New Orleans - Exuberant Hybrid

Photos by Tai Anderson

New Orleans, Louisiana, is one of those vibrant, quintessentially American ports that sprang up and marched pell mell through its dramatic history without most of its contributors having any idea what the end result would be.

The city made it up as it went along, the result being an exuberant hybrid culture that is world-renowned for its music, fusion Creole cuisine and high-spirited celebrations and festivals. At the same time, the city’s tragic past of colonialism, slavery, the violence of the Civil War and Reconstruction, the long civil rights struggle, the devastation of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the on-going battle to keep the city from sinking lend somber tones to its colorful tapestry.

New Orleans, located on the Mississippi River upriver from the Gulf of Mexico, was founded as a trading port in 1718 by French colonists. It was named for Philippe II, Duke of Orleans (1674-1723), who was France's Regent at the time and whose title came from the French city of Orléans. New Orleans became a hub for Mississippi River trade. The rest of the globe shipped goods to New Orleans, which in turn exported goods from the interior of the North American continent.

A cruise ship on the Mississippi River near New Orleans. The city was the gateway to the Mississippi River trade.

French colonists imported enslaved Africans to provide labor on nearby plantations and in their homes, baptizing them into the Catholic faith and insisting that they marry in Catholic churches. As a result, the city became largely Catholic. The school system traces its origins to a convent and school founded by 14 French nuns sent by King Louis XV of France to New Orleans in 1727. The city developed a distinctive Creole society that blended French and African culture and included its own dialect and beliefs such as voodoo.

These photos show the interior of St. Louis Cathedral, the United States' oldest cathedral and the central landmark of New Orleans.

New Orleans was the territorial capital of a 828,000-square-mile swath called French Louisiana that cut through the middle of what later became the continental United States. The French controlled this vast area until 1762, when they ceded the territory to Spain and the city became Nueva Orleans. The local culture became a sophisticated, refined mix of French, Spanish and African influences that gave rise to the cuisine and lifestyle that pervades the city today.

During the American Revolutionary War, New Orleans was an important port for smuggling to the American rebels and transporting military supplies up the Mississippi River. After the revolution, Americans were interested in free transit on the Mississippi River to the sea so that they could move goods on the river. Spain in 1795 gave American merchants the right to use the New Orleans port for shipping agricultural goods and recognized American rights to navigate the Mississippi, which was vital to the growing trade of the western territories. However, Spain revoked the treaty allowing American use of New Orleans three years later. Spain restored the right in 1801, but then ceded the Louisiana territory back to France.

Napoleon regained ownership of the territory in 1800 with the idea that he was going to re-establish a French colonial empire in North America. Fear of a French invasion spread in the United States when Napoleon sent a military force to secure New Orleans in 1801. Then-U.S. President Thomas Jefferson was unhappy about Napoleon’s regime retaking control of New Orleans. Spain had a tenuous hold on the area, and it was likely that it could have passed ere long to the Americans, but he thought the French were less likely to do so. New Orleans was important because the produce of 3/8 of American territory passed through it to markets, Jefferson noted.

Napoleon’s plans were derailed by a successful anti-slavery and anti-colonial insurrection in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, now Haiti. The insurrection was the only slave uprising that led to the founding of a state free from slavery and ruled by non-whites and former captives. Its effects on slavery were felt throughout the Americas, including New Orleans, which was part of the Atlantic trading system and thus had ties to Saint-Domingue. Napoleon withdrew most French forces from Haiti to counter a threatened invasion of France by Prussia, Britain and Spain. With the loss of Saint-Domingue, whose sugar industry was an important economic contributor to France, Napoleon lost interest in the Americas. He decided to sell the Louisiana territory to the United States.

Pierre Samuel du Pont de Nemours, a French nobleman living in the United States, originated the idea of the much larger Louisiana Purchase as a way to defuse potential conflict between the United States and Napoleon over North America. Jefferson initially disliked the idea of purchasing Louisiana as it could imply that France had a right to be in Louisiana and he questioned whether a U.S. president had the constitutional authority to make such a deal. He also thought that to do so would erode states' rights by increasing federal executive power. However, he was prepared to go to war to prevent a strong French presence there.

Jefferson sent James Monroe and Robert Livingston to Paris in 1803 to negotiate a settlement, with instructions to head for London and negotiate an alliance with the British if the Paris talks failed. The American representatives were prepared to pay up to $10 million for New Orleans and its environs, but they were floored when the French offered the vastly larger territory to them for $15 million. The American representatives thought Napoleon might withdraw the offer at any time, preventing the United States from acquiring New Orleans, so they agreed without asking Jefferson in advance and signed the Louisiana Purchase Treaty on April 30, 1803. Acquiring the territory doubled the size of the United States, at less than 3 cents per acre.

After the signing of the treaty, Livingston said, "We have lived long, but this is the noblest work of our whole lives.... From this day the United States take their place among the powers of the first rank."

France turned over New Orleans and the territory to the United States on December 20, 1803, at the Cabildo (the Spanish colonial hall) which is next to St. Louis Cathedral, with a flag-raising ceremony in the Plaza de Armas, now Jackson Square.

Jackson Square. The Louisiana Purchase was signed at the Cabildo, the building to the left of St. Louis Cathedral.

The snap purchase sent both New Orleans and the United States on a drastically different course that led to the western expansion and the Civil War. More slave-holding states were created from the new territory, with the help of New Orleans as the main domestic slave market after the United States banned the international slave trade a few years later.

France in actuality had controlled only a fraction of the vast Louisiana territory, which was mostly inhabited by Native American tribes. What France actually was selling was the colonial right for the United States to move into the territory without European colonial interference. The French deal was dwarfed by the $2.6 billion that the United States later paid Native American tribes for sovereignty over the area, a sum that also was a steal. The Louisiana Purchase was an unplanned but momentous event that had massive consequences for not just New Orleans, but all or part of what became 16 U.S. states as well as the fledging United States as a whole. The area also included small parts of two Canadian provinces. It extended U.S. sovereignty across the Mississippi River and almost doubled the United States’ size.

At that point, the non-Native American population of the territory was only 60,000 people, of whom half were African slaves. The French had a few small settlements along the Mississippi and other rivers until they ceded the territory to Spain in 1762. After the French were defeated in the Seven Years’ War, Spain gained control of the territory west of the Mississippi and Britain territory east of the river.

With little clue as to what his country had bought, Jefferson organized three missions to explore and map the new territory. The Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804); Red River Expedition (1806) and the Pike Expedition (1806). The explorers’ maps and journals helped to define the boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase.

The treaty dictated that French, Spanish and free black people living in New Orleans be granted U.S. citizenship. The territorial capital was moved to St. Louis, Missouri, while New Orleans became the capital of the Orleans Territory. The city’s population doubled when French-speaking refugee planters and their slaves as well as other refugees fleeing the slave revolt in Saint-Domingue migrated to New Orleans, bringing a large population of enslaved Africans with them. The French-speaking population were called Creole, but the definition of the word widely varies. Some say it includes only the descendants of those who were in Louisiana at the time of the Louisiana Purchase, while others say that it also includes other populations. It is not necessarily a racial term, as there are different racial groups of Creoles as well as mixed-race Creoles, but the culture is a fusion of the different cultural influences on New Orleans as is the Louisiana Creole language, which has French, Spanish, African and Native American influences. New Orleans’ population had the largest and most prosperous community of free persons of color in the nation. Many were educated, owned property and were middle class. The city was 63 percent black.

The heart of New Orleans is the French Quarter, which is known for its French and Spanish Creole architecture and nightlife especially along Bourbon Street. The French Quarter developed around a central square. Fires in 1788 and 1794 destroyed nearly all the French Quarter, so most of the extant historic buildings were built in the late 18th century, under Spanish rule, or during the first half of the 19th century. The Spanish banned wooden siding in favor of fire-resistant brick, which was covered in stucco and painted in pastel hues. The Spanish also replaced French peaked roofs with flat tiled ones. The French Quarter’s streets were laid out in 1721 and named after French royal houses and Catholic saints. The main street was named Bourbon Street after France’s then-ruling family, the House of Bourbon. The square was a military parade ground and execution site called Place d'Armes in French and Plaza de Armas in Spanish, but is now a public park the size of a city block. It is named Jackson Square after General and President Andrew Jackson. After several hundred slaves participated in the largest slave insurrection in the United States in 1811, some of the participants were executed and their severed heads were displayed at the square.

Three 18th‑century historic buildings are on the side of the square. The center one is St. Louis Cathedral. The first church on the site was built in 1718, and the second was built in 1789. It was largely rebuilt in 1850, with little of the 1789 church remaining. To the cathedral’s left is the Cabildo, the old city hall, now a museum, where the final transfer papers for the Louisiana Purchase were signed. To the Cathedral's right is the Presbytère, originally planned to house the city's Roman Catholic priests and authorities, and adapted as a courthouse after the Louisiana Purchase. It is now a museum. On each side of the square are the matching red-brick Pontalba Buildings, built between 1849 and 1851. They house shops, restaurants and apartments. Live music by street musicians is a regular feature of the Quarter, including the square.

This building on Royal Street has a two-story cast-iron gallery that is a characteristic New Orleans architectural feature. The development of New Orleans’ famous ornate cast iron 'galleries' began with those on the Pontalba Buildings on Jackson Square, completed in 1851. They set a trend, and multi-level cast iron galleries replaced old timber French ones on older buildings as well being placed on new ones. Below, a colorful stucco building, a style that is a legacy of the Spanish.

Along Bourbon Street are other historic buildings. The French Quarter also has a number of well-known restaurants such as Antoine's and Tujague's which have been in business since the 19th century or are run by famous chefs. There also are a number of hotels, including ones that have small guest houses with one or two rooms. The Ursuline Convent (1745–1752) is the last intact example of French colonial architecture. Of the structures built during the French or Spanish colonial eras, only 25 survive. Two-thirds of the French Quarter structures date from the first half of the 19th century, the most prolific decade being the 1820s. Many are Creole style.

Many Southern slaveholders feared that acquisition of the new territory and the influx of slaves from Haiti might inspire American-held slaves to revolt. The slaveholders wanted the US government to establish laws allowing slavery in the newly acquired territory so they took slaves there to work in new agricultural projects.

The institutionalization of slavery under U.S. law in the Louisiana Territory contributed to the Civil War a half century later. As states were established within the territory, the status of slavery in each state became a matter of contention in Congress. Southern states wanted slavery extended to the west, and northern states opposed new states being admitted as slave states.

The British sent 11,000 troops to capture New Orleans during the War of 1812. Andrew Jackson successfully brought together militia from Louisiana and Mississippi, including free men of color, U.S. Army regulars, Tennessee state militia, Kentucky riflemen, Choctaw fighters, and local privateers (the latter led by the pirate Jean Lafitte), to defeat the British in the Battle of New Orleans in 1815. An equestrian statue of Jackson is in Jackson Square.

The new U.S. government also fought wars in the territory and built forts on the Missouri and Mississippi rivers to establish control of the area. During the War of 1812, U.S. forces fought British and allied Native American forces along the Mississippi. Native American tribes in the area included in the Louisiana Purchase were not consulted during the negotiations with France and four decades of court decisions, treaties and conflicts ensued before many tribes were removed from their lands east of the Mississippi.

New Orleans prospered as nearby large plantations grew sugar and cotton for export. New Orleans was an Atlantic slave trading port and goods also were warehoused and exported from the interior of the territory through New Orleans. Imported goods warehoused there were transferred to smaller boats for distribution along the Mississippi River, which had heavy steamboat, flatboat and sailing ship traffic.

New Orleans had the nation's largest slave market during the antebellum era, with the domestic market for slaves expanding after the United States banned international slave trade in 1808. The trade spawned an associated economy in transportation, housing, clothing and fees that made up 13.5 percent of the price per person. New Orleans was a prime beneficiary. Louisiana's slavery was notorious even in the South for its appalling brutality, especially on plantations.

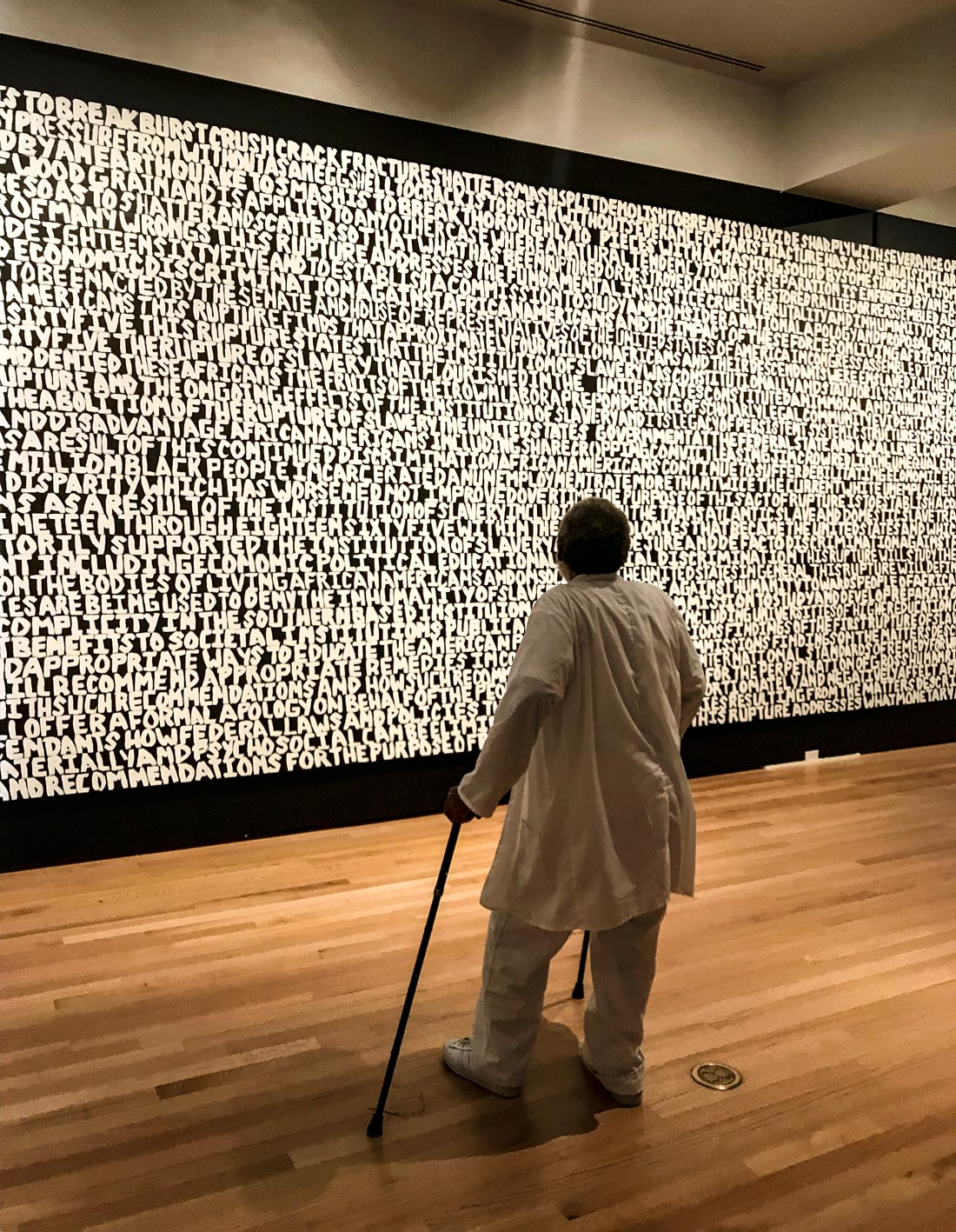

The tragic history of slavery and the long struggle for civil rights in Louisiana continued for centuries. Its sadness and anger flows through the vibrant art, music and literature of New Orleans.

French speakers were a majority of the white population until almost 1830. As Anglo Americans migrated to New Orleans, the city's population doubled in the 1830s. By 1840, it was the nation’s wealthiest and third-most populous city after New York and Baltimore. German and Irish immigrants started arriving in the 1840s to obtain work as port laborers. In the 1850s, two of the city's four school districts taught in French. In 1860, the city had 13,000 free people of color. They set up private schools for their children. The census recorded 81 percent of the free people of color as mulatto, a term used to cover all degrees of mixed race. They included artisan, educated and professional classes of African Americans. Most African Americans in the city were enslaved and worked at the port, as craftsmen or domestic servants, or on surrounding sugarcane plantations.

New Orleans by 1840 was the third-most populous city in the United States. It was the largest city in the American South until after World War II. The city grew 45 percent in the 1850s and by 1860 had nearly 170,000 people. It had the second highest per capita income in the nation and the highest in the South.

Louisiana followed the Confederacy in seceding from the Union, but that didn’t last long – the Mississippi River was too important for the Union not to make it a main target. The Civil War started in 1861 and Northern forces occupied New Orleans in 1862. Because the city was occupied so early, it was spared destruction and still has antebellum buildings. From New Orleans, the Union Army extended control north along the river and coastal areas. Many rural ex-slaves and some free people of color from New Orleans volunteered for the war’s first regiments of black troops under the French title Corps d’Afrique.

Union General Benjamin F. Butler, who imposed military rule on the city, abolished French instruction in the city’s schools. By the end of the 19th century, French usage had declined, but a fourth of the city still spoke French in daily conversation, and half could understand the language. As late as 1945, many elderly Creole women spoke no English. My father, who was from a French American family, related how much he enjoyed the hospitable French Creole people of New Orleans when he was stationed in the military in Louisiana.

For a brief period after the Civil War, both blacks and whites were elected to local and state offices in Louisiana, including a mixed-race governor, and public schools were integrated. However, an insurgent white paramilitary group called the White League tried to suppress black voting through violence. In 1874, in the Battle of Liberty Place, 5,000 members of the White League fought with city police to take over the state offices for the Democratic candidate for governor, holding them for three days. Such tactics resulted in white Democrats regaining political control of the state legislature. Federal troops withdrew in 1877, ending Reconstruction.

White Democrats passed Jim Crow laws establishing racial segregation in public facilities and disenfranchising freedmen and propertied people of color who were manumitted before the war. African Americans were shut out of politics for generations. New Orleans' large community of well-educated, French-speaking free persons of color fought Jim Crow, but were unsuccessful in protecting their civil rights until the 1960s. When six-year-old Ruby Bridges integrated William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans in 1960, she was the first child of color to attend a previously all-white school in the South. From 1980 on, the African-American majority in New Orleans elected primarily officials from its own community.

After the Civil War, New Orleans' importance declined as railways and highways decreased river traffic.

World War II brought thousands of servicemen and war workers to New Orleans as well as to the surrounding region's military bases and shipyards, where the famous Higgins landing boat used by the U.S. army was manufactured. The war produced the city’s exotic, risqué, and raucous entertainment on Bourbon Street. Thousands of people of color left in the Great Migration in and after World War II. As the middle class and wealthier members of both races left the center city, its population's income level dropped. New Orleans has since become increasingly dependent on tourism.

New Orleans has many festivals, the most famous of which is Mardi Gras, a raucous two-week festival in the early spring that includes parades of elaborately and colorfully dressed participants and floats. The festival has been celebrated since 1699 with masks, costumes and dancing. The population of the city more than doubles during Mardi Gras.

A post-Mardi Gras sale.

New Orleans is a dress-up city. Here, a group of people in oversized cowboy hats and western belt buckles dance on a street.

New Orleans is known for its vibrant art scene.

The city’s low location and flat elevation has made it vulnerable to flooding, and the city developed a complex system of levees and pumps to protect it from flood and drain large tracts of swamp and marshland in low-lying areas. The federal levee system failed during Hurricane Katrina on Aug. 29, 2005. Most residents had evacuated, but 80 percent of the city flooded. Tens of thousands of residents who had remained were rescued, but more than 1,500 people died in Louisiana, mostly in New Orleans. Some remain unaccounted for. It was the worst civil engineering disaster in American history.

As a result, the population declined by more than 50 percent. Hurricane Rita in September 2005 reflooded the city. The population was back up to 80 percent of its pre-Katrina level by 2015.

Today, half of the city is at or below local mean sea level, while the other half is slightly above sea level. Evidence suggests that portions of the city may be dropping in elevation due to sinking. Some areas are as much as seven feet below sea level. New Orleans is built on soft sand, silt, and clay. In the past, flooding and deposits of sediments from the Mississippi River counterbalanced the natural sinking. However, because of flood control structures built upstream on the Mississippi River and levees built around New Orleans, fresh layers of sediment are not replenishing the ground lost.

Because of the high water table, New Orleans has elaborate European-style cemeteries with above-ground stone tombs.

New Orleans is famous for its many architectural styles. Bungalows, creole cottages and townhouses with large courtyards line the streets of the French Quarter. St. Charles Avenue is known for large antebellum homes in various styles. The oil boom of the 1970s and early 1980s redefined the central business district’s skyline with highrises such as One Shell Square.

Check out these related items

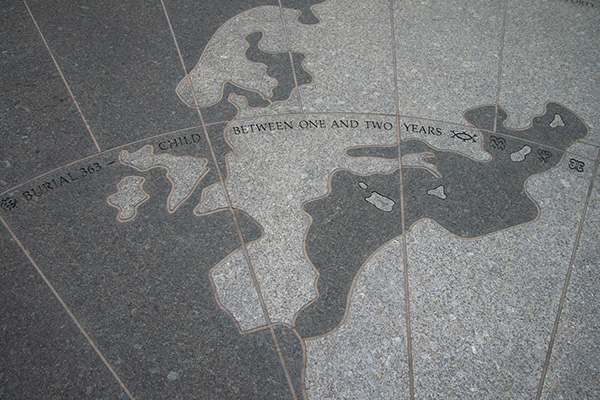

Memorial to Once-Forgotten People

A moving monument and burial ground in Manhattan comemorates enslaved people who once made up more than a third of New York City.

Mountain Men and the Fur Trade

The colorful annual mountain men rendezvous at Fort Bridger, Wyoming, commemorates the 19th century global fur trade.

The History of Race in America

The racial history of the United States belongs to us all, with the responsibility to resolve the accompanying outstanding problems.

The Racism of Confederate Statues

The racist past associated with the Confederacy and Confederate monuments has a complex history.

Wolf in Ship’s Clothing

The picturesque town of Bristol, Rhode Island, once was a slave port and home of the nation's leading slave traders, the DeWolfs.