Getting A Vaccine against Racism

Photos by Forrest Anderson

Will it ever end?

My stomach clenched in a familiar knot as I watched the video of George Floyd being held down with a policeman’s knee in his neck, pleading for “Mama.”

Over the past several months, an invisible pernicious virus has spread over the United States leaving an unimaginable death toll in its wake and a fear that has permeated every city and town. Going to the grocery store, getting gas, working in a public place have become infused with constant wariness, anxiety and a sense of relief upon driving away.

Why is it that that the knot in the stomach caused by the threat of the coronavirus feels just like the knot in the stomach that mothers of non-white children feel every time their children get on a school bus or when their adult children leave for work in the morning?

When will this constant worry that their children are in danger from racism ever go away? How long will it take and what will it take for us to develop an anti-racism vaccine?

I first developed that knot in my stomach in elementary school, growing up with black hair and olive skin bequeathed me by ancestors whose DNA comes from the Mediterranean region. At my mostly white school, I learned to negotiate racism by being a quiet student who got good grades and didn’t make waves. I made friends in the Spanish Club and went on to minor in Latin American Studies in college before becoming an international journalist. Along the way, I learned to deal with people who looked quizzically at me and asked “What are you?”

I never got rid of that pit in my stomach, though.

Working abroad, I discovered how fluid race is. In the United States, I was most often asked if I was Hispanic, but in China, I often was assumed to be part Chinese or from Central Asia. Middle Easterners have asked if I’m from the Middle East and Indians if I’m part Indian. In the Mediterranean region, I’m assumed to be local in a way that makes me feel at home. Being able to blend in in many lands has been a blessing that has helped me make friends and learn about many different cultures. As I have moved between cultures, I have realized that race does make a difference to many people in many cultures, but not in the way that many think it does. Our American categorizations of what race is, even the ones on the federal forms, are largely myths based on many oversimplified assumptions.

Racism is fundamentally a set of such learned assumptions. People make assumptions about other people based on their own cultural training. They assume people are a certain race or ethnic group and attach to that group a plethora of characteristics that those people may or may not possess. Some of these assumptions are fairly harmless stereotypes on an average day, but they still exist in the general environment like a lurking virus waiting for an opportunity to cause a violent outbreak.

Therein lies the fear that resides in the mothers of non-white children, waiting to flare up like an untreated ulcer in any crisis. It flares up when a child comes home in tears day after day because she is constantly called a racial slur by a bully while the teacher chooses to ignore the problem. It flares up when a young adult son is told he is not allowed to date some bigot’s daughter because of his race. The knot in the stomach always feels the same.

Over centuries, we’ve all learned to live with this pernicious disease and its toll in the same way that we now are learning to live with the pandemic. Our ability to adapt doesn’t make either one any less of a threat.

George Floyd’s death and the protests that have followed it came for me on the heels of fears about the safety of my Asian American children after news reports surfaced of Asian Americans being attacked or being the target of racial slurs because the coronavirus originated in China. That fear in turn followed worries about the potential of anti-immigration sentiment against Mexican Americans - which is personal for me because some of my family members are Mexican American. If it’s not one ethnic group it’s another with racism. It jumps from one target to another depending on the catalyst.

This exhausting mother’s fear of racism comes on top of all the other fears that mothers everywhere are facing as they worry about their children’s safety amid the coronavirus pandemic. I also worry about my daughter’s safety as she has worked throughout the pandemic at a vet clinic, sanitizing sick animals so that their fur can’t transmit the virus to the clinic staff. I worry about my social worker son, wearing a mask as he works at a non-profit that trains unemployed people for jobs.

My Asian American children are college graduates who paid their own way through school. All are skilled workers with diverse interests and talents who make valuable contributions to American society every day. They are loving children who recently pooled their money together to replace my sewing machine when I broke it in the middle of making masks for front-line workers. They are complex, competent human beings. No one deserves to be reduced to the simplistic level of a racial slur or to be treated as less than the valuable and complex human being they are.

George Floyd was the son of a woman whom he called “Mama” in the last moments of his life. He was a human being whose family remembers him as always having a smile on his face. He was a star football player in high school who was nicknamed the “gentle giant” because of his height. He had received a basketball scholarship. He was the father of three children. He had just lost his job in the middle of a national crisis. He had texted his uncle to wish him a Happy Birthday just a few days earlier. If he broke the law, there are legal and police procedures to protect both the rights of the store owners who called the police about his behavior and his rights. They should never include inhumane behavior or assumptions.

Unlike the coronavirus, we have a vaccine against racism. All we have to do is use it. It’s as simple as adjusting our assumptions - assuming that everyone we meet is human, with human rights that we as Americans and fellow human beings need to uphold and respect. Out of this core assumption should come all of our laws, pay scales and public and private behavior. While we’re all working toward a new normal, this is the obvious place to start.

Check out these related items

The History of Race in America

The racial history of the United States belongs to us all, with the responsibility to resolve the accompanying outstanding problems.

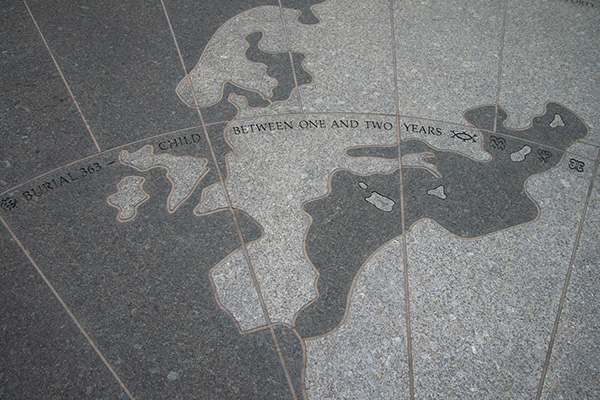

Memorial to Once-Forgotten People

A moving monument and burial ground in Manhattan comemorates enslaved people who once made up more than a third of New York City.