Behind the Mask: Beijing Opera’s Past and Future

Photos by Forrest Anderson

The new Marvel movie, Shang-Chi and The Legend of the Ten Rings, has a murderous henchman in a Beijing opera mask who moves at lightning speed and engages in a martial arts fight with the movie’s hero.

The film is placed in modern San Francisco, but draws on elements common to Beijing opera – Kungfu sword fights, saturated colors, heroes with superpowers, dramatic music and clever lines.

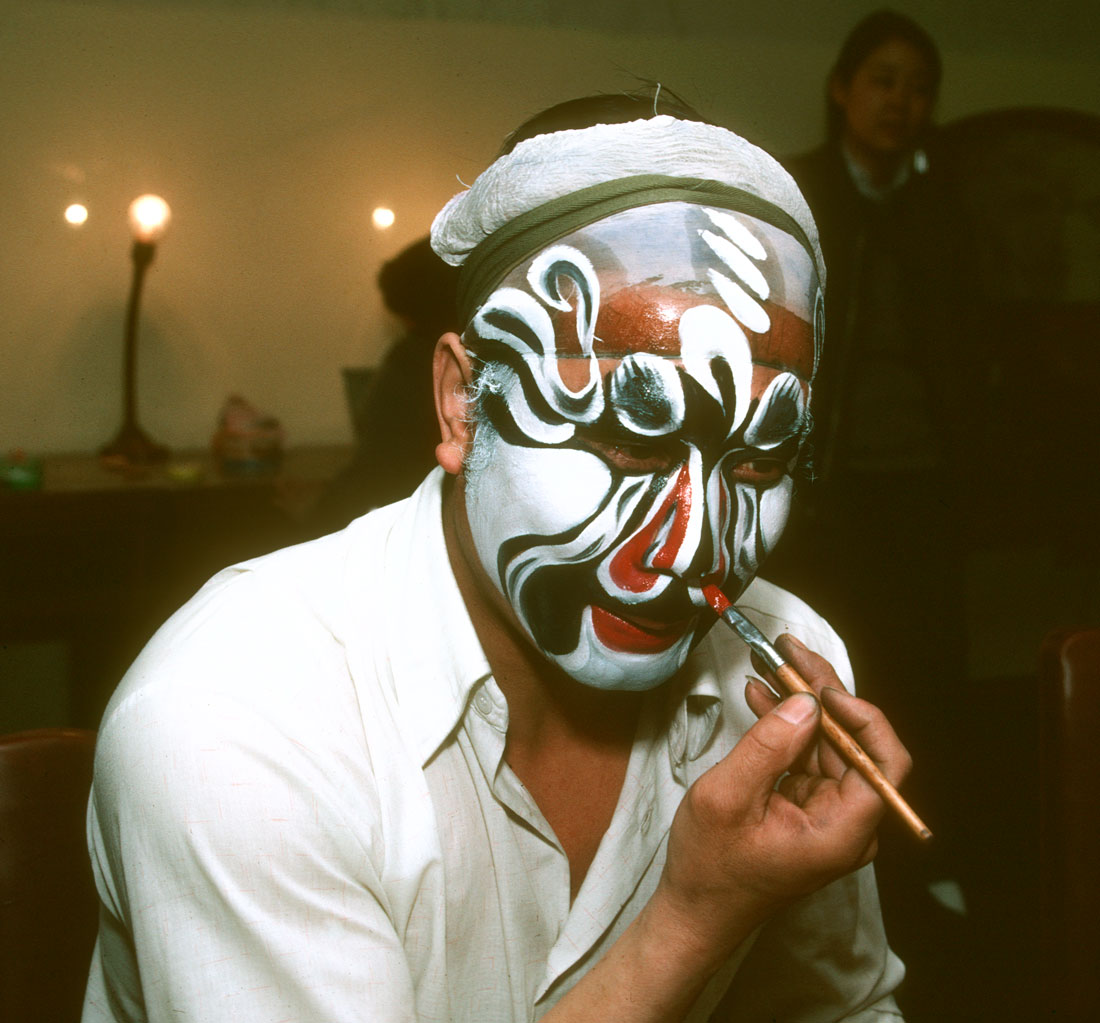

These elements take me back to a chance encounter between my daughter and the daughter of a Beijing opera star in a market in Beijing, China, that led us down a rabbit hole into the core of Chinese history and culture. The young woman and her multi-generational family of Beijing opera actors welcomed us warmly into a world centered around one of China’s most iconic art forms. We shared home-cooked dinners while discussing Beijing opera, went behind the scenes at China’s most famous opera theater to photograph actors painting their faces with iconic masks and posing in elaborate costumes. We watched as they brought the stories and legends of China to life on stage.

At the same time, while researching the impact of China’s 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution, I became acquainted with China’s leading Beijing opera playwright, Wu Zuguang, and his Beijing opera and film star wife, Xin Fengxia. Wu, who authored 40 plays and also directed films, was a legend in Chinese literary circles but was utterly unostentatious. We sat at his kitchen table munching on sliced ham, bread and dill pickles while he snowed me out with his brilliant, outspoken insights into Chinese history, current politics and art.

Xin was more personal – telling me about the rigorous training that made her one of China’s top Beijing opera stars and giving a wrenching account of persecution and crippling beatings she endured after Mao Zedong’s wife Jiang Qing became jealous of her popularity. “I hate Jiang Qing! I hate Jiangqing!” Xin declared again and again, her eyes flashing and her beautiful face hardening with anger.

This foray into the elite Beijing opera community was a vibrant multi-colored window into Chinese culture, history, politics and the performing arts. Beijing opera is a highly distilled multimedia and multi-disciplinary art in which music, sophisticated dialogue, dance, exquisite costumes and makeup, acrobatics and martial arts are combined to present the most famous stories from thousands of years of history and legend.

Such productions to convey morality stories, legends, and tales of romance, tragedy and comedy have been popular in China for thousands of years. Traveling troupes with distinctive regional styles once performed at every festival and at weddings, funerals, birthdays and other special occasions. At one time, it was a rare day that one could walk through a mid-sized Chinese town without coming upon such a performance. Storytellers at teahouses and streetside puppet shows drew on the same stories, sound effects and visual techniques.

China was a Confucian society, and performers modeled for their audiences what good and evil looked like, how people were expected to behave, and the consequences of bad behavior. The productions conveyed history to ordinary people, with tales of emperors and warriors, loyal and treacherous ministers and concubines as well as the poor.

In 1790, four great opera troupes from China’s Anhui province performed in the court and for the public to celebrate the emperor’s eightieth birthday. In 1828, Anhui troupes and troupes from China's Hubei province performed together, and the synthesis of their styles developed by 1845 into what is called Beijing opera (also called Peking opera).

There were other influences as well – Beijing opera’s music is believed to have originated from the music of the puppet shows of Shaanxi province, and the exaggerated dialogue used in Beijing opera is an archaic form of Mandarin Chinese that is closest to modern dialects of Mandarin from the provinces of Henan and Shaanxi. Many of Beijing opera’s staging, performance and aesthetic conventions come from imperial court customs and rituals.

Beijing opera was looked down upon as vulgar entertainment until the 1860s. The Xianfeng emperor died in 1861, and his concubine Cixi, the mother of his only son, ruled China for the next half century. She was a passionate fan of Beijing opera who had special theaters with complex machinery for plays built at her palaces. Her support helped usher in the golden age of Beijing opera which lasted into the early 20th century. Cixi watched some 260 operas at her grand theater in the Summer Palace in Beijing. Actors took up residence in her court and taught and performed. One of the greatest honors her courtiers could receive was an invitation to a performance. She sat opposite the theater stage in a hall while her ministers sat on surrounding porches.

The Summer Palace theater was restored in 2013, with skylights, pits, pulleys and an actual well on stage from which water could be drawn. Beijing opera and court dances now are staged there for tourists. Cixi is a main character in a Beijing opera called “Deling and Cixi,” about her and her outspoken lady-in-waiting.

To the uninitiated, a Beijing opera is difficult to understand although printed programs with a play synopsis are provided at theaters and subtitles are projected so audiences can understand the dialogue. Some theaters that cater to foreign tourists also project English subtitles.

Beijing opera is a highly distilled form of Chinese culture to the point that it is almost a code system. All parts of the performance are stylized and symbolic, from the costumes and the highly sterotyped roles to the colors of masks, props, music, allegorical references in the dialogue, and even the way in which an actor strokes his beard. Herein lies both Beijing opera’s cultural richness and its incomprehensibility to foreigners and many younger Chinese. Understanding Beijing opera requires a knowledge of Chinese history and culture as well as the meaning of the symbolic conventions used.

Beijing opera has four main roles – Sheng, Dan, Jing and Chou.

The Sheng is the main male role, who can be a middle-aged bearded man or a young beardless one.

Dan is any female role, of which there are several varieties - powerful older women, little girls from the lowest classes, elderly women and women warriors.

Jing are characters in Beijing opera masks, which typically are painted on their faces. The masks symbolize the personality and destiny of a character and have nothing to do with race or skin color. The masks are ancient, descending from primitive masks used by ancient Chinese in religious rituals.

Red face paint symbolizes loyalty, bravery, uprightness and heroism. Black indicates honesty, straightforwardness and impertinence. A character with a white-painted face is sinister, cunning and treacherous. A green face denotes that a character is stubborn, surly, impetuous and lacks self-restraint. Yellow indicates a person is fierce, ambitous and coolheaded. Blue-faced characters are fierce and astute. Purple-faced ones are upright, sophisticated and cool headed.

Jing actors must be skilled in painting their masks, as they help the audience follow a plot. The most accomplished performers also can change their faces to indicate their inner feelings by blowing black dust hidden in their palm so that it blows back into their face, manipulating their beard so that it changes from black to gray and then white to show anger or excitement, or pulling down a mask that has been hidden on the top of their head to express feelings of happiness or sadness.

Chou are male clowns who play secondary roles. The word “chou” means ugly in Chinese, and reflects the idea that a clown’s combination of ugliness and laughter drives away evil spirits. Chou can be merchants and jailers, which were considered lower class positions, or minor military roles. A character playing a Chou need only powder his nose white to convey his role.

Costumes reveal rigid hierarchical roles – a princess, prime minister, general, hunter, fairy, fortuneteller, warrior. Dragons embroidered on robes indicate an emperor, and phoenixes an empress. Good luck symbols, icons from Buddhism and Taoism, or symbols indicating court ranks are clues that help audiences understand the characters.

Beijing opera performance were historically done outside, and developed simple symbolic props to represent experiences. A horse whip signifies galloping on a horse. Two chairs on each side of a table denotes a bridge. Performers dancing with umbrellas indicates a storm. In recent years, however, modern multimedia effects and props have been added to some Beijing opera performances.

Beijing opera musicians use a variety of Chinese lutes, including ones with both shrill and mellow tones. Drums are used in battle scenes along with cymbals and large flat gongs. Clappers also are used. The methods and sounds of Beijing opera music are very different from Western music and sound dissonant to untrained ears, as rhythm is emphasized rather than harmony. Music is used like a sound effect, with certain chords meaning danger and the hammering of a large gong signifying confusion.

Most Beijing opera texts are based on series of couplets of seven or ten syllables each. Tension is maintained with short comments interspersed with music.

Different musical instruments are used with serious dialogue than those used with happier moments in a play. The dialogue draws from the ancient tradition of storytelling, which included sung stories or a mixture of sung and spoken stories in which rhyme, rhythm and sometimes musical instruments were joined. Chinese shadow and puppet plays, considered subsets of storytelling, use similar music. Recordings are sometimes mixed with live music so that a battle scene can be accompanied by percussion, firecrackers, and music.

In the early 20th century, new Beijing opera songs were written that mixed new and traditional Chinese and Western music. Chinese instruments were modernized. Social activists of the time saw Peking opera as a vehicle for social and political change among the then-mostly illiterate people of China.

The Chinese Communists used Beijing opera as a propaganda tool, and when the Communists rose to power in 1949, Mao Zedong demanded that Beijing opera help convert the masses to socialism. Scripts emphasized patriotism, socialism and equality between the sexes.

In 1959, Wu Han, a Beijing politician and historian, wrote several articles about Hai Rui, a Ming dynastry minister who was imprisoned for criticizing the emperor. Wu then wrote a Beijing opera play called "Hai Rui Dismissed from Office.” The play is a tragedy in which Hai risks his career to convey to the emperor the complaints of the people about corruption and abuses in official ranks.

The play was popular but it hit a nerve because a modern high official, Peng Dehuai, was purged at about the same time for criticizing Mao’s economic policies which caused a major famine. Chinese President Liu Shaoqi and other officials sidelined Mao’s policies in an effort to revive the economy. In retaliation, Mao plotted to eliminate Liu and his supporters, beginning in 1965 by criticizing Wu Han, who worked under a Beijing politician named Peng Zhen who was one of Liu’s closest supporters. Mao’s strategy was to eliminate Liu’s powerful supporters first, then Liu himself.

In 1966, one of Mao’s supporters, Yao Wenyuan, published an article claiming that Wu Han’s play was an attack on Mao. Wu Han’s career was destroyed and he died in prison in 1969. This was the opening salvo of the Cultural Revolution, and the purge of other cultural elites followed quickly. Mao and his actress wife, Jiang Qing, moved to overhaul China’s cultural sphere, including not just political figures but also prominent theater and Beijing opera artists and playwrights. Wu Zuguang and Xin Fengxia were among thousands of elite cultural figures who were persecuted, banned from practicing their art and sentenced to hard labor. Xin, one of China’s most popular actresses, was a prime target of Jiang Qing’s.

Beijing opera was targeted particularly because the Maoists saw it as depicting the old ruling class rather than workers who they elevated to the highest class status.

Jiang Qing spearheaded the creation of Eight Model Plays that were exclusively performed by government-sponsored theatrical companies. They all depicted characters struggling for freedom against the pre-Communist ruling class. These plays were widely performed and became an alternative form of Chinese theater that still is used today as government propaganda. Songs from these plays are known to most Chinese, as the plays were made into the only films allowed in theaters and the songs were played on the radio and in public settings everywhere. They incorporated Western and Chinese folk music.

The model play troupes that performed the plays were an opportunity for millions of ordinary Chinese to learn a musical instrument and perform. Today, some of the plays are a standard part of theater repertoire in China, and remixed versions have become popular hits and karaoke bar tunes.

Jiang Qing emphasized regional folk music and the government create research institutes that collected folk songs, which were incorporated into music education and reconstructed to reflect socialist messages. The most famous folk song, from Shaanxi province, was “The East is Red.” Other songs praised local industries and accomplishments. The songs were taught in public schools. Composers produced folk orchestra compositions.

Xin was forced to dig tunnels and became disabled when her knee was broken in a severe beating. She suffered a stroke that partially paralyzed her in 1975. When I knew her, she could move only slowly and haltingly. After the Cultural Revolution, Wu wrote a play based on Xin’s experiences and Xin wrote several booka about them.

Wu was a lifelong outspoken critic of government control over cultural issues, although he supported China’s opening up under Deng Xiaoping. He became a target again after he wrote an essay pleading for an end to censorship and was forced to resign for the Communist Party. He called for a reassessment of the army crackdown on the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989. Xin died in 1998 and Wu in 2003. Wu was the quintessential elite Confucian-style cultural figure who sees it as his duty to criticizes government overstep.

After the Cultural Revolution, the revolution and class conflict of the Cultural Revolution were played down, and traditional plays were revived. Western art forms such as Shakespearean dramas and some Western music were incorporated into Beijing operas.

The suppression of traditional Peking Opera during the Cultural Revolution had cost the art form many of its informed fans. Opening to the outside world also brought in foreign film and music which competed for audiences as well as bringing in new values that moved China further from the Confucianism that underpinned Beijing opera. Teahouses where Beijing opera had been performed had closed, replaced with restaurants and theaters or high-rise buildings. People’s values, lifestyles and media tastes had changed.

Beijing opera also faced problems of oversized troupes, shrinking and aging audiences and diminishing government support. Some Beijing opera companies changed their performances to please contemporary audiences. Beijing opera continued to decline in popularity from the 1980s on.

However, as China has become prosperous, many Chinese have turned to exploring traditional cultural roots and passing them on to younger generations. Confucianism, Beijing opera and other aspects of Chinese culture are taught in some schools and emphasized as part of a government campaign to promote traditional culture. This push is not without its critics, as some fear that the rehabilitation of traditional culture will lead to narrow-minded cultural nationalism that legitimizes oppression and presents a rigid conception of culture that ignores the diversity of the Chinese cultural tradition.

A core pillar of Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s agenda has been using traditional Chinese arts in the service of Chinese nationalism. To this end, Beijing opera is performed at cultural festivals such as this year’s Belt and Road and Great Wall festival in Lanfang, China. The festival’s purpose was to promote cultural exchanges with countries taking part in China’s Belt and Road Initiative from China to Europe.

The Shanghai Center of Chinese Opera’s 2021-2022 season includes 450 performances of traditional Chinese theater, including Beijing opera. Among these are classical works, socialist plays and new experimental works. Beijing opera continues to be a venue for playwrights and performers to work out the meaning of current and historical themes. Beijing opera dramatizes key human dilemmas – an orphan who survives although his disgraced family is all killed and later becomes a hero; people unfairly accused of murder and then exonerated; generals’ strategic ruses that save the kingdom from invaders, the adventures of people with superpowers. These themes are from well-known historic accounts, novels and legends.

Beijing opera has been challenged by competition from contemporary entertainment, low actors’ salaries and the destruction of neighborhood theaters for other development. Fewer than half of young graduates from Beijing opera academies continue in the profession after ten years.

Some Beijing opera artists are trying to keep the art form alive by fusing it with modern art forms such as film, video games and graphic novels. Beijing opera shares many characteristics with such forms - stereotyped characters, Kungfu sword fights, saturated colors and short, pithy lines.

This is one reason why Marvel’s films are widely popular with Chinese audiences – the culture delights in colorful heroes with magic powers and martial arts skills. Fusing Beijing opera with popular media forms may be one of the most effective ways to keep its cultural essence alive and widely relevant in modern China.

More photos of Peking opera

Check out these related items

Confucius Conundrum

Chinese-sponsored Confucius Institutes have taken an international hit because of broader controversial China policies.

Qing Ming Painting Resonates Over Centuries

China's most famous painting captured traditional life, the traces of which have survived into modern times.

A Classical Chinese Garden

Lan Su Chinese Garden in Portland, Ore., was built by artisans from the garden city of Suzhou, China, to demonstrate the basic elements of Chinese gardens.

China’s Walled Cities

Only scattered remnants survive of the many walled cities that once defined the Chinese empire.

Chinese Moments Published

Chinese Moments, our photo book on China in the turbulent 1980s and 1990s, has been published as an ebook and paperback.

Tiananmen Square

China's Oct. 1 celebration of 70 years of Communist rule centers on Tiananmen Square, one of the world’s most controversial places.