Memorial to Once-Forgotten People

Photos by Forrest Anderson

As the Museum of African American History moves toward its 2020 opening at the infamous slave ship docking site, Gadsden Wharf in Charleston, South Carolina, it's worth taking a quiet moment to reflect on the place far to the north where the first enslaved African Americans lived, worked and died.

The enslavement of Africans in the United States began in New York City when the Dutch West Indies Company imported 11 African slaves in 1626. The first slave auction in the North American colonies was held in the city as well.

When most people think of New York City’s history, they imagine a world of largely European immigrants disembarking from ships, going through immigration and eventually settling down in the boroughs or ethnic neighborhoods. However, that iconic historical period that came to define the city’s culture was preceded by a wave of enslaved Africans brought into New York against their will.

Today, they are commemorated at the African Burial Ground, a national monument at the Ted Weiss Federal Building at 290 Broadway in Manhattan. The story behind the monument spans almost 400 years of history encompassing slavery and civil rights.

The monument includes burial mounds of enslaved African Americans from the 17th and 18th centuries.

The Dutch West Indies Company acquired those first enslaved African men, who were from Angola, the Congo, Guinea and perhaps other locations, from the Portuguese. They were being transported on a Spanish ship to the West Indies when the Dutch Indies Company took them as prizes. In New York, the company forced them to work as field hands. Two years later, three enslaved women from Angola were transported to New York. Women slaves became domestic servants in the homes of company officers. Other African slaves were imported from the sugar colonies of the Caribbean. Under the Dutch, slaves could intermarry with working-class whites.

The slaves were allowed to earn wages in their free time and own moveable prooerty but not land. They could raise their own crops on the company's land. The Dutch allowed some to gain their freedom, own land and have small farms in the area around Washington Square Park. A slave could sue another person and their testimony could convict free whites. However, children of enslaved women were considered born into slavery regardless of the father's ethnicity or status.

Slavery in New York was an outgrowth of the Dutch slave trade in the Caribbean, Southeast Asia and Africa. The Dutch West Indies Company at first dominated the import of slaves from the West and Central African coasts. The slaves were used to clear forests, build roads and do other labor for the Dutch colony. Many became skilled artisans and builders or worked at the docks.

In 1664, when the British took over the city, its population was 40 percent slaves, and by 1703, slaves were working in 40 percent of the households in New York City. This percentage was far greater than in other cities in the northeast. A quarter of the city’s population were enslaved at the time of the American Revolution and New York had the second-largest number of slaves in the American colonies after the famous slave port of Charleston, South Carolina. Slaves were sold at auctions on Pearl Street, Wall Street and the East River.

The British treated slaves more harshly than the Dutch, allowing them to be whipped and banning them from burial in the city’s Trinity Church yard. Instead, they were buried in an African burying ground in an area outside the city near Chambers Street. Slaves revolted in 1741, but the revolt was quashed. At least 13 slaves were burned at the stake and 18 hanged.

The British changed their tune during the Revolutionary War when they occupied New York City. In an effort to damage the American economy, the British offered freedom to slaves who left their pro-revolution masters. Thousands of slaves fled to the city, and the British gave them financial incentives to join the British military. In the 1780s, 10,000 African Americans lived in New York, which came to be seen as a haven for African Americans. After the war, the British transported 3,000 freed African Americans to Nova Scotia, other British colonies and Britain. Others fled the city to evade slave traders hired by former masters to recapture them.

Many freed African Americans stayed in the city, however, and represented a third of the city’s African American population. In 1788, there was a riot over revelations that doctors and medical students were digging up some of the bodies in the African American cemetery to dissect them. The cemetery closed in 1794 and was filled in with landfill for development.

In 1799, New York City passed a law that allowed children born to slave mothers after July 4 that year to be legally free after serving as indentured servants until age 28 for men and 25 for women. However, those born before that were considered slaves for life. This continued until New York abolished slavery on July 4, 1827 and freed more than 10,000 slaves. They were not allowed to vote until 1870, however

In 1846, while America’s first department store was being built at 280 Broadway and Chambers streets, several skeletons were unearthed and a homeowner digging a cellar for his house found human bones in the early 19th century. He thought the site was a potter’s field. Later, a large number of human bones were found during the excavation of the R.G. Dun and Company building (later Dun & Bradstreet). There was speculation that they were the remains of African Americans who were executed after the 1741 revolt.

Waves of European immigrants overwhelmed this population during the 19th century. Migration north by African Americans from the South in the 20th century dwarfed the numbers of descendants of early New York slaves, and the vast majority of African Americans who live in the city today are not their descendants.

The early African American history of the city was largely forgotten until the remains of more than 410 Africans who were buried on a 5-6 acre site in lower Manhattan in the 17th and 18th centuries were found during escavations for the Ted Weiss Federal Building. The discovery of intact burials was announced in October 1991. Studies indicated that more than 15,000 people were buried there, most of whose names are unknown. The cemetery was America’s largest colonial African American cemetery. Because of the large number of burials, the government realized that it would not be possible to excavate the entire burial ground. Activists protested the breaking up of some burials during the excavation, halting the construction for a 12-year archeological excavation and study of the site by a Howard University team. In the process, the site and federal building were redesigned to make room for a memorial to those who were buried there.

The remains at the site were buried in wooden boxes. Allmost half were children under 12 years old. The site contained the largest and earliest group of remains for an immigrant group in America. Some of the graves included items related to African customs and burial practices and some corpses had filed teeth, which was an African custom. The remains were studied and then buried under mounds at the site in a commemorative ceremony.

A 25-foot monument of granite from South Africa and North America was completed at the site in 2007. Its shape symbolizes the ships that carried thousands of enslaved Africans to the Americas.

The monument is symbolic of the ships that carried enslaved Africans to the Americas.

The ark has a passageway called The Door of No Return which symbolizes the capture and slavery of Africans who never saw their homes again. The triangular passageway represents the Triangle Trade in which slaves were tranported from West Africa to the Americas and traded for raw materials that were transported to Europe. These materials were made into manufactured goods that were in turn taken to Africa and exchanged for slaves.

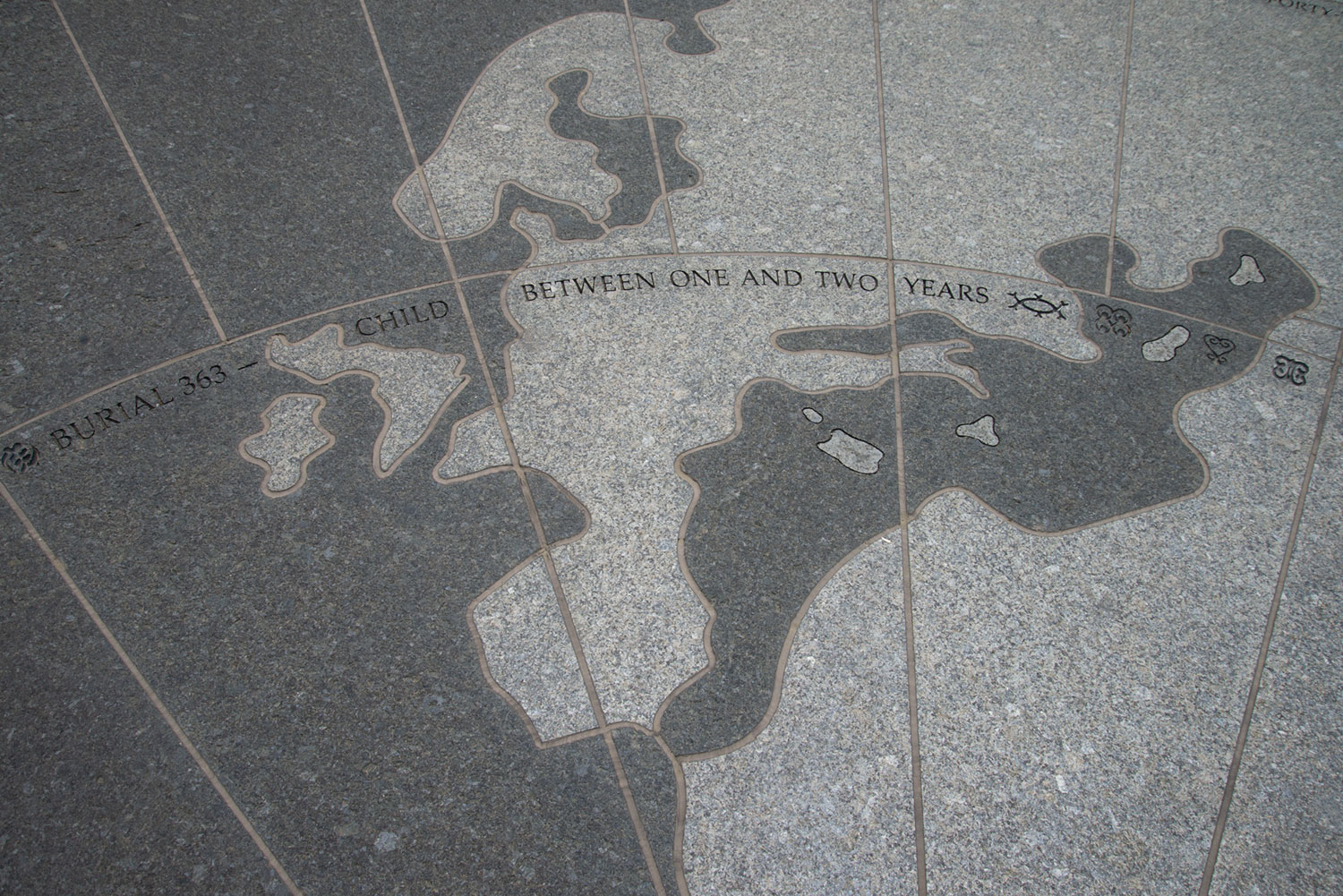

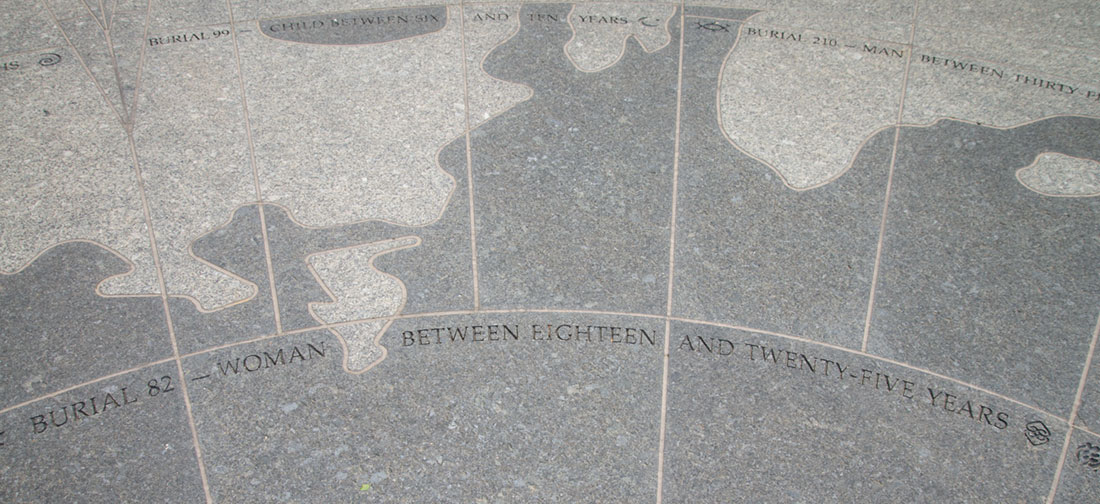

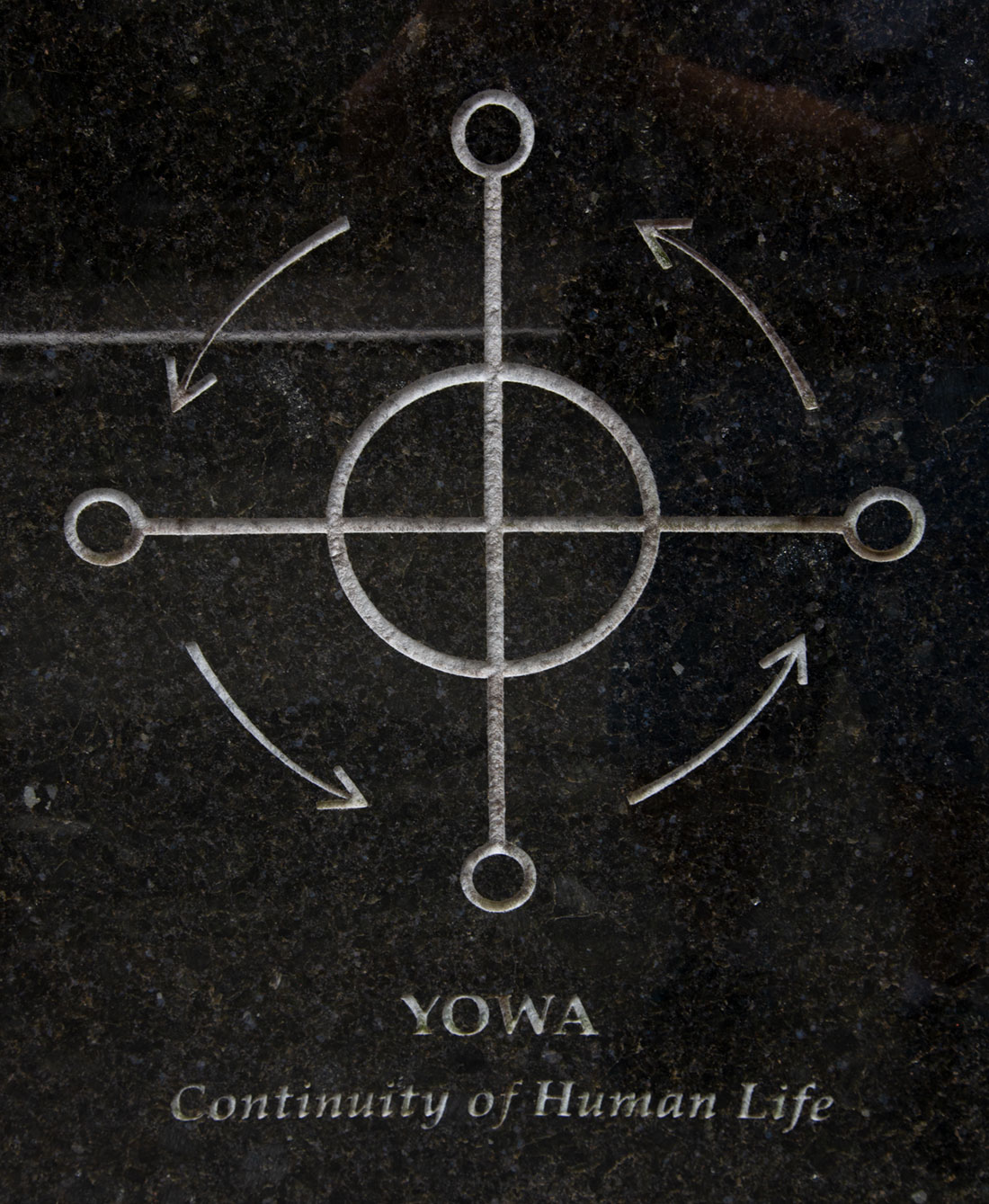

From the passageway, the visitor descends a flight of stairs that are a symbolic bridge between the living and spiritual realms to a stone map called The Circle of Diaspora. Around its face are carved basic information about individual bodies found in the burial ground and symbols from Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean and other areas in the African Diaspora.

A carving about one of the persons who was buried on the site.

A symbol on the monument.

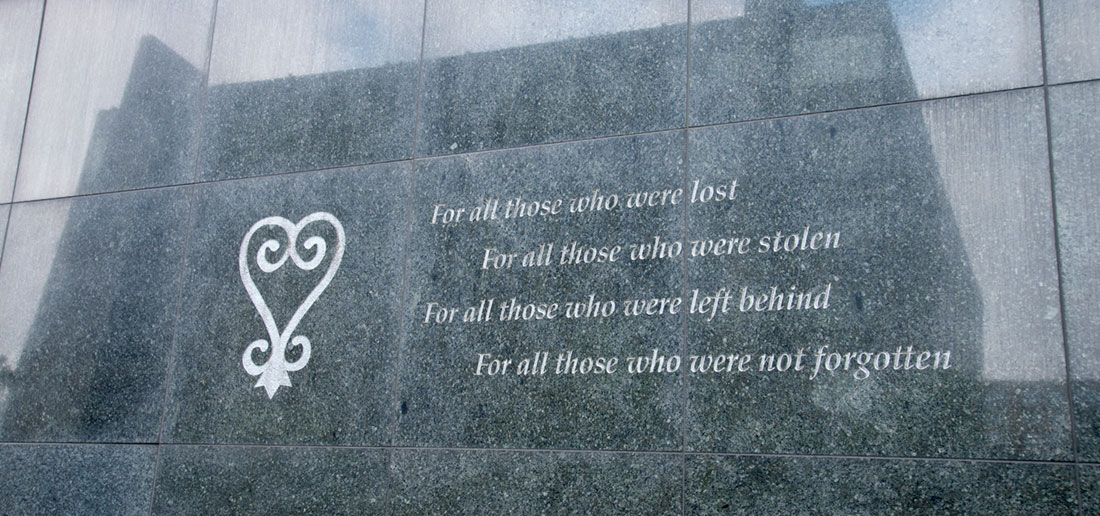

The quiet monument with its burial mounds in which the excavated bodies were reenterred is a moving place for quiet contemplation and prayer.

The commemorative inscription on the monument.

The discovery of the site, one of the most significant African American historical sites in the United States, changed the field of early African American history and has resulted in new books and studies on the topic.

Check out these related items

The History of Race in America

The racial history of the United States belongs to us all, with the responsibility to resolve the accompanying outstanding problems.

Getting A Vaccine against Racism

A mother of non-white children compares her fears for her children because of COVID-19 and her fears for them because of racism.

The Racism of Confederate Statues

The racist past associated with the Confederacy and Confederate monuments has a complex history.

Wolf in Ship’s Clothing

The picturesque town of Bristol, Rhode Island, once was a slave port and home of the nation's leading slave traders, the DeWolfs.

The Land of Junipero Serra

Junipero Serra's "sainthood" is controversial, but the extent of his cultural impact on California is indisputable.