The Troubling Legacy of North America’s Oldest Brick House

Photos by Forrest Anderson

Not long after North America’s first permanent English settlement in Jamestown, Virginia, was established, an English planter named Arthur Allen built a large brick house across the James River.

Now North America’s oldest brick house, the 1665 building has become a microcosm of central themes that the United States still grapples with today – the meaning of democracy, race relations involving Native Americans and African Americans, women’s rights, and a persistent gap between rich and poor.

Historians have long debated the meaning and significance of the house, built when English settlers were just gaining a toehold in the Americas and determining what the society that became the United States would be like.

The house, now called Bacon’s Castle, has been the subject of numerous books, master’s theses, archaeological digs and other explorations that have sought to throw light on these issues.

The house rose across the James River from the founding community of Jamestown, Virginia, which had been settled just sixty years earlier. The English colonies were still in their infancy, young, raw and sustained by the growing of tobacco on English land grants.

English settlers were not entirely welcome as they pushed away from the coast onto Native American lands. The English struck up a thriving trade in deer skins, furs, and other commodities with Native American tribes. However, tobacco growing depended on abundant fertile land, and the settlers looked with greedy eyes on the lands on which Native Americans lived.

Native Americans and Bacon’s Rebellion

The first war between the colonists and native peoples broke out just two years after the settlement of Jamestown. The leader of the Algonquian-speaking Indians of Virginia, Powhatan, besieged Jamestown until reinforcements arrived from England. Using terror tactics also used in Queen Elizabeth’s conquest of Ireland, the English soldiers burned native villages and towns and massacred women and children. They captured Powhatan’s daughter Pocahontas in 1613, using her as leverage to make peace.

Two other wars, from 1622-26, and 1644-46, resulted in a defined border between English and Indian lands.

It was an uneasy peace, however, as English settlers continued to encroach on native lands. Chief Wahanganoche of the Patawomeck tried to work with the colonists, deeding them tribal lands. However, colonists who wanted more land falsely accused Wahanganoche of murder in 1662. The colonial House of Burgesses found the chief innocent, but colonists murdered him while he was returning home. The colonial government then demanded that all Patawomeck “sell” their land. In 1666, they declared war on the Patawomeck, calling for their "extirpation." The tribes of the Northern Neck of Virginia were essentially wiped out. In the process, the English enslaved many of their members and enacted policies aimed at breaking down tribal laws and native customs.

This set the stage for the 1676 conflict called Bacon’s Rebellion.

In the decade before the rebellion, English planter Arthur Allen had settled on an English land grant and built the 9,000-square-foot brick manor house that became known as Bacon’s Castle. He increased his land holdings and built a southern plantation that made him an influential planter and member of the emerging southern gentry.

Virginia planters were greedy for land on which to raise tobacco and other crops that they could ship to England and other ports, for labor to work their lands, and for political power in the emerging colony’s government.

They were ruled by British colonial governor and planter Sir William Berkeley, a veteran of the earlier Indian wars who was tasked by the British crown with keeping peace in the colony. Berkeley had surrounded himself with other elite planters upon whose loyalty he depended to rule the colony. Allen was among them, rewarded for his loyalty with a county justice of the peace position.

In 1675-6, in retaliation for a brutal English attack on a village in Maryland, Native American groups raided frontier English settlements.

A newcomer to the colony and cousin of Berkeley’s wife, Nathaniel Bacon, took several Appomattox natives prisoner in 1675, for which Berkeley reprimanded him. Berkeley’s goal was to maintain the tributary system with Native Americans that had been established as a buffer between the English colony and the tribes. He feared that attacking friendly Native Americans could lead to a war with “all the Indians against us.”

Bacon, on the other hand, saw all Indians as the colonists’ enemies. After Berkeley denied Bacon a commission to lead soldiers, Bacon led an unauthorized expedition against the friendly Occaneechees. They marched to a fort held by the Occaneechees and convinced them to capture warriors from an unfriendly tribe. The Occaneechees returned with captives who Bacon’s men killed. They then opened fire on their Occaneechee allies.

Berkeley charged Bacon with treason and had him arrested, but then pardoned him.

Bacon returned to Jamestown that month with 500 men, and forced Berkeley to give him a military commission. Bacon and 1,000-1,200 colonists then prepared for a campaign against the Native Americans.

After Berkeley captured two of Bacon’s men who Bacon had sent to capture Berkeley, Bacon again returned to Jamestown and besieged it. Berkeley and his men were forced to retreat to the Eastern Shore of Virginia, and Bacon entered Jamestown and burned it to the ground in September 1676. He also burned Berkeley’s plantation. The next month, Bacon died of dysentery.

His followers established small outposts throughout the colony, including occupying Allen’s house and making it the site of a rebel garrison. It was this incident that gave the house the name Bacon’s Castle, although Bacon never visited the house. Berkeley launched a naval campaign against the outposts, and ended up quelling the rebellion by January 1677.

Royal commissioners arrived with troops soon after to investigate the rebellion, and while they hanged eight of the total 23 rebels who were executed because of the rebellion, they also criticized Berkeley harshly for failing to prevent the rebellion.

The commissioners faced an avalanche of discontent over local taxes. They didn’t get on with Berkeley, who they accused of being too harsh on the rebels and trying them under military law after the rebellion was over. When the commissioners went to say goodbye to Berkeley and found that their coachman was the local hangman, they chose to walk to the landing on the James River instead of riding in the coach.

Berkeley was removed from office. He went to London in an attempt to clear his name, but died before he was able to present his case to the government.

The rebellion had several far-reaching and troubling consequences that still influence American politics and culture today.

It strengthened policies to deprive Native Americans of their lands and culture, and the older slaveholding gentry in Virginia – families such as the Washingtons, Lees, Carters, and Randolphs whose influence spread nationally and has reverberated throughout the South through the American Revolution, Civil War and into today's culture wars.

African American history

Bacon’s Rebellion is believed to have been a turning point in the history of African American slavery in the United States because after the rebellion, the colonial elite became fearful about slaves and indentured servants joining in a revolt. They began to move toward race-based slavery, passing laws that declared as enslaved anyone whose mother was a slave. They also curtailed the number of indentured servants, because former indentured servants were considered a source of discontent. As a result, the colony began to expanded its labor force of enslaved Africans.

The first recorded enslaved Africans in the United States had entered Jamestown in 1619, although there were Africans in North America before that.

In early Virginia, poor people of English and African background worked together in some ways. Slaves could become free and people weren’t confined in a single niche because the society was still developing, and there was a small population and vast opportunity. There was a range of status between being enslaved and free. Many indentured servants with long indenture periods died before being freed. Others ran away.

The African slave trade was intertwined with Virginia’s larger trade in the three-part voyage that began in Europe. Ships carried European iron, cloth, brandy, and firearms to Africa’s slave coast and exchanged them for enslaved Africans. The ships then set sale for the Americas, where they exchanged the enslaved people for sugar, tobacco, or other American products and then returned to Europe with those products.

At Bacon’s Castle, the first record of enslaved Africans dates from 1673, when Arthur Allen’s son, Arthur Allen II, brought six enslaved men named Simon, Emmanuel, Tony, Stephen, Mingo and Mathew to work on the plantation around the house.

Mingo later gained his freedom, married a woman named Charity and had a daughter named Jane Mingo. The Mingo family grew in Virginia into the 1830s.

The number of enslaved people at Bacon’s Castle grew until the Allen family owned about 100. Many were separated from their family members when they were sold in slave sales. Among them were a couple named Peter and Bess and their children, Rose, Peter, and Sue. Many others were born into and died in slavery at Bacon’s Castle.

Some of them were involved in the famous Nate Turner Rebellion in 1831, in which 200 Black people were killed. In the aftermath of the rebellion, 56 enslaved people were executed and more than 200 beaten. Virginia and other slaveholding states passed legislation further restricting the activities of both enslaved and freed Blacks. The laws further widened the chasm between enslaved Blacks and Whites, making it unlawful to teach Blacks to read or write and hold religious meetings without a licensed white minister. It became a criminal offence to possess abolitionist publications. Slaveholders promoted ideas justifying slavery, such as that it was necessary to civilize Black people.

An enslaved man from Bacon’s Castle named John Claiborne was convicted of participating in the Nate Turner rebellion and sentenced to be sold South in 1831.

The number of enslaved persons on the plantation grew to 300 at the beginning of the Civil War.

During the Civil War, several runaway slaves from Bacon’s Castle took up arms against white slaveholders in Surry County. In December 1864, a band of armed enslaved people liberated other enslaved people at Bacon’s Castle. Among them was a man named Collier who had been enslaved at Bacon’s Castle. Records indicated that among those freed were a man named Gilly and his grandchild.

After the Civil War, those who had been freed created families. In recent years, some of their descendants have returned to Bacon’s Castle to commemorate their ancestors.

The slave quarters at Bacon’s Castle were built in the 1830s, and one of the dwellings survived because it was used as a tenant house into the 20th century. Descendants of people who lived at Bacon’s Castle,of both races have held reunions at the site and Descendants Days have been held there.

Among activities at the slave dwelling was a 2012 overnight stay in it organized by the Slave Dwelling Project, an educational initiative to teach people about the history of slavery.

“I thought I would feel anger, but I feel nothing but my grandmother’s love as if she’s right here with us. I can’t begin to tell you what an amazing experience this is for us! It’s very healing. I’ve drove past this plantation the last 30 years and wanted no part of it. But The Slave Dwelling Project seemed different. It told OUR story,” a descendant of people who were enslaved at Bacon’s Castle was quoted as saying.

The participants in the overnight stay were awakened before dawn by one of them singing the Muslim call to prayer in honor of enslaved African Muslims who were forcibly converted to Christianity as a way of stripping them of their identities.

Family members descended from the enslaved of Bacon’s Castle also shared oral stories of their ancestors and participated in other cultural and spiritual activities.

The slave dwelling and the plantation’s smokehouse have been restored, and archeological excavations have been conducted around them.

The Civil War

The Allen family owned Bacon’s Castle until the 1840s. At the time of the Civil War, it was owned by the prominent Hankins family. Confederate Private Sidney Lanier was stationed at nearby Burwell's Bay for about a year and a half during the war with the Confederate signal corps. Lanier, who later became one of the South’s great poets, wrote poetry describing the beauty of nights at Burwell's Bay. He and his brother Clifford were friends of the Hankins family, and often visited the estate. Lanier proposed to Virginia “Ginna” Hankins in May 1867, but she rejected the offer because of an obligation she felt towards her motherless younger brothers and sisters. She and Lanier remained lifelong friends.

Ginna's brother, James DeWitt Hankins, was a law student at the University of Virginia when the Civil War began. He served as a Confederate artillery officer throughout the war. In 1866, he was killed in a duel that originated from a quarrel between him and a man named William Underwood while they were drinking in a tavern. The families of both parties were prominent, and the death set off a feud between them. Underwood pleaded not guilty at his murder trial on May 16, 1867, and the jury unanimously acquitted him. Lanier wrote a poem in memory of the dead Hankins.

Bacon's Castle was firmly in Confederate territory during the Civil War, and its owners supported the Confederate cause. The local church cemetery holds carefully tended Confederate graves.

Like many large Southern plantations that depended for their wealth on enslaved people, Bacon’s Castle fell into serious financial difficulties when slavery ended after the Civil War. Ginna's father, John Hankins, mortgaged the property before his death in 1870. She was unable to pay the mortgage and sold the estate two years later to pay the debt and provide for her siblings’ education. The Hankins family moved to Richmond where she became a teacher.

William Allen Warren bought the estate in 1880 and the Warren family kept it until 1973, when the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities acquired the house.

The association, now called Preservation Virginia, restored Bacon’s Castle. It is now a house museum with 40 acres and outbuildings including barns and the slave dwelling and a restored 17th century formal English garden. The Virginia Outdoors Foundation has a conservation easement on 1,260 acres of privately owned farmland surrounding Bacon’s Castle that ensures that it will be permanently protected from residential and commercial development.

The house is one of the most important historic buildings in the United States because of its more than three centuries of history.

Allen modeled Bacon's Castle, a rare example of American Jacobean architecture and the only surviving "high-style" house from the 17th century in North America, on mansions he had seen in England. It is one of three surviving Jacobean great houses west of the Atlantic, with the other two being in Barbados. The house has triple-stacked chimneys, Flemish gables, and carved compass roses decorating some of the cross beams in the rooms. Seventy-five percent of the brick on the building is original, and the fingerprints of those who built it can be seen in the bricks.

Both Bacon’s Castle and the remains of a 1754 brick church nearby have a reputation for being haunted. Many local people have claimed to have seen a ball of fire rising from the cemetery and drifting toward Bacon’s Castle. One former owner of the house claimed he saw a ball of fire and ran outside, fearing his barn was ablaze. Another person who slept at the house claimed to have woken up to see the ball circling his bed and flying out the window. Everyone at a church meeting at the cemetery once insisted they had seen the fire ball.

People have said they have heard knocking sounds, screams, laughter, footsteps, gunshots, doors mysteriously opening. People say they have been touched on the shoulder by an unseen being, and ghost sightings have been reported.

Some have said that the ghost of a young enslaved girl has touched them beseechingly in the cellar kitchen. Others say that they have seen the ghost of a young women who was sneaking out to meet her lover when her dress caught on fire and she died. Some have connected this tale to an enigmatic message etched on a window pane in the house.

Southern Culture

Arthur Allen II, probably the wealthiest planter in Surry County, Virginia, owned 10,000 acres. He supported Berkeley,and was removed from his Surry County Court position when Berkeley was deposed. When the governor’s successor died, Allen was reappointed to the court. He was in and out of office depending on the political winds in both Virginia and London.

The Allens were an early example of the larger English planter culture and lifestyle that came to define Southern culture and created a hierarchical society with a huge social and economic gap between the privileged elite and the enslaved people whose labor enabled the planter lifestyle.

The Allens, like other elite planters, used luxury imported objects and had elaborate social rituals to signify that they were gentry. The Allens renovated Bacon’s Castle in post-Renaissance English style and aligned their buildings in a symmetrical classical pattern common on 18th century Virginia plantations. The plantations were built to resemble aristocratic English estates.

The house and plantation’s history are an illuminating look at the life of women which helped formulate cultural expectations for American women.

Southern society held high expectations for the wives of planters. Allen II’s wife, Elizabeth Allen, was responsible for overseeing her enslaved servants, the huge house, work done in the domestic outbuildings, caring for her children, and supervising their education. A huge portion of her responsibilities was the supervising of raw foods produced on the plantation. That meant grains, a huge vegetable garden, a dairy operation, and the processing of meat from cattle, sheep, and poultry.

Plantations were like villages, with kitchens, dairy houses, barns, stables, storehouses, slave quarters.

Black enslaved persons worked behind the house or in the cellar to produce food. The cellar had a large fireplace used for cooking, and also was where the laundry was done. Enslaved women worked there from sunup to sundown stooped over the hearth to prepare and serve large, elaborate meals constantly.

Mrs. Allen was known for entertaining guests elegantly and keeping her house neat and in good order, but also was taken to court for misuse of a servant named Patt Biddy who was freed as a result. In her will, Mrs. Allen provided for the sale of her slaves, although not those that belonged to her husband’s estates. One of the greatest cruelties of slavery and greatest fears of enslaved persons was being sold away from family members when their owners died.

Women on the plantation turned milk into butter and cheese, milled grain, and made clothes from linen, flax, and wool. Under Elizabeth’s supervision. They made preserves, tarts and pies with fruit from the orchard and garden, and cultivated bees for honey.

Among the elaborate rituals on a plantation was that of tea drinking, which gave the Allens and other elite families a chance to demonstrate genteel behavior with special tea tables and other furniture, fine ceramic dishes, silver, pewter, and utensils.

Enslaved people were listed on inventories in connection with the rooms in the house where they worked.

If a planter’s wife ran her household well, she was considered an important asset to her husband and a sign of his gentility. She was expected to create a home he was proud of and to help “gentle” or keep him from being dissipated. Despite their supervisory role, white women were expected to act like they were delicate and shy. From this system arose American cultural expectations for women. Their husbands had legal control over their wives, who were defined as the daughter or wife of a man throughout their lives.

Check out these related items

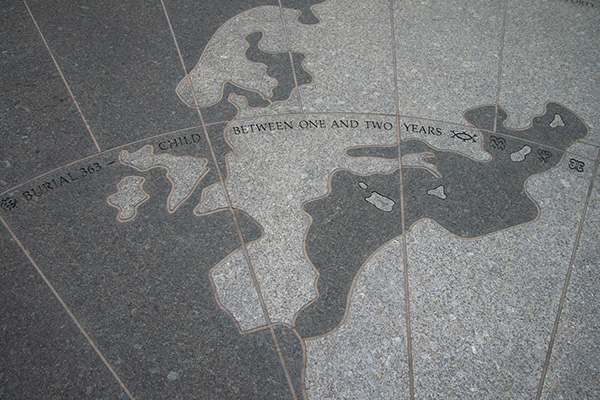

Memorial to Once-Forgotten People

A moving monument and burial ground in Manhattan comemorates enslaved people who once made up more than a third of New York City.

Nations Within a Nation

The first Native American to become U.S. interior secretary must deal with a fraught history of government-Native American relations.

Wolf in Ship’s Clothing

The picturesque town of Bristol, Rhode Island, once was a slave port and home of the nation's leading slave traders, the DeWolfs.

The Chesapeake’s Shrinking Isle

Smith Island in the Chesapeake Bay is rich in history but shrinking in land and population.

Why is Washington, D.C. so Roman?

The U.S. capital has more Roman-style architecture than almost any major city. We explore why.

The History of Race in America

The racial history of the United States belongs to us all, with the responsibility to resolve the accompanying outstanding problems.