Beyond the Forbidden City

Photos by Forrest Anderson

The modern high rise city of Beijing has both obscured much of the imperial capital that once ruled the Chinese Empire, and revealed fragments of it that were closed to ordinary people in imperial times.

The Forbidden City, a walled rectangular compound of golden roofed palaces from which the past emperors of China ruled, is one of the largest and most popular historical sites in the world. However, the Forbidden City was just one part of the vast lands in the city’s center in which the emperor and his court lived and worked.

The Forbidden City was encircled on the north, west and south by a large park in which the imperial family once lived and carried out the functions of government. In the early 20th century, this park was broken up into separate parks and compounds, some of which were opened to the public, and the area has been greatly modified. However, understanding its history is central to an understanding of imperial Beijing and the city's culture today.

In modern times, as Beijing has burgeoned into a crowded, high-rise city of 20 million, the imperial parks around the Forbidden City and in other locations in the city have become a key part of the local culture. Many people go to a park daily to exercise alone or in groups, enjoy nature and gather with friends. On the weekends, families flock to the parks to relax and enjoy picnics. The parks are integrated with the daily and seasonal rhythms of the city. Exercisers gather in groups in the early morning, nannies take children to the parks in the mid-mornings to play, and retired people gather with friends at the parks, and couples stroll through them in the afternoon.

In the spring, people go to the parks to see the blossoming trees and flowers. In the summer, they boat on the lakes. They stroll beneath the colorful foliage in parks in the fall, and in the winter when it’s cold enough, they ice skate. When we lived in Beijing, we visited an imperial park almost daily for exercise and relaxation.

Beijing as a capital dates back more than 1,000 years to the Liao Dynasty, when the first imperial gardens and palaces west of today’s Forbidden City appeared. This project was steadily expanded in the subsequent Jin, Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties and was substantially modified in the 20th century under both the Republic of China and today’s Communist government.

Beihai Park

West of the Forbidden City are three large lakes called seas – the Northern Sea, or Beihai; the Central Sea or Zhonghai; and the Southern Sea or Nanhai. These seas have an ancient history, as this area was a country resort for Emperor Zhangzong of the Jin Dynasty, which had its capital in southwestern Beijing. Zhangzong had a palace built on the island in the middle of the lake that is now Beihai.

About 50 years after Genghis Khan and his Mongol horsemen conquered China and launched the Yuan dynasty in 1215, the island was redesigned and the lake and its gardens were surrounded by a wall that enclosed them in the Mongol emperor Kublai Khan’s splendid new capital, the city of Dadu. Kublai’s palace has long been believed to have been located at Beihai Park, although archaeologists also have uncovered what they believe are foundations of a Yuan dynasty palace under the Forbidden City itself.

European explorer Marco Polo, who Kublai Khan received in his palace, described it:

“You must know that it is the greatest palace that ever was! The roof is very lofty, and the walls of the palace are all covered with gold and silver. They are adorned with dragons, beasts and birds, knights and idols, and other such things!... No man on earth could design anything superior to it.”

Kublai Khan (r. 1260-1294) drastically remodeled the capital to include palaces, city walls, moats, a canal and other features in the area around the Forbidden City area. His builders also created the grid-like street system for which Beijing was long known.

In 1368, Chinese rebels overthrew the Mongols and established the Ming Dynasty, with its capital far to the south in the city of Nanjing. However, the capital was moved back to Beijing two emperors later, after a Civil War over royal succession. The victor, the Yongle emperor, was eager to show that his claim to the throne was legitimate. He pulled out the stops to build an ideal Chinese imperial palace compound in the area where the Mongol capital of Dadu had sat. Yongle’s architects drew upon ancient records that described imperial palaces, symbols and religious ideology to create Ming dynasty Beijing, which was a triple walled compound with the palace at its center. For irrigation, they expanded the lakes west of the palace into the three “seas.” The lakes drew from an ancient legend of three magical islands beyond the Bohai Sea which had mountains on them. This legend had been part of imperial tradition for more than a millennium and had become a standard organizing principle for imperial gardens. As the mythical islands were believed to be the home of eight immortals who had an herbal medicine that conferred immortality on its partakers, using the design of three lakes with islands symbolized the dynasty enduring forever. The three seas and their surrounding gardens were called Xiyuan or Western Park during the Ming dynasty. They were the exclusive garden of the emperors and the royal family.

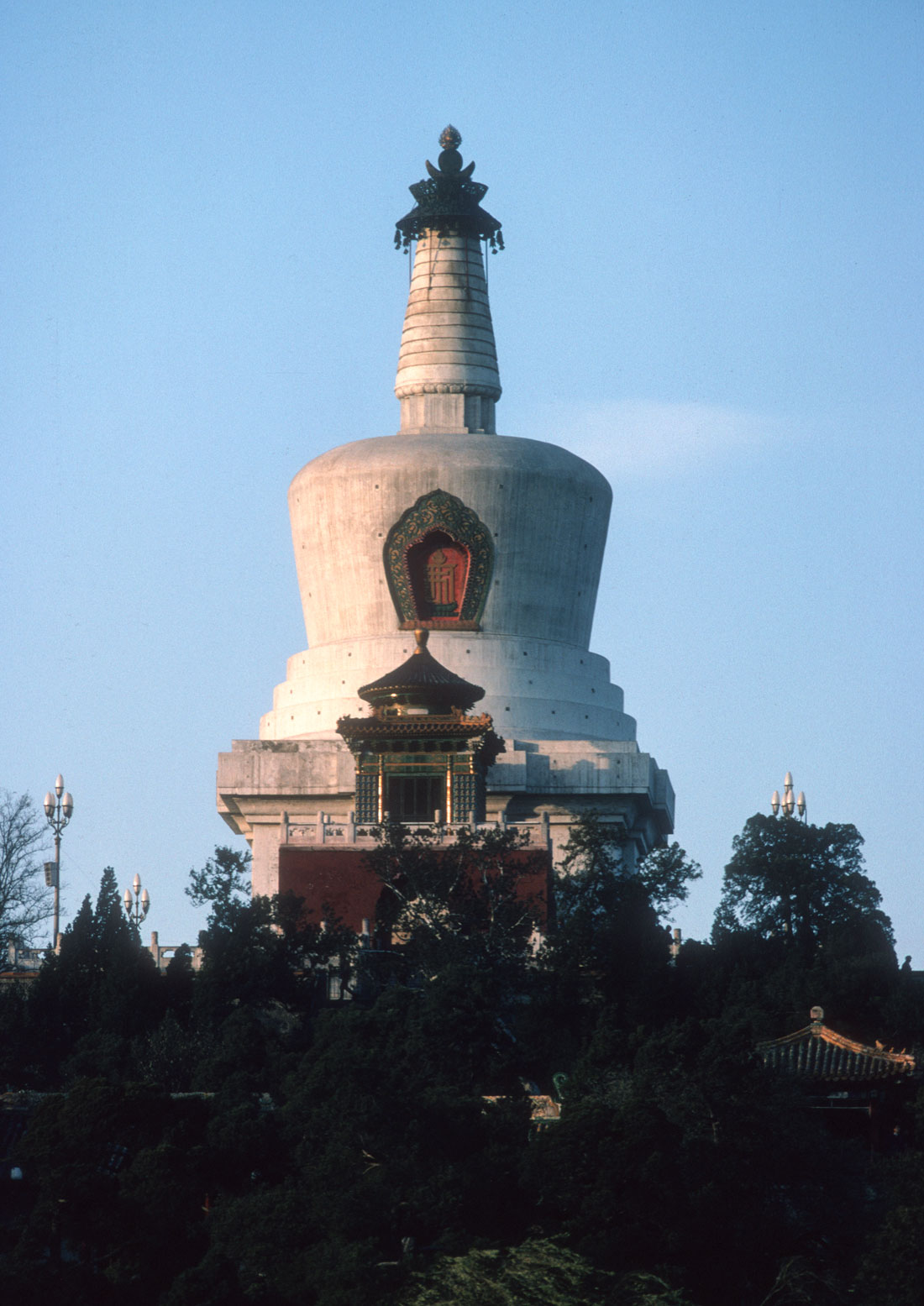

The Northern Sea, or Beihai, was associated with religion. In 1651, a 40-foot-tall white stone stupa was placed on the highest point on Jade Flower or Qionghua Island in the center of the Beihai Sea to honor a visit of the fifth Dalai Lama to Beijing. The stupa was religious, but also had a political rationale – it was built by the first emperor of the Qing Dynasty, Shunzhi, at the suggestion of a Tibetan lama to demonstrate both devotion to the Buddhist faith and unity among the various ethnic groups that made up the Chinese empire. It was a symbol aimed at consolidating the new dynasty’s authority. The stupa stands on a large stone base and has two bronze umbrella canopies with 24 bronze bells hanging around them. Inside the dagoba are Buddhist scriptures, a monk’s mantle and alms bowl and the bones of monks. From the dagoba at the top of the hill on the island, the entire park can be seen.

The stupa was destroyed in an earthquake in 1679, but rebuilt the next year. The devastating 1976 Tangshan earthquake again damaged it, requiring another restoration.

The park also includes other famous Buddhist temples. In front of the dagoba is Yong’an temple, a Ming-era monastery that got its name in the Qing dynasty. Bell and drum towers, several buildings and halls and stone tablets inscribed by the Qing emperor Qianlong are in this area.

On the north bank of the lake are five connected pavilions called the Five-Dragon Pavilion which were built in the Ming dynasty.

North of them is a long glazed brick wall with a colorful design showing nine dragons playing in the clouds, an imperial symbol. Created in 1402, it is one of three in China, the other two being in the Forbidden City and in the city of Datong.

The park has a number of small traditional Chinese gardens. One of the best is the Hua Po Creek Garden, which the Emperor Qianlong built to give the impression of a secluded, tranquil valley. In the northern shore area is a garden called the Quiet Heart (Jingxin) Studio, which dates from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Qianlong enjoyed sipping tea, listening to music played on a Chinese zither and enjoying the scenery there. This garden was enlarged in the Qing Dynasty, and its palaces, halls, pavilions, towers, corridors and artificial hills were a place for royal family members to rest and study. In the 1700s, the emperor turned it into a study for the crown prince. The Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908) often ate her meals in the garden, and it was there where the last emperor of China, Puyi, wrote his biography, From Emperor to Citizen.

In the park’s Hall of Received Light is a 1.6 meter-tall white jade Buddha that was presented to a Qing dynasty emperor by a Southeast Asian king. The jewel-encrusted statue was damaged during an invasion of Beijing by Western forces in 1900. The hall also has a large jade urn that was once used by Kublai Khan for storing wine.

On the northeast corner of the lake is a square palace called Little Western Heaven that was built for Qianlong’s mother’s 80th birthday. A Ming-era hall that was a lamasery in the Ming dynasty was recently restored.

One of the most interesting restaurants in Beijing is in the park – the Fangshan Restaurant, which was started after the park became public in 1925 by a cook who had worked in the Qing court. The food is believed to be of the type served in the imperial court. I ate there once and was served so many courses that I was full long before the meal ended.

China’s emperors had the power to confiscate anything they wanted from all over China for their gardens, and Beihai Park today has decorative rocks that were shipped to Beijing from Henan province. The park’s buildings also include art collections, among them a jade jar used by Kublai Khan to store wine and 495 carved steles. The park also has trees that are hundreds of years old.

A calligraphy museum in the park is housed in two halls built in the 1700s.

The shallow lake is a popular place for boating in the summer and ice skating in the winter.

A snow fall in Beijing is an occasion to head for Beihai Park to enjoy snowball fights and building snowmen.

Zhongnanhai

The two other seas that originally were part of the Western Garden, Zhonghai or Central Sea, and Nanhai or Southern Sea, were garden and palace areas where the emperor carried out government functions while escaping from the summer heat. Zhongnanhai is now separated from the Forbidden City by a north-south road, but it was part of the palace grounds in imperial times. After the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1912, the new Republic of China initially ran the government in Zhongnanhai. After taking power in 1949, the Communist leaders moved into Zhongnanhai and made it their headquarters for China’s top governing bodies – the State Council and the Secretariat and General Office of the ruling Communist Party. The complex has been changed substantially since then, with new office and other buildings having been added.

The closest Chinese equivalent to the U.S. White House, the walled compound contains the two lakes that make up a large part of the compound’s acreage, government buildings and both historic and modern buildings where meetings, conference and banquets are held. Many senior leaders have also lived in the compound over the years, although others live in other parts of Beijing or spend most of their time outside of the city. China has accommodations for senior leaders in many locations throughout the country. As journalists, we stayed in some of these provincial facilities, which tended to be spacious and for the most part well maintained compounds.

Chairman Mao Zedong lived in Zhongnanhai, and Mao’s infamous wife, Jiang Qing, lived there intermittently. China’s last emperor, Puyi, had the Regent Palace built in Zhongnanhai before his abdication, and Zhou Enlai, China’s premier in the 1950s-1970s, lived in a hall in the palace’s west garden. China’s leaders often held diplomatic meetings and state banquets with foreign leaders and delegations in the garden, and probably still do.

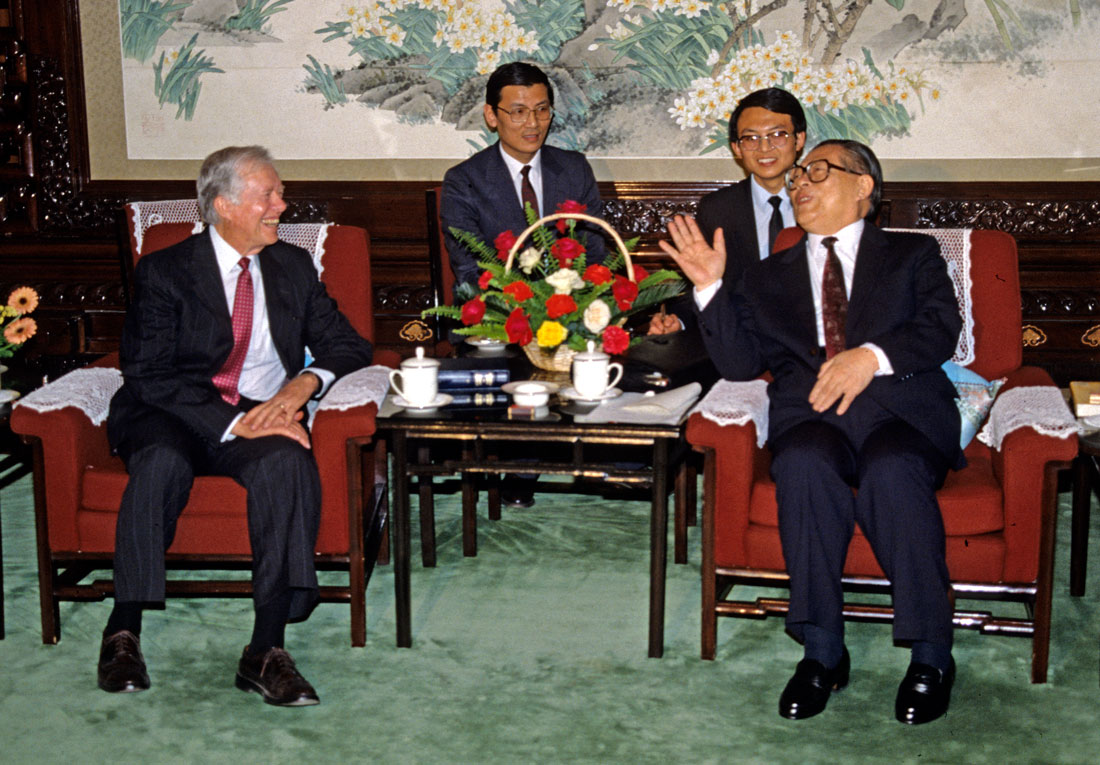

Parts of Zhongnanhai, in the Southern Sea area, including Yingtai Island, Yinian Hall and the Chrysanthemum Study (Chairman Mao's former residence), were open to the public during important holidays and weekends between 1977 and 1985. However, Zhongnanhai is not open to the public now. That doesn’t mean that it is as secretive as some accounts have claimed. Government officials who work outside the compound attend events there, foreign leaders have met frequently with Chinese officials there, and many journalists both foreign and Chinese have enter the compound over the years to cover government and party events. When my husband and I worked as journalists in Beijing, we often went to Zhongnanhai for meetings between foreign and Chinese leaders which were held in a traditional Chinese hall called the Ziguang Ge or Purple Light Pavilion. This two-story traditional Chinese building has been used for diplomatic meetings at least since the Qing Emperor Tongzhi met the envoys of Japan, Russia, the United States, France, the Netherlands and Britain there to accept their diplomatic credentials.

Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter and Chinese Communist Party Secretary Jiang Zemin at Ziguangge in the 1990s.

We also visited Mao’s former study in Zhongnanhai once as part of a journalists’ tour. We were allowed to take exterior photographs of traditional Chinese buildings in Zhongnanhai, but not to photograph the study’s interior. Mao was known for working on a large bed with books and papers piled all around him, and the bed still had books piled on it when we saw it.

Here are some of photos we were allowed to take:

Former Chinese Premier Li Peng with his entourage at Zhongnanhai.

Another historic hall in Zhongnanhai is the Ten Thousand Benevolence Hall or Wanshandian, built by devout Buddhist emperor Shunzhi for a famous monk. Behind the hall is a domed hall and seven-story pagoda. West of it is a Water Cloud Pavilion (Shuiyunxie) that is over the water. Another major building is Huairen Hall, where major State Council conferences have been held.

Major buildings in the Southern Sea area are centered on Yingtai Island. During the reigns of Emperor Shunzhi and Kangxi (1654-1722), seven palaces and nineteen other buildings were constructed on the island. A stone bridge connects the island to the shore. The core building of Yingtai is Hanyuan Palace, where imperial banquets and entertainment were held. After the 1898 failure of a modernization program called the Hundred Days' Reform that was backed by Emperor Guangxu, the Empress Dowager Cixi had Guangxu imprisoned on Yingtai Island. Banquets and receptions now are held on the island.

A number of people who have lived and worked in Zhongnanhai have written accounts of life inside the compound. Former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s daughter Deng Rong wrote extensively about her father’s work as a senior leader in Zhongnanhai before 1966 and her family’s life in a traditional courtyard house on a lane in the compound. Other senior leaders, some of whom were close friends of her family, lived on the same lane. Deng Rong wrote of her immense shock when, during a period when her father was purged from his government position, she witnessed poverty outside of Zhongnanhai for the first time. When Deng later became China’s top leader, he lived in quarters not far from but outside Zhongnanhai.

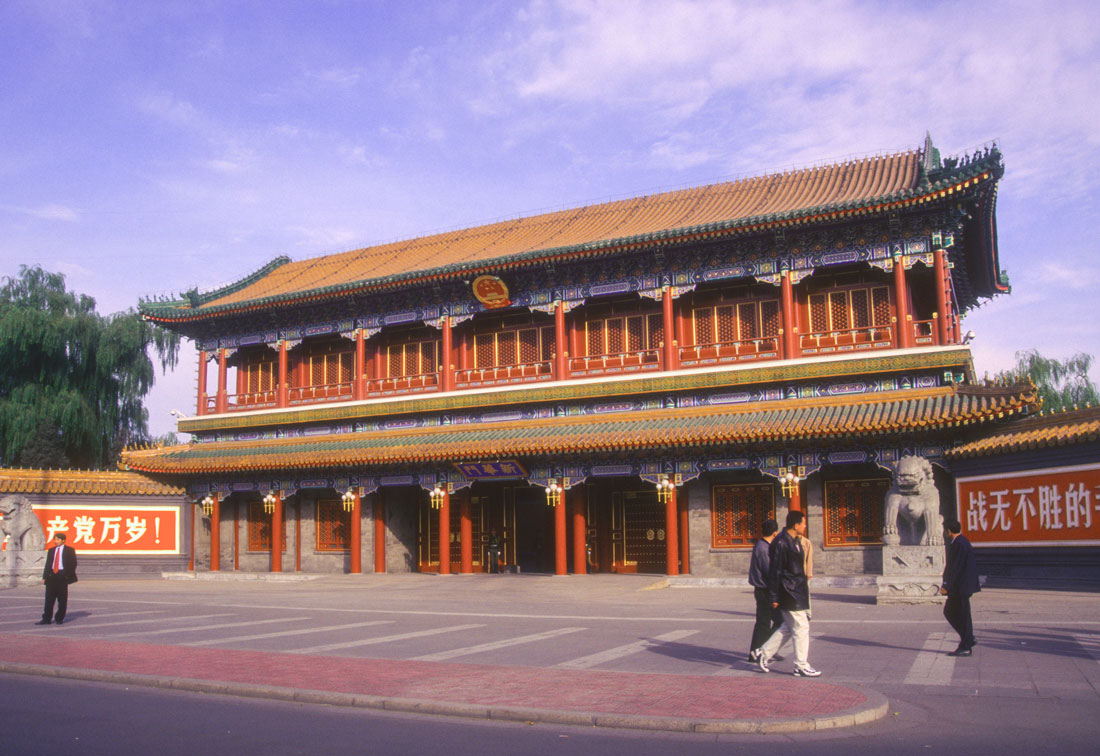

Xinhua Gate, the main gate of the compound and its public face, was built by the early 20th century general Yuan Shikai, the president of the Republic of China after the fall of the Qing Dynasty. Yuan fell from grace when he tried to declare himself emperor and launch a new dynasty. The imposing gate, with its guards and white stone carved lions, has periodically been the site of protests over the years, including sit-ins by Chinese pro-democracy students during the Tiananmen protests of 1989. Protesters camped out in front of the headquarters and even hung their laundry in front of it. We never entered the compound through Xinhua Gate, as we always went through a western side gate to cover events. The gate is about 500 meters west of Tiananmen Square.

Shichahai

North of Beihai Park is another park that was once closely connected with the Forbidden City – Shichahai. This historic area also has three lakes – Qianhai, Xihai and Houhai. It originally was built in the Jin Dynasty. From the Yuan Dynasty on, this area was the northernmost terminal of the Grand Canal that stretched from Hangzhou to the south to Beijing. The Grand Canal’s boat traffic supplied the capital with grain and other essential goods from the rich breadbasket regions of China. During this era, the Shichahai area was the city’s most important commercial district. Today it still has famous Taoist and Buddhist temples as well as former royal mansions and gardens, the most well known of which are the Prince Gong Mansion and the Prince Chun Mansion.

Jingshan Park

North of the Forbidden City is another former imperial park, the focus of which is the manmade hill Jingshan or Prospect Hill. The hill was built early in the Ming Dynasty using soil excavated from forming the Forbidden City moats and nearby canals. Jingshan has five peaks, with a pavilion on each peak. The pavilions once were used by imperial officials for gatherings and leisure, but the park is open to the public now.

Chinese feng shui principles generally held that residences should be sited south of a hill to protect from harmful influences from the north and from cold northern winds. The hill was created to provide the Forbidden City with this protection. It is sometimes called Coal Hill, supposedly because coal for the palaces was once stored at the foot of the hill.

The final ruler of the Ming dynasty, the Chengzhen emperor, committed suicide by hanging himself from a tree on Jingshan Hill in 1644 after Beijing was overrun by rebel forces led by Li Zicheng. Li only held the palace for about a month before fleeing from invading Manchu forces from the north conquered China and established the Qing dynasty.

The palace moat separates Jingshan from the Forbidden City. Until 1928, the park was accessible on the south only from the Forbidden City via Shenwu Gate. However, a street was built north of the moat in 1928 which separated Jingshan Hill from the Forbidden City. The gate thus became the Forbidden City’s back door. The front gate of Jingshan Park is on the north side of the road.

Jingshan Hill is the highest natural point in Beijing and provides a panoramic view of the Forbidden City to the south and the Bell and Drum Towers to the north from Wanchun Pavilion, the central pavilion. Beihai Park and Miaoying Temple can be seen to the west. On a clear day, it is possible to see a panoramic view of the Forbidden City from Jingshan while on a smoggy day, the golden roofs are almost obscured.

During the Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties, fruit trees were planted on the hill. Members of the royal families also hunted there. Entering the park’s front gate, visitors see the Qiwang Pavilion, where emperors worshipped Confucius’ memorial tablet.

Each of the five pavilions on the peaks in the park originally had a copper Buddha statue that represented one of the five tastes – sour, bitter, sweet, acrid and salt, but they were taken during the 1900 invasion of Beijing by Western military forces.

On the north side of Jingshan Hill is a hall where Qing emperors paid their respects to their ancestors and to the east is a hall where the dead bodies of past emperors and queens were placed.

The park has the largest peony garden in Beijing, with some 200 varieties that bloom in May.

Imperial Ancestral Temple

South of the Forbidden City are the Imperial Ancestral Temple on the east and Zhongzhan Park on the west. The Imperial Ancestral Temple is where the emperor led sacrificial ceremonies during annual festivals to honor imperial ancestors.

The tradition that an Imperial Ancestral Temple should be located south east of the palace and a place for the emperor to pray for the nation should be on the southwest was ancient in Chinese palace construction. The Beijing configuration was expressly created to adhere to this tradition and in fact conforms to it more closely than a number of other older palaces did.

The temple has three large walled courtyards. The main hall in the temple, the Hall for Worship of Ancestors, is one of just four traditional buildings in Beijing that stand on a three-tiered platform. Tablets of emperors and empresses were displayed there, along with incense burners and offerings. In front of this hall are two worship halls for princes and courtiers. The western one housed memorial tablets of meritorious courtiers, while the eastern one honored princes of the Ming and Qing dynasties.

Other halls were used to store imperial ancestral tablets and for other functions.

Today, the temple is a public park known as the Working People’s Cultural Palace. It was built in 1420 and has been renovated many times since. The most controversial was in 1736 during the reign of Emperor Yongzheng, when he increased the relative importance of the temple in the state ideology to shore up his disputed claim to the throne.

The Imperial Ancestral Temple is one of the best preserved Ming buildings in Beijing. The temple grounds are famous for their cypress trees, which are several hundred years old.

Zhongshan Park

Zhongshan Park southwest of the Forbidden City is where the Altar for Land and Grain was constructed in 1421. This was the altar where the emperor prayed and gave offerings for a good harvest, a paramount concern in the vast Chinese empire which was dependent for stability on the grain harvest. The park is on the site of a 10th century temple, none of which remains. However, some of the cypress trees in the park are said to date from that era.

In 1925, revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen (Sun Zhongshan in Mandarin Chinese) died in Beijing and his body lay in state in the temple’s main hall. The park was named after him in 1928. A statue of Sun is in a central location in the park.

Zhongshan Park has shaded lanes and quiet spaces, as well as bumper cars and paddle boats to rent. Also in the park is the Forbidden City Concert Hall, which was once the city’s premier concert venue and still is used for music events. In this photo of the park, Beijing residents napped on the benches of a covered corridor on a warm summer day.

Tiananmen Square

South of the two temples is Tiananmen Square, which originally was a long corridor called the Corridor of a Thousand Steps along which were the offices of imperial ministries. The corridor connected the main gates of the Forbidden City to the main gate of the city along what was called the Imperial Way.

The Communist government converted the corridor and surrounding buildings to the world's largest city square in the 1950s.

Along the Walls

Although the sidewalks outside walls of the Forbidden City are not parks, some sections are treelined areas where Beijing residents enjoy strolling.

Check out these related items

The Summer Palace

The Summer Palace, the most famous and heartbreaking of China's glorious imperial gardens, highlights dilemmas in the nation’s past.

Treasure Room and Two Palaces

In the French palace at Fontainebleau is a treasure room of dazzling artifacts taken by the French army from a palace in Beijing.

Tiananmen Square

China's Oct. 1 celebration of 70 years of Communist rule centers on Tiananmen Square, one of the world’s most controversial places.

Ancient Silk Road Meets High Tech

The International Dunhuang Project digitizes old documents, caves and artifacts to enable global study of Central Asian history.

Qing Ming Painting Resonates Over Centuries

China's most famous painting captured traditional life, the traces of which have survived into modern times.

China’s Export Porcelain

Chinese porcelain is durable and branded with its history, so it is used to trace China’s trade and cultural ties with other nations.