Comeback of the Courtyard House

Photos by Forrest Anderson

“If your ceiling should fall, then you have lost a room, but gained a courtyard.

— Alexander McCall Smith

As the ceiling of extroverted modern life has fallen amid the COVID-19 pandemic and the soaring cost of housing, our relationship with our homes has changed.

We have had to create new indoor spaces for study, work and exercise as well as safe, healthy outdoor spaces. Home builders are creating and advertising these spaces to potential buyers. Some of these features hark back to interior courtyards around which homes were built for millennia but which disappeared worldwide during the 20th century.

The home improvement site Houzz has reported an increase in searches related to interior courtyards and has suggested that more houses will be built with such connections to the outdoors in the future. Pinterest is awash with photos of homes with small courtyards.

Many people’s backyards have become courtyards as they have built detached offices or multi-generational housing in them. New homes have interior courtyards or walled back yards accessible from rooms grouped around them. Such courtyards are designed for exercise, play, gatherings, outdoor classrooms and remote work spaces.

Typically, they have plants, flowers, trees, benches and tables and chairs. Some have water features such as fountains, ponds, small swimming pools even in narrow spaces, raised garden beds and paths between rooms or buildings adjacent to them.

I’m delighted by this trend. As a child, my favorite fantasy was to live in a traditional hacienda with rooms around a courtyard. I later spent 14 years in Asia, where I was enchanted by traditional courtyard homes of China and Taiwan and by homes in Japan that had small viewing gardens. Not long before the pandemic broke out, we built a multi-generational house with two living areas with rooms that open out onto a narrow Japanese garden. It has been a haven and a joy as we have worked and lived at home during the pandemic.

Advantages of Homes Built At Least Partially Around Private Courtyards

- Exposure to nature - Ever-mounting mental health research indicates that spending time immersed in even a modest amount of nature boosts moods, eases anxiety and restores emotional equilibrium. Safe natural spaces such as courtyards are more important in stressful times when people need private outdoor areas away from potential security or pandemic threats. A courtyard is a natural backdrop that enhances everyday living. It enables people to enjoy the seasons – flowers in spring, green foliage in summer and snow in winter. If residents don’t have time to grow or maintain many plants, a few in pots along with rocks do the trick. A courtyard provides children with needed outdoor space to play, adults with a place to relax and exercise at home, and seniors with a safe, comfortable environment to experience nature. Residents can socialize in a courtyard but live privately in rooms around it.

- Privacy – As more people live in urban and suburban environments with higher population density, privacy is hard to come by. A small courtyard physically increases the distance between interior spaces, making home offices, bedrooms, fitness spaces and multi-generational sections of a home feel separate from each other.

- Maximizing daylight – Courtyards can help brighten up interior space on a small lot where much of the space is not adjacent to a window.

- Physical and visual connections between indoor and outdoor spaces – A courtyard house has seamless transitions from various rooms between indoors and the courtyard garden, which functionally expands each room that adjoins it. The kitchen can connect to a kitchen garden of raised bed or pots of herbs and vegetables in the courtyard. The living room can be expanded by opening doors to the courtyard. An office or bedroom feels more spacious when it is adjacent to a courtyard. A courtyard can be used for different functions during the day – yoga in the morning, children playing in the afternoon, dinner in the evening. We have found that our house has an almost magical ability to expand or contract as needed. We can accommodate a crowd by opening doors to the courtyard, but the various rooms shrink and become intimate and private when few people are at home and are engaged in solitary activities.

- Energy conservation - Courtyard houses can lower a house’s temperature, saving on summer energy bills, and a courtyard floods spaces with light that helps with energy savings. Courtyard houses allow cross breezes to expel heat in the summer through passive ventilation while the building shades internal windows. In the winter, sunlight is allowed in and surrounding walls block cold winds. Courtyard houses can be divided into zones that can be heated and cooled separately depending on what areas are being used.

- Adding an extension to a home - You can separate old and new sections of a home with a courtyard, avoiding damaging an existing structure when adding on to it. You can stay in the home while building, saving the cost of relocation.

- Education - Courtyards can be so useful as classroom and study spaces for children and college students that they are becoming a required element for some new educational facilities as a result of the pandemic.

- Security - The main rooms of a courtyard house open onto the courtyard while exterior walls may have smaller windows, so that they can be more secure.

- Versatility - Courtyard houses work with any style of building and a small or narrow lot. Our garden is long and thin, with rooms opening to it along one side, because our lot is narrow. Courtyard houses also are a way to use irregularly shaped lots because the courtyard can absorb the irregularity.

On the down side, the build cost of a courtyard house can be somewhat higher because of increased exterior wall area and circulation space. It also is important to design a courtyard house so that the size, orientation and proportions of the courtyard allow for good sun exposure in winter.

The History of Courtyard Houses

Courtyard houses have played a major global role in housing historically, especially in urban environments.

The first courtyard houses appeared in about 6400 B.C. in the central Jordan Valley. Historic evidence of courtyards can be found at sites of the city of Ur, Sumeria, and in the Indus Valley.

Courtyard architecture spread from the Middle East to Europe and took the form of the agora in Greece, the forums and atriums of Rome, the patios of Spain and courtyards of Tudor homes of Britain. On a larger scale, public squares and courtyards within public buildings were popular.

Spanish courtyard houses spread to Latin America, where the hacienda became ubiquitous. Small courtyards with viewing gardens were popular in urban Japan.

The courtyard house was a source of inspiration for Renaissance architects and more recently for architects such as Le Corbusier.

Many African cultures built courtyard houses with adobe and stone, which were cool in hot climates. Some, such as the Ashanti people, decorated their houses distinctively. Almost all of their dwellings have disappeared, but contemporary architects continue to build courtyard houses inspired by dwellings in pre-colonial African cities such as Timbuktu.

In China, courtyard houses date back to at least 3000 B.C. and became the foundation for Chinese architecture from ordinary homes to palaces, temples and government buildings.

Different forms of courtyard houses were a result of environmental practicalities and social and cultural influences. Courtyards have been used to keep animals and for essential activities like cooking, washing, drying and food storage; leisure activities like sleeping, gathering or socializing; celebration of festivals and other family occasions; playing and landscaping. Many religious and educational buildings have garden courtyards.

In the past century, courtyard houses have been neglected in favor of multi-story apartment buildings and dwellings surrounded by landscaping. Many urban dwellers worldwide experience traditional courtyard architecture only at historical and cultural sites. However, some architects have recently begun to use them as a way to solve problems of dense inner city housing. Some are taking a new look at traditional texts describing principles for designing courtyard houses.

This courtyard structure at Ritan Park in Beijing, China, provides a fantasy version of traditional Chinese courtyard houses for tourists. It houses a restaurant.

If courtyard houses are so functional, why did modern societies move away from building them?

To answer this question, let’s look at one of the most interesting examples – Chinese courtyard houses, as China’s move away from them has been dramatic although it has followed global trends. It has spawned major debates about urban planning.

Courtyard houses, called siheyuan or four-sided gardens in China, were ubiquitous for thousands of years in many regions of China until the 1980s and 1990s. They were particularly characteristic of the Chinese capital, Beijing, and other northeastern cities. After the Mongolian conquest of China in 1271, the Mongolians were determined to rule China as Chinese emperors. They built Beijing as their capital with rows of Chinese-style courtyard houses divided by narrow lanes called hutongs. The word hutong is believed to hark back either to a Mongolian word that means the space between Mongolian yurts or to refer to neighborhood wells in courtyard neighborhoods.

The subsequent Ming and Qing dynasties built on the hutong foundation and used the same principles to demonstrate that their capital complied with traditional Chinese notions of architecture, so the city came to look like a checkerboard of courtyard houses lined up neatly along the lanes and streets. The Chinese siheyuan, the fundamental template for traditional Chinese architecture, became a cultural symbol of Beijing. It was used at varying scales for the emperor’s palace, temples, aristocratic mansions and ordinary houses.

The undulating roofs of a Beijing hutong neighborhood.

The ideal siheyuan had a main house on the north of the courtyard facing the courtyard so that it could receive sunlight in the winter. There were buildings on the east, west and south around the courtyard and a decorative entrance gate on the southeast that was the demarcation point between public and private space and reflected the owner’s wealth and social status.

The northern main building was the living quarters of the male head of a family. His wife’s quarters would be in the eastern part of this building and his concubine, if he had one, would live in the western section. His sons and their families would live in buildings along the eastern and western sides of the courtyard. In the south was a reception hall for guests that doubled as a study and servants’ quarters. Unmarried daughters and female servants lived in a building behind the main building. The courtyard typically had flowering and fruit trees, flower beds, sometimes room for a vegetable garden and a water feature that collected rain water.

The courtyard served as a place for socializing in the family and with friends and neighbors, conducting family chores and holding family events such as birth celebrations, marriages, funerals and annual festivals. All of these activities were circumscribed by customs and rituals. The curved eaves of tiled roofs allowed rainwater to flow off the buildings, provided shade in summer and retained warmth in winter. In northeastern China, courtyards were large and broad to increase sunlight exposure. In the south, houses had multiple stories to increase shade in the courtyards.

Courtyard houses provided families with private oases, a space naturally cooled by trees, plants and water elements, and security. Courtyards were a safe play space for children, who were watched by grandmothers.

Traditional courtyard houses were places for multiple generations of people to gather.

The ability to withdraw into a safe inner world is an important part of Chinese and many other cultures. Poise and inner calm, exemplified by Daoism, were embodied in courtyard houses. Confucianism, China’s other prevailing philosophy, contributed to norms of social behavior that can be observed in courtyard architecture - respect for older generations, a hierarchical order in families and society, and symmetry and balance.

Neighbors, whose houses shared walls, were a vital part of life in a courtyard neighborhood. Children played in each other’s courtyards and neighbors gathered daily to chat, play Chinese chess or do household chores such as knitting or patching clothing in courtyards. Outside in the lanes, neighborhood life was vibrant. People had small shops, stands or restaurants in the lanes, there were vegetable markets along them, and people socialized.

Neighbors in a Chinese courtyard house.

The system proved remarkably stable. When we lived in Beijing, we knew people whose families had lived in the same courtyard house for more than 300 years.

However, the age-old siheyuan system had begun to break down shortly after China’s last imperial dynasty fell in 1912. Beijing was subjected to a dizzying array of competing warlords, governments, Japanese occupation in World War II and a subsequent civil war. The beautiful courtyard houses deteriorated. The city’s population burgeoned and people crowded into rented space in courtyard houses, a process described in Lao She’s famous novel about Beijing, Rickshaw Boy.

By the time the Communists rose to power in 1949, many courtyard houses were run down. Communist leader Mao Zedong and other top officials moved into courtyard houses in a garden west of the imperial palace called Zhongnanhai, but they had little respect for traditional Chinese architecture. Mao considered the siheyuan a remnant of feudalism, and deprioritized housing for the burgeoning urban population in the interest of funding large scale industrialization. New housing was mostly Soviet-style apartment blocks.

Mao saw the breakdown of the siheyuan system as a way to break the power of multi-generational Confucian families which he decried as oppressive. During the 1960s, he converted homes to public ownership and forced courtyard home dwellers to vacate rooms so unrelated families could move into them. Courtyards were built out with makeshift dwellings to accommodate more people.

This photo shows the makeshift structures built into a traditional Chinese courtyard.

Mao’s Red Guards roamed through hutong neighborhoods, raiding homes and looting or destroying beautiful carvings, paintings, porcelain, furniture and other vestiges of traditional life. Social relations between inhabitants of the crowded courtyards were poisoned when some residents reported to authorities the behavior or remarks of their neighbors. In many cases, the consequences were severe, resulting in severe beatings, imprisonment or other punishments for those who had been singled out. Even high officials were not exempt. When they were purged, many lost their courtyard housing and were sent to prison or labor camps.

Ordinary courtyard houses had no indoor plumbing or bathing facilities, so residents used public neighborhood toilets and bathhouses and hauled water from neighborhood taps. Roofs leaked and many siheyuan had faulty wiring that made them dangerous fire traps. Cooking was done on smoky charcoal stoves, often in kitchens shared by multiple families.

By the time Mao died in 1976, many siheyuan were in shambles and China had a housing shortage so critical that members of families had to sleep in turns or at work. China’s new leaders launched capitalist-style economic reforms that in the 1980s and 1990s created a booming commercial real estate market and turned Beijing and other cities into massive construction zones.

In the 1990s, old courtyard houses and neighborhoods were systematically demolished and replaced by commercial high rises. In the early 1950s, Beijing’s inner city had 11 square kilometers of single-story siheyuan. By 2005, only three square kilometers has survived.

A woman sitting in her demolished neighborhood, Xi'an, China.

Residents of siheyuan were moved to apartment buildings, often hours from the city neighborhoods where their ancestors had lived for hundreds of years. Long-standing community ties were disrupted and many people were forced to commute for four hours a day to work or school. Transportation facilities were inadequate, so people had to stand in line for hours to get on a bus. The suburbs had substandard educational, health care and work options.

Man sifts through debris to salvage items from a demolished hutong near an apartment building, Beijing, China.

These residents of a demolished courtyard neighborhood were the last of a family line that had lived there for 300 years.

Courtyard residents moving away as their hutong homes were demolished.

Relocation-related disputes became a serious social issue. People who fought forced evictions were jailed and their lawyers threatened by government officials. Some residents killed themselves rather than be relocated. There were self immolations.

Critics were angry over the 2012 demolition of famous courtyard houses such as that once owned by Liang Sicheng and his wife Lin Huiyin, who were seen as leading preservationists of Chinese traditional culture. Liang wrote The History of Chinese Architecture and designed the Monument to the People’ Heroes that stands in Tiananmen Square. He tried to persuade Mao Zedong to save Beijing’s city walls which encircled the capital, but Mao replaced them with a ring road. Liang wanted to establish a new capital outside of Beijing so Beijing’s architecture could be preserved.

A few historic neighborhoods in the city’s center have survived, protected since 2002 as historic districts to conserve the traditional character of the area around the Forbidden City and other historical sites. These areas have gentrified, with some siheyuan purchased by foreigners or wealthy Chinese and renovated with modern amenities. Prices of sihehyuan have soared, and, depending on the area, can sell for millions of dollars.

Some hutong neighborhoods have been renovated by hotel chains and now are hotels, while some 500 courtyard houses once owned by famous people have been preserved as museums and other cultural sites. Some residents worry that these neighborhoods are internationalizing with boutiques that sell Parisian fashions and international restaurants.

Following global trends, the family structure in China has changed dramatically since most Chinese lived as extended families in courtyard houses. Family size dropped dramatically as a result of the 35-year state-imposed one-child policy introduced in 1978 and phased out in 2015. The traditional extended family household was replaced by nuclear families of 1-3 people in which family life revolves around a couple’s financial independence, privacy and pursuit of personal goals. This change has had major implications for new housing designs as has the increasing cost of housing.

China, like many other areas of the world, is not going to return to the larger traditional courtyard houses of China’s past. They are far too large and expensive for today’s average family. This poses a problem for modern architects tasked with renovating and preserving historic neighborhoods to retain Beijing’s cultural ambience.

From the lanes, these neighborhoods look traditional, but years of subdividing and rebuilding the spaces behind the walls have broken down the courtyard structures. The result is delapidated, chaotic rabbit warrens and irregular spaces, as can be seen on satellite maps.

Some attempts to renovate courtyards with modern apartments around communal courtyards were only partially successful, with the courtyards between some apartments ending up being used for bicycle parking and spaces to hang laundry or pile debris.

An early attempt to build new housing that preserved the cultural atmosphere of the hutong neighborhoods, Beijing, China.

Some Chinese architects are taking a different tack to historical conservation which combines the look and feel of courtyard homes with modern small single- or double-story apartments, each with a small private courtyard. With this approach, the neighborhoods look like traditional siheyuan and retain the feel of living in a hutong neighborhood with all of the convenience that that implies. However, the internal structure accommodates the modern housing needs of small families.

This approach checks the boxes of urban housing that addresses small family size, provides privacy needed in a pandemic era, helps satisfy the need for more trees to lessen the climate consequences of high-rise urban heat islands, assists with efficient energy use and preserves local culture and history.

Another ancient capital that does this well is Kyoto, the old imperial capital of Japan, which abounds in old hutong-like walled lanes. Houses on these streets have small private courtyards with trees and decorative gates that give the city a garden-like atmosphere, provide families with a private piece of nature and preserve an important historical location's cultural and historic character while providing modern amenities.

Decorative gates into private courtyard gardens abound in Kyoto.

More photos of Chinese housing

More photos of Kyoto

Check out these related items

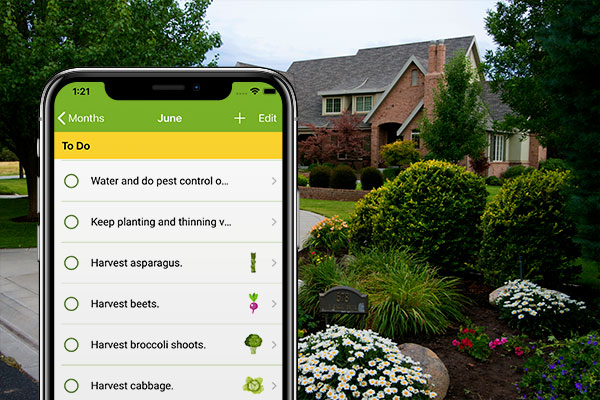

Green Thumbometer App

The all-in-one iOS app that's a gardening calendar, gardening journal, gardening to-do list and source of gardening information.

Home Gnome App

The iOS app that helps you keep track of what tasks you need to do and when to do them to maintain your home well all year long.

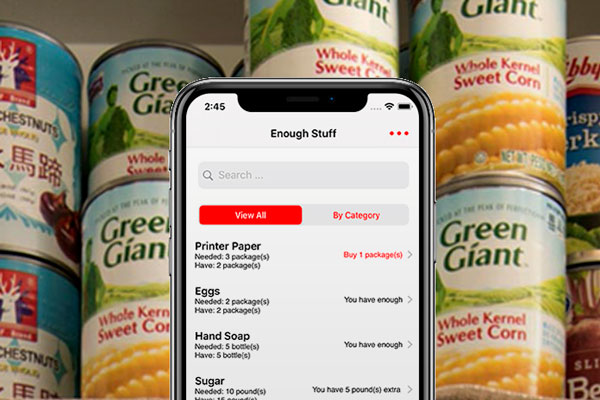

Enough Stuff App

The Enough Stuff inventory app for iOS helps you keep track of how much you have of items so you don't buy more of them than you need.

A Classical Chinese Garden

Lan Su Chinese Garden in Portland, Ore., was built by artisans from the garden city of Suzhou, China, to demonstrate the basic elements of Chinese gardens.

China’s Walled Cities

Only scattered remnants survive of the many walled cities that once defined the Chinese empire.

Elements of a Japanese Garden

Imagine you're sitting in Los Angeles traffic on a hot day. Take a break and head for a cool green oasis - Suihoen Japanese Garden

Japanese Design Past and Present

Architect Kengo Kuma's village at the Portland Japanese Garden blends modern architecture with traditional Japanese design.

Green thumb challenged? Grow rocks

Okay, so you don’t have green thumbs. We don't either. Not to worry. Rock gardens are the next best option.

Making a Japanese Gate

We were charmed by the beautiful gates that are the entrance to homes in Kyoto and Nara, Japan, so we decided to make our own.