How to Read Stained Glass Windows

Photos by Forrest Anderson

Amid the political tumult of the past two years, a number of American churches have quietly removed historical stained glass windows from chapels and replaced them with new ones deemed more in line with current social views.

This raises the question of how stained glass windows acquired meanings beyond simply expressing religious devotion and providing beautiful multi-colored light?

I went looking for the answer to this question and was surprised to find that the answer is “just about as soon as stained glass windows came into being.”

The reason is that stained glass windows lend themselves admirably to imparting a message to those who view them. In medieval times, that meant parishioners of a church who attended services at a church at least weekly and on major feast days. For almost a millennia, stained glass windows have been a powerful medium used by kings, rulers and other public figures to get across a dual message of their authority to rule and by clergy to instruct the faithful in religious history, symbolism and doctrine.

A concerted effort was made to link kings and rulers with religious ideology, as in this stained glass window and statue at Saint Eustache, Paris, France.

Stained glass windows are strongly associated with Gothic architecture and medieval Christianity. However, they also have long been used in mosques and Jewish synagogues although generally with geometric or decorative motifs rather than the human figures used in Christian churches.

What is Stained Glass?

Stained glass dates back thousands of years. It was produced in the 11th century BC in the Assyrian city of Ninevah. Small colored glass items such as bottles were made by the Egyptians and Romans.

In early Christian churches of the 4th and 5th centuries, many windows were filled with ornate patterns of thinly-sliced translucent alabaster stone set into wooden frames. Evidence of stained-glass windows in churches and monasteries in Britain can be found as early as the 7th century. The use of stained glass in windows became popular about 1,000 years ago, mainly in religious buildings.

In the Middle East, Syria had major colored glass manufacturing centers. Stained glass in Europe reached its height in the Middle Ages as a format to illustrate the Bible for a largely illiterate population.

Stained glass is created by combining sand and potash at temperatures of almost 3000 degrees. While the glass is still molten, it is colored by adding small amounts of metallic oxide powders.

Small pieces of hand-blown glass were flattened into sheets. After they had cooled, an artisan would lay the pieces onto a design and crack the glass with a hot iron into rough approximations of the sizes needed. The rough edges would be refined using an iron tool to carefully chip away excess glass until the shape needed for a composition was achieved. The pieces were arranged to form patterns or pictures that were held together by strips of lead and then supported by rigid frames.

Early simple pictures made in this way eventually became more complex as new techniques were developed to control stained glass and make more intricate, painter-like designs.

Adding copper oxides to the glass makes green glass, cobalt makes blue, and gold makes dark red and violet glass. Copper makes bright red glass. Red was a particular challenge to create because the color wouldn’t develop unless the coloring ingredients were concentrated. This created glass that transmitted little light and could appear black. To get around this, glass artisans started creating a thin layer of red that they laminated to a thicker piece of clear or lightly tinted glass. This is called flashed glass. Having figured out how to do this, they started doing it with other colors because the two layers of glass meant that the colored glass could be engraved or abraded away to reveal the clear glass on the other layer. This enabled artisans to create rich details and patterns with intricate creatures, designs and coats of arms. This was the most common technique used to make inscriptions on early medieval glass.

In addition to mixing color in glass, artisans began to add color to the surface of glass and fix it with a light firing in a furnace or kiln. Silver compounds were applied to the surface to make colors ranging from orange-red to yellow. This causes windows to glow gold and when applied to the exterior, gives them some weatherproofing. It also produces green when used on blue glass.

Painting also was applied without firing, but it wasn’t very durable, so little has survived. Instead, an enamel paint was diluted to vary its transparency and mixed with glass that had a low melting point which allowed it to fuse directly onto the glass of the windows. Using semi-transparent enamel paint allowed the creation of shadows and appearance of three dimensions. When it was dry but before firing, a small hog’s hair brush was used to brush out tones for greater realism and detail.

The painters placed a window section on an open easel placed before a window or placed the glass flat onto a transparent table, so the artist could see the effect of light coming through the glass as it was painted. Once the painting of a pane was finished, it was refired to fix the color.

How to Make a Stained Glass Window

Create an accurate template of the window opening that the glass will fit in.

Create a design suitable to the location of the window and the theme of the building as well as the available glass and technical constraints. Often, the artist created a small scale model of a window first to get approval for the design from the patron who was financing it.

Create a full-sized design. In medieval times, this was done directlly on the surface of a white washed table which was used as a pattern for cutting, painting and assembling the window.

Each piece of glass was selected for its color and cut to match a section of the design. By the 17th century, a style of stained glass evolved that wasn’t dependent on such cutting because scenes were painted onto square glass panels like tiles and then fired before the pieces were assembled.

Details were painted onto the glass and refired.

The painted pieces were assembled with metal strips between them and the joints were soldered together. Cement was placed between the glass and lead to make the windows weatherproof.

Gilding and other embellishments were added.

When the windows were mounted, iron rods were placed across them at intervals to help support their weight. The window was tied to them with copper wire.

As Gothic architecture developed and became more ornate, windows were larger and provided more light in buildings. They were supported by stone ribs called tracery.

Creating these amazing windows required both artistic and engineering skills because windows must fit snugly into the space, resist wind and rain and support their own weight. Once in place, however, they were extremely durable as long as they weren’t smashed. Many large stained glass windows have survived for almost 800 years in Europe.

These windows were integrated with high vertical arches and columns of Gothic churches. The circular rose window was developed in France and led to designs of extreme complexity such as the windows at the royal chapel of Sainte-Chapelle in Paris.

Imparting Messages in Stained Glass

Stained glass windows were an environment in which kings and rulers could reinforce for their subjects the ties between them and the concept of divine kingship as well as their own relationship with the immensely powerful Roman Catholic Church. This strategy came to a peak in Sainte-Chapelle and has influenced the use of stained glass windows ever since.

Sainte-Chapelle has by far the largest collection of stained glass windows in the world and played a key role in creating the concept of the nation state.

The story of Sainte-Chapelle began decades before the building was created, when King Philip II launched a building boom in Paris that helped lay the foundation for his grandson, Saint Louis IX’s glittering 13th-century reign. Louis IX’s father died after only three years on the throne, and the strong-minded and religiously devout Blanche of Castille became regent of France. She reined in a variety of fractious rebels and foreign threats to pass a kingdom of relative peace to her son when he came of age.

Blanche was an genius at royal branding who linked her pious son to the universally revered image of Christ and herself to the Virgin Mary in the public’s eye through financing art, including stained glass windows, in cathedrals and churches.

A statue of King Louis IX in Saint-Chapelle.

Sainte-Chapelle was the height of this campaign, spurred on by being offered the chance to buy the most coveted religious relic in Europe – the crown of thorns believed to have been worn by Christ. Louis’ cousin Baldwin II of Constantinople mortgaged the crown to Venetian bankers to pay for the defense of Constantinople, and then offered the crown to Louis in exchange for him paying off the debt.

Louis jumped at the chance. The crown was brought to Paris with great pomp and ceremony, and Louis built a holy chapel in his palace, Sainte-Chapelle, to house the relic and others such as a purported fragment of Christ’s cross. The purchase brought the effort to identify Saint Louis as the royal heir of Christ full circle, because he was now in possession of what was believed to be Christ’s crown.

Louis had the chapel built as a reliquary for the crown and other supposed relics of Christ’s Passion.

The building was intended to drive home the central point that Paris was now the New Jerusalem, a heavenly paradise, and Sainte-Chapelle was its religious center and spiritual throne room. To create this environment, Louis built a sparkling building filled with multi-colored light that brought to mind both the Temple of Solomon and the colored gem-encrusted city of New Jerusalem described in the Bible. The relics were placed in a silver and gold Grand Chassé or chest reminiscent of the Ark of the Covenant that sat at the far end of the chapel in a structure built to look like the porch of Solomon’s temple. The dimensions of the chapel are the same as those for Solomon’s Temple described in the Bible.

This is one of 15 huge stained glass windows composed of 1,113 panels of glass at Sainte Chapelle. Nearly two-thirds of it is original to the 13th century.

The chapel’s 670 square meters of stained glass, not counting the west rose window which was installed later, are the stars of the show. Because much of the supporting structure of the building was in iron bars and columns that were either on the exterior or decoratively painted in gold, red and blue that matches the windows, the chapel appears to be made entirely of glass.

This illusion was made possible by moving the supports of the walls and supporting colonettes to the exterior of the building and supporting the windows with two series of iron bars at mid-height and at the top. The support bars are concealed by stone tracery. Other metal supports for the windows are hidden under the roof eaves.

The iron bars form geometric shapes framing each scene. Because of this complex network of frames, each window panel is small. The windows are dominated by red and blue and filled with figures and scenes, mostly from Biblical history, as well as images of heraldic shields, castles representing the coat of arms of Blanche of Castile, and the royal Fleur de Lis emblems.

The windows of Sainte-Chapelle were primarily devoted to the relics preserved in the chapel and to connecting King Louis IX both with Christ and the kings of the Old Testament. The windows show scenes from the Old Testament and King Louis carrying the crown of Christ in the midst of images depicting the Passion of Christ. One large window also depicts the Apocalpyse at the end of the world in which the resurrected Christ is to return. The message was that Louis was the heir to Christ’s authority.

The windows of Sainte-Chapelle are believed to have been made by three different workshops, with slightly different styles. The styles are echoed in the windows of other 13th century cathedrals and churches that likely were by the same artists. From the perspective of more recent stained glass windows, the Sainte-Chapelle windows are simple and cartoonish. Although the majority of the windows were supposed to show Biblical figures, they are dressed in medieval clothes, with crowns and some with medieval armor.

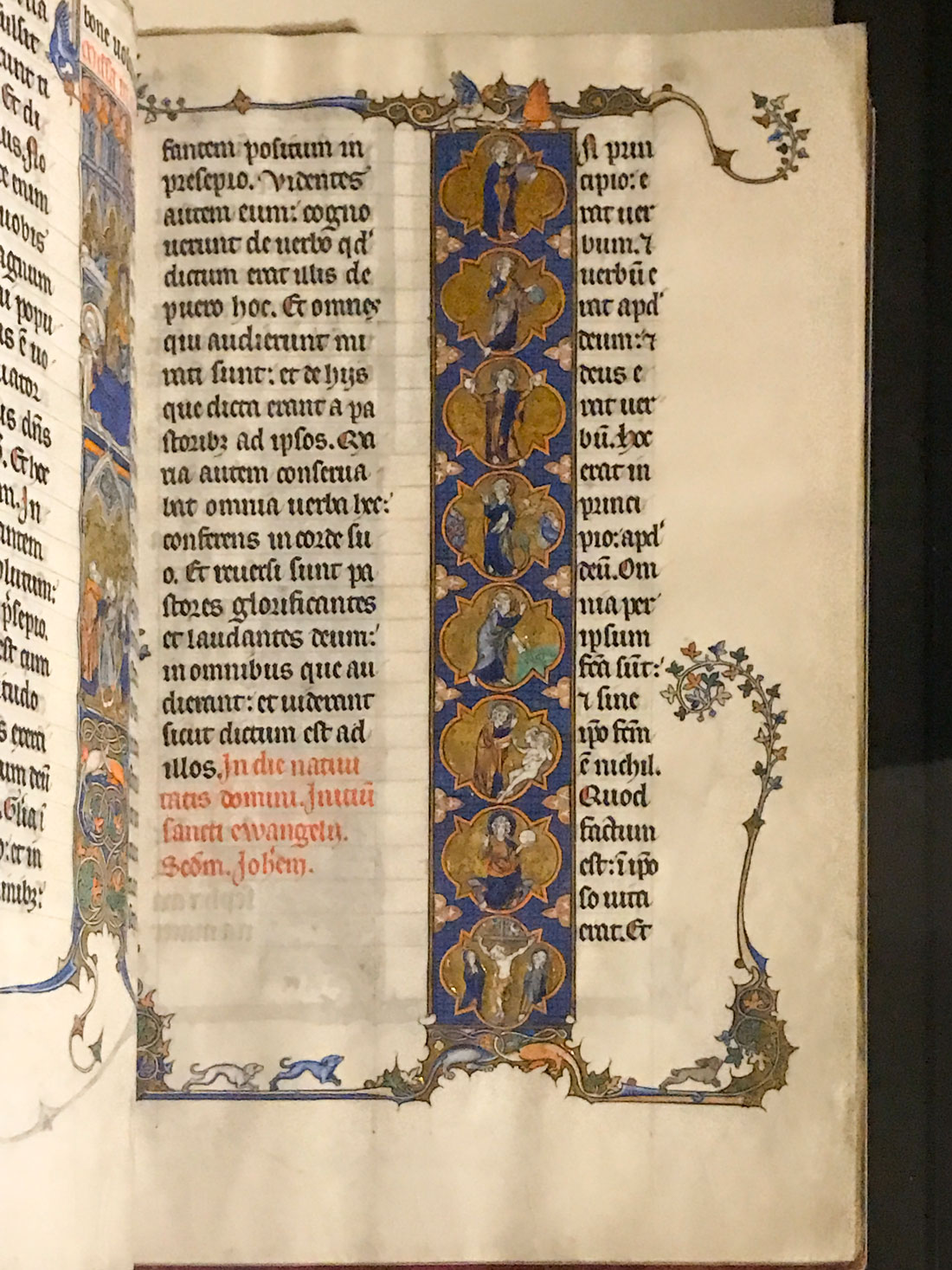

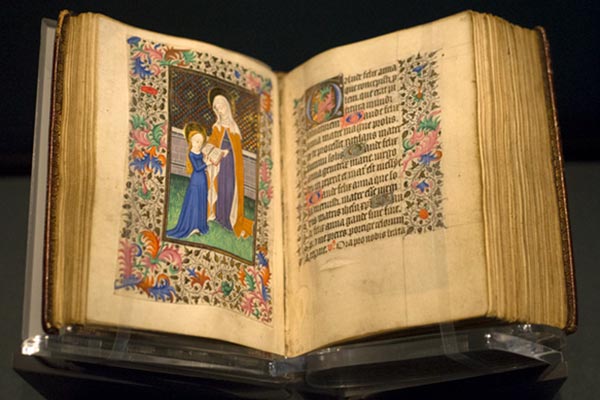

Some of the windows appear to have been influenced by new developments of the time in illuminated manuscripts.

The exterior of the building, which at the time was the tallest building in Paris, has a series of pinnacles reminiscent of the crown to remind the city’s residents of their devout king who possessed Christ’s crown.

Stained Glass Windows in Religious and Political Pageantry

Today, the meticulously restored chapel is a tourist site owned by the French government and has been stripped of its religious role. However, in the British library in London is a gorgeously illuminated 13th century manuscript called a lectionary that was used for religious readings at Sainte-Chapelle. It gives a glimpse of the multimedia extravaganzas that occurred there at Christmas and on other feast days.

On Christmas Eve, Saint Louis’ family and guests would have congregated in their holiday finery in the chapel for midnight mass. The stained glass windows would have been obscured by the darkness, reflecting their colors only in the candlelight as the clergy in full regalia conducted the mass amid the singing of Christmas carols and chants. Incense would have wafted through the air and filled the chapel with a sweet scent, making the experience a multi-sensory immersion. The reading was from the New Testament, Luke 2:1-14, which tells how Joseph and Mary travelled to Bethlehem where Mary gave birth to Jesus in a stable and laid him in a manger while shepherds were visited by an angel who announced Christ’s birth.

After the mass, the clergy and congregation would leave for a few hours of sleep, returning for a second mass at dawn on Christmas Day. The reading continued with Luke 2:15-20, in which the shepherds went to Bethlehem, found the Holy Family and glorified God. As the congregation listened, a weak dawn light would have gradually illuminated the dark corners and high ceilings of the chapel.

A celebratory Third Mass emphasizing Christ as the Savior of humanity, was held later in the day with bright sunshine streaming through the glowing stained-glass windows that depicted scenes from Christ’s Passion. The effect of the three services taken together was symbolic of the birth of Christ illuminating a dark world. After participating in the mass and listening to triumphant Christmas carols, the congregation would have left to partake of sumptuous Christmas feasts in the palace.

The chapel was thus intended not just to be a building for quiet contemplation, but a multi-media and multi-sensory experience that emphasized not just Christ as the Savior of the world, but Saint Louis as his spiritual and secular heir.

The stained glass windows that projected and amplified colored light as well as providing the visual aids for the narrative were a key part of the show in a pre-electricity era, with sunlight filtered through the windows playing a key role in projecting the windows’ message on a large scale. They and the relics bore witness to the congregation of the the tangible reality of the Christian faith and Louis’ devotion to it.

The chapel also had an important secular message that was intimately connected with the events of Louis’s day. The Old Testament scenes were rife with knights in armor fighting against heathens, scenes highly relevant to Louis’s plans to leave with his army on the Seventh Crusade shortly after the building was completed.

The message of Sainte-Chapelle spread throughout churches and cathedrals in France and elsewhere in Europe through stained glass windows, statues and paintings. Louis’s descendants also intermarried with royalty and nobility throughout Europe and built their own Sainte-Chapelles to help spread the prestige of his brand. Depictions of Louis, who became the only French king ever canonized as a saint in 1297, went up all over France and still can be seen in many churches.

The branding of a church’s message through its stained glass windows still can be seen in churches all over the world.

Types of Stained Glass Windows

Poor Man’s Bible - Sainte-Chapelle's strategy of a series of stained glass windows that taught people the stories of the Bible is now one of the most common ways in which stained glass windows are used in churches. The viewer can walk from window to window on a journey that takes them through the Old Testament and then through the life of Christ from the New Testament. This is called the poor man’s Bible because the windows originally were a way to teach people the stories of the Bible in a pre-printing era when the language of religion was Latin and most people were illiterate and had no access to a Bible. The windows were visual sermons and visual aids in the on-going rituals of the church. The goal was to show the viewer the way to salvation. This required that the viewer accept the premise that he was a sinful being who would be brought to trial on the Day of Judgment. Christ as not just the judge but the way of salvation and mercy was shown in stained glass windows of his birth, crucifixion, atonement for mankind’s sins and resurrection. Often, scenes of Saints who had received hopeful visions or experienced miracles also were shown in this context.

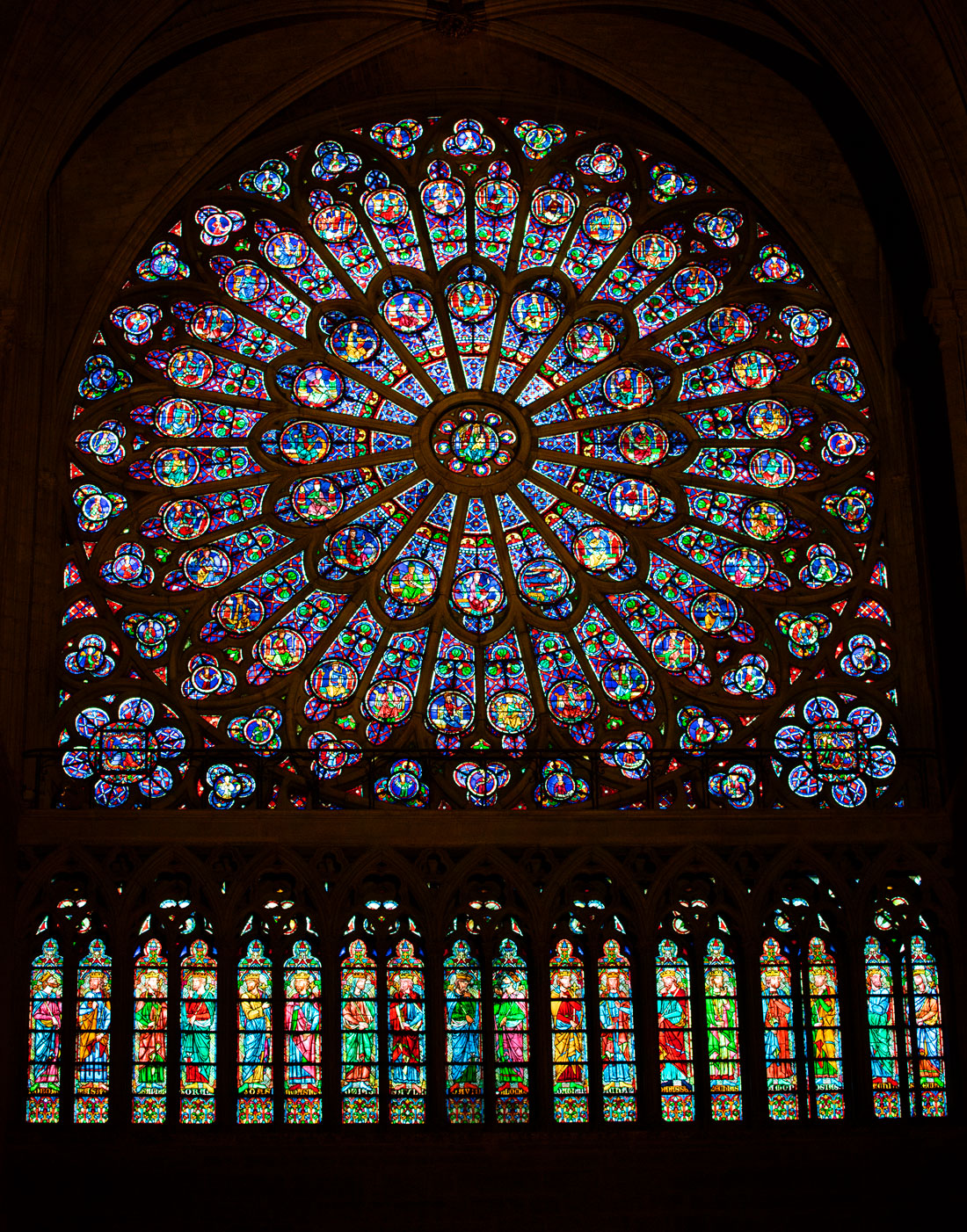

Rose Windows - The two most common styles of stained glass windows for Gothic cathedrals were tall spear-shaped lancet windows and circular rose windows. The origins of rose windows go back to round windows in Roman architecture. Rose windows were made of dozens of panes of glass depicting various scenes and radiating out from a central medallion that commonly identified the window’s theme. The windows actually are segments of glass divided by stone supports that are often ornate. They appear in Gothic-style architecture throughout the world.

The north rose window at Notre Dame, Paris, France. The theme of the window is the life of the Virgin Mary.

Their most common theme is the Last Judgment of Christ in which he is seen seated in the center with apostles, prophets, saints and angels around him. The most famous stained glass windows in the world are the north and south rose windows of Notre Dame, which were sponsored by Louis IX. The south window is one of the world’s largest rose windows, with a diameter of about 43 feet and a New Testament theme. Many rose windows as well as other stained glass windows are dedicated to the Virgin Mary and sections of glass in them revolve around scenes and symbols from her life.

Tree of Jesse – This was a depiction of the ancestors of Christ shown in a branching tree rising from Jesse of Bethlehem, the father of Old Testament King David. The tree was adopted as the subject of many stained glass windows, including one at Sainte-Chapelle and one in Notre Dame. At Sainte Chapelle, it was intended to reinforce Louis’s connection to the Old Testament kings and Christ.

Patrons who paid for the windows – Donors were believed to gain merit from financing windows and are often shown in them with Christ or a saint. Windows were a form of marketing in addition to an expression of devotion. The patrons were frequently pictured in windows that they funded, praying. Craft guilds for bakers, butchers, tanners, furriers and other craftsmen donated windows that showed them at work. Stained glass windows incorporated not just Biblical narratives, but stories from history, literature and mythology. They depicted saints whose relics were stored in a church or who were the church’s patron saint or coats of arms of donors. A version of that is common in American churches when a stained glass window has an inscription in memory of someone whose family paid for the window. Sometimes, windows in American churches include the figures or the names of people who were wealthy slaveowners or Confederate generals. Hence, the recent removal of some of them from churches as the tide of public opinion has turned against the honoring of past slaveowners.

Other themes - A group of windows together can tell a narrative about a building or its locale. As time went on, stained glass windows came to be used in not just religious buildings, but palaces, homes of wealthy people, banks, parliamentary buildings. They often told the story of those buildings or the cities where they were located. A college hall’s windows showed figures representing the arts and sciences. In a home or restaurant, stained glass windows could represent landscapes, animals and plants. Stained glass windows in court or legislative buildings showed scenes from the history of the area or prominent political figures.

In the 14th century, stained glass windows ceased to be mosaics of different colors and came much closer to paintings. This changed the narrative style of windows. Prior to the 13th century, windows were of dozens of scenes from the life of a Saint or martyr, showing all the episodes of his life. In the 14th century, windows began to concentrate on one single important event of the martyr's life at a larger scale.

In the second half of the 15th century, stained glass included the use of perspective and other painterly techniques. The names of stained glass artists became known, and some traveled from city to city to make windows. Windows were made not only for cathedrals but also for town halls and palatial residences. As paper became more common, drawings of prominent windows circulated and the same design could be used in several different cities.

This stained glass window at Saint Gervais-Saint Protais in Paris is like a painting and shows comtemporary fashions and architecture at the time it was created. Stained glass windows are valuable sources of historical and cultural history of the eras in which they were created.

Saint Gervais-Saint Protais Church in Paris, France. Churches were intended to represent the Kingdom of Heaven, and stained glass windows were used to vastly amplify and color sunlight and thus give stone buildings a gem-like feeling of heavenly Paradise as it was described in the Bible.

Every element of the stained glass was rich with Christian symbolism. The walls of glass corresponded with the walls of the celestial city, ornamented with jewels and filled with divine light, as described in the Book of Revelation. A panel of workers with a background or frame of elaborate arches and columns indicated that they were laboring in a celestial workshop. Climbing ivy which surrounded many scenes represented the renewal of the Garden of Eden on earth.

Apostles and saints were portrayed with objects associated with them, so viewers could recognize them. A female figure with a crown represented the church. An angel sheathing a sword represented the angel who guards the gates of paradise or the peace made between God and man by Christ’s sacrifice.

Stained glass windows have had such a powerful symbolic meaning throughout history that political turmoil has been one of the major threats to them.

During the English Civil War in 1642-43, Puritans smashed stained glass windows because they considered them idolatrous graven images. In the French Revolution, windows were smashed or removed because they were considered linked to the authoritarian power of both the monarchy and the vast power of the Catholic Church. In later times, however, stained glass windows were adopted by Protestant churches, many of which also incorporated conventions such as rose windows, Poor Man’s Bible and other similar convensions.

Stained glass windows, like other art forms, have followed style trends such as the Arts and Crafts movement, Art Nouveau and the flora and fauna motifs of American glass manufacturer Louis Comfort Tiffany.

Medieval-style stained glass also has experienced a number of revivals, including a 19th-century one after many churches were damaged in the French Revolution, an early 20th-century one, and a post-World War II one when thousands of churches were restored after having been damaged by bombing. Some windows have been restored using modern manufacturing techniques but in styles original to the church. Other artists have gone in a different direction with abstract stained glass windows created for 20th century modern buildings.

Saint Severin Church in Paris, France, has a combination of traditional stained glass windows and modern abstract ones.

See more photos of France

Check out these related items

Gothic Architecture - Imagining Infinity

Gothic architecture has been called both magnificent and monstrous. We examine why.

Illuminated Manuscripts

Illuminated medieval manuscripts preserved culture and religious beliefs and set a foundation for book design and art styles.

Paris’s Oldest Church Restored

Paris' oldest church, Saint Germain des Prés, is emerging from layers of grime and soot as a meticulous restoration reveals its vibrant color.

The World Mourns Notre Dame

Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris, France's national cathedral, was badly damaged in a fire.

Portraits of Mary

Mary, the mother of Christ, may be the most prominent visual icon in the world. We explore her history.

Saint Sulpice Church - Paris’s Temporary Cathedral

Saint Sulpice Church in Paris has a turbulent history dating to the 7th century. Today, it is Paris's temporary cathedral amidst the pandemic.