The Tiny Wonderland of Netsuke

Photos by Forrest Anderson

One of Japan’s most exquisite art forms developed from a lack of pockets in men’s kimonos and other garments. This raised the perennial dilemma of where a man was to stow his money, writing instruments and seals used in commerce, along with his pipe, tobacco, snacks and other small belongings.

In one of those fascinating twists in which a culture comes to a unique solution to a common problem, the sagemono was born. Sagemono were containers hung by cords from the sashes of kimonos. They included pouches, small baskets, or small "inro" boxes that were held closed by beads on cords. The cords were slipped under the sashes that held kimonos closed and then hooked on the top of them by means of a fastener called a netsuke.

Inro box and netsuke, at the top of the cord. The inro boxes that were used with netsuke generally were about 2 inches wide and 2 1/2 to 4 inches long, with two to five compartments. Silk cords along the length secured by a bead which also could be elaborately carved. The netsuke at the end of the cord hooked to the kimono sash. Inro boxes were elaborately carved and painted or gold lacquered. Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

Netsuke means “attached root,” a reference to the wood from which netsuke originally were created.

The front of the netsuke hid the end of the cord, which hooked to holes in a netsuke, below. Los Angeles County Art Museum. Netsuke are difficult to photograph because they are so tiny, only about an inch tall. They require closeup photography techniques to reveal their details.

Because this was Japan and the Japanese excel at making everyday objects into art masterpieces, netsuke did not just carry on as a functional clothing accessory but developed into elaborately carved miniature works of art.

The tiny items, most about an inch long, are sculptures that represent real and imagined worlds in miniature. They draw on a Japanese and Chinese tradition of carving at a tiny scale and are closely related to small purely decorative sculptures called okimono.

This closeup of a tattoo carved on the back of a figure on a netsuke shows the intricate detail on these tiny sculptures. Los Angeles County Art Museum.

Netsuke were popular in the Edo period (1615-1868). Worn by wealthy men such as merchants, various styles of netsuke could be swapped out depending on the wearers’ preference or the season of the year. They demonstrated the wearers’ cultural sensibilities.

There are netsuke that portray almost every possible aspect of Japanese culture.

Many netsuke depict everyday objects, such as this one of ceramic dishes. Almost every kind of day use item was depicted in netsuke. Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

This netsuke depicts a flying mythical figure from Japanese and Chinese folklore and religion. Such figures along with famous historical personalities were common subjects for netsuke. Los Angeles County Art Museum.

Animals were other subjects for netsuke carvings, such as the birds (Los Angeles County Art Museum) and the elaborate cat (Asian Art Museum, San Francisco) below.

Fishermen catching fish, woodcutters cutting wood, animals, flowers, abstract designs, tools, roof tiles and coins were carved into netsuke. Some netsuke use Christian symbols such as Christ on the cross.

This is a particularly elaborate version of a sagemono ensemble. Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

Before it was illegal to harvest elephant ivory, it was the most common material used for netsuke. Netsuke were among a myriad of products that contributed to the elephant’s worldwide decline in numbers. Hippopotamus teeth, boar tusks, rhinoceros horns, walrus tusks, whale bones and sperm whale, bear, boar and tiger teeth are other materials that have been used for netsuke. The casque, or helmet-like hard structure on the head of the helmeted hornbill was another material carved into netsuke. Predictably, a number of these animals are endangered, some critically so, partly because of harvesting for decorative items.

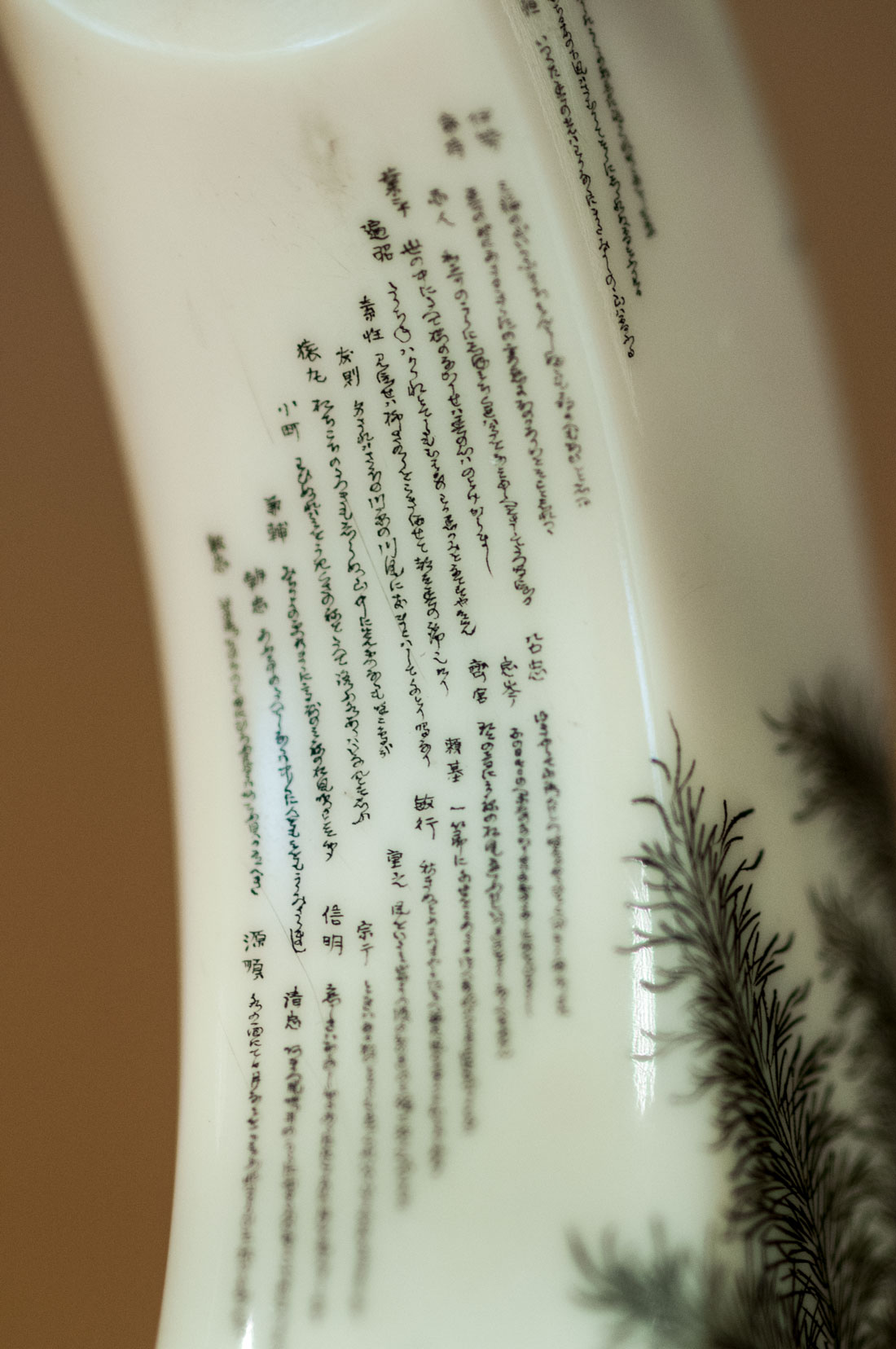

A tooth carved into a netsuke. Below, the miniscule Japanese characters on it are visible. Los Angeles County Art Museum.

Another material used for netsuke has been black coral, which also is used in jewelry making. It is declining because of harvesting, ocean acidification, invasive species and climate change and it has become illegal to move it across international borders. However, there is a large illegal market for it.

Netsuke also were made of boxwood and other hard woods, clay or porcelain and laquer, woven cane and bamboo. A partially fossilized wood called umoregi that formed from buried and carbonized cedar and pine trees also was carved for netsuke.

Some netsuke were carved from shells, often with entire scenes inside. Los Angeles County Art Museum.

Some of the most interesting netsuke were created from nuts. The ivory-like tagua nut from the ivory palm is easy to carve when wet. To carve walnuts, a hole first would be drilled in the walnut and a small worm inserted that would eat out the meat inside. Then the walnut would be carved as a netsuke. The walnut is polished and finished with shellack.

Metal was sometimes used, but often only as an accent on netsuke carved from other materials. Stone such as agate also was used. Some netsuke are inlayed with coral, ivory, mother of pearl, horn and precious metals. For some time during the Edo period, no one lower than the social class of samurai was allowed to wear jewelry, and netsuke took the place of jewelry in the clothing of merchants.

A netsuke inlaid with gems. Los Angeles County Art Museum.

Some of the most interesting netsuke have moving parts or house hidden figurines.

Netsuke started to disappear from Japanese men’s clothing after 1868 in the Meiji restoration, when it became common for Japanese to wear western dress. Westerners who visited or lived in Japan during the same period became obsessed with both netsuke and inro boxes. Their collecting kept up demand for netsuke and spread them all over the world. Some of the greatest netsuke collections today are outside Japan, as they were exported in large quantities in the 19th century. Some art dealers specialize in netsuke and their accompanying boxes or pouches, and Christie’s auction house has regular Japanese art auctions that include netsuke.

Netsuke still are made today for collectors. They are sometimes made of mammoth ivory, which is harvested in large quantities from Siberia and elsewhere. Ivory dust or ivorine also is mixed with clear resin and carved like ivory. It sometimes is artificially aged to give it an antique appearance on netsukes that are passed off as antiques.

A single netsuke can take up to two months for a master carver to create, using a variety of fine blades and working with the grain of the carving material. These netsuke command high prices and are sought after by collectors, with more affordable ones made by master carvers’ students. Many netsuke carvers today are not Japanese. They live all over the world. The most important factors in a netsuke’s value is the carving quality, rarity and originality and artistic quality.

This year’s convention of the International Netsuke Society is in Amsterdam, Netherlands, in September and October. This organization has local chapters in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, Chicago, Washington DC, New York, Europe, Tokyo, Melbourne, Australia, Moscow and the Ukraine.

A number of museums have beautiful netsuke collections donated or loaned by private collectors. The Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, California; the Los Angeles County Art Collection; the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston; the British Museum and Victoria and Albert Museum in London all have netsuke collections. The Kyoto Seishu Netsuke Art Museum in Kyoto, Japan, has more than 5,000 netsuke, 400 of which are on display at a time. The Tokyo National Museum in Tokyo, Japan, also has a netsuke room. Other museums have small displays.

So what did Japanese women of the Edo period do with their small portable items? They tucked them in their sleeves.

A netsuke depicting a Japanese woman. Los Angeles County Art Museum.

Check out these related items

A Palace to Remember

Visible traces of the Heijō Palace, Japan's palace from which the emperor ruled in splendor, were gone, until the site was restored.

Battle of the Samurai

Osaka Castle marks the site of an epic samurai battle and one of the most important turning points in Japanese history.

Elements of a Japanese Garden

Imagine you're sitting in Los Angeles traffic on a hot day. Take a break and head for a cool green oasis - Suihoen Japanese Garden

Giant Buddha, Giant Hall

An emperor built a giant Buddha to unify his struggling country, as the center of a network of Buddhist temples throughout Japan.

Japanese Design Past and Present

Architect Kengo Kuma's village at the Portland Japanese Garden blends modern architecture with traditional Japanese design.

Katsura Villa’s Enigmatic Design

Modernist architects admired Katsura Villa as the pinnacle of Japanese architecture and design. It is more complex than they thought.