Resting Place of Kings

Photos by Forrest Anderson

Once upon a time, in a kingdom far, far away, the last of a long line of kings was overthrown after almost a century of intermittent revolution, and a republic was founded. The question arose of what was to be done with the many dead kings’ tombs.

Those who governed this land, France, appreciated that this was a tricky question because early attempts to destroy the tombs along with other vestiges of the monarchy had prompted a significant backlash that had helped to restore the monarchy temporarily to power.

Moreover, the French kings had bankrolled one of the world’s greatest art heritages, of which the French people and the world were justifiably proud and fond of. The tombs were part of that heritage.

The solution was to keep the kings’ tombs in safe and impotent splendor in a large medieval church in a suburb of the capital city, Paris, while the country got on with the business of democracy.

Fortunately, the Basilica of Saint-Denis was not only at hand but it had an impeccable historical and archeological legacy because almost every French king from the 10th to the 18th century had been buried there, along with many from previous centuries. French queens also had been crowned there.

It is at Saint Denis that the mythology and history of the Christian kingdom of France merge in one of the most splendid displays of funerary art in Europe, housed in the birthplace of Gothic architecture.

Saint Denis was the abbey church of a Benedictine monastery that was intimately associated with the royal court for centuries. So intertwined with the history of France is the church that its monks for many years wrote the kings’ chronicles. Much of this story is legend which the monks embellished over the centuries, making it difficult to discern what is fact and what was carefully constructed myth shaped by the monks and others who were trying to strengthen their influence in the royal court.

Here’s how the traditional narrative of Saint Denis goes:

Beneath the basilica lies an ancient Gallo-Roman cemetery used by people whose beliefs were a mix of Christian and pre-Christian beliefs. A document from about 600 related the tale of a Christian named Denis, a follower of the Apostle Paul, who was sent from Italy to convert the people of Gaul in the 3rd century. It wasn’t until the 9th century, 600 years after Denis lived, that this story was fleshed out in the writings of the abbot of Saint Denis, Hilduin.

Denis was appointed the first Christian bishop of Paris and got to work along with two companions on the Ile de la Cité that is the heart of Paris. Their success at gathering converts alarmed non-Christian priests in the area who were losing followers, and the priest reported the Christian missionaries to the Roman governor. He obligingly arrested the three, imprisoned them for a long time and then beheaded them on Paris’ famous Montmartre hill. Here, the story turns mystic, but in a pattern that was fairly common in accounts of martyred saints. Denis refused to die, picked up his severed head and marched off to the current site of Saint Denis church with his head, which continued to preach and sing on the way. Some later 13th century accounts say he lost only the top of his head. This was not as unusual as it sounds – there are many legends of early Christian saints’ heads continuing to speak and their bodies to function for a time after beheadings.

Denis died at the site where today’s church was built. Supposedly, Roman soldiers intended to toss the three missionaries’ bodies into the Seine, but were distracted by a Christian woman who got them drunk and then had the bodies buried at the site. Wheat was planted over them to hide the graves.

Around 331, the date that the Emperor Constantine ended the Roman war on Christians, a small chapel was built as a shrine on the site.

Roughly two centuries later, a wealthy woman named Genevieve, known for saving Paris from Attila’s Huns in 451 with a prayer marathon and diffusing a siege of Paris by Germanic King Childeric in 464, bought the land where the grave was. She is believed to have built the first church on the site, which over time became the abbey church of a large, influential monastery. Genevieve was canonized as one of many early Christians who were added to the roster of saints. Denis and his companions also were canonized.

A cult of sainthood arose in which people made pilgrimages to churches associated with canonized martyrs. Relics associated with them such as bones, belongings or other items associated with their martyrdom were placed in elaborate reliquaries in churches and many people believed that devotion to a saint could afford them divine protection. It was common for bodies of saints to be divided up and displayed at different shrines to spread the saints’ miraculous power.

Servicing the many pilgrims who flocked to the shrines became profitable, and some abbeys such as Saint Denis became wealthy. The town of Saint Denis that grew up around the shrine prospered, partly because of several annual trade fairs associated with the church.

Many high-ranking figures, especially women, were buried close to the church of Saint Denis. Queen Aregund, who died around 580, was the first royal to be buried at the church and her grave was discovered in 1959. She was dressed in Constantinople silks, earrings, garters and gold brooches adorned with garnets. Her burial jewelry is in the Musée d'archéologie nationale du Domaine de Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

The queen was the great grandmother of King Dagobert I (c. 603-639), who united Frankish society and made Paris his capitol.

French kings were interested in saints’ relics and in courting favor with saints to add to and demonstrate their own power and protection from rivals. King Dagobert became one of the core legends associated with Saint Denis and the church. He was said to have had a vision in which martyrs appeared to him and promised to help him if he would build a church. They also pledged that Christ would personally dedicate the church the evening before its official consecration. Dagobert is credited with building the Saint Denis basilica at the site of the abbey church, and the legend was that Christ did appear with Saint Denis and angels and healed a leper at the church site before consecrating the church.

The high altar at Saint Denis, which honors Saint Denis and the other two saints who were martyred with him.

In later years, Dagobert’s throne became associated with the church and apparently was kept in Saint Denis from at least the middle of the 12th century . The priest who celebrated the mass at the high altar sat in it. The folding bronze chair, which is now in the National Library, has been dated to the 8th century, after Dagobert I’s death, but it still has retained significance as a symbol of royal authority. Napoleon I sat on it during a Legion of Honor ceremony in 1804.

Dagobert’s body was interred in the basilica in 639 and his son, Clovis II (657), was as well. This established the tradition of kings being buried at the church.

Dagobert's current tomb at Saint Denis, which was built in the 13th century, long after his death.

Saint Denis became known as the patron saint of France. For kings, burial at Saint Denis enhanced their legitimate right to rule. The three martyred saints were thought to help them obtain power and protection, especially in battle and in enabling their direct ascent to Heaven after death. A minority of royals were buried at other churches, but several such as Charles Martel (741) were especially devoted to Saint Denis. His son, Pepin the Short (768) was buried face down at the church in penance for the sins of his father.

Dagobert had a marble canopy placed over Saint Denis’ mausoleum, which he had decorated with golden apples and other gold embellishments, precious jewels and a silver gate. One account said that the tomb was so elaborate that “scarcely a single ornament was left in Gaul and it is the greatest wonder of all to this very day.” However, the mausoleum no longer survives.

Dagobert is problematic because his life was embellished with new stories with every generation as part of the cult centered on Saint Denis. Monks of the abbey promoted the story of the union between the kings and the shrine, particularly when they felt their influence with the kings was waning.

King Pepin the Short, who was anointed by a pope at Saint Denis to seal an alliance with the papacy, began to expand the church in 754. Pepin was the first Frankish king to be crowned as the image of God on earth in the manner of the Biblical King David. Pepin’s Roman-style version of the church had paint work imitating marble that can still be seen. This project was completed under Charlemagne, who attended its consecration in 775. The building became a basilica, given to churches that were major pilgrimage sites.

The connection between the royal court and the basilica solidified until the church became the official royal burial place in the 10th century and one of the most powerful Benedictine abbeys of the Middle Ages.

The scarlet banner of Saint Denis, called the Oriflamme, was the French kings’ battle banner in the 12th and 13th centuries. Dagobert was said to have given the banner to the abbey. Kings received communion at Saint Denis before going to battle and then borrowed the banner to take with them. When the kings raised the banner in battle, especially during the Hundred Years War, no prisoners were to be taken until it was lowered. The goal was to frighten the enemy, especially nobles, who expected to be taken alive for ransom in battles. The legend arose that Charlemagne had carried the Oriflamme to the Holy Land in response to a prophecy about a knight with a golden lance from which flames would shoot and drive out the enemy. The silk banner was flown from a gilded lance. Bearer of the Oriflamme was an official court position and poems were written about the banner.

A battle cry, “Montjoie Saint Denis!”, was inscribed on the banner along with golden flames. This became the motto of the kingdom of France. A 1913 copy of the banner is at the basilica. There are a number of theories as to what “Montjoie” meant, none of them definitive. The standard and battle cry became main objects from the medieval era that evoked the first notions of “nation” in France.

In the 12th century, the church’s Abbot Sugar was so influential that he became a close friend of two French kings and served as regent for Louis VII, governing France while the king was on the Second Crusade from 1147-49.

Suger’s hand was in a number of these key symbols as he jealously guarded the church’s legendary connections with Dagobert and thus with the royal family.

In 1130, Suger developed a complex architectural plan to expand the church, bringing together techniques used in different areas to create an open, light-filled building that could better accommodate the huge crowds of pilgrims at the church. He conceived of the church as a Heavenly Jerusalem, with two towers linked by a crenelated parapet on the front façade. The central door was surrounded by sculpture representing Christ enthroned in the Last Judgement, judging those who passed through the Gates of Heaven into the church.

The Last Judgment main portal of the church.

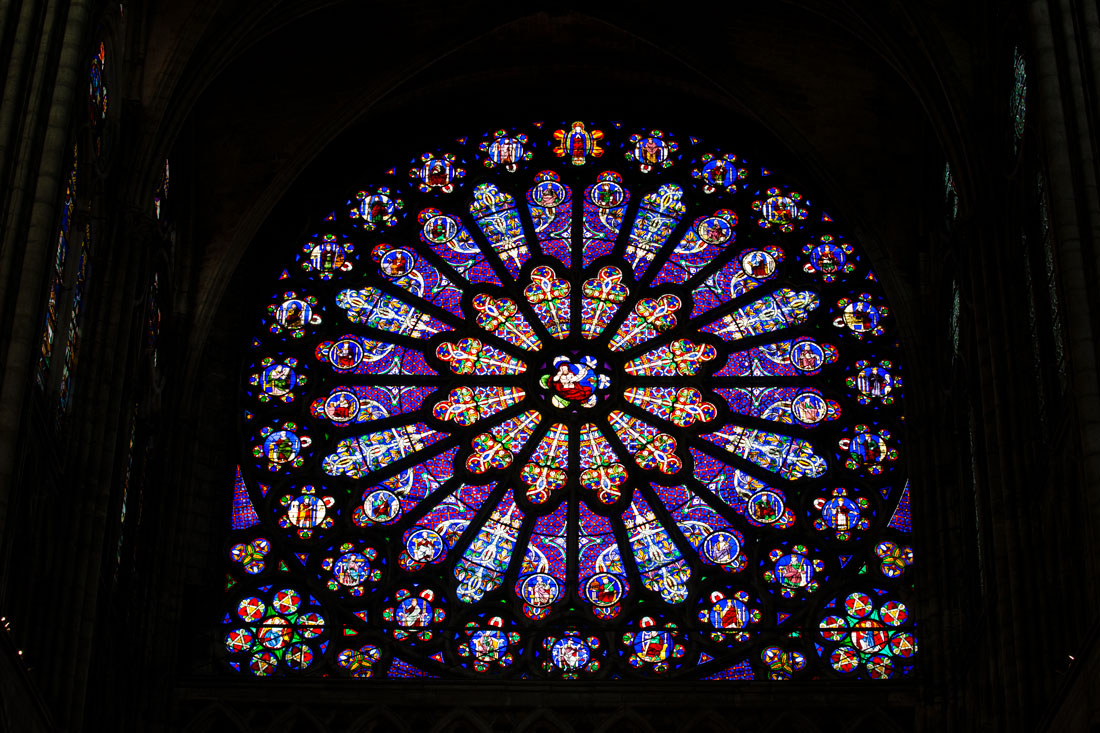

Inside the church, Suger and his architect combined already-existing techniques– rose windows, cross-ribbed vaulted arches, clustered columns that rise to match the vaults. The effect is to draw the eye upward so that the roof appears much higher than it is. The use of flying buttresses enabled an open space with a minimum of wall area and large stained glass windows that fill the space with dazzling colored light meant to invoke spiritual wonderment. Large rose windows in the church were precursors to the rose window at Notre Dame and those in other Gothic cathedrals.

This exterior photo of the church shows one of the rose windows and the flying buttresses that enabled the airy, light filled interior.

In 1144, the apse of the church was consecrated in a procession led by King Louis VII and Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine. About 20 bishops, abbots and the papal legate transported the three silver reliquaries of the holy martyrs from the church’s crypt to the apse. The altar, which was gold and silver, has since disappeared, but the 19th-century altar still houses three reliquaries containing bones.

Sugar died in 1151 before the project was completed but further construction work starting in 1230 under the reign of Saint Louis IX completed it in its current form. The church is considered the birthplace of the transition from Romanesque architecture into Gothic architecture. It became the model for other Gothic churches such as Notre Dame de Paris, elsewhere in Europe and eventually around the world.

The church is a large cross-shaped building with a central nave, aisles, high walls with stunning stained glass windows and a north side that forms a row of chapels. It has exquisite stained glass windows from many periods. The light-filled church is one of the era’s most beautiful achievements.

Few windows remain from Suger’s day, but the 19th century windows still recount the legend of Saint Denis and history of the basilica as well as a gallery of kings and queens. The South Rose Window depicts a central figure of God, angels, the twelve signs of the Zodiac and 24 annual agricultural tasks. It is one of two spectacular rose windows and probably the first rose window with a circular frame, which became the dominant feature of Gothic churches of northern France. Suger is thought to have been influenced by the teachings of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, a 6th-century mystic who equated the slightest reflection or glint with divine light.

Tall statues of Old Testament prophets and kings, which became a standard feature of Gothic portals, are on the façade. Most of the sculpture now on the church is reproductions added in 1839. Only fragments of the original sculpture exist and are in Paris museums.

Sugar delighted in the basilica’s treasury, which contained items bequeathed by wealthy abbots or kings to Saint Denis, and was one of the Middle Ages’ largest. He added to the jewel-encrusted and gold items in the treasury, adorning the church’s altars with them. The items also were considered monetary reserves for the abbey. The treasury also kept the crowns, scepters and hands of justice used in coronations. Several of the pieces are now in the Louvre, the Bibliothèque and foreign museums. The treasury included crowns of Charlemagne, Saint Louis, and Henry IV, a cross and liturgic objects.

Beginning in 1231, under King Louis IX who was canonized as Saint Louis, there was an upsurge in royal interest in creating a royal necropolis on which the kings could rest their claims of privilege and dynasty. Saint Louis ruled when France was at its height in Europe, politically and economically. France had Europe’s largest army, was its largest and wealthiest kingdom, and was the continent’s center of arts and intellectual thought. Saint Louis’s court style spread throughout Europe because of the export of art objects and the marriages of the king’s daughters and female relatives to foreign royals. Saint Louis also was famed for his benevolence, and considered a model Christian prince.

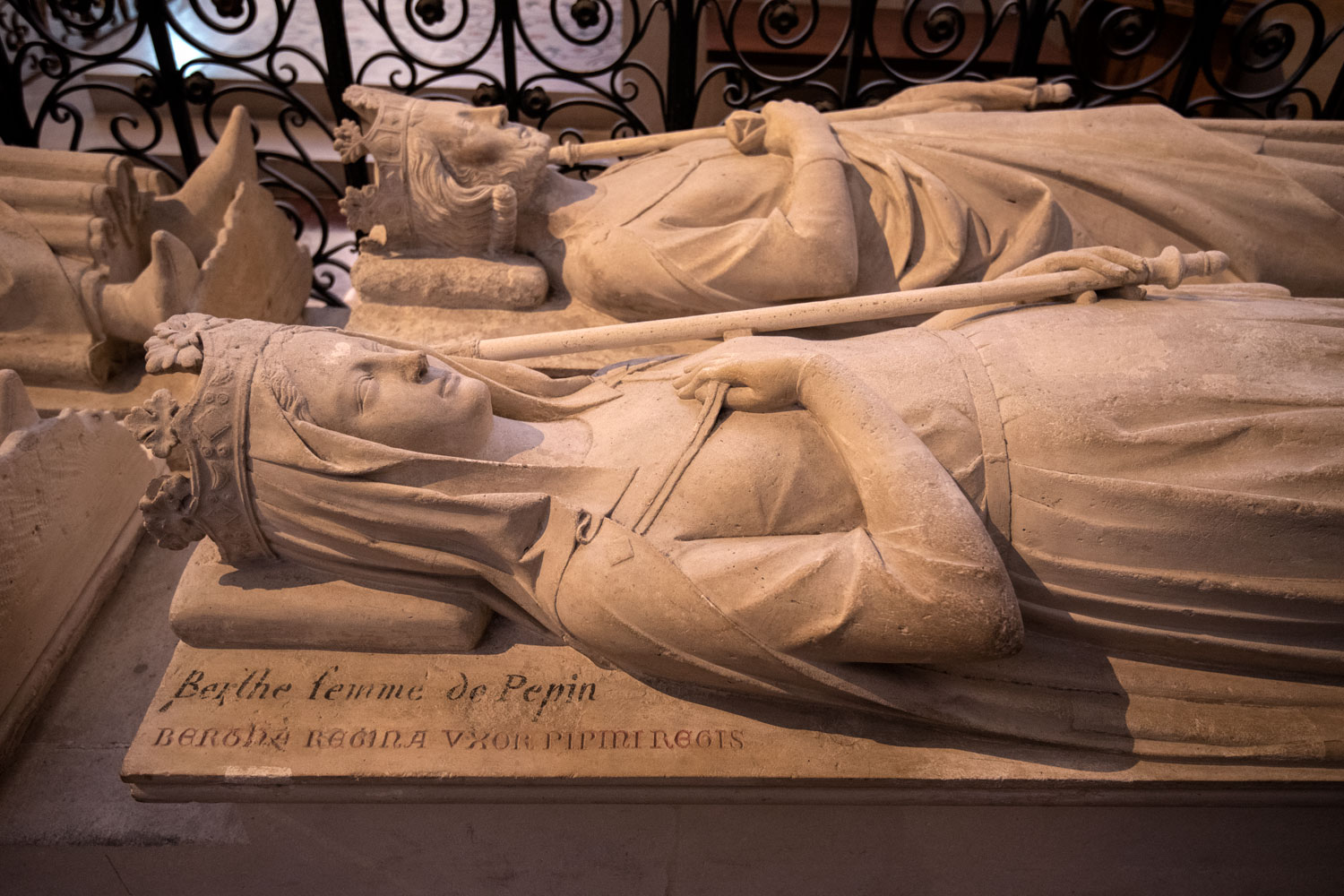

The abbey built 16 tombs of past kings and queens with statues of the dead royals atop them and relocated their bones to the tombs. Fourteen of the tombs remain and are the largest series of funerary sculptures of the European Middle Ages. Before these tombs were being placed in the church, only engraved stone slabs on the floor near the altar marked the location of royal burials. The new tombs included eight Carolingian monarchs on the south and eight Capetians on the north of the church. This associated the reigning Capetians with the Carolingian past, as King Philip II claimed the title of New Charlemagne. The effigies were originally painted in bright colors and dressed in 13th century fashion, with their eyes open to convey a belief in the Resurrection. The sculptures were a device to develop the notion that Louis IX’s lineage went back to the Merovingian, Carolingian and Capetian dynasties and that his family was linked to Charlemagne, who was the most impressive figure in medieval monarchical ideology.

The tombs of kings and other royalty.

The inscriptions on the tombs identify the kings and queens and their genealogies. During the Middle Ages, the gilded silver tombs of Louis VIII and Philip Augustus, Louis IX’s grandfather, were in the center. The idea was to link Saint Louis’s heritage to both the Carolingian and Capetian dynasties. His father was Capetian and his mother, Isabella of Hainaut, was touted as being of Carolingian ancestry. The idea was to show through this sculptural genealogical chart that the race of Charlemagne had returned to the throne of France. This was crucial for Saint Louis, because Saint Valery had prophesied in the 11th century that the Capetian kingdom could be maintained only up to its seventh king, who was Saint Louis’ grandfather Philip Augustus. He needed the Carolingian blood of his mother to maintain his hereditary legitimate right to the throne. Saint Louis apparently was distantly descended from Charlemagne, for what it’s worth, but Charlemagne had 18 children and such a prodigious number of descendants that his distant relationship with Charlemagne wasn’t much of a claim to royal legitimacy. This wasn’t the first or last time that Charlemagne’s cult was used to shore up kings’ prestige. Napoleon used Charlemagne much later in his propaganda.

The central chapel of the church was decorated around the theme of the tree of Jesse, Christ’s genealogy in the Gospel of Matthew, reinforcing the idea that the kings were the image of Christ on earth.

The tomb inscriptions include legendary names of the past – Philip III the Bold, Isabella of Aragon, Philip IV the Fair, John II the Good, Childebert, and others along with the Lord of the Rings-style stone effigies. The tombs installed during Saint Louis’ reign were in 13th century dress rather than that of their own times, and they were fairly uniform in appearance. From 1285 on, however, the statues’ faces were copied from sovereigns’ death masks and became interesting portraits of the kings.

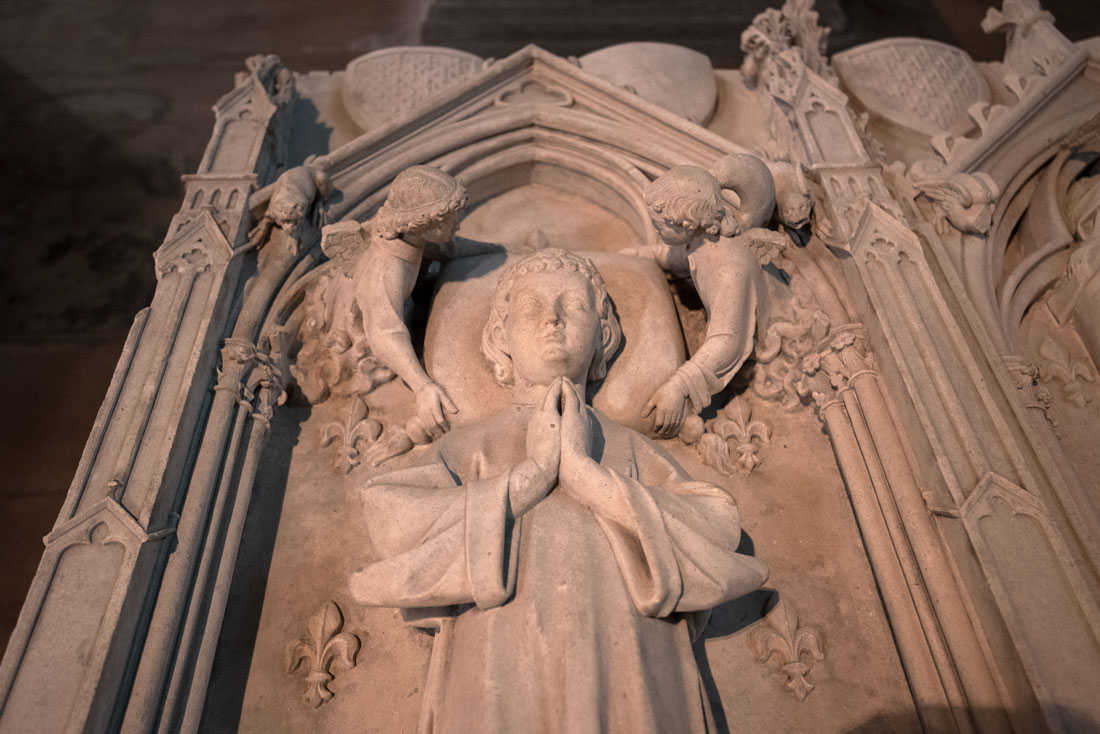

The sculptures, most of which are lying down, are replete with symbolism. Some have dogs at their feet symbolizing fidelity and their role of guide dogs in the subterranean realms of death. Lions, usually at the feet of kings, represent power, strength and the Resurrection, because lion cubs were believed to not open their eyes until three days after birth. Angels hover over some of the dead, adjusting their pillows.

One of the kings rests his feet on a lion, symbol of his authority.

Angels adjust the pillow of one of the statues.

The Saint Denis monastery library in the Middle Ages was the largest in the kingdom. At Saint Louis’ request, it translated a large set of texts into French to create the first official chronicles of France’s history, called the Grande Chroniques de France. These texts associated the Capetian dynasty with the ancient origins of the Frankish kingdom.

Among the famous tombs at the church are:

Saint Denis’s remains. In 1052, monks from another abbey claimed they possessed Saint Denis’ body and organized a celebration which the emperor and court of Germania attended. The monks of Saint Denis appealed to the then-king of France, Henry I, who ordered the shrine at Saint Denis opened in the presence of numerous bishops so they could confirm that Saint Denis’ body was inside. The relics were moved to the town parish church in 1795, but returned to the basilica in 1819.

The tomb of King Charles V was the first official portrait in funerary sculpture and is a masterpiece of medieval sculpture.

Two-layered Renaissance-style monuments. There are three – the tombs of Louis XII, Francis I and Catherine de Medici. On the lower level, the bodies of the sovereigns are naked, lifeless and in the agony of death. On the upper level they are dressed in court dress and kneeling in prayer.

These tombs probably were an outgrowth of funeral ceremonies of the era. When the king died, a funerary effigy of him was created with a face in wax, which was provided with solemn meals several times a day. This model was meant to represent the monarchy’s permanence. The coffin was placed inside a catafalque at burial, and the effigy was placed on another platform.

The two-layered tomb of Louis XII (1462-1515) and Anne of Brittany (1476- 1514), was the first of its kind. In the lower part, sculptures of their emaciated bodies are in the agony of death, with protruding ribs, distended veins and even roughly sewn up bellies that were opened to remove organs before embalming. On the upper layer of the tomb, they are shown alive and cloaked as they kneel in prayer.

This tomb is surrounded by the twelve apostles and the four cardinal virtues, Prudence, Justice, Fortitude and Temperance. The bas reliefs illustrate victorious episodes of the Italian wars of the time in a common pattern of celebrating aspects of rulers’ lives in their tombs.

The tomb of Francis I and Queen Claude of France takes a similar form, while celebrating the knight-king’s 1515 battle victory at Marignan near Milan, Italy. The battle preparations, crossing the Alps and combat are shown, with Francis I as a knight at the head of his army with an “F” monogram on his horse saddle.

The tomb of Catherine de Medici celebrates Catholic themes. Her husband, Henry II (r. 1547-1559), died after a tournament in Paris and she ruled through her three sons for many years. Her tomb was originally in a rotunda north of the abbey, but was later installed in the basilica. Some of the greatest Renaissance sculptors worked on the project. However, she didn’t like her corpse statue, which she thought was macabre and emaciated. She had a second one sculpted that shows her in a gentle sleep. It is in Saint Denis, while the first one is in the Louvre.

The tomb of Catherine de Medici and her husband Henry II is a masterpiece of Renaissance sculpture by some of the greatest artists of the era. Below, Catherine's clothing is carved in exquisite detail.

When the banner of Saint Denis later did not help the French win battles against the English, relations between the abbey and the kingdom grew more distant and the church declined in influence. It was looted repeatedly in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Before the revolution of 1789, the mediaeval and Renaissance rulers were buried under their sculpted monuments. The Bourbon rulers were buried in the central part of the crypt in plain lead coffins encased in wood.

The church was a prime target of the French Revolution because of its association with the monarchy. The medieval monastic buildings around it were demolished in 1792 and the monks dispersed. The church was desecrated and looted of its treasury and reliquaries. Liturgical furniture was melted down for its metallic value, although some items from Suger’s era were hidden and survived. The ancient rulers’ remains were removed in August 1793 as part of a revolutionary Festival of Reunion, and the Bourbon and Valois monarchs were removed to celebrate the execution of Marie Antoinette in October 1793. The job was outsourced to a contractor and workers who pried the coffins open with pickaxes and crowbars. They started with Henry IV, whose body was well preserved by natural mummification. Louis XV’s body, wrapped in linen, appeared to be in good condition but dissolved when it was lifted out. The bodies were thrown into mass graves in the Valois cemetery on the north side of the building. A monk who was a witness said most of the bodies were decaying and a foul-smelling black vapor was released from them. The workers tried to dispel the smell with vinegar and powder that they burned. The Old Testament kings on the church’s façade, assumed to be images of French kings and queens, were removed. More than 80 percent of the tombs and effigies were saved by the Commission of Monuments and archeaologist Alexandre Lenoir, who claimed them as works of art for his Musée des Monuments Français in 1798.

Empty coffins in the crypt of Saint Denis. The remains were removed during the French Revolution.

The lead roof of the building was removed by the Arms and Powders Commission to be used in weaponry for on-going wars, along with metal plates and tombs. The building almost was demolished to build a street through its site. It was used as a storehouse for wheat and flour, and there was talk of creating a market hall in its place.

After the revolution, Napoleon decided to restore the church and it returned to its role as a place of worship. When the Bourbons were restored to power, King Louis XVIII had the nearby cemetery searched and excavated for remains of the kings and other royal figures. The bones of 158 bodies were found, but it was not possible to associate them with specific royals so they were buried in an ossuary in the church. The reigning royal couple at the time of the revolution, Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette, had been guillotined in 1793 and their bodies, along with Louis’ sister Madame Élizabeth’s body, had been buried covered with quicklime in the churchyard of another Paris church, Madelaine. A search was made for their remains, but only a few bones believed to be the king’s and a clump of grayish matter containing a lady’s garter were found. With great pomp, the remains of the couple were transferred to Saint Denis along with the remains of Louis VII and Louise of Lorraine, the wife of Henry III. They are buried under slabs of black marble installed in 1975.

Statues of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette that are one of the prominent features of the church also were erected. Their child Louis XVII died in the custody of the revolutionaries. Nothing remained of him except a pebble-sized mummified heart, which was sealed into the wall of the church’s crypt in 2004. The restored King Louis XVIII was the last monarch buried in the basilica. He died in 1824 and was buried near the graves of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette.

A monument to Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette installed after the Bourbon monarches temporarily returned to power.

What remains of royalty at Saint Denis today is mostly the stone effigies and tombs. The church now contains the tombs of 42 kings, 63 queens, 63 princes and princesses and 10 other prominent servants of the court. Just three monarchs of France from the 10th century to 1789 are not buried at the church.

An early-18th century attempt to restore the church was not particularly successful, especially rebuilding of the north spire after lightning struck it in 1837. It collapsed in 1845. In 1846, the 19th century architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, who also restored Notre Dame Cathedral, launched a major restoration of Saint Denis. An excavation revealed earlier structures and Merovingian tombs.

A number of archeological excavations have been made in the area of the church. At the cemetery to the north, more than 40,000 graves on 40 levels of occupation starting with the 6th century have been discovered. Thousands of objects have been discovered in the excavations.

A model of the church and monastery as they once were, with the surrounding town of Saint Denis.

The square in front of the abbey was called the Panetiere, meaning a place where bread was sold twice a week, and a large market still is held there three times a week. The medieval buildings of the monastery were rebuilt in the 18th century and now are a school for girls whose parents or grandparents have received the Legion of Honor or National order of Merit. The buildings and cloister gardens were recently rebuilt.

The government is involved in a project to renovate the venerable old royal repository that will take more than a decade. The façade was restored from 2012 to 2015. The restoration is expected to include reconstruction of the long-gone north tower.

Check out these related items

Paris’s Oldest Church Restored

Paris' oldest church, Saint Germain des Prés, is emerging from layers of grime and soot as a meticulous restoration reveals its vibrant color.

The World Mourns Notre Dame

Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris, France's national cathedral, was badly damaged in a fire.

What is the Louvre?

The former palace, the world's largest museum, music video and fashion show venue, and global brand has never been more cool.

Scaffolding the World

Finding a historical site shrouded in scaffolding is disappointing, but it is a valuable tool for preserving the world's heritage.

Marie Antoinette and Barbie

Since she was guillotined in the French Revolution, Marie Antoinette has become one of the most popular icons worldwide.

Treasure Room and Two Palaces

In the French palace at Fontainebleau is a treasure room of dazzling artifacts taken by the French army from a palace in Beijing.