Enchanted Land, Part 2

Photos by Forrest Anderson

My ancestors’ stone houses in southern French villages are hundreds of years old. The French are among the world’s best at renovating and updating old buildings so that they work for new generations, and these houses have been repeatedly repaired, rebuilt, modified and updated with modern plumbing, electricity and other modern conveniences over generations.

The birthplace of my great grandfather, Jean Cyprien Rouviere, is currently undergoing such a renovation. He was born in 1842 in the tiny seven-family community of Depoudent high in the Rhone-Alps. The maire or mayor of 15 of the tiny communities in the area, Michel Broche, kindly took us to Depoudent to see the house where my great grandfather was born.

A 93-year-old cousin in a black beret and coat, Noé Chat, was busy burning a large pile of branches on one of the steep terraced areas below the road where old records say that my ancestors worked the land as “cultivateurs” or farmers. Noé shook hands and I showed him pictures of my American branch of the family, ranchers mounted on horses and wearing cowboy hats.

“Ah, chevaliers (a word that can translate either as horsemen or knights),” he commented. “Américains!”

Noé Chat.

Noé guided us around the outside of the stone house where my great grandfather was born, which shares a wall on one side with his family’s home and a wall on the opposite side with a family named Hermitant who also figure prominently in my family’s records. A back wall of the Rouviere home that had collapsed was being rebuilt using modern construction methods, a terrace had been added and other renovations were under way. Just down the road are the stone homes of another branch of the family.

My great grandfather's birthplace.

This constant process of updating old structures while retaining their historical integrity has made France one of the world’s leading countries in historical renovation. The French way of renovating historical sites is to blend the old and new together gracefully with respect for both. This charming ability to live so beautifully with their past is part of makes France the most visited country in the world.

From the outside, the old communities of stone houses in this region look like the small fortresses they once were, with small shuttered windows and thick stone walls shared with neighbors. Inside, the structures are French country homes with wooden roof beams, fireplaces, creamy white walls, simple but beautiful wood furniture and blue or terracotta tiles.

We stayed in one such stone house in one of my family’s villages, an AirBNB in Faugeres run by Anais Vincent, who is a relative through the Roustangs. We opened the door of this quaint house with a huge old-fashioned brass key to be greeted by a warm fire crackling in a French fireplace under a ceiling of polished chestnut beams restored by family member Bruno Vincent. On the table was a bottle of delicious apple juice from Provence. A gorgeous view of the mountains could be seen through the wood framed windows set into the thick walls.

Everything in this rocky, forested region is made of stone and wood, the two most readily available materials. The thick walls are built of stacked stone and the roofs of large wooden beams cut from the trees on the mountainsides.

Roofs are covered with either ceramic tiles or, in the case of older buildings, slabs of stone.

A stone chimney on a stone-tiled roof.

Even garages are stone structures, some of which are the remains of structures that once housed animals or stored food.

Old Records

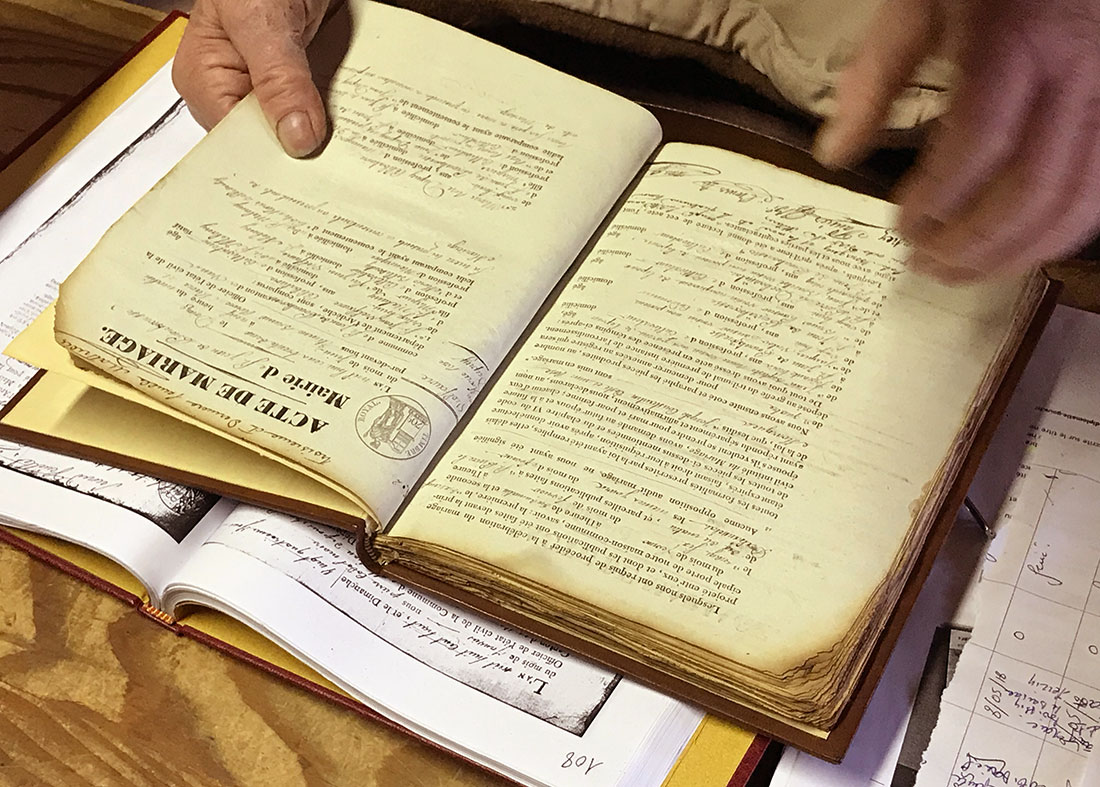

Monsieur Broche kindly took us into the mairie or town hall in the village of St. Jean de Pourcharesse, where all of the area’s civil records back to 1790 fit on one shelf of a large wooden cabinet.

He opened the old leather books in which were recorded births, marriages and deaths of the people of the village.

Mr. Broche copied for us a stack of documents that trace my family’s Rouviere line back to the French Revolution.

The earliest records in the local villages are from after the revolution, Monsieur Broche told us, so we stopped at the archives in the nearby administrative center of Privas to ask about earlier records. The archives were closed, but an archivist who happened to be there responded, “Oh, yes, we have medieval records.”

She handed us a pamphlet with her email on it. Write and ask what we wanted to know and she could research it, for a fee if the search was time consuming, she said.

The area’s records go back through the state civil records to Catholic parish records and a few Protestant records, then into notarial records and feudal records, gradually diminishing the further back they go. There even are some Latin records from the Roman Empire, although it’s unlikely I would be able to trace my specific family line back that far. I have been able with very minimal effort to trace my family to 1455, but I’m pretty confident I could trace them further back with more work.

Lucky is the family historian with French ancestry. French records are superb – a marriage record, for example, will list the names and ages of the bride and groom, their parents’ names and whether the parents are deceased, what small community the newlyweds live in and their occupations. If one of the newlyweds was a widow or widower, sometimes earlier spouses also will be listed. There is always a list of witnesses, with ages, sometimes where they lived, their occupations and their relationship to the couple getting married. Birth and death records have similar helpful details. It is even possible to find out what time of the day your ancestor was born in the 1700s.

The major challenge with the records is that not all of the older ones are on line, but the Archives Nationales is digitizing and placing on-line an ever growing number of records.

Cracking the Code

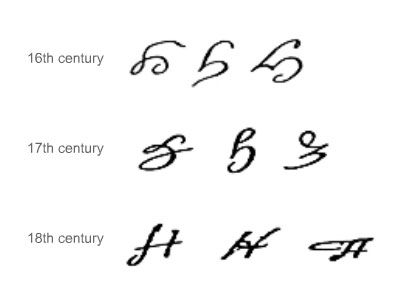

The other main problem with the records is that copies of some records on-line are unclear, and the handwriting is not easily deciphered without special training, especially with records dating back to the 16th century and earlier. We've found that the best way to handle this problem is to become familiar with the 18th century names in the records first. This enables us to then recognize the names despite the difficult handwriting as we move backward in time.

This is an example from familysearch.org of various forms of the letter H as it was written throughout French history. Researchers need to first crack this code, as they can otherwise make mistakes in transcribing letters.

Other problems include deciphering French dates, as it is essential to understand the French number system of counting by 20s rather than 10s from 60-99. The French calendar also changed dramatically, with different lengths of months and names for months for a 12-year-period after the French Revolution, so dates during this period need to be converted.

Fortunately, the records are so good that with training, even non-French speakers can read the records. We found that government officials such as Monsieur Broche, people at the local tourism office and at the archives in Privas were extremely helpful, patient and kind despite my very poor French. When they could speak English, they chimed in cheerfully to help me out.

A Frenchman in Paris who spoke excellent English thanked us for our clumsy efforts to speak French, however. "I can speak English, of course," he said. "But still, we appreciate it when you make the effort to speak French in our country. It shows respect for us."

I found that even my terrible French opened doors and that it was essential in southern France where many people don't speak English. I was amazed at how patient people were when my small vocabulary failed and we had to rely on Google Translate to make requests and understand their replies.

Cemeteries and Monuments

In the cemeteries in the villages of St. Jean de Pourcharesse, nearby Faugeres, Sablieres, Planzolles and Joyeuse, we found dozens of gravestones inscribed with family surnames. French gravestones can be helpful in family history research for the late 19th and 20th centuries because a list of ancestors and their birth and death dates in chronological order often is inscribed on them. Most gravestones date back no further than the mid-19th century, however.

Near the churches in each village are war monuments from the first and second world wars inscribed with the names of many of my relatives who were killed in the wars. For years after the two wars, my American relatives thought that all of the family in France had been killed in the wars. It’s no wonder. Considering that most of the villages only had 100-200 people, the number of dead listed on the monuments must have been particularly devastating.

Into the Wild (Driving, That Is)

It’s hard to argue that heading into this high mountainous area of southern France was, in the sense of the hobbits and Aragorn in Lord of the Rings, going “into the wild” when everyone we met had smart phones and the television was on at our AirBNB upon our arrival.

In one sense, however, the phrase more than applied – the roads and driving. My ancestral villages are perched on steep cliffs accessible only by precarious narrow roads that sharply hairpin through the mountains. There are blind corners every few feet, and local drivers nonchalantly careen around them in the middle of the road. If we met another car on a road, we both screeched to a halt. They or we, whoever was closer to a turnoff, had to back up until an equally narrow and steep side road appeared, allowing one car to turn off so the other one could go by. In villages, tall stone walls on either side of the roads gave rise to fears of carving a racing stripe the length of our rental car. Despite having driven for years in Asian cities with narrow walled lanes, we found this the most harrowing driving experience of our lives. It was with immense relief that we finally turned the car in unscathed to Hertz in Lyon.

A narrow village street with stone walls on both sides.

Check out these related items

Enchanted Land, Part 1

A search for ancestral roots in southern France leads to a legendary land with a walled medieval town and tales of a magic sword.

A Tale of Two Roman Cities

The amphitheaters, military garrisons, forums, trade and craft shops of two Roman colonial cities have emerged from the dust.

The World Mourns Notre Dame

Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris, France's national cathedral, was badly damaged in a fire.

Paris’s Oldest Church Restored

Paris' oldest church, Saint Germain des Prés, is emerging from layers of grime and soot as a meticulous restoration reveals its vibrant color.

Marie Antoinette and Barbie

Since she was guillotined in the French Revolution, Marie Antoinette has become one of the most popular icons worldwide.

Paris’s Oldest Food Market

Rue Montorgueil in Paris began as a village street with a medieval church and food market. It has retained that character.