The Rosetta Stone

Photos by Forrest Anderson

The Rosetta Stone, the most visited object at the British Museum in London, is the focus of a thrilling tale - the clash of empires ancient and modern, the discovery of the stone and the cracking of its code.

The stone attracts crowds of visitors to peer at it through its glass case in the center of the Egyptian gallery, while scholars debate controversaries surrounding it and the enormous field of scholarly studies that it opened the way for. Not bad for an artifact that originally was a mass-produced propaganda plaque and eventually landed in a rubble pile.

The Rosetta Stone is among the world’s greatest historical treasures, right up there with the Parthenon Marbles, the Easter Island statues and King Tut’s tomb. Why? Because the stone by happenstance became the key to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphics, which are considered the ancestor of written languages of Europe, the Indian subcontinent and parts of East Asia.

Clashing Empires

The Rosetta Stone from its beginning to the present day has been tied up with the history of competing European and northern African empires.

Egypt from whence the stone came is one of the world’s oldest civilizations, with the political unification of the country occurring in 3150 B.C. It was repeatedly conquered in ancient times and incorporated into the dominent empire of the day. The Achaemenid Empire conquered Egypt in the sixth century BC. Greek ruler Alexander the Great toppled the Achaemenids in 332 BC and established a short-lived empire that gave rise to the Hellenistic Ptolemaic Kingdom during which Egypt was controlled by Greek rulers under Greek law and with Greek as the official government language until Rome annexed Egypt as a province in 30 BC.

This was the backdrop for the story of Ptolemy V (210 BC-180 BC), who came to the throne at age six after his parents were killed. He had a turbulent childhood with a series of incompetent regents, while the Ptolemies lost many of their territories to other nations or in an internal revolt against Greek rule. Ptolemy V steadily reconquered the south of Egypt to bring all of Upper Egypt under his control. Ptolemy V needed allies to help strengthen his power and stabilize the fractious kingdom, and courted the long-standing Egyptian priesthood as one of them.

The priests’ favor was essential for a king to be effective because priests were the highest religious authorities.

Sarcophagus of Egyptian priest in Memphis, British Museum, London. From a much earlier time than the Rosetta Stone, the sarcophagus attests to the ancient and important role of priests in Egypt.

The decree on the Rosetta Stone was passed by a synod of priests that met at Memphis on March 27, 196 BC, the day after Ptolemy V was crowned as an adult. The decree established the ruler’s divine cult. (The demotic text on the stone also has another date, Nov. 26, 197 B.C., which was the official anniversary of Ptolemy’s coronation. It is unknown why the two dates are different.) The point of the decree was to re-establish Ptolemaic rule over Egypt following the revolt.

Temples created stelae of the Rosetta Stone type which are unique to Ptolemaic Egypt. This way of honoring kings was a feature of Greek cities, so the custom probably was Greek. Rather than honoring himself on a stele, the king had a representative group of his subjects do so.

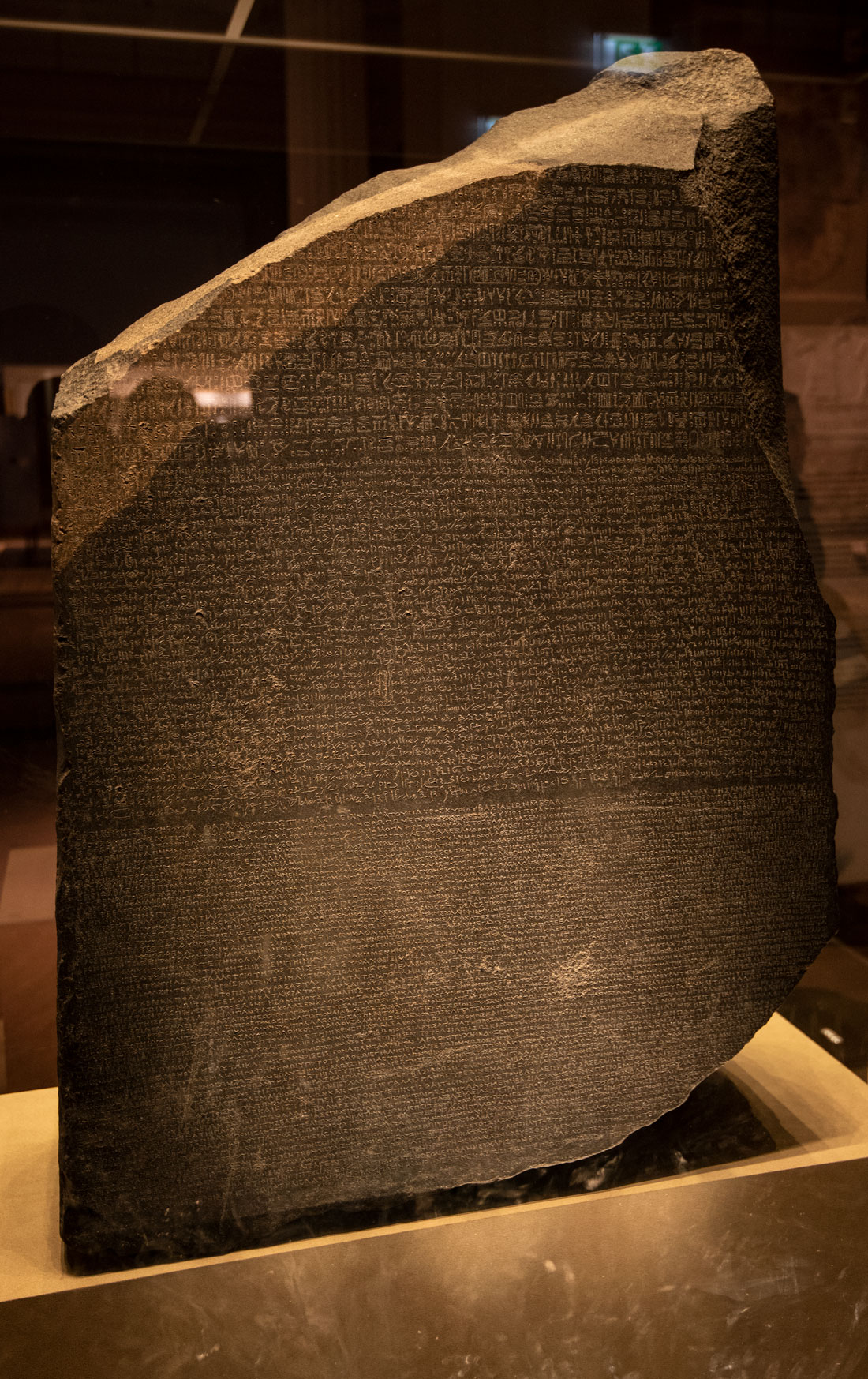

A copy of the decree, according to the inscription on the stone, was to be placed in every temple, inscribed in "the language of the gods," which was Egyptian hieroglyphs; the "language of documents" or demotic Egyptian; and the language of the Greeks as it was used by the government.

The use of the different languages was intended to show the connection between the Egyptian priesthood and general populace and the government. However, it also was an indication of the divisiveness of the time.The court and government used Greek, the priests read and wrote in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics and the people spoke Egyptian, which was written in demotic script. The Rosetta Stone reflects the confluence of a historic moment when all three languages were used and a compromise between Greek-dominated Ptolemy V and the priests who represent ancient Egyptian culture.

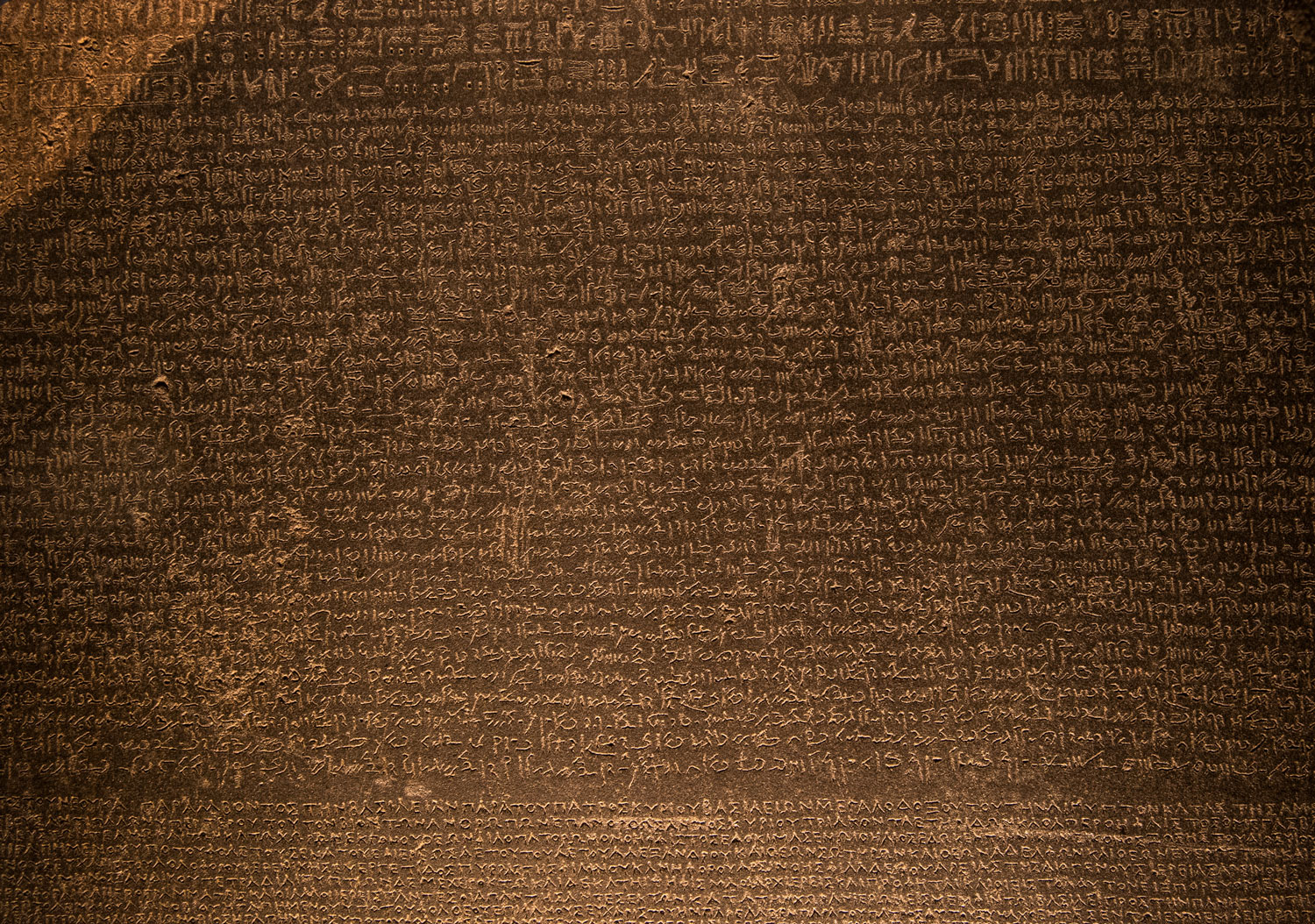

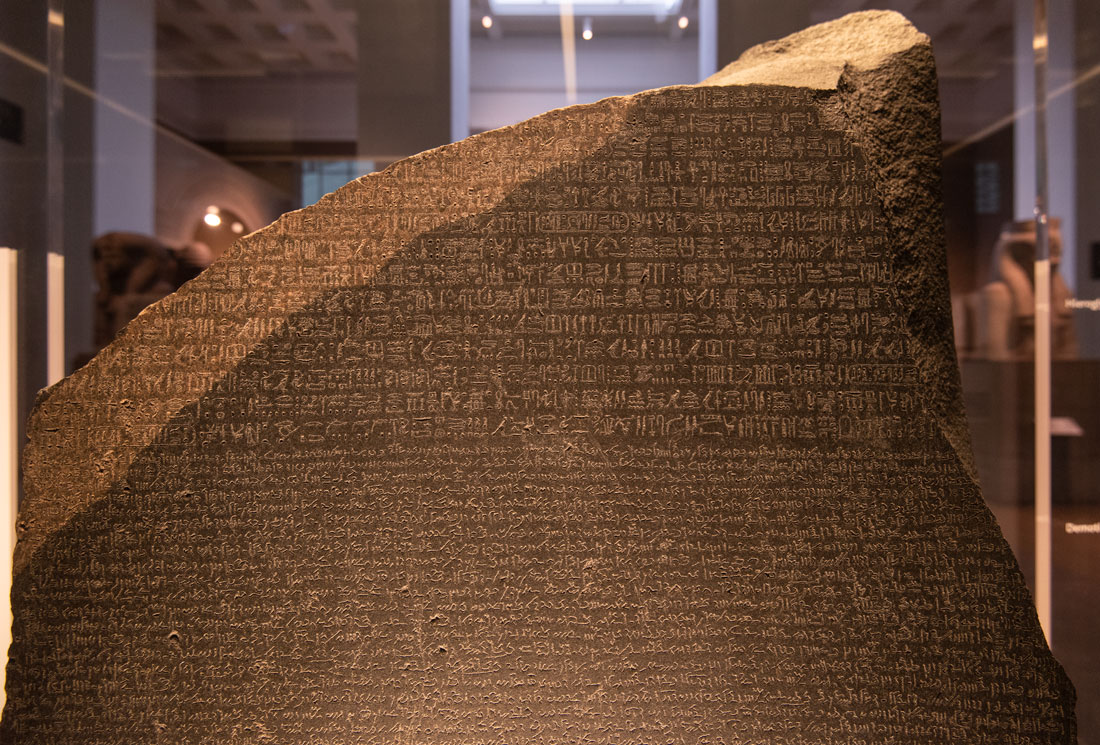

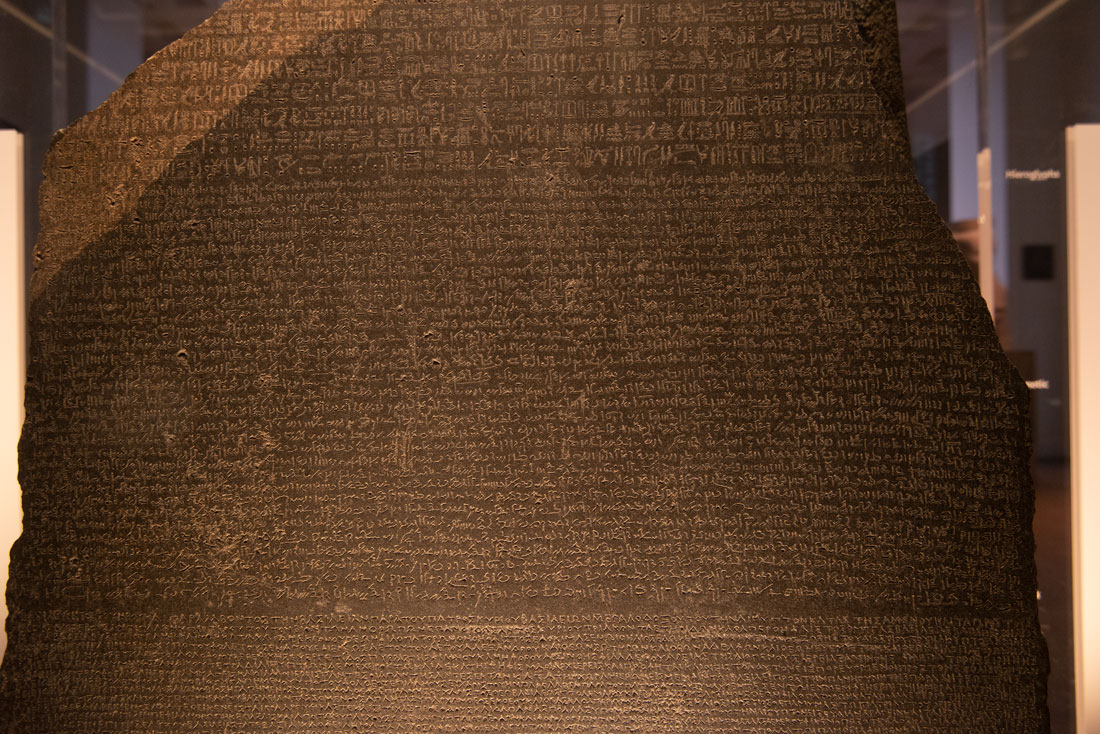

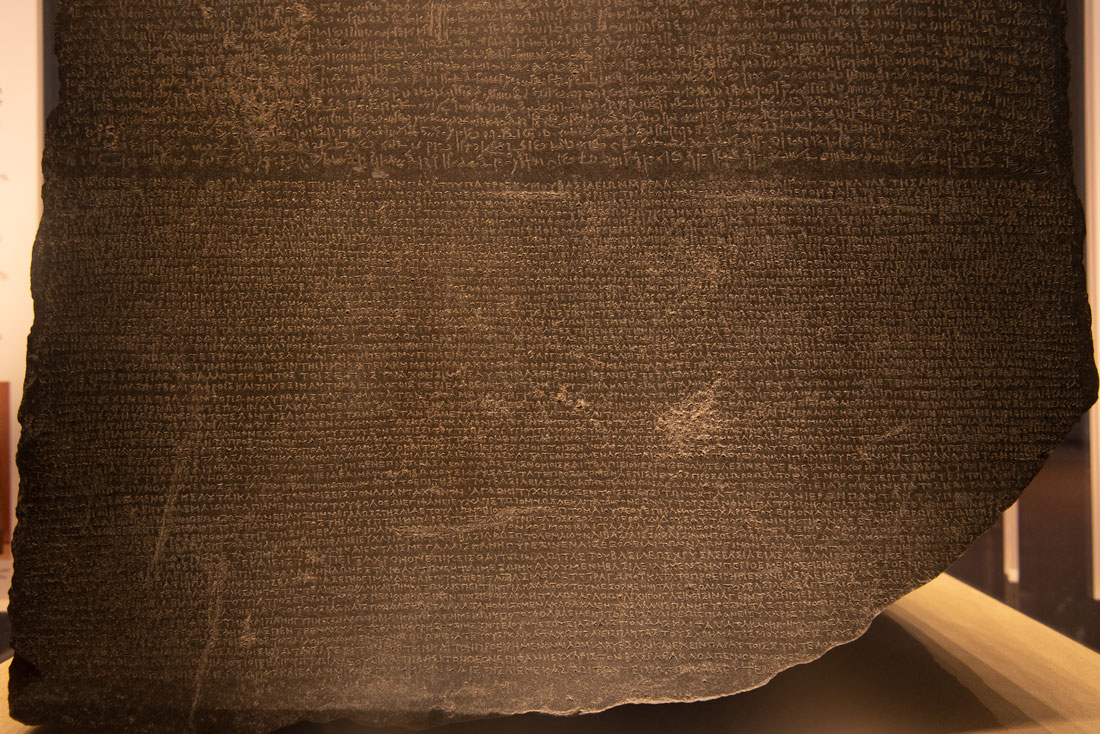

The top part of the stone is broken off. What survives shows Egyptian hieroglyphics at the top with Egyptian demotic, a cursive script, underneath it. The bottom text is in Greek, as shown below.

The decree talks about Ptolemy V’s victory over the Egyptians who were rebelling against Greek rule, asserting Ptolemy’s authority while giving concessions to the priests. The text lists some of the king’s noble deeds, such as giving gifts to the temples and granting them tax reductions, damming the Nile during flooding to help farmers, freeing prisoners, agreeing not to make priests serve in the navy, and other concessions.

In return, the council of priests pledged to bolster Ptolemy V’s royal cult by building new statues, decorating his shrine and celebrating his birthday and anniversaries of his accession to the throne.

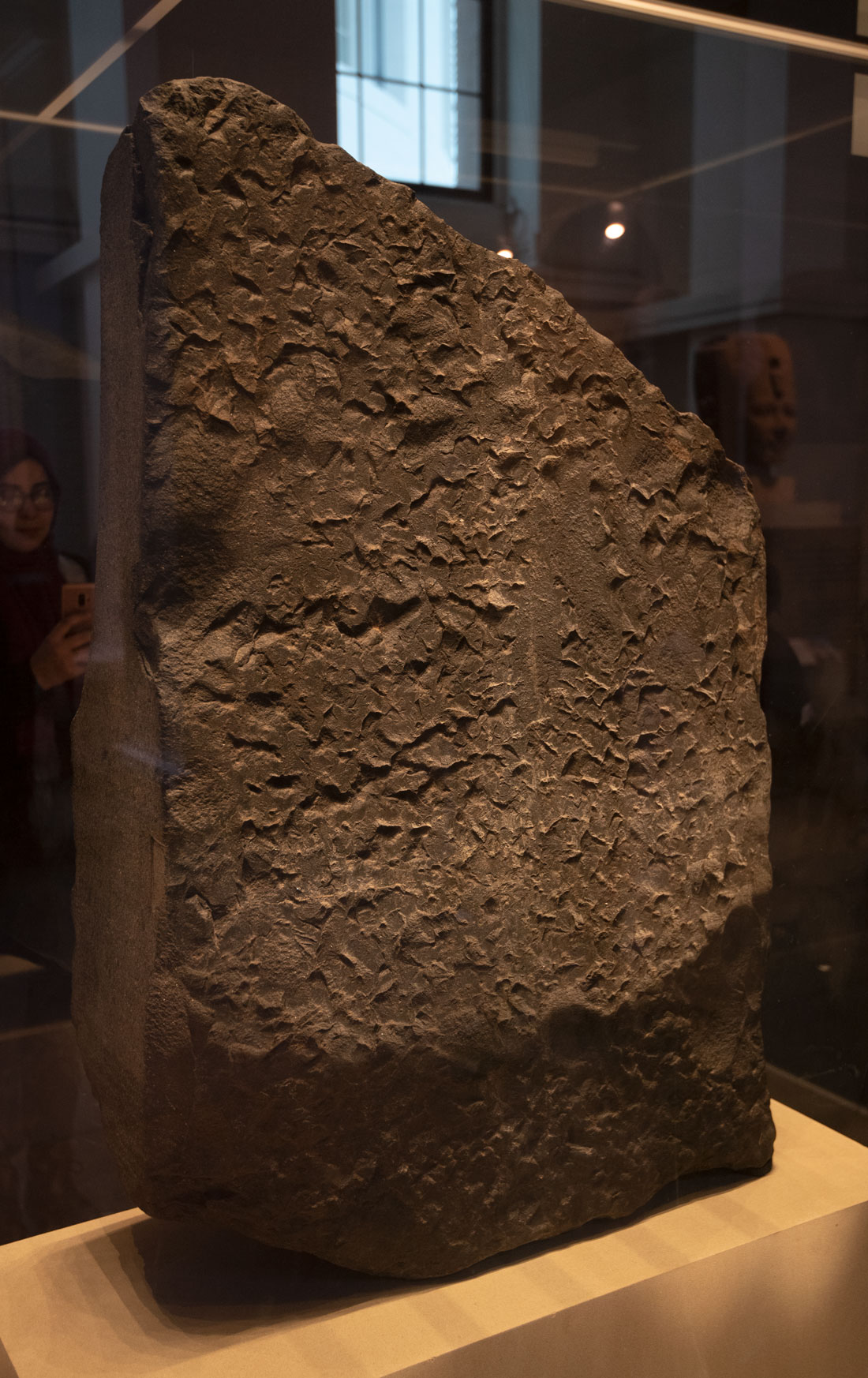

The stone has one smooth side with the text inscribed on it and a rough back that apparently was not visible when it was installed in a temple. It is believed to have been installed in a temple in Sais, not far from the place that Europeans later called Rosetta and which is today called Rashid.

The rough back side of the Rosetta Stone.

Predictably, the mass-produced stelaes eventually went out of style after Ptolemy passed away in 180 BC, supposedly poisoned by courtiers disgruntled over his policies. His reign marked the collapse of Ptolemaic power in the Mediterranean, leading to the Roman conquest of the eastern Mediterranean.

Christianity spread in Egypt during the Roman era. In 392, Roman Emperor Theodicius declared Christianity as the empire’s official religion and ordered non-Christian temples destroyed. This probably included the temple in which the Rosetta Stone was placed.

Along with the temples went Egyptian hieroglyphics, the language used for inscriptions on monuments at the temples. By the 5th century, the knowledge of hieroglyphs was lost.

The temples were used as quarries for new construction, and the Rosetta Stone was repurposed. In the 1400s, it was placed in the foundation of a fortress built by the Mamluk dynasty to defend a branch of the Nile at Rosetta. The Mamluks originally were a slave corps of a Muslim army that eventually rose to rule Egypt and Syria from 1250 to 1517. Their descendents continued to be important in Egypt even after they were defeated when the Ottoman empire conquered Egypt in 1517.

The Ottomans occupied Egypt until 1798, when another clash of empires was in full swing.

Egypt was in a strategic Mediterranean location for both Britain and France, and both rising empires were vying for control of it. French General Napoleon Bonaparte’s army invaded Egypt in July 1798 and rapidly defeated the Ottomans. Napoleon’s army included 167 scholars tasked with studying the history, culture and natural environment of Egypt and collecting important artifacts and specimens.

A year later, French troops and local workers near the village of Rosetta were strengthening the defenses of the fort there, when they saw in a rubble pile a slab with inscriptions on one side. Lt. Pierre-François Bouchard immediately informed French General Jacques-François Menou, who happened to be at Rosetta, and the find was announced to the scholars in Cairo in a report. The report suggested that the three inscriptions might be the same text. Bouchard sent the stone for scholars to examine The stone was named La Pierre de Rosette, or in English the Rosetta Stone.

French control of the stone was short-lived. The next month, the British destroyed the French fleet at the Battle of the Nile. Lord Elgin, the British minister to Constantinople and the man who was famous for collecting the Parthenon marbles and shipping them off to Britain, got wind of the stone and made sure that his principal agent was with the British expedition to secure for Britain the stone and other artifacts assembled by the French. The British landed near Alexandria, Egypt, in March 1801. The French troops marched north to meet the British, taking the stone and many other Egyptian antiquities. The French were defeated, and retreated to Alexandria where they were besieged.

The French refused to hand over the artifacts, specimens, and the notes, plans and drawings their scholars had made, and the British refused to end the siege until they did so.

Elgin’s agent brokered the adding of a clause to the surrender treaty claiming for Britain the Rosetta Stone and other antiquities found by the French scholars. When Alexandria fell to the British, the stone was hidden in a warehouse with General Menou’s baggage, but the agent tracked the stone down and seized it along with other artifacts hidden around the city. The stone was sent to Britain in a captured frigate, arriving in 1802. It was turned over to the British Museum where it has remained ever since except for a brief sojourn in an underground railway station during bombing in World War I.

Deciphering the Stone

Thus ensued a 20-year intense race to decipher the stone’s inscription.

The first step was to to recognize that the top text on the stone was in Egyptian hieroglyphics, the middle in ancient Egyptian demotic and the bottom in Greek. In 1800, French scholar Jean-Joseph Marcel recognized that the middle text was demotic, not Syriac as originally was thought.

By 1802, scholars had produced the first English translation of the Greek text, with a French and Latin one following in 1803. A suggested reconstruction was made of a portion of the Greek text that was missing because the stele’s lower right corner was broken off.

However, no one was familiar with how Greek was used as a government language in Ptolemaic Egypt, as later large-scale discoveries of Greek papyri had not yet occurred. The translators struggled with grasping the historical context of the text and its administrative and religious terms.

When the stone was discovered, Swedish scholar Johan David Åkerblad was working on a little-known script of which some examples had recently been found in Egypt. He called it cursive Coptic because he thought it was used to record a form of the Coptic language which is the direct descendant of ancient Egyptian, although it wasn’t very much like later Coptic script.

French Orientalist Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy realized that the middle text on the stone was in the same script as Akerblad’s other samples. By 1802, Silvestre de Sacy had identified five names in the text while Åkerblad published an alphabet of 29 letters, more than half of which were correct, that he had identified from Greek names in the demotic text. Since then, the remaining characters in the demotic text have been identified. It is now known that they included both ideographic and other symbols in addition to phonetic ones.

In 1811, prompted by discussions with a Chinese student about Chinese characters, Silvestre de Sacy considered an earlier suggestion that foreign names in Egyptian hieroglyphs might be written phonetically as the Chinese did. He suggested in a 1814 letter to Thomas Young, foreign secretary of the Royal Society of London, that Young might look for cartouches (oval frames placed around names in hieroglyphics) that might contain Greek names and try to identify phonetic characters in them.

This suggestion paved the way for the final decipherment of the stone. In the hieroglyphic text, Young discovered the phonetic characters "p t o l m e s" which were used to write the Greek name "Ptolemaios". He noticed that these characters resembled equivalent ones in the demotic script. He went on to recognize some 80 similarities between the hieroglyphic and demotic texts on the stone. Young concluded that demotic was only partly phonetic and also had ideographic characters derived from hieroglyphics.

French scholar Jean-François Champollion saw copies of hieroglyphic and Greek inscriptions of the Philae obelisk in 1822 on which British scholar William John Bankes had tentatively noted the names "Ptolemaios" and "Kleopatra" in both languages. From this, Champollion identified the phonetic characters k l e o p a t r a. On the basis of this and foreign names on the Rosetta Stone, he constructed an alphabet of phonetic hieroglyphic characters. He wrote a famous "Lettre à M. Dacier" to Bon-Joseph Dacier, secretary of the Académie, detailing his discovery. Champollion noted that similar phonetic characters occured in both Greek and Egyptian names.

He confirmed this hypothesis in 1823, when he identified the names of pharaohs Ramses and Thutmose written in cartouches at Abu Simbel, Egypt. Champollion then drew on many other texts to develop an Ancient Egyptian grammar and hieroglyphic dictionary that were published after his 1832 death.

Work on the stone now focused on gaining a fuller understanding of the texts and their contexts by comparing the three versions with one another. In 1824, scholar Antoine-Jean Letronne had promised to prepare for Champollion a new literal translation of the Greek text. His analysis was found in the papers of a former student of Champollion’s after the student died in 1838. The discovery was a scandal, because it showed hat the student’s own 1837 publication about the stone was plagiarized. Letronne finished a commentary on the Greek text and a new French translation of it in 1841.

German scholars created revised Latin translations based on the demotic and hieroglyphic texts in the early 1850s and American scholars did the first English translation of those texts in 1858. By the late 1860s, there was a dictionary of Egyptian hieroglyphics, which scholars have refined up to the present.

Development of Rosetta Stone-related Studies

Three other fragmentary copies of the stone’s decree were later discovered along with several similar bilingual or trilingual inscriptions. The hieroglyphic texts of these inscriptions were relatively intact and have been used to refine the reconstruction of hieroglyphics that were probably on lost portions of the Rosetta Stone. Similar inscriptions in two or three languages also have been found, including three Ptolemaic ones carved slightly earlier than the Rosetta Stone - the Decree of Alexandria in 243 BC, the Decree of Canopus in 238 BC, and the Memphis decree of Ptolemy IV in about 218 BC.

Sometime after the stone arrived in London, white chalk was scraped over the inscriptions on it to make them more legible. The rest of the surface was covered with carnauba wax to protect it from people’s fingers. The stone turned dark, leading to the erroneous assumption that it was black basalt.

The stone was cleaned in 1999 and the chalk and wax removed, revealing the stone’s original dark gray crystalline structure and a pink vein across the top left corner. This launched a study of rock samples in the British Museum that had been collected from Egyptian quarries. The Rosetta Stone closely resembled samples from a granodiorite quarry at a small mountain called Gabal Tingar on the west bank of the Nile. The pink vein was typical of the granodiorite. Granodiorite is a course-grained rock similar to granite.

The Rosetta Stone is 3 feet 8 inches high, 2 feet 5.8 inches wide and 11 inches thick. It weighs 1,680 pounds. The stone is only a fragment of a much larger stele and no further fragments have been found, so none of the three texts on it is complete. Only the final 14 lines of the hieroglyphic text exist and they are broken on both sides.The demotic text has 32 lines, 14 of which are slightly damaged on the right. The bottom Greek text has 54 lines, with 27 in full and the others fragmentary.

Scholars believe that based on other comparable stelae, the Rosetta Stone probably had another foot of text at the top and above it a carving of the king being presented to the gods, so it probably was close to five feet tall with a rounded top.

Because of minor differences between the texts, there is no one definitive English translation of the decree on the Rosetta Stone. Scholars have never agreed on which text is the original decree from which the other two were translated.

New inscriptions painted in white on the left and right edges of the slab state that it was "Captured in Egypt by the British Army in 1801" and "Presented by King George III". Small portions of its sides also were shaved off to fit it securely into a metal cradle for display.

The stone and other Egyptian objects were too heavy for the floors of Montagu House, the original British Museum building, so they were transferred to a new extension added to the building. The Rosetta Stone was transferred to the sculpture gallery in 1834 after Montagu House was replaced by the current British Museum building.

By 1847, the stone was placed in a protective frame so visitors couldn’t touch it. Since 2004, the stone has been on display in a special case in the center of the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery. A replica of the stone is at the King's Library of the British Museum with no case so that people can touch it.

An image of the Rosetta Stone was the museum's best selling postcard for decades. The museum shops sell a wide variety of Rosetta-themed merchandise.

Except during World War I, the stone has left the museum only once – to be displayed at the Louvre in Paris in 1972 for the 150th anniversary of Champollion’s famous 1822 letter. A giant copy of the Rosetta Stone is at the birthplace of Champollion in Figeac, France.

In the 1970s, French viewers of the stone complained that Champollion’s portrait was smaller than one of Young on an adjacent information panel, and English visitors complained that the opposite was true. The portraits in fact were the same size.

In the early 2000s, Egypt made repeated appeals for the stone to be returned to Egypt, calling it “the icon of our Egyptian identity.” The British Museum in 2005 presented Egypt with a full-sized fibreglass replica of the stele that was displayed in the renovated Rashid National Museum in Rashid, but has no plans to return the stone.

More than 30 national museums, including the British Museum, Louvre, Pergamon Museum in Berlin and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in 2002 issued a joint statement declaring that “objects acquired in earlier times must be viewed in the light of different sensitivities and values reflective of that earlier era" and that "museums serve not just the citizens of one nation but the people of every nation."

Egyptian Hieroglyphic Studies

It has become common to call ancient bilingual or trilingual inscriptions and documents Rosetta stones because they contribute to the deciphering of ancient written scripts. Among other Rosetta stones are bilingual Greek-Brahmi coins of the Greco-Bactrian king Agathocles that helped unlock the Brahmi script and the Behistun inscription on a cliff in Iran that enabled the decipherment of cuneiform script in Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian.

The term Rosetta stone also has been used to denote the first clue in the process of decrypting any encoded information in fields such as chemistry, genetics, biology, astrophysics and medicine.

The European Space Agency's Rosetta spacecraft was launched to study the comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko in hopes that determining its composition would advance understanding of the solar system’s origins. A program billed as a "lightweight dynamic translator" that enables applications created for PowerPC processors to run on Apple systems was named "Rosetta". Rosetta@home is a distributed computing project for predicting protein structures from amino acid sequences. The name Rosetta Stone is used for language learning software.

The Rosetta Project brings together language specialists and native speakers to develop a meaningful survey and long-term archive of 1,500 languages in both physical and digital form.

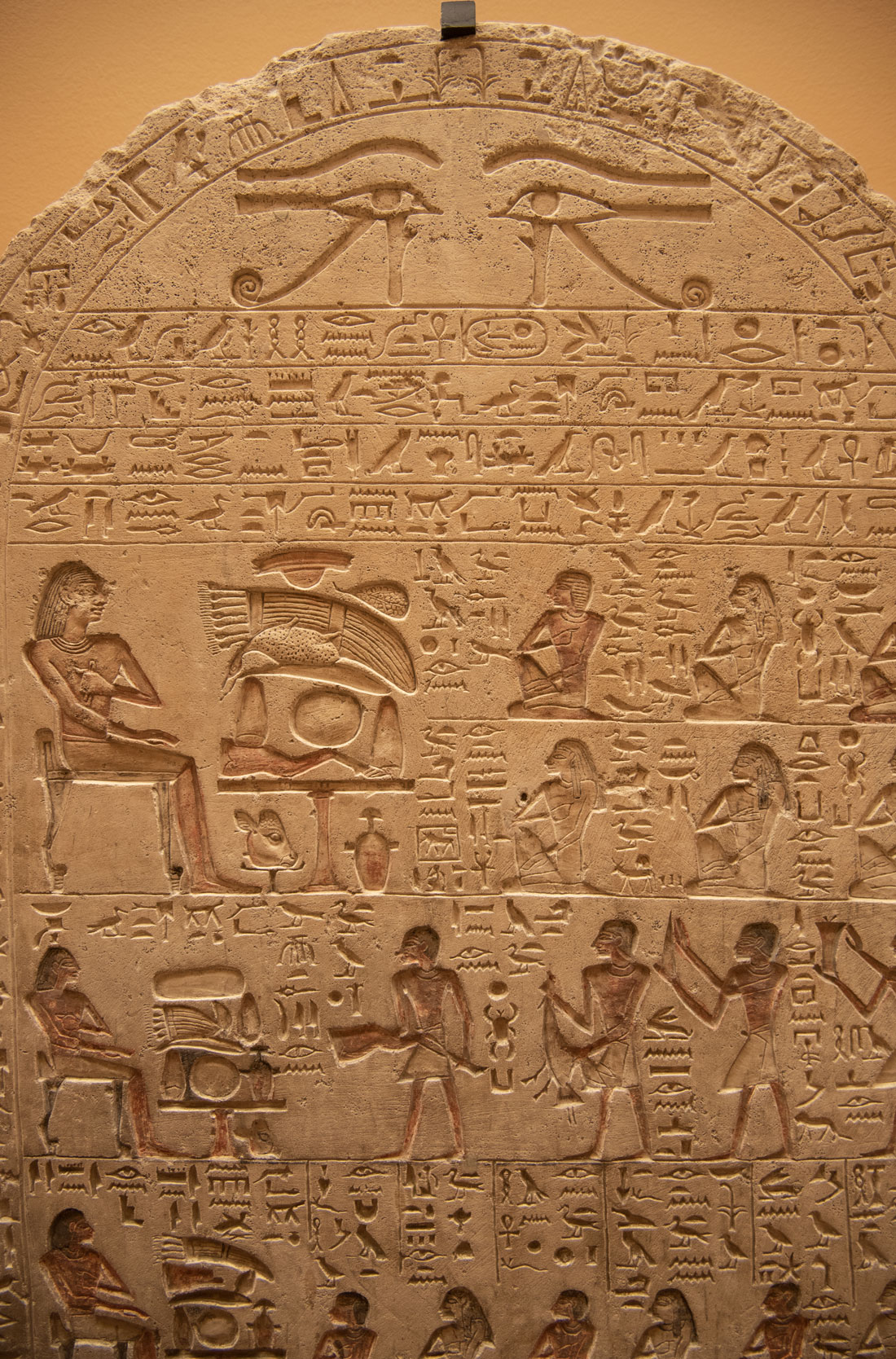

Knowledge of Egyptian hieroglyphics has been important in understanding ancient Egypt because there are few Egyptian works of art that don’t include hieroglyphic writing.

It was common for Egyptian monuments to be inscribed with a combination of human figures and hieroglyphic writing, as shown in this stele in the Louvre, Paris.

Hieroglyphs may have emerged from symbols on items such as pottery and clay labels from 4000 B.C. Some scholars think Egyptian hieroglyphics were influenced by Sumerian script from Mesopotamia, while others dispute that. Mesopotamia had used signs in tokens as far back as about 8000 BC.

The first full sentence written in mature hieroglyphs so far discovered was on a seal impression in a tomb dating from about 2800 BC. The number of hieroglyphs grew until by the Greco-Roman period, there were more than 5,000. Hieroglyphics were extremely important to Egyptian society as were scribes.

Statue of an Egyptian writing, the Louvre, Paris.

Egyptian hieroglyphs consist of three kinds of glyphs - phonetic, which function like an alphabet; logographs, which represent entire words or roots of words; and determinatives, which narrow down the meaning of logographic or phonetic words, especially homophones. Champollion described hieroglyphics after he figured them out as “a complex system, writing figurative, symbolic, and phonetic all at once, in the same text, the same phrase, I would almost say in the same word.”

The language had both symbols representing syllables and alphabetic ones. It also had a cursive form used for religious literature on papyrus or wood. Later cursive script used for writing on papyrus, called hieretic script, and its derivative, demotic script, developed from Egyptian hieroglyphics. Egyptian hieroglyphics were the ancestor of the Proto-Sinaitic script that later evolved into the Phoenician alphabet. Its descendants were the Greek and Aramaic scripts. Egyptian hieroglyphics thus were the ancestor of the majority of scripts in modern use - Latin and Cyrillic scripts, Arabic script and possibly Brahmic scripts used throughout the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia and parts of East Asia including Japan.

One controversy surrounding Egyptian hieroglyphics is the relationship between them and ancient Chinese characters. The two scripts have similarities, but also significant differences, and the subject is touchy for Chinese nationalists who bristle at the idea that Chinese characters and other ancient Chinese achievements could have been derived from western civilizations.

Hieroglyphs were called the writing of the gods because they were used on religious monuments. The Nag Hammadi texts, which were written in Sahidic Coptic, call the hieroglyphs "writings of the magicians, soothsayers.”

Hieroglyphics represent real or abstract elements that are generally recognizable in form, but the same sign can be interpreted in different ways depending on the context. Hieroglyphics don’t indicate vowels, spaces or punctuation. They are in rows arranged in either horizontal or vertical lines. Ordinarily, they are read from right to left, but if the human and animal ones face toward the left, they are read left to right.

Twenty-four symbols stood for single consonants, much like English letters, but the Egyptians never simplified hieroglyphics into a true alphabet. There were glyphs representing a specific sequence of two or three consonants, consonants and vowels, or vowel combinations. Some signs are contractions, such as a hand holding a scepter to convey the meaning “to direct.” Doubling of a sign meant two. Tripling meant plural.

Only a half dozen demotic glyphs are still used, when writing Coptic. However, hieroglyphic fonts have now been standardized and are supported by modern computers.

Since hieroglyphics were deciphered, scholars have focused primarily on the content of ancient Egyptian texts. We know that the Egyptians had a wide literature, were skilled astronomers, mathematicians who understood the principles of geometry, had books on medical science, and were superb architects. They worshipped more than 2,000 gods and goddesses, were great philosophers, had a postal system, had historians who recorded important events, and excelled in agriculture, irrigation, navigation, trade, commerce, metal working, ceramics, and efficient government administration.

Many of these accomplishments were passed on to later civilizations that achieved greatness in their own right.

More photos of the British Museum

More photos of the Louvre

Check out these related items

Ancient Silk Road Meets High Tech

The International Dunhuang Project digitizes old documents, caves and artifacts to enable global study of Central Asian history.

Britain and Greece’s Parthenon Dispute

What are the chances that two men from one family set off international disputes by carting off treasures from Greece and China?

China’s Stone Scriptures

Thousands of Buddhist scriptures carved in stone and buried for centuries are among China's greatest cultural treasures.

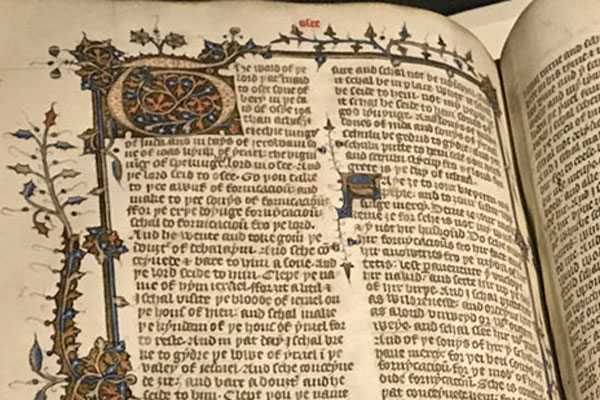

Translating the Bible

Millions of Christians will turn to the Bible this week to read the Christmas story in hundreds of languages.

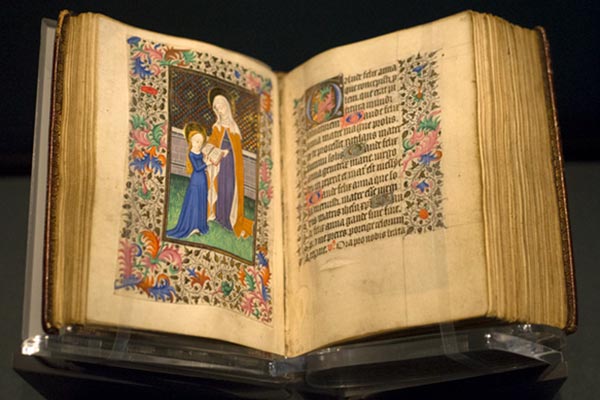

Illuminated Manuscripts

Illuminated medieval manuscripts preserved culture and religious beliefs and set a foundation for book design and art styles.

What is the Louvre?

The former palace, the world's largest museum, music video and fashion show venue, and global brand has never been more cool.