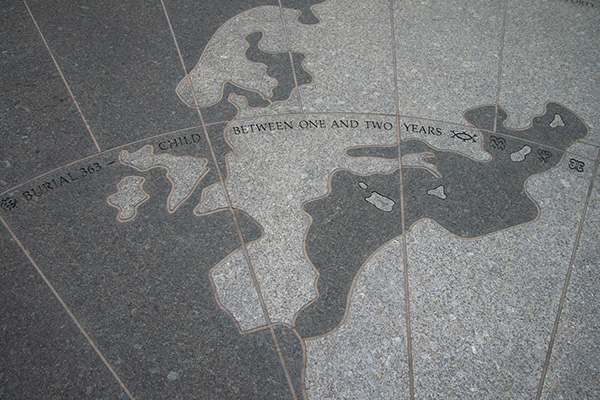

Memorial to Once-Forgotten People

A moving monument and burial ground in Manhattan comemorates enslaved people who once made up more than a third of New York City.

Wolf in Ship’s Clothing

The picturesque town of Bristol, Rhode Island, once was a slave port and home of the nation's leading slave traders, the DeWolfs.

What does it mean to be Hispanic?

What does it mean to be Latino or Hispanic in the United States? This blog explores the ambiguous origins of these two terms.