Wolf in Ship’s Clothing

Photos by Forrest Anderson

Scattered on the American landscape are isolated traces of the heinous American history of slavery – slave cabins at a plantation that is now a historical site, shackles at a museum, a monument at a slave cemetery. We wince when we come across them and quickly move on, with little understanding of how pervasive slavery once was to not only the American economy, but the economy of the Atlantic Ocean.

As the 200th anniversary of the U.S. law that made slave trading a capital offense approaches in 2020, the Atlantic slave trade once again is emerging as a topic of interest. Surprisingly, the former slave state that comes to the fore in this discussion is tiny Rhode Island on the New England coast.

The most prominent landmark in the town of Bristol, Rhode Island, a picturesque deep-water seaport named after Bristol, England, is Lindon Place, a columned white mansion filled with antique china, rugs, carved furniture and other items connected with its former owners, the most prominent slave trading family in the United States.

Bristol Harbor, Rhode Island, where slave ships one docked in the 18th and early 19th centuries. The small dark stone building to the right of the yellow building is a warehouse built of African timbers and stones brought to Bristol as ballast on slave ships.

Bristol has a long storied history. Wampanoag Native Americans occupied the area and alternately befriended and went to war with the Pilgrims after they arrived in New England in 1620. Bristol was part of Plymouth Colony before being transferred to the Rhode Island Colony in 1747. The town was bombarded by the British Navy during the American Revolution after the townspeople refused to provide supplies for British ships. In retaliation, 30 buildings in Bristol were burned and some local people were taken prisoner.

The town, now a popular site for destination weddings and boating because of its historic architecture and fine harbor, has the longest continuous Independence Day celebration. Its history also includes a much darker story, that of the slave-trading DeWolf family.

Rhode Island’s beaches and excellent harbors meant that its economy developed on the water. The colony’s residents took to the sea, at first trading in small vessels along the coast, then engaging in commerce with neighboring colonies and moving on to privateering along the coast of Africa and Barbados. The first slave traders launched their ships from Newport, Rhode Island, which became the economic center of the colony. Among sailors who joined this commerce were early members of the DeWolf family. Rhode Island farmers and craftsmen also began producing for the Atlantic trade. Atlantic commerce, especially the slave trade, brought Rhode Island merchants, tradesmen and farmers together.

African slaves were brought into Rhode Island by 1652 and slavery was promptly outlawed. But the pull of the Atlantic slave trade eroded those laws, and a century later, Newport and Bristol were the major slave markets in the American colonies.

Rhode Island slave traders played a key role in the international slave trade and in associated businesses that maintained the slavery system in the West Indies and the American South. Rhode Islanders financed Atlantic slave trading voyages and traded slaves, rum, food, lumber, pork, butter, cheese, onions, cider, candles and horses, tools and clothing to sugar, rice and cotton plantations in the West Indies and American South, which needed those goods because they were largely one-crop operations. In payment for slaves, the traders received sugar, molasses, cotton, ginger, indigo, linen, woolen clothes and Spanish iron in the West Indies, the American South and Latin America. The contribution of Rhode Island merchants, industrialists and farmers enabled slaveholders to make their plantations successful. Slavery permeated Rhode Island’s economy as much as that of any southern state.

Through the 18th century, Rhode Island traders controlled more than sixty percent of the North American trade in African slaves. The Atlantic trade involved an unprecedented movement of people and money. African traders and European traders in West Africa kidnapped and sold slaves to Rhode Islanders who transported 66 percent of them to sell in the West Indies, 31 percent to North America and three percent to South America in addition to supplying slave plantations with food and goods. In the first half of the 19th century, Rhode Islanders sent 131 ships to Africa, which transported more than 17,000 African slaves to the New World. The volume dwarfed slave trading by other colonies in both the north and south.

Although the trade was dangerous, with slave mutinies aboard some ships, it was highly profitable in this era as was the manufacture of rum in Rhode Island from molasses acquired in the West Indies. Rum was the drink of choice on the West African coast after 1713 and the currency used to buy African slaves. Rum distilled in Rhode Island from West Indian molasses was the number one export of Rhode Island. A slave woman cost an average of 190 gallons of rum and a man 220 gallons of rum.

Huge hogshead barrels like this one in Bristol were used to transport rum to Africa to trade for slaves.

After 1730, most professions in Rhode Island were directly tied to the slave trade. Sailors, sail makers, rope makers and painters worked on ships. Fishermen and farmers provided food for trade in the West Indies. Coopers made barrels to ship rum. Clerks, scribes and warehouse overseers conducted the business. Stevedores and team drivers loaded and unloaded ships. Merchants contributed tax revenue to the cities and served as bankers for the system. Of 120 Rhode Island ships in 1740, just ten were not employed in the slave trade.

African slaves accounted for 11.5 percent of Rhode Island’s population by 1755, and parts of the state had large-scale farming like Southern plantations. In some areas, a third of the population was slaves. Along with the large numbers of slaves came whippings, runaways and harsh laws to control the slave population. Slaves were sold at auction houses in Newport. By the mid-18th century, enslavement was part of everyday life in Rhode Island. Merchants and tradesmen used slave labor to expand their businesses.

The Atlantic plantation system grew over hundreds of years. Plantations emerged in the Mediterranean in the 11th century, were established on West African islands in the 14th and 15th centuries, were introduced to South America and the Caribbean in the 16th century and were in North America in the 17th-19th centuries. They had mostly enslaved labor forces of usually of 50 or more, with managers and supervisors who controlled them. The plantations produced crops such as sugar, rice or tobacco for a distant market. The plantations usually were financed by merchants far away. Rhode Islanders created a niche in this system as suppliers and importers, becoming dependent on the system.

From 1650 to 1850, an estimated ten to fifteen million Africans were transported to the New World. The British North American colonies received less than 5 percent of the slaves transported, with most of them going to the West Indies and South America. Profits from the Rhode Island slave trade were invested in mills, distilleries and factories as well as banks, so people borrowed money from slave traders.

Slave traders weren’t the only ones to become wealthy. Farmers who supplied goods for the system prospered and modeled themselves after British gentry. They built manor homes, took European vacations, commissioned portraits, married other wealthy participants to further their business interests, and hired private tutors for their children. They rarely performed manual labor. They commonly whipped slaves and threatened to sell them. Chronic runaways were maimed and slave records commonly identified slaves by scars from whipping or similar injuries.

A wolf carved on an antique chair at Lindon Place, a symbol of the DeWolf family.

Rhode Island became one of the states that created the racial category “black” to describe non-whites, applying it not just to those of African descent but to Native Americans in an attempt to strip them of their claims to their lands. Merchants and slave traders became town councilmen, state legislators and governors. They wrote white superiority and black inferiority into local law.

Between 1709 and 1807, Rhode Island merchants bankrolled at least 934 slaving voyages to Africa's coast and transported an estimated 106,544 slaves to the Americas.

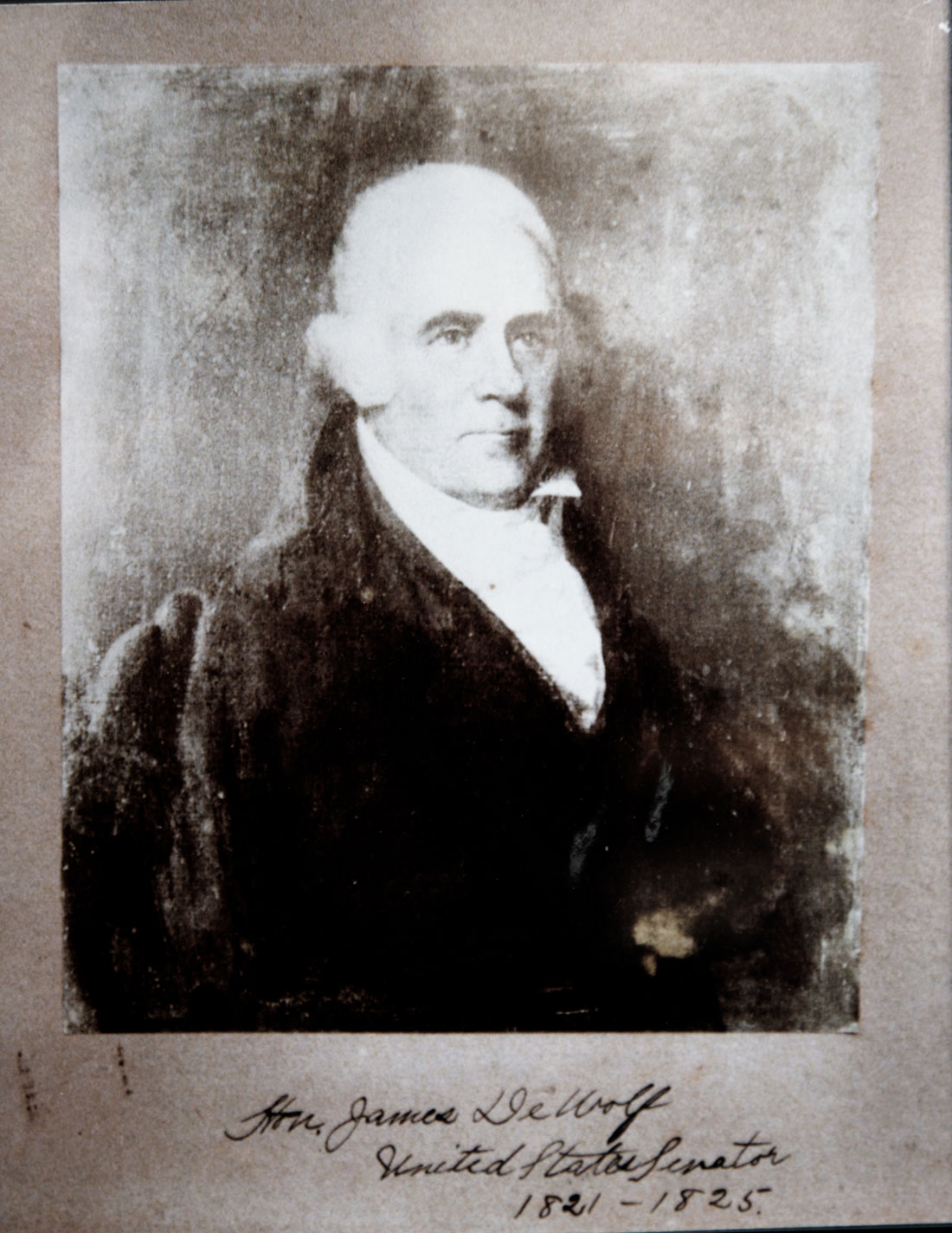

Mark Anthony DeWolf and his employer Simeon Potter began to trade in slaves in 1769. Mark Anthony’s son, James deWolf, born in 1764, went to sea as a sailor on a private armed vessel during the late years of the American Revolution. He participated in several naval encounters with the British and was captured twice by them. After the war, he became a ship captain. He purchased seasoned slaves in Cuba and other West Indies ports and transported them primarily to the American South. Although Rhode Island outlawed slave trading by 1787, James and his family continued to finance and command slaving voyages to West Africa long after that.

In 1789, James commanded a voyage of the sailing ship Polly from Bristol to slave trading posts on the west coast of Africa. There he bought 142 enslaved men and women, and sailed for the West Indies. About two weeks into the journey, a middle-aged enslaved African woman whose name is unknown contracted smallpox. This was a crisis. The patient was quarantined and as her illness worsened, she was “put in the main top” for two days to prevent the disease from spreading to the crew and slaves.

In an emergency meeting, two crewmen who had already had smallpox and were thought to be immune reported that they had examined her and thought she couldn’t survive. Other crew members agreed. The ship was 50-60 days from its next port. Those at the meeting concluded that the only option was to throw the sick woman overboard, but decided to wait until the next morning in hopes she would be dead by then. DeWolf apparently asked for a volunteer to throw the sick woman overboard, but the crew all refused.

The next morning, DeWolf went up to the main top with a crew member to find the woman still alive. DeWolf blindfolded and gagged her so the other slaves couldn’t hear her screams. Four sailors lowered her to the deck. DeWolf asked a sailor to help him with a grappling hook, which they attached to her chair. The two men lowered her into the ocean. She sank immediately and drowned.

In 1791, an unknown person in Rhode Island accused DeWolf of murder in the case, and a grand jury indicted him. DeWolf promptly sailed away to the Caribbean island of St. Eustatius, where he continued his slave trading business by correspondence with his brother. He apparently was charged with murder in St. Eustatius, but the judge decided not to prosecute the case. DeWolf then moved to the Dutch colony of St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands, where he was charged with murder in the case in 1795 after being accused by a fellow ship captain, Isaac Manchester. Two members of the Polly’s crew, one of whom had participated in the murder as he earlier had survived smallpox, said the slave had to be thrown off the ship to save the other slaves and crew and it was uncertain whether she was alive when lowered into the water. This was justifiable under maritime law of the time. DeWolf testified and the judge ruled in his favor, declaring that “this act of James De Wolfe was morally evil, but at the same time physically good and beneficial to a number of beings.” The judge found that it was the captain’s “duty” to prevent the infection from spreading further aboard ship and that deWolf had chosen “out of two evils the least.” He determined that DeWolf “did not act in this case merely by his own will, but after a mature deliberation with his officers and crew who found it to be the only means to save them all from misery and destruction.”

The judge found DeWolf not guilty, and the charge “groundless.” He didn’t seem to consider that DeWolf was responsible for the entire situation which had resulted in the woman’s death because he was transporting her and her fellow slaves across the ocean against their will. A crew member testified that DeWolf said he regretted the loss of such a good chair.

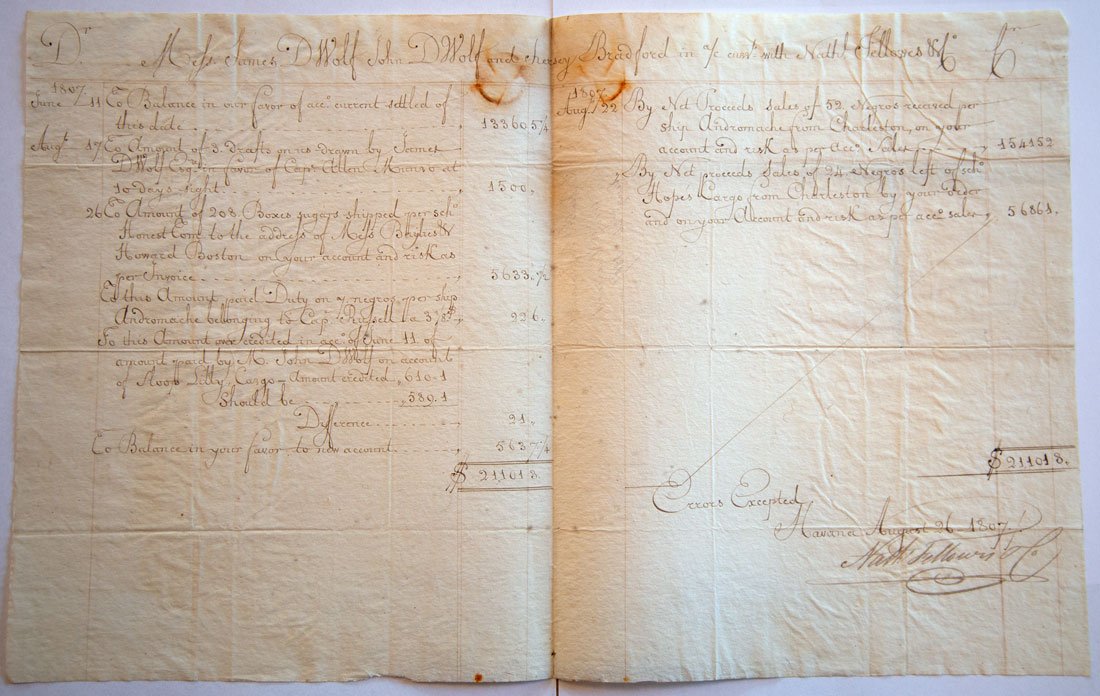

Meanwhile back in Bristol, DeWolf’s family eventually persuaded the federal marshal in Rhode Island to drop the arrest warrant there. James returned to Rhode Island on the Polly. He recorded that he sold 109 slaves at a profit, and kept 10 for himself. His actions were a violation of a 1787act banning slave trade in the state. DeWolf with his family financed 25 more slaving voyages. The DeWolf family is believed to have transported more than 11,000 slaves to the United States before the United States banned the African slave trade in 1808. The DeWolfs built their fortune on shipping enslaved Africans from Africa to auctions in Charleston, South Carolina, and other southern ports; Havana, Cuba and other Caribbean ports; their three sugar and coffee plantations in Cuba and their own homes.

The DeWolfs and others involved in the businesses of slavery were far from social pariahs – they dominated the state’s social and political elite and helped shape laws and government appointments that enabled them to carry on the trade. Samuel Cranston, a slave trader and captain, served as Rhode Island’s governor from 1696 to 1725. William and John Wanton, who served as governors, were prosperous slave trading Quakers.

James DeWolf married Nancy Ann Bradford, the daughter of Rhode Island Deputy Governor William Bradford, who was the great great grandson of William Bradford of the Mayflower. James, while trafficking in humans, served as a state legislator for 25 years and then as a U.S. senator. He became the second-richest person in the United States by trading slaves and investing in sugar and cotton plantations in Cuba.

Slave trader James DeWolf.

For more than half a century, Rhode Island slave trader families such as the DeWolfs were among the great mercantile families of America. They reaped huge profits from the slave trade that have cascaded down through history in the privileged lives of many of their descendants and the uses to which their money was put. For example, the slave-trading Brown family donated so generously to Rhode Island College that its name was changed to Brown University. The university continues today to grapple with the controversary surrounding its slavery past.

During the War of 1812, James fitted out privateers under the authority of the U.S. president, and one of his ships, the Yankee, was the most successful privateer of the war. It captured 40 British vessels worth more than $5 million during the war.

James owned a mill and a rum distillery to provide rum used as an exchange good in West Africa. The distillery converted 300 gallons of molasses to 250 gallons of rum per day at the cost of about ten cents a gallon. The deWolfs took rum to West Africa and traded it for slaves. Then they traded slaves bought in Africa for molasses from sugar plantations that was a key ingredient for rum making. James built a warehouse on Thames Street in Bristol made of heavy timbers and large stone blocks he had imported from Africa as ballast on his ships. He unloaded and loaded his slave ships there.

Above, James DeWolf's warehouse in Bristol and, below, the area where slaves once disembarked from slave ships at the warehouse.

He also started with his brothers and nephews the Bank of Bristol and an insurance company that financed and insured their slave ships. From 1805-1807, their Mount Hope Insurance Company insured 50 slaving voyages. The main destination for many of their slave ships was Charleston, South Carolina, where they had a slave auction house.

This 1807 document of James DeWolf's, now in the Bristol Historic & Preservation Society, lists accounts involving the sale of 83 slaves.

The conventional wisdom that the American Revolution postponed the question of slavery until the Civil War is untrue in the North. Slavery began to break down in the North during the chaos of the revolution while it became more entrenched in the South, setting the country up for the eventual Civil War. Quaker abolitionists and powerful slave traders clashed over slavery in Rhode Island. The abolitionists prevailed because the slavery system broke down during the war, first as a black regiment from Rhode Island was created and fought in the war for five years and its members were given freedom in exchange for their service, and then as many slaves ran away during the war.

As the abolition movement grew under the leadership of the Quakers, who had come to believe that slavery violated their beliefs in the equality of all men and manumitted their slaves, slave traders fought abolition, violated state and federal laws prohibiting the slave trade and sought federal aid. A 1794 federal law forbidding Americans from carrying slaves between foreign countries or into states with statutes against the trade and a 1797 law forbidding Rhode Islanders from participating in the Atlantic slave trade were blatantly disregarded. Rhode Island traders after 1787 transported more than 40,000 African slaves to the Caribbean and southern United States, more than six times that of other New England merchants combined.

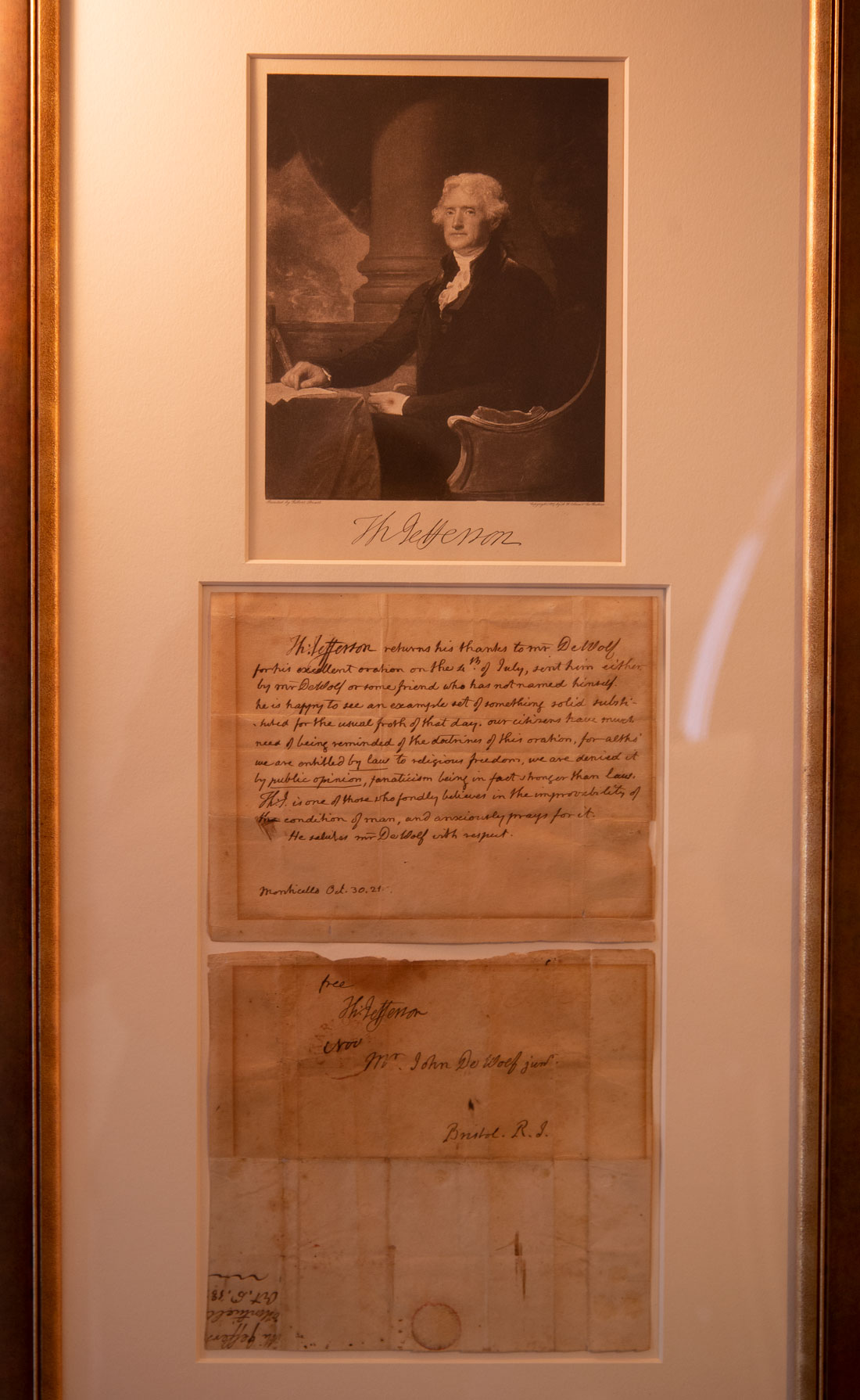

In 1784, Rhode Island passed a gradual emancipation law in which children of slaves born after March 1 were to become free when they were grown. In 1808, the international slave trade in the United States was banned. After this, the DeWolfs talked U.S. President Thomas Jefferson into splitting the federal customs districts in Newport, Rhode Island, to permit the appointment of a customs inspector just for Bristol. This was Charles Collins, James DeWolf’s brother-in-law, who ignored the slave ships that went in and out of Bristol’s harbor. Collins was part owner in one of the DeWolfs’ Cuban plantations. The DeWolfs had made major contributions to Jefferson’s presidential campaign, and he took no action on protests about Collins’ appointment.

A letter from Thomas Jefferson at Monticello complementing James DeWolf on an oration he gave.

Three U.S. presidents – James Monroe, Andrew Jackson, and Ulysses S. Grant – visited Lindon Place.

The DeWolfs typically kept slaves at their Cuban plantations when prices were low and then sold them elsewhere when prices went up.

James DeWolf got out of the slave trade in 1808, but his nephew George bought three of his ships and continued in the trade until 1820, when slave trading was made a capital offense. George and other slave traders continued in the trade by selling their ships to a Cuban slave trader for a dollar. It would sail around the Atlantic slave triangle under the Cuban flag. The DeWolfs would then buy it back. It is estimated that on one voyage of the DeWolf slave ship MacDonough, DeWolf’s captain purchased 400 slaves for $16 each, sold them in Havana for $500 each and cleared over $100,000. George invested this money into a plantation in Cuba called Noah's Ark. George worked closely with Charles Collins, who when he left his position as revenue collector in Bristol in 1820 burned all of his records so there is no trace of his illegal activities in connection with George.

Slave trader George DeWolf.

George built the Federal-style white Lindon Place in 1810, one of the best examples of Federal architecture in New England. It has Palladian windows, Corinthian columns flanking the front entrance and a magnificent three-story spiral staircase. It sits on 1.8 acres in sculpture gardens with Greek bronzes and an 18th century gazebo.

Above, the spiral staircase at Lindon Place and below, the gardens there.

The DeWolfs built the economy of Bristol and many of the buildings they built are still there today. The family later included state lawmakers, philanthropists, writers, scholars, actors and actresses and Episcopal bishops and priests. They intermarried with other prominent families.

When the slave trade became less profitable, George sold guns to revolutionaries in Central and South America at high prices. By getting new Latin American governments to issue privateering licenses to his ships, he preyed on commerce in the Caribbean. Often DeWolf played one side against the other. Many of his critics believe his vessels were engaged in piracy.

Because George spent lavishly, he became heavily indebted to his backers. He borrowed heavily from friends, neighbors and acquaintances, even his slaves. In 1825, George’s sugar harvest on his plantation in Cuba failed. His finances collapsed as banks and creditors demanded repayment. At the same time, his infant daughter, Julia, died. On December 6, 1825, Julia was buried. That night in a snow storm, George, his wife, their six children and all the valuable goods they could put into their wagons and coaches slipped out of Bristol. They arrived in Boston and, after declaring bankruptcy, boarded a small vessel and went to Cuba. The entire population of Bristol, including George’s relatives, were furious. Townspeople stormed into his mansion, ripped the damask curtains off the walls and the chandeliers down and hauled valuables from the mansion all night long through the snow. By dawn, the building was empty. George retired to his plantation, Noah's Ark. In 1844, he returned incognito and stayed in Bristol for a while. He died in Dedham, Massachusetts with little wealth.

Meanwhile, back in Bristol, George’s cousin added an octagonal sun room to the mansion in 1837, then two wings – a ballroom and a kitchen. The house changed hands until it was purchased for George’s daughter, Theodora Colt, who restored the mansion in the 1860s-70s and named it Linden Place. The Great Gatsby starring Mia Farrow and Robert Redford was filmed at Linden Place in 1974. The building was restored in the 1990s as a historic house museum.

The sun room at Lindon Place.

The DeWolf family continued after 1820 to maintain slave plantations in Cuba and be involved in textile production from slave-produced cotton. Over three generations and half a century, the DeWolf family were the United States’ most prominent slave-trading family. There are today half a million living descendants of people who were traded as slaves by the DeWolfs.

Internal trade replaced the African trade in the United States, uprooting hundreds of thousands of African slaves by moving them south and west and causing widespread misery by separating them from their family members. By 1810, some 97 percent of slaves in Rhode Island had been freed but it took decades more for slavery to die out completely because the law that freed the children of slaves also required freed people to provide years of compensated labor. In 1842, the state abolished all slavery.

Slavery became more severe in the South because the region was more dependent economically on actual slave labor while the North moved toward running businesses associated with slavery instead. Rhode Island still was so heavily invested in slavery that it continued to shore up the international slavery system. Rhode Island merchants played a major role in the development and maintenance of slave plantations in the American South and West Indies through businesses that supported slavery and the Atlantic slave trade that continued beyond American borders. Well into the 18th and 19th centuries, Rhode Island merchants continued to supply West Indies planters with slaves and goods in exchange for cash and molasses that was transported back to Rhode Island and processed into rum to sell in Africa and the West Indies for slave.

After the slave trade was outlawed in the United States, Rhode Island merchants invested their profits from the trade in textile mills that made the course wool clothing called “negro cloth” which Southern plantation owners used to clothe their slaves. James used wealth from the slave trade to form the Arkwright Manufacturing Company which built textile mills in Rhode Island in 1810. The textile mills were dependent on cotton cultivated by slaves in the south and shipped to the north. By 1860, 70 percent of all Rhode Island textile mills manufactured negro cloth. Rhode Island merchants also controlled much of the cotton business by providing credit to plantation owners who bought seed, farming equipment and slaves on credit. Rhode Island merchants maintained the close relationships they had had as slave traders with the South’s plantation owners, some of them maintaining offices in Charleston, South Carolina and continuing to ship goods into Charleston and other ports for plantations. Some married into Southern slaveholding families.

Northern industrialists bought and processed slave-picked cotton, while southern slave holders purchased northern manufactured cloth for themselves and their slaves. Rhode Islanders were among the leading producers of negro cloth in the United States. In the 18th century, Rhode Island traded slaves and in the 19th century, it clothed them. Abolitionists participated. The first textile mill in Rhode Island was opened by an abolitionist in 1789 who thought it was a good alternative to slave trading, although the textile mills used slave-grown cotton. The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 increased production fifty fold. Rhode Island merchants sold cloth to the same markets as those to which they had once sold slaves. They were familiar with the trade routes and had long established economic ties and personal connections to southern slaveholders. Many Rhode Island merchants spent considerable amounts of time in the South.

Southern planters and northern industrialists were called “the Lords of the Lash and the Lords of the Loom.” Profits from the slave trade and supplying slave societies with basic necessities helped fund the U.S. textile revolution. Slaves in the southern United States produced the bulk of the world’s cotton and almost all of the cotton consumed by the U.S. textile industry between 1815 and 1865. Northern manufacturers sold much of their manufactured cloth to southern planters. On the eve of the Civil War, countless northern businesses including insurance, railroad and shipping companies and banks were dependent on the slave-grown cotton trade.

Southern planters resented their dependence on northern manufacturing and the profits that northern textile manufactures made from negro cloth. This fed the eventual southern ideology of the Civil War, even while the relationship between northern and southern whites fell apart over expanding slavery into new western states.

The DeWolfs were featured in a 2008 documentary, Traces of the Trade: A Story from the Deep North, which was co-produced and directed by DeWolf descendant Katrina Browne. She invited other DeWolf descendants of the family to retrace the Triangle Trade route to confront their legacy. The documentary followed their journey. Her cousin, Thomas DeWolf, wrote a book about the trip, Inheriting the Trade: A Northern Family Confronts Its Legacy as the Largest Slave-Trading Dynasty in U.S. History.

Check out these related items

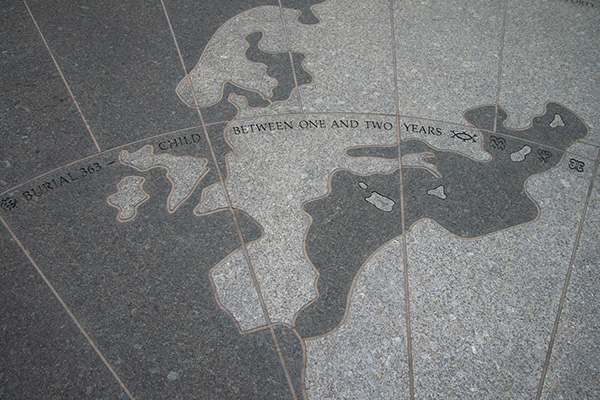

Memorial to Once-Forgotten People

A moving monument and burial ground in Manhattan comemorates enslaved people who once made up more than a third of New York City.

The History of Race in America

The racial history of the United States belongs to us all, with the responsibility to resolve the accompanying outstanding problems.

The Racism of Confederate Statues

The racist past associated with the Confederacy and Confederate monuments has a complex history.

New Orleans - Exuberant Hybrid

New Orleans's hybrid culture is the result of its 300 years as the gateway to trading networks of the Mississippi River.

The Land of Junipero Serra

Junipero Serra's "sainthood" is controversial, but the extent of his cultural impact on California is indisputable.