Translating the Bible

Millions of Christians will pull the Bible from their bookshelves this week and gather with their families to read the Christmas story. This tradition, which will be carried out in hundreds of languages, owes its origins to a vigorous two-millennia-old tradition of Biblical translation.

I was fortunate to have the opportunity to learn foreign languages at a young age. The caveat is that once you learn a language, you use it or lose it. That's a problem in a pandemic year when travel is out. Part of my strategy to deal with this has been to read a Spanish Bible for a few minutes daily. That’s how I bumped into the issue of tuberoses.

In English, the Christian New Testament describes a woman who anoints Jesus Christ’s feet with a costly ointment in an alabaster box. In Spanish, the woman anoints his feet with tuberose.

Tuberose? The lily-like Mexican flower? These question sent me down the long, winding rabbit hole of biblical translations. Tuberose, which originated among the Aztecs in Mexico, was unknown in the Holy Land at the time of Christ. It didn’t make its way to the Old World until after the Spanish conquistadors took it back with them to Europe after the early 1500s. Valued for its intense scent, the tuberose is now grown worldwide for use in bouquets and perfumes. It has been a symbol of purity at least since the Victorian era.

The translator of the Spanish New Testament that I was reading apparently considered the meaning associated with the flower more important than whether it actually was present at the biblical event. In Mexican Spanish, the flower is sometimes called the “vara de San José,” or “St. Joseph’s staff.”

Herein lies the basic dilemma in biblical translation – should a translation be word-for-word literal or should it emphasize a meaning that will resonate with readers of the translated text?

This is a global question, because almost a third of the world’s population identifies as Christian. Some portion of the Bible has been translated into more than 3,300 languages, with the full Bible in 700 and the New Testament in 1,500. English translation alone has continued for more than a millennium and includes many versions of the Bible.

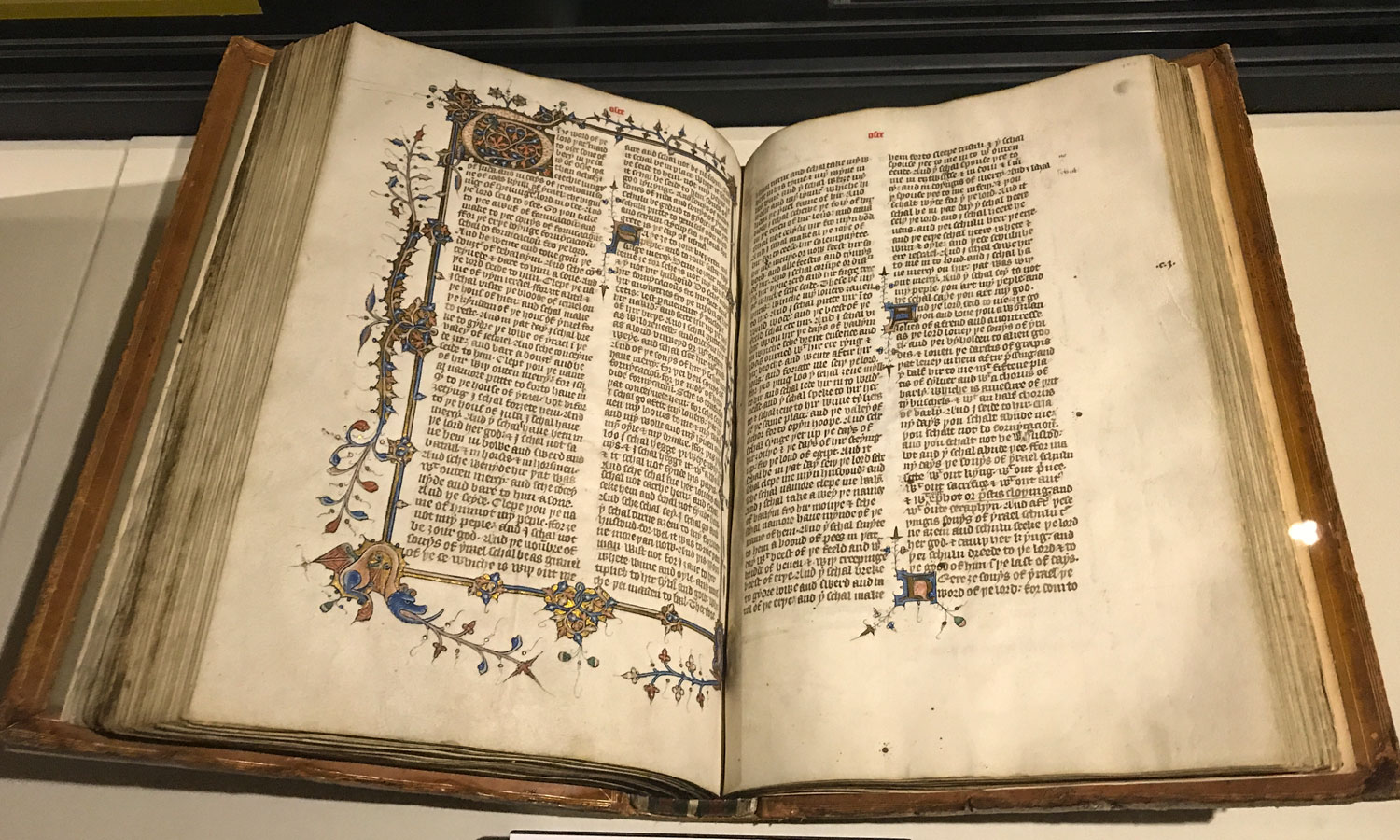

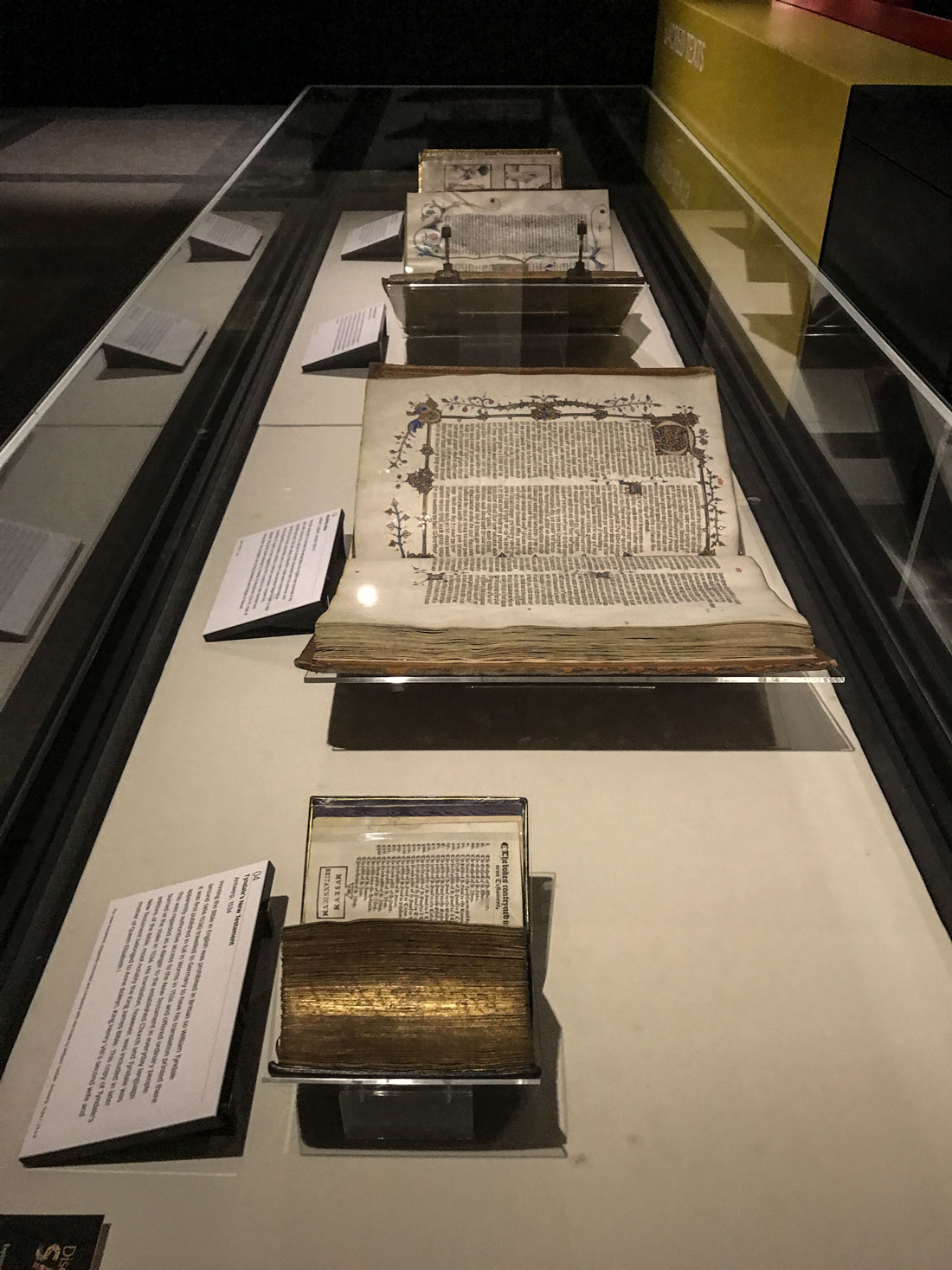

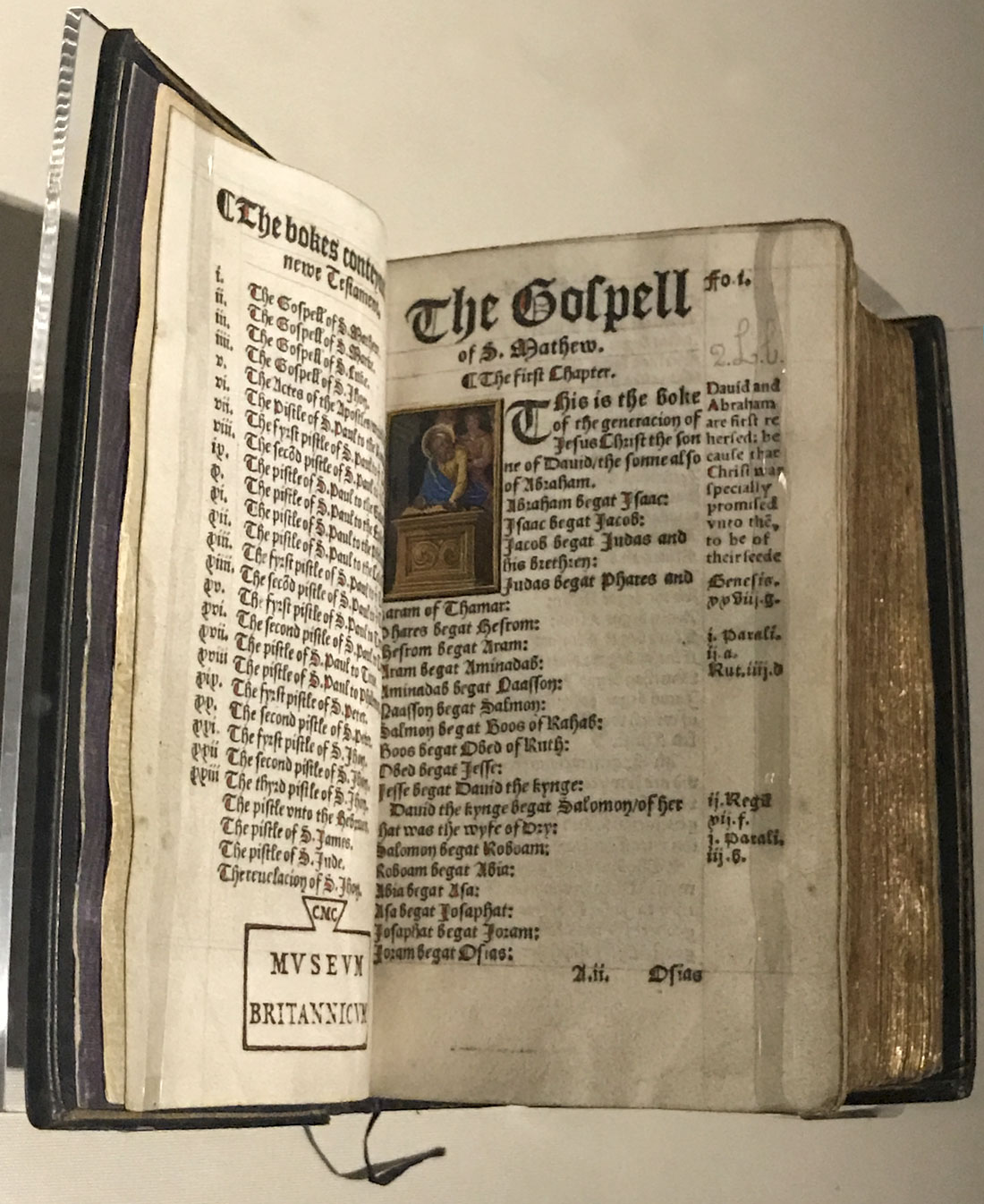

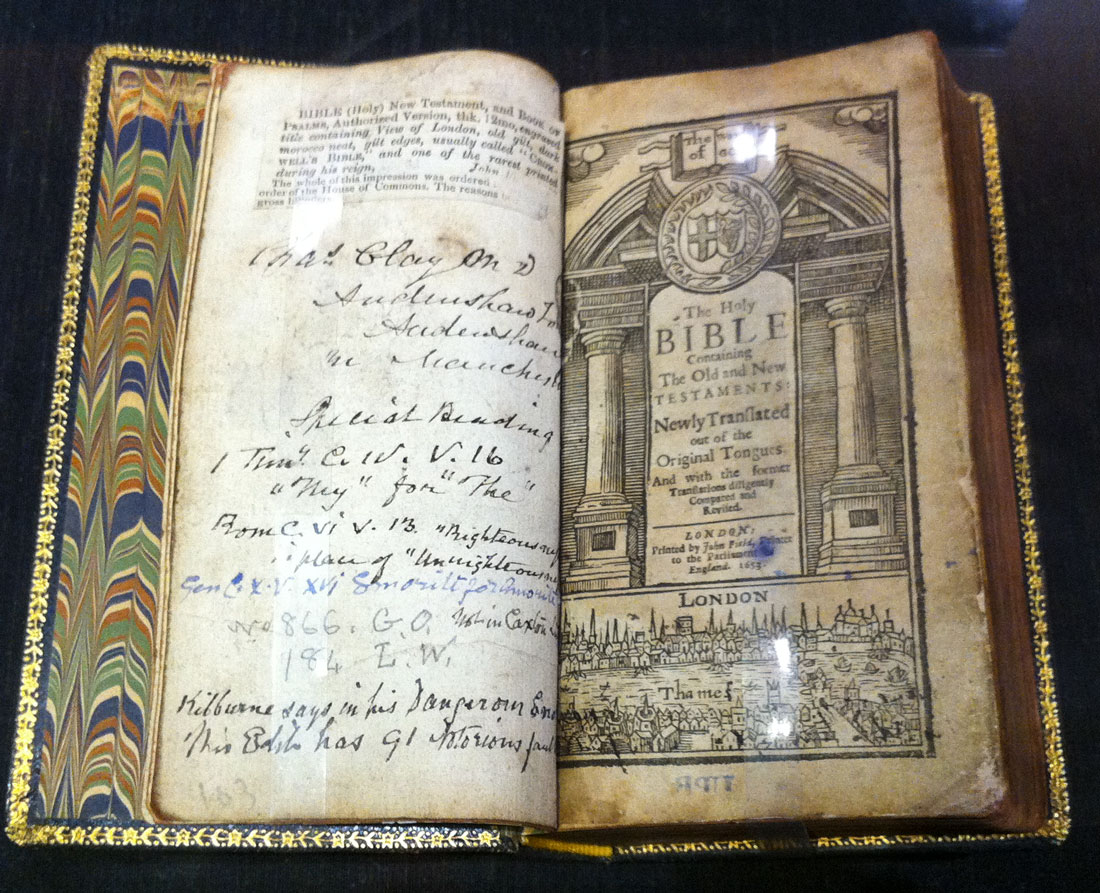

Famous Bibles at the British Library in London. The two closest are the Wycliffe Bible and the Tyndale Bible.

To understand Biblical translation, we need to start with the original languages of the Bible - Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek. The Hebrew Bible from which comes the Old Testament was mostly written in Hebrew, with portions in Aramaic. During the Jews' Babylonian captivity in the 6th century BC, Aramaic became the lingua franca and most Jews lost the ability to speak Hebrew. The Torah was translated into Aramaic, and the Aramaic versions survived after the original Hebrew scrolls were lost.

By the 3rd century BC, Greek had become the dominant lingua franca with Alexandria as the center of Hellenistic Judaism. A Greek version of the Hebrew scriptures was translated by 132 BC. Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the Egyptian pharaoh and son of a general of Alexander the Great, is credited with being the patron of an effort to gather 72 Jewish scholars for the translation. The unlikely legend later arose that 70 scholars separately translated the book and arrived at identical translations, which supposedly was proof of its accuracy and gave the project its name, the Septuagint. As Christianity spread in the Greek-speaking world, Christians also adopted the Septuagint as the source of their Old Testament.

Sometime before 240, the theologian/scholar Origen produced an edition of the Hebrew Old Testament called the Hexapla that placed six Greek and Hebrew versions of it side by side for comparison purposes. This book had an important influence on other important Old Testament manuscripts.

By 350, the Christian church had generally agreed on what texts were part of the biblical canon, although the book of Revelation was not accepted until 367.

Jewish scholars attempted from the 6th-10th centuries to compare the text of all known biblical manuscripts and created a standardized text. This produced a series of texts that are similar to each other known as the Mazoretic Texts. One of their main contributions was to introduce vowel sounds, as previous manuscripts had included only consonants. This sometimes required interpretation since some words differ only in their vowels. There are no complete surviving manuscripts of the Hebrew texts upon which the Septuagint was based, but many scholars believe that they represent a different tradition than that which was the basis for the Masoretic texts. Translations of the Christian canon tend to be based on the Hebrew Old Testament, although some denominations prefer the Septuagint.

The New Testament was written in a form of Greek that was the lingua Franca of much of the Mediterranean region and Middle East at the time of Christ and for centuries thereafter. It is still the liturgical language of the Greek Orthodox Church. There are three main textual traditions of the Greek New Testament – Alexandrian, Byzantine, and Western. The differences in the manuscripts from these traditions are mostly minor, although there are a few major ones.

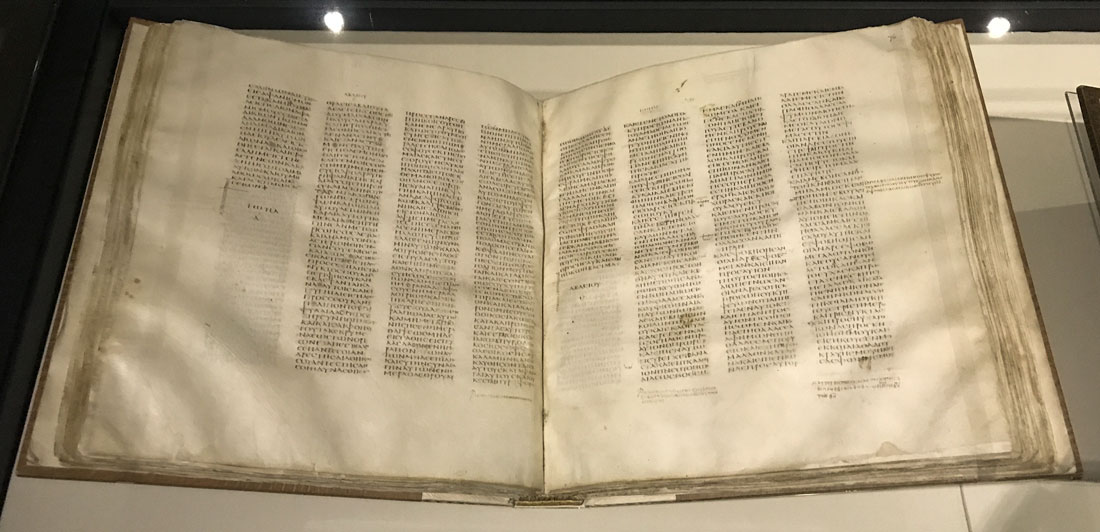

The 4th century Codex Sinaiticus, the earliest manuscript that contains the entire Bible in Greek. British Library.

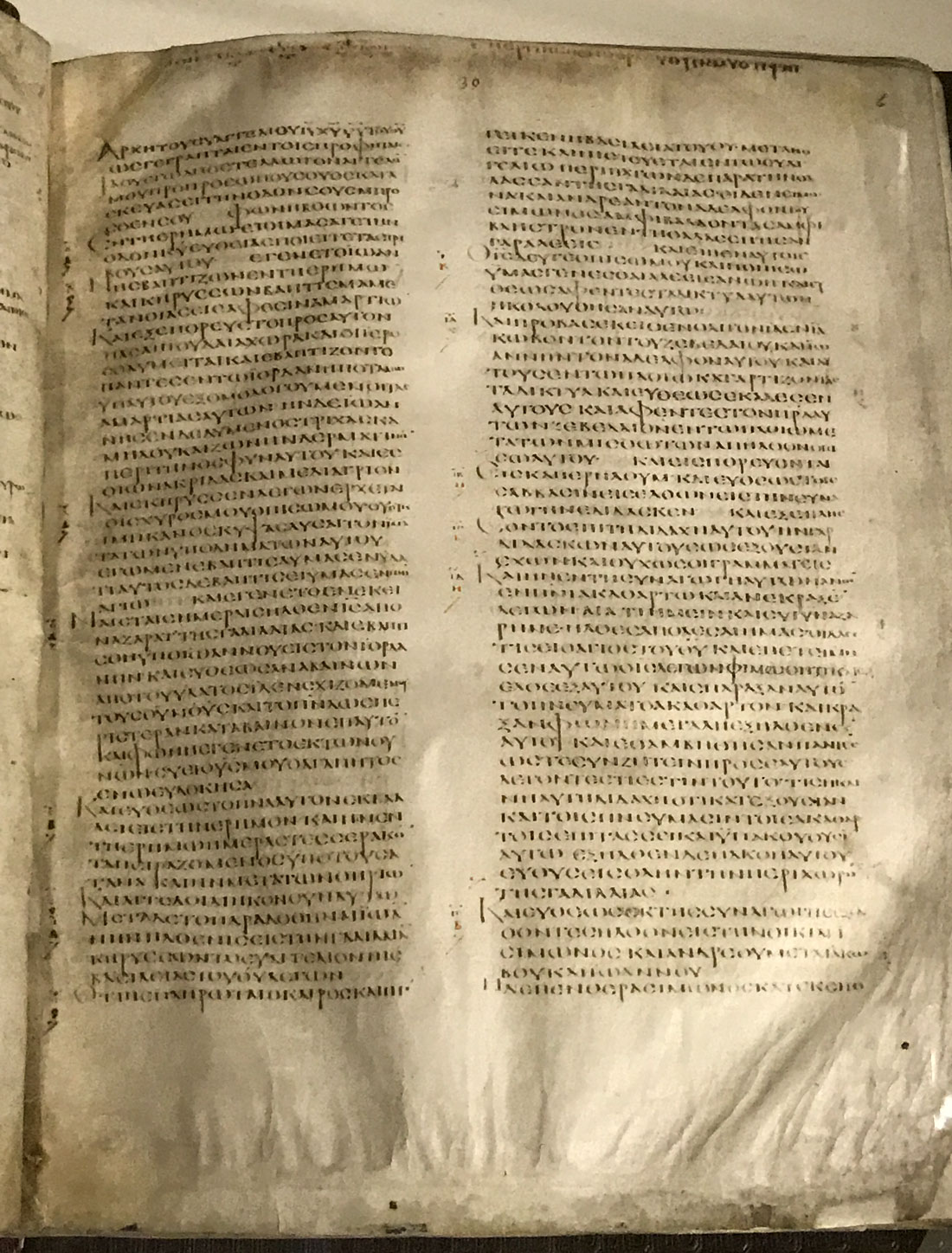

A page from the 5th century Codex Alexandrinus, also one of the three earliest manuscripts that contain the Bible in Greek. British Library.

No original manuscripts written by the authors of the New Testament survive, so all translation has been done from copies of copies. As older manuscripts have come to light in modern times, scholars have revised their views on how to translate the Bible. For example, the 4th century Codex Vaticanus, one of the oldest copies of the Bible, was not studied carefully until the 19th century but has caused translators to revise their views. The Codex Sinaiticus is similar. Most of it was found at Saint Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai Peninsula in the 19th century.

Between 382 and 405, the priest Jerome translated most of the Bible into Latin to form the Latin Vulgate. He based his translation on the Hebrew for those books of the Bible preserved in the Jewish canon and on the Greek text for books considered canonical by Catholic and Orthodox Christians and non-canonical by Protestants. Jerome’s object was to make the Bible more accessible to common people. However, as the Roman empire broke up and languages such as Italian, French and Spanish developed in various parts of it, Latin and Jerome’s version became the language of the church elite and largely inaccessible to common people.

The earliest surviving complete manuscript of the entire Bible in Latin is the Codex Amiatinus, a Latin Vulgate edition produced in 8th-century England at a monastery. The Latin Vulgate has continued to be produced up to the present day in various versions. It was the most common edition of the Bible and the most influential text in Western Europe for more than a thousand years from 400-1530. It had an even greater influence on the area’s culture through the Middle Ages and Renaissance than the King James Version later had. It permeated art, architecture, hymns and drama and was the focus of prayer, religious liturgy and private study.

The Vulgate had a major influence on the development of English and other languages, especially in religious matters. Many Latin words were taken from the Vulgate into English nearly unchanged in meaning or spelling. Creation, salvation, justification, testament, publican, apostle, and angel are all derived from Latin in the Vulgate.

The German Reformed movement retained and extended the use of the Vulgate in theological debate, and it was a reference text in published Latin sermons of John Calvin in the 1500s and of other reformers. The result was a broadening appreciation of Jerome’s translation in the Protestant Reformation movement.

The Catholic Church in the Council of Trent (1545-1563) considered the Vulgate the standard for qualifying books for the canon. The church declared that the Vulgate by many years of usage had been approved as authentic and should not be rejected under any pretext. This approval held – Pope Pius XII declared in the 20th century that it was "free from error whatsoever in matters of faith and morals."

The Vulgate occupies an important place in the history of Biblical translation, as later Bibles in different languages were based on it. These in turn heavily influenced the cultures of the target languages.

Translation of the scriptures into the vernacular languages of various regions has a long, tortuous history. The Bible was translated into the now extinct language of Gothic in the 4th century, and that language is known primarily through a 6th century copy. A century later, Saint Mesrob translated the Bible using the Armenian alphabet which he also invented. Syriac, Coptic, Old Nubian, Ethiopic and Georgian translations were made about the same time.

The earliest extant Bibles may have come about because the Emperor Constantine commissioned 50 Bibles.

Creation of a copy of the Bible was laborious because it had to be written out by hand. If a scribe accidently omitted a word or line or wanted to comment about a text, he would leave a note in the margin. This introduced uncertainty because later scribes copying a copy didn’t always know whether a note was intended as part of the text. Over time, different locations evolved different versions of the Bible in this way.

Translation of the Bible into vernacular languages was frowned upon in England during the Middle Ages, but there are fragments of translations into Old English and other languages because parts of gospels were translated for incorporation into a variety of other books. The earliest English versions of parts of the Bible were made in the 600s.

In about 900, some passages of the Bible were circulated as part of a law code. In about 990, a version of the four Gospels in idiomatic Old English appeared in the West Saxon dialect and is known as the Wessex Gospels. Seven manuscript copies have survived. At about the same time, an independent translation of the first six books of the Old Testament also was produced.

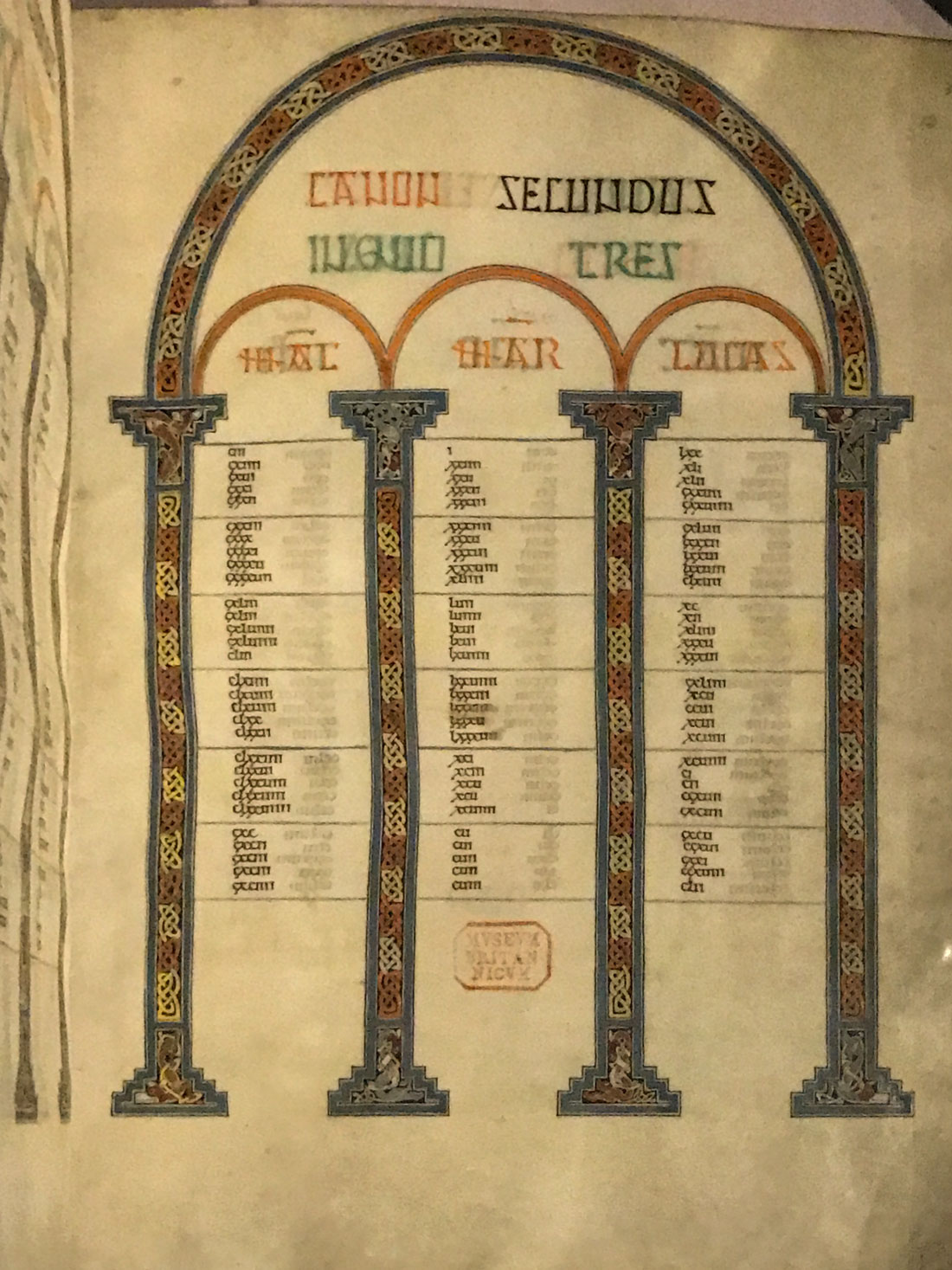

A page from the Lindisfarne Gospels, which probably were created between 698 and 721. A 10th century priest, Aldred, added an Old English translation above the words of the Latin text to create the oldest translation of the gospels into English.

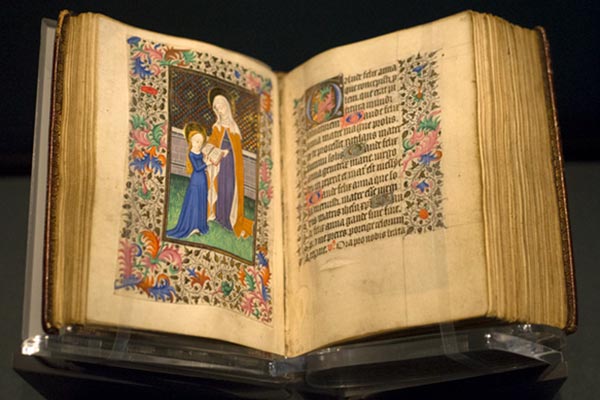

From the Norman Conquest of England in 1066 to about 1500, Bible translation languished because the elite of Western Europe preferred to use Latin as a literary language. Pope Innocent II in 1199 banned unauthorized versions of the Bible. However, some vernacular translations were allowed and parts of the scriptures showed up in elaborately decorated Bible picture books and Books of Hours. The Bible was translated into old French in the late 13th century and into Czech in about 1360.

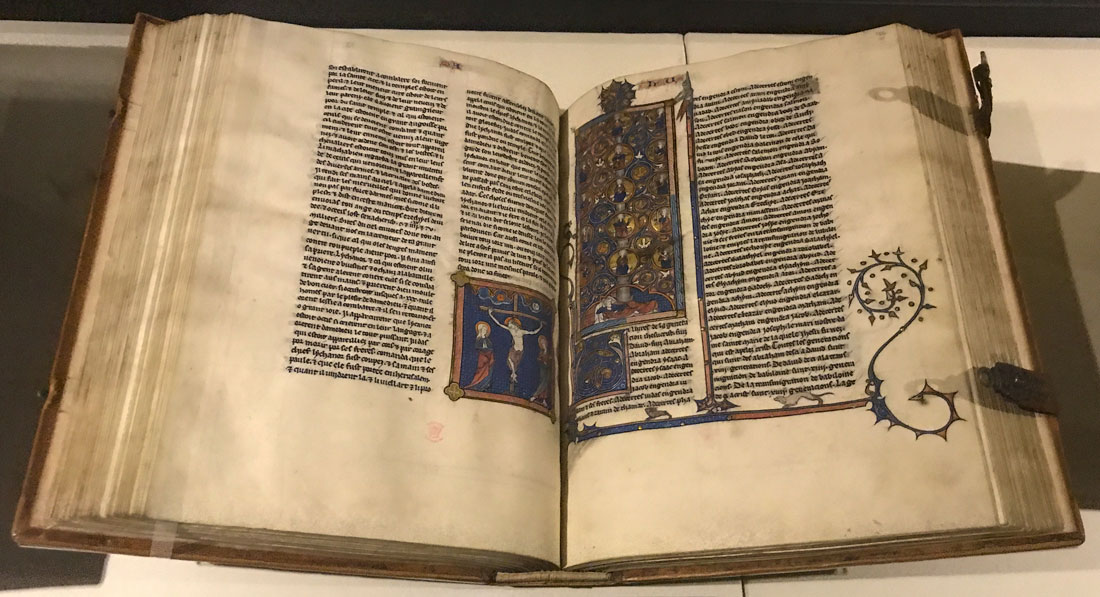

The 13th century Paris Bible, opened to the first page of the book of Matthew which shows Christ's family tree. British Library.

In the late 14th century, John Wycliffe translated the Latin Vulgate to produce the first complete English language Bible, but it was banned in 1408. The pope accused Wycliffe of “vomiting out of the filthy dungeon of his heart most wicked and damnable heresies.”

The first version adhered to Latin word order and thus was difficult for English lay people to understand. A later version was adjusted to align better with English grammar. Wycliffe died in 1384. His bones were exhumed and destroyed in 1427 on the pope’s orders, and he was labeled “a disciple of antichrist.” From King Richard II to the English Reformation, people who read Wycliffe's Bible were persecuted.

Czech priest Jan Hus also was burned alive for translating the Bible into his own language. A statue in Prague’s main square honors him today. The suppression of these men, who believed that societal change would come only as people had the means to educate themselves such as vernacular Bibles, triggered a counter-movement. Protestant supporters formed military forces that defeated crusades sent by the pope in what came to be known as the Hussite Wars of 1419 and 1434.

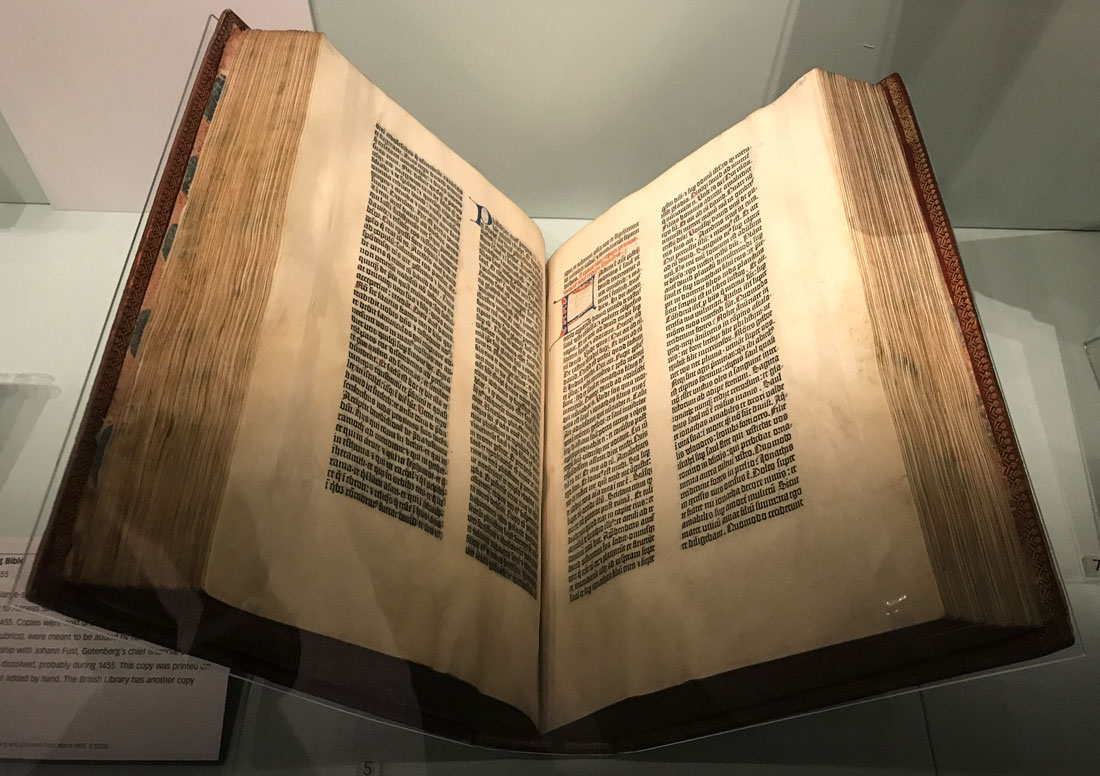

Johannes Gutenberg and John Fust produced the first Latin Vulgate published by moveable type printing in 1455, the famous Gutenberg Bible. It can be argued that the Reformation would not have been possible without the diaspora of knowledge of the Bible that came because of printing. In the 15th century, Hungarian and Catalan translations of the Bible appeared.

This Gutenberg Bible at the British Library was printed on vellum.

Revived study of ancient Greek led to new translations, including a Greek New Testament reconstructed in 1515-16 from several Byzantine texts and a Greek translation from the Latin Vulgate by Desiderius Erasmas. Church officials disliked his preference for Byzantine Greek over the Latin Vulgate.

In 1550, an edition of the Bible with notes on variant readings from different manuscripts was printed in Paris. The Greek text of this edition along with that of Erasmus became known as the Textus Receptus or “received by all.” It was influential in future translations of the Bible. Later editions have incorporated research from discoveries of Greek papyrus fragments that date from within a few decades of the original New Testament.

England was one of the last countries in Europe to have a printed vernacular Bible because the Roman Catholic Church was considered the final authority in the interpretation of the scriptures until England broke with the church. The Church believed that encouraging private interpretation of scriptures led to heresy.

Churches of the Protestant Reformation translated the Greek of the Textus Receptus to produce vernacular Bibles, including Martin Luther’s 1534 German one and Polish, Spanish, Czech and English versions in the 1500s and 1600s. Luther’s Bible was the basis for Danish, Swedish and other translations. At the time, Germany had several regional dialects which became united partly because of the influence of Luther’s Bible. The French Bible was translated in 1530.

The priest William Tyndale was a student in Cambridge, England, when Luther posted his famous theses. He agreed with Luther’s views, and began to translate the scriptures into English. Tyndale used the Greek and Hebrew texts of the New Testament and Old Testament in addition to Jerome's Latin translation. Tyndale's New Testament translation of 1526 was revised in 1534, 1535 and 1536. He was the first translator to use the printing press, which enabled the distribution of several thousand copies of his New Testament translation throughout England.

Tyndale's Bible. British Library.

He told one educated acquaintance: "I defy the Pope and all his laws: and if God spare my life, ere many years I will cause a boy that driveth the plough shall know more of the Scriptures than thou dost.”

He declared that he wanted the Bible to reach the eyes of all women, Scots and Irishmen, Turks and Saracens, farm workers and weavers.

It was a dangerous undertaking. King Henry VIII decided Tyndale had violated canon law because Latin was the only accepted language for scripture in translation. Tyndale sought a safe haven in Hamburg to work on his translation. However, at one point he had to flee with a few printed sheets and finish printing work on another press. Copies of his books were burned, including some at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, and few of the earliest survive. Dozens of people were executed for owning copies of Tyndale’s Bible or trying to smuggle them into Britain.

The Catholic Church objected to Tyndale’s “pestilent glosses,” or notes and claimed he had deliberately mistranslated some passages to promote heretical views and anticlericism. Cuthbert Tunstall, the bishop of London, set out to destroy copies of Tyndale’s New Testament, and cut a deal with an Antwerp merchant to secure them. The merchant told Tyndale the bishop of London wanted to buy his Bibles. Tyndale agreed, hoping to pay debts and finance new editions of the Bible.

However, Henry VIII’s troops captured Tyndale, strangled him and burned him at the stake in 1536 before he finished his translation of the Old Testament. Miles Coverdale compiled the first complete printed translation into English, using Tyndale’s New Testament, the published portions of Tyndale’s Old Testament and Coverdale’s own translations of the rest of the Old Testament from Latin and German.

Tyndale's Bible was one of the most influential English translations of the Bible ever made. Subsequent translations relied heavily on it.

John Rodgers, working under the pseudonym Thomas Matthew to protect himself, produced Mathew’s Bible in 1537, also based largely on Tyndale’s and Coverdale’s work. Henry VIII, who had a change of heart after converting to Protestantism and establishing the Church of England, approved of this Bible.

Two years later, The Great Bible compiled by Coverdale was issued to fulfill a decree that each church should make the largest possible copy of the Bible available in a convenient place for parishioners to read. Large crowds gathered to read it. Another version, the Bishops’ Bible, appeared in 1568.

Henry VIII tolerated the Bibles because the publishers omitted mention of Tyndale’s involvement in translating them. However, he became angry because sacred words from the Bible were “disputed, rimed, sung and jangled in every ale-house.” He decreed that no notes or annotations were to be allowed in any editions, and those in existing Bibles were to be blacked out. He allowed only the upper classes to possess Bibles. A year before he died, all versions were prohibited except for the Great Bible, which was so costly and large that no private citizen could own it. His decree led to the burning of more Bibles in 1546 that included all versions except for the Great Bible. As a result, leading religious reformers fled England for Europe.

Under King Edward VI, restrictions on translating and publishing the Bible were lifted. Queen Mary, who was Catholic, maintained this policy in general, but ordered versions with overtly Protestant notes burned. Reformed versions continued to be used secretly, however. English scholars driven into exile published the Geneva Bible, the first English Bible divided into verses. William Whittingham, who was married to John Calvin's sister, compiled the Geneva Bible, which the Church of England considered too Calvinist.

The first complete Roman Catholic Bible in English was the Douay–Rheims Bible. It was translated from the Latin Vulgate and completed in 1610 in France. Its notes were strongly anti-Protestant and its preface said that Protestants had cast “the holy to dogs and pearls to hogs.” Protestant scholar William Fulke issued a point-by-point refutation of the Douay-Rheims Bible’s New Testament that compared it and the Bishop’s Bible in parallel columns. The work made the Douay-Rheims Bible more popular than it probably would have been otherwise. The Douay-Rheims version was the standard Catholic English-language Bible until 1941.

King James ordered a new translation of the Bible, which was completed in 1611 and remains the English-language standard today. A 1998 analysis of the King James Authorized Version revealed that Tyndale's translation made up 84 per cent of the version’s New Testament, and 75.8 per cent of the Old Testament books that he translated. The King James Version was translated by 47 translators using a wide range of source texts. It had a profound impact on English literature and culture. It is by far the most commonly read English version. In the United States, with 55% of survey respondents who read the Bible reporting using it in 2014, followed by 19% for the New International Version, with other versions used by fewer than 10%.

A King James Bible from 1653. Brigham Young University.

A movement called the King James Only movement is espoused by evangelical conservatives, High Church Anglicans and Baptist churches that assert that it is the greatest English translation ever and all later English translations are corrupt. Adherents' views range from believing that the version was divinely inspired and sanctioned by God and should never be changed to those who believe that it is a new revelation and should be the standard by which other translations are corrected. Some adherents simply believe that it is an exemplary translation that should be used because it is familiar and they are accustomed to its style. Some insist that modern translations included corruptions that Origin introduced into the Septuagint or corrupted Alexandrian Greek text.

Nonetheless, the King James Bible has been revised a number of times. A version of it by American scholars is the American Standard Version that appeared in 1901.

The Bible since the King James Version has become the most translated book in the world, largely because Christian organizations have translated it into many languages. Making it available in vernacular languages became the main Protestant missionary tool. During the 19th century, translations of the Bible were published in about 400 languages, and many more were added during the 20th century.

In 1999, Wycliffe Bible Translators announced Vision 2025 — a project that intends to translate the Bible into every language. In October 2019, the organization estimated that translation still needed to be done in 2,115 languages spoken by 171 million people. There are some 3,900 languages that don’t have a translation of any portion of the Bible, but many don’t need their own Bible because they are very similar to other languages that have Bibles or they are spoken by very few people.

There is always a tension between translating a text word for word or instead going for meaning with a different idiom that has similar meaning in the target language. Translations that preserve idioms word-for-word can be harder for readers to understand. Translating for meaning relies more on the translator’s theological, linguistic or cultural understanding. This has risks, because translators have biases. Some translations adhere to particular doctrinal views such as ways of referring to God. The Purified Translation of the Bible, produced by a group that believes Christians should not drink alcohol, translates wine as grape juice.

Word-for-word equivalence is not always attainable if a source language and culture differ greatly from a target one. When it is achievable, it can help readers explore how meaning was expressed in an original text, preserve original information and highlight historical nuances.

Some versions of the Bible, such as the English Standard Version, emphasize preserving the original of individual words and phrases over being understandable to modern readers. Others such as the Living Bible emphasize rendering the intent of the original understandable to modern readers. Some translators believe that rendering translations entirely faithful to the source language makes them awkward, and that translations should instead appear to a native speaker of the target language to have been originally written in that language.

The debate has increased with the introduction of gender neutral and feminist versions, especially whether to translate pronouns referring to God as he, she or it. Scholars created a special Chinese character to render the pronoun for God into the Chinese language. Some scholars argue that English is so skewed toward the male gender that it renders God as male in cases where the original manuscripts don’t warrant it. The argument goes back to doctrinal perceptions of the nature of God.

In some ways, translating the Bible in such a way that it is similar to the target spoken language harks back to the ancient tradition of targum, which were translations necessary in the first century when the common Jewish language was Aramaic rather than Hebrow. The translator would expand a translation into a sermon with paraphrases, explanations and examples. Gradually, some of these were written down and came to be seen as authoritative. They are used today as sources in some editions of the Bible. They illustrate the longstanding relationship between written text and spoken word in Biblical translation. Samaritan targum were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Another scriptural source was letters such as those of the apostle Paul, which also explained Christian doctrine. The letters themselves refer to connections between them and spoken sermons Paul delivered in person.

Latin texts are another area in which the spoken and written languages interacted. The Latin Vulgate was based on a collection of biblical manuscript texts, many of which were prepared for the local use of Christian communities.

Biblical scholarship has continued to evolve. Discovered Syriac translations of the New Testament, for example, date from as early as the 2nd century. Syria is believed to be where the gospels of Matthew and Luke were written, and Syriac is closely related to the Aramaic dialect spoken by Jesus and his apostles. Syriac manuscripts of the New Testament come from Lebanon, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Assyria, Armenia, Georgia and other locations. There also are many Coptic versions of the Bible, including some of the earliest translations in any language. Apocryphal texts also survive in Coptic, most notably the Gnostic Nag Hammadi library. Coptic remains the liturgical language of the Coptic Church. There are translations into other Egyptian dialects such as Sahidic as well. Knowledge of the Sahidic manuscripts was lost until they were rediscovered in the 18th century. Ancient cuneiform languages such as Sumerian and Hittite have helped advance interpretations of the Old Testament. Early English Bibles were based on Latin translations or a small number of Greek texts, but modern ones use a wider variety of the ancient manuscripts. Translators cross check the various sources and make judgements based on comparisons. There are hundreds of differences between the texts, and many disagreements over passages and text notes.

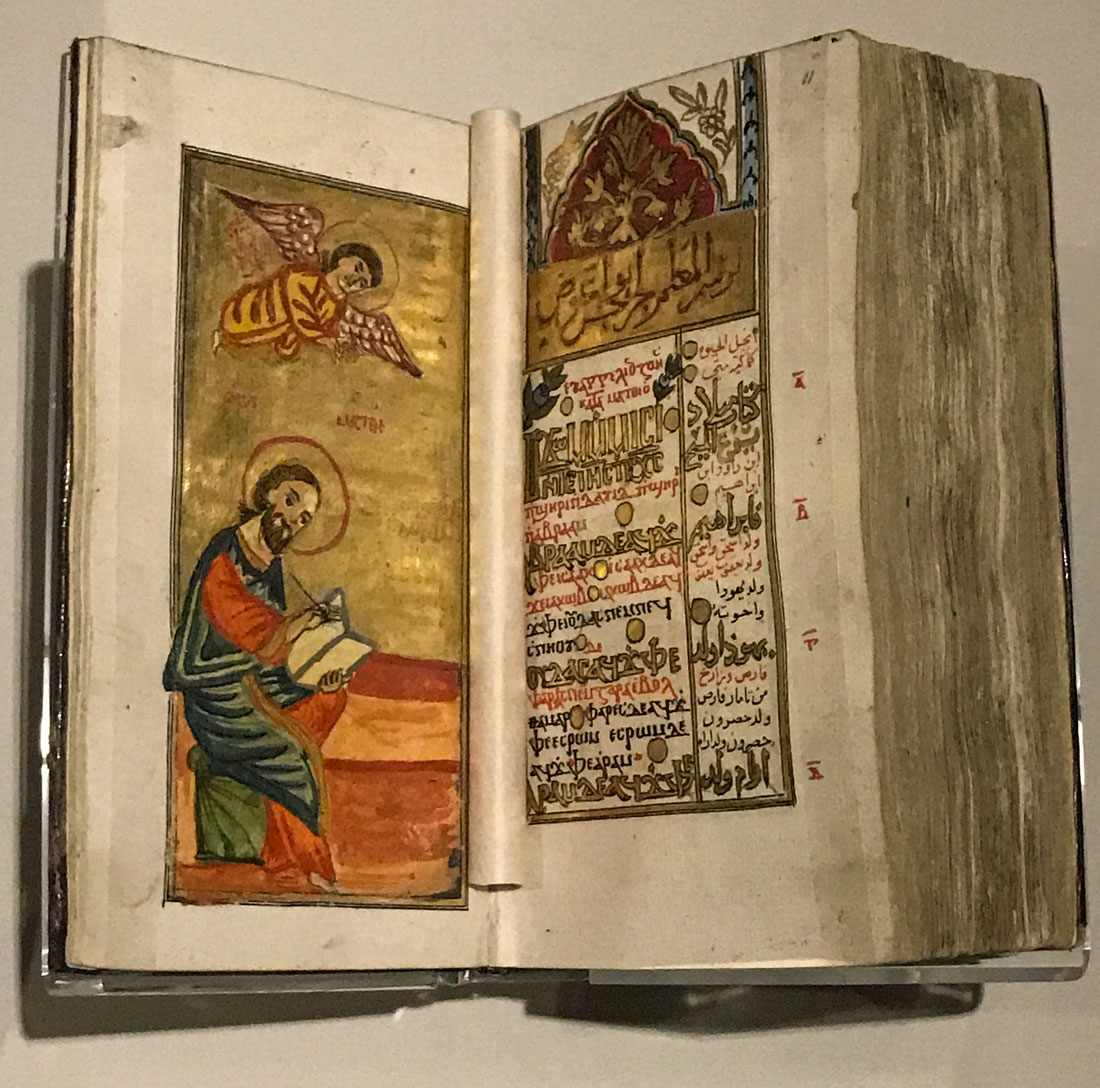

An early 18th century Coptic version of the Four Gospels. British Library.

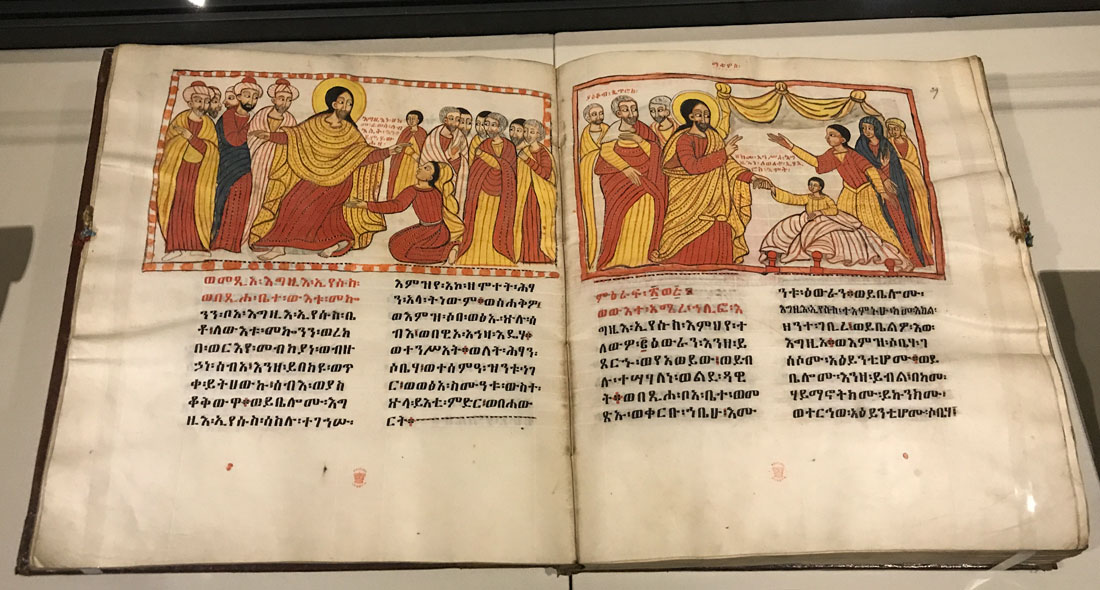

An Ethiopic version of the four gospels from the 17th century. British Library.

Punctuation is a problem requiring interpretation, as ancient Greek and Hebrew manuscripts had little or none of it. Quotation marks are especially tricky, as it can be difficult to determine where a direct quote ends. Placement of a comma can change the meaning of a verse. The translator has to add capital letters and paragraphs, as ancient documents didn’t have them. Other decisions involve how to translate ancient measuring systems, whether to use archaic forms of English such as thou and thine and whether to capitalize pronouns that refer to deity, which wasn’t done until the 20th century in any texts.

Most translations are made by committees of scholars and rely on footnotes where there are alternative translations of text. Translations of a single text are mainly done for the use of scholars or specific audiences such as particular denominations.

The Internet has greatly increased the number of English Bible versions in digital form. Some versions link the Bible text to articles and image galleries. There are more than 1,700 versions of the Bible in more than 1,200 languages available digitally on bible.com and a similar number on the American Bible Society's bibles.org.

The Bible also has been translated into a number of sign languages.

The Bible has been translated into many African, Chinese, European, Hawaiian, Indian, Indonesian and Malaysian, Native American, Oceanic, Filipino, Russian and Taiwan languages. It also has been translated into fictional languages such as J.R.R. Tolkien’s Quenya, LOL Cat which is a slang language of the internet, Klingon, N’avi (the language of the film Avatar), and Láadon (a women’s language from the Native Tongue trilogy).

The history of translation is a fascinating tale of adventurous missionaries who fanned out over the globe in the 19th and 20th centuries to learn foreign languages and then translate the Bible into them. In the process, they have had to grapple with the literary traditions of the languages.

For example, Tibetan is a mixture of high literary language and specific regional vernacular spoken languages. Translating the Bible into a regional vernacular will make it more easily understood, but only within a limited geographic area, and it will be viewed as less prestigious than translating it into the high literary language. Taking a middle course will make it harder to understand but it will have a wider geographic reach. The high language will require readers to learn the literary language to understand it. The first Tibetan translation of the New Testament, by a Moravian missionary, was in the high literary language. Since then, other translators have taken on translating it into regional vernaculars.

Sometimes, when the original documents survive only in translation, scholars try to reconstruct the original text by translating the document back into the original language. Scholars who believe that the New Testament was originally written in Aramaic try to prove this by showing that difficult passages in the Greek text make much more sense when translated into Aramaic.

Bible translations have greatly shaped languages into which they were translated. In Spanish- and French-speaking regions, the influence of Bible translations shapes the entire landscape, music, literature, art and names of both people and places.

Check out these related items

Illuminated Manuscripts

Illuminated medieval manuscripts preserved culture and religious beliefs and set a foundation for book design and art styles.

China’s Stone Scriptures

Thousands of Buddhist scriptures carved in stone and buried for centuries are among China's greatest cultural treasures.

Portraits of Mary

Mary, the mother of Christ, may be the most prominent visual icon in the world. We explore her history.

Resting Place of Kings

France's dazzling royal necropolis, the Basilica of Saint Denis, is also the birthplace of Gothic architecture.

The Land of Junipero Serra

Junipero Serra's "sainthood" is controversial, but the extent of his cultural impact on California is indisputable.

The Tower of London

The Tower of London, enduring symbol of the British monarchy, combines royal pageantry with warfare, court intrigue and executions.