The Panthéon of Paris

Photos by Forrest Anderson

Talk about identity issues. The Panthéon in Paris had them before it ever was completed. Constructed in the turbulent years before and during the French Revolution, the building has whiplashed back and forth from being a symbol of the French monarchy and Catholic church to a secular representation of democracy and equality.

Combine its turbulent politics with its classical Roman exterior and Gothic interior, and you’ve got an unsettling hybrid that manages to incorporate the conflicting themes inherent in French history.

Today, the building has embraced all of these themes – France’s ancient past as the Roman province of Gaul, its Gothic heritage of Christian kings, and its revolutionary history of democracy, liberty and equality. As the national mausoleum for the country’s super achievers in literature, art, science, philosophy, and statesmenship, the building celebrates human achievement while still functioning as a working Catholic church.

The word Pantheon comes from “pan” or all, and “theon,” or gods. France borrowed the concept from the ancient Pantheon in Rome, which originally was a temple to Olympian gods and had its own whiplash experience of being converted to a Christian church in 609. Because of the conversion, the Rome building survived while most other Roman monumental buildings crumbled away. As a result, the Pantheon in Rome became highly influential in buildings all over the Western world, where its combination of portico and round dome can be seen in government halls, library buildings and churches. The most prominent example in the United States is Thomas Jefferson’s library at the University of Virginia. These buildings, like the Roman Pantheon and its later namesake in Paris, are designed so that visitors pass through a series of marble columns to emerge into an enormous circular room.

The site where the Paris Panthéon is located was itself once the forum of the ancient Roman town of Lutetia. It later became the original burial site of Saint Genevieve, who led the resistance to the Huns when they threatened Paris in 451. In 508, Clovis, king of the Franks, constructed a church at the site where he and his wife were later buried in 511 and 545. This church later was dedicated to Genevieve. The abbey there was a center of religious scholarship during the Middle Ages. Genevieve’s relics were in the church and were used in solemn processions to pray for protection when the city of Paris was threatened.

French King Louis XV began the construction of a new church on the site in gratitude for his recovery from a dire illness in 1744. The church’s architect Jacque-Germain Soufflot had studied classical architecture in Rome. Known for blending styles, Soufflot created a building whose primary influence on the outside was the Pantheon in Rome. Inside, he created a Gothic cathedral that drew on France’s rich heritage of Gothic architecture. The church, which was influenced by the work of Italian Renaissance architect and painter Donato Bramante, was in the form of an Greek Cross with four naves of equal length as the arms of the cross and a monumental dome in the center. The classical portico has Corinthian columns.

The foundations were laid in 1758, The French Revolution of 1789 intervened before the building was finished, and the monarchy ended with the infamous execution of King Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette. This ushered in an extreme secular era when churches were sacked, confiscated by the new government, and closed.

Entering the building is unsettling because it looks like a Roman classical structure on the outside, but within are Gothic arches and frescos. The building was one of the first examples of neoclassical architecture in Paris and the highest structure until the Eiffel Tower and Arc d’Triomphe.

During the French Revolution of 1789, many churches were sacked of their religious ornamentation and closed. The Pantheon originally had religious figures, friezes and religious ornaments such as bells and lanterns, but these were replaced with secular ones. In 1791, the church was converted into a mausoleum dedicated to great French citizens, including heroes of the Revolution. Voltaire’s ashes were placed in the Panthéon in an elaborate ceremony in 1791, followed by the remains of several martyred revolutionaries and those of philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Two of the martyrs, the Comte of Mirabeau and Jean-Paul Marat, eventually were declared enemies of the Revolution as the politics changed, and their remains were removed from the mausoleum.

The upper windows were frosted over while the lower ones were bricked up to make the building darker and more like a mausoleum inside.

Napoleon Bonaparte rose to power in 1801 and restored former church properties, including the Panthéon, to the Catholic Church. Celebrations of events such as Napoleon’s victory at the Battle of Austerlitz, were held at the Pantheon. New artwork depicted both secular and religious aspects of the church, with Saint Genevieve being conducted to heaven in the presence of French rulers from Clovis I and Charlemagne to Napoleon and the Empress Josephine.

During Napoleon’s reign, the remains of forty-one illustrious Frenchmen were placed in the crypt - mostly military officers and high officials.

When the monarchy was restored to power, the building was a church and a few relics of Saint Genevieve were returned to it. New works were created for the dome to represent Justice, Death, the Nation and Fame. The fresco on the inner dome was updated to replace Napoleon with Louis XVII, Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, who were posthumously rehabilitated after having been beheaded during the Revolution. The crypt was closed to visitors. The main pediment now had a cross.

Enter the French Revolution of 1830. King Louis Philippe I who was placed on the throne was sympathetic toward revolutionary values, so the church was again converted into the Pantheon. The main pediment was redone with a patriotic theme of liberty and great men. After Louis Philippe was overthrown in 1848 and the Second French Republic rose to power, it designated the Panthéon “The Temple of Humanity.” Plans were made to create sixty new murals honoring human progress in different fields.

Louis Napoleon, elected president of France in 1848, staged a coup-d’état and declared himself emperor in 1852. The Pantheon again was returned to the church and given the title National Basilica. More relics of Saint Genevieve returned to the church and sculptures commemorating her life were added.

In the 1870 Franco-Prussian War, the building was damaged by German shells, and further damaged during fighting between the soldiers of the Paris Commune and the French Army. It continued to function as a church, but its walls were mostly bare until it was redecorated with new murals and sculptures that linked French national history with the history of the church. The murals have titles such as Christ Showing the Angel of France the Destiny of Her People.

In 1881, the church was transformed into a national mausoleum again and author Victor Hugo’s remains were placed in the crypt. Other literary figures and leaders of the French socialist movement were added through the 1920s. The Third Republic government decided that the building should be decorated with sculpture representing “the golden ages and great men of France,” and works were added commemorating the French Revolution, early French revolutionary leader Honoré Gabriel Riqueti and the count of Mirabeau. Historians have never agreed on whether he was a great leader or a traitor.

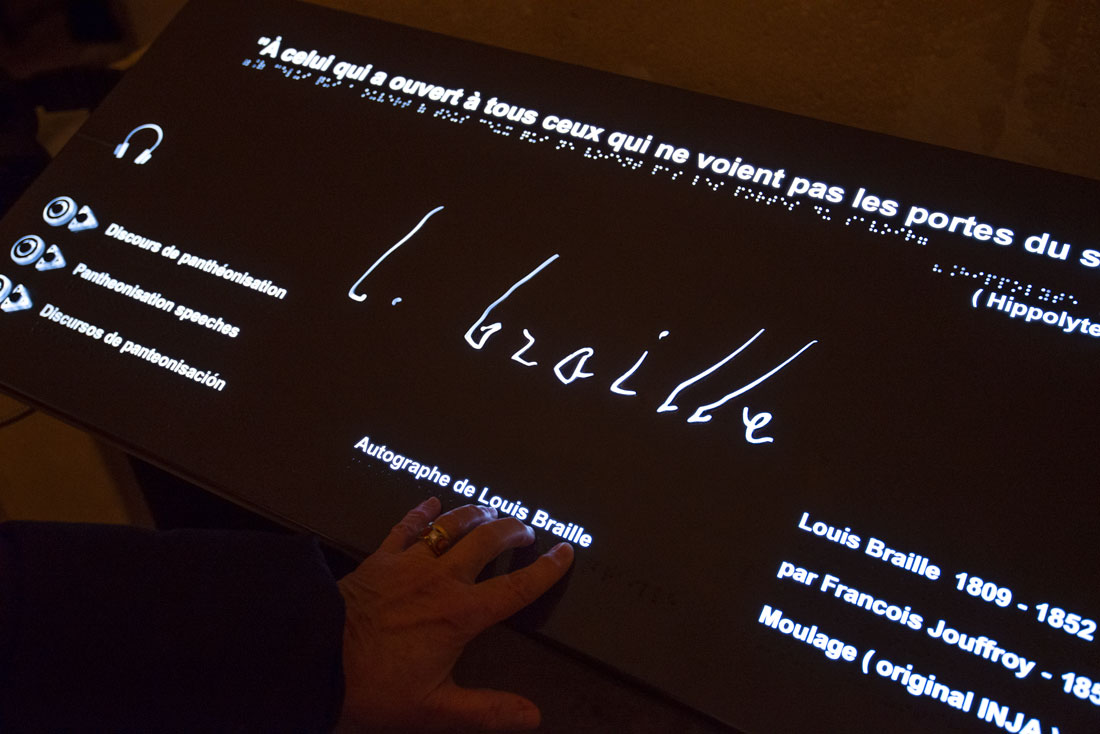

During the ten-year Fourth Republic after World War II, two physicists, abolitionist Victor Schœlcher; and Louis Braille, inventor of the Braille writing system, were among those added.

Resistance leader Jean Moulin; Nobel Peace Prize winner René Cassin who drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; Jean Monnet who was prominent in the creation of the ECSC, the forerunner of the European Union; Nobel laureates physicists and chemists Marie Curie and Pierre Curie and others were interred in the crypt. It has a permanent exhibition that provides details about the lives and work of those who were buried there.

The building has made peace with the varying political forces that made up France’s history and elements of them are commemorated together in the building. It functions as both a national mausoleum and a working Catholic Church where mass is held on the weekends.

The main features of the building are its classical façade, dome, naves with famous murals and crypt where prominent people are buried.

The Facade

The classical façade is modeled after a Greek temple. It features Corinthian columns, sculptures and figures of distinguished scientists, philosophers and statesmen – Rousseau, Voltaire, Lafayette, Napoleon Bonaparte, soldiers from each military service and students from the École Polytechnique. The pediment sculpture, which replaced an earlier religious one, represents the nation distributing crowns to great men that were handed to her by Liberty. The figures on the left are civilian heroes and on the right is Napoleon Bonaparte with soldiers from each military services and students in uniform from the École Bonaparte.

Inscribed on the façade is the motto “To the Great Men, from a grateful nation.” This Revolutionary motto was removed when the monarchy was restored, but brought back in 1830.

The Dome

The building’s 272-feet-high dome was designed to rival those of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome and St. Paul's Cathedral in London. It is constructed of three domes within each other. The painted ceiling on the second dome is visible from below through an opening in the first dome.

The outermost dome, visible from the outside, is built of stone bound together with iron cramps and covered with lead sheathing. Critics of the building’s architectural plan insisted that the pillars couldn’t support such a large dome, so Soufflot strengthened it with iron rods that were a precursor of modern reinforced buildings. By the 21st century, the bars had deteriorated and were replaced in a major restoration. Concealed buttresses in the walls also help support the dome.

Initially, a statue of Saint Genevieve was supposed to sit on the top of the dome, but a cross was placed on it in 1790 as a temporary measure. After the building became a secular mausoleum in 1791, a flag was placed on the dome between 1830 and 1856. The cross returned to the dome when Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte restored the building to a church, but a red flag was put in the cross’s place during the Paris Commune in 1871. After that, the cross was reinstalled.

The painting, the Apotheosis of Saint Genevieve, has a triangle in the center symbolizes the Trinity, surrounded by a halo of light, Hebrew characters spelling the name of God. Saint Genevieve can be seen in the painting. Groups of figures painted during the restoration of the monarchy after the French Revolution, represent French kings who protected the church - the first Christian king of France, Clovis; Charlemagne; Louis IX of France, or Saint Louis, with the Crown of Thorns that he brought back from the Holy Land to place in the church of Sainte-Chapelle; and King Louis XVIII and his niece. They are looking up into the clouds at Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, who were beheaded during the French Revolution. Angels are carrying the Chartre, the document by which Louis XVIII re-established the church after the French Revolution.

The four arches that support the dome are decorated with paintings from the same period depicting Glory, Death, The Nation and Justice (1821–37).

A replica of the 220-foot Foucault pendulum, a central feature of the building, hangs from the dome slowly swinging back and forth. The pendulum was designed by French physicist Léon Foucault in 1851 and hung from the dome to illustrate the earth’s rotation. It was removed because of complaints that it wasn’t an appropriate feature for a church, but a replica now hangs in the dome while the original pendulum is displayed at the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris.

Naves

The western nave has religious paintings depicting Saint Genevieve and Saint Denis, Paris’ patron saints. The southern and northern naves have murals of Christian heroes of France – Charlemagne, Clovis, King Louis IX and Joan of Arc.

The Crypt

The crypt houses the tombs of eminent French superachievers who played an important role in the history of the nation and provides information about them.

A spiral staircase leads down to the Panthéon’s crypt, in which are hallways, rooms and arches filled with stone tombs.

Rousseau, Victor Hugo, author of The Hunchback of Notre Dame and Les Miserables, scientists Pierre and Marie Curie, Louis Braille who created the Braille reading system for the blind, and author Alexandre Dumas are interred there. Some of the heroes’ remains were transported to the crypt from interment at other sites in ceremonies intended to correct political wrongs. For example, Dumas (1802-1870), who wrote The Three Musketeers and other famous novels, was originally buried elsewhere. His remains were transferred to the Pantheon in 2002, in an elaborate procession in which the coffin was draped in a blue velvet cloth inscribed with the Musketeers’ motto, “One for all, all for one.”

Seventy-three men and five women’s remains are in the Panthéon, a process called panthéonisation.

The crypt is the national mausoleum for French heroes. Interment is allowed only by a parliamentary act for "National Heroes".

Because of rumors that Voltaire’s body was stolen by religious fanatics in 1814 and thrown into a garbage heap, his coffin was reopened in 1897. His remains still were inside of it.

Former French President Jacques Chirac unveiled a plaque in the Panthéon in memory of more than 2,600 people who saved the lives of Jews who would have otherwise been deported to concentration camps. About ¾ of the country’s Jewish population survived the war, many of them because of people who helped protect them at the risk of their own lives.

Check out these related items

Paris’s Oldest Church Restored

Paris' oldest church, Saint Germain des Prés, is emerging from layers of grime and soot as a meticulous restoration reveals its vibrant color.

Resting Place of Kings

France's dazzling royal necropolis, the Basilica of Saint Denis, is also the birthplace of Gothic architecture.

The World Mourns Notre Dame

Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris, France's national cathedral, was badly damaged in a fire.

Marie Antoinette and Barbie

Since she was guillotined in the French Revolution, Marie Antoinette has become one of the most popular icons worldwide.

A Tale of Two Roman Cities

The amphitheaters, military garrisons, forums, trade and craft shops of two Roman colonial cities have emerged from the dust.

Britain and Greece’s Parthenon Dispute

What are the chances that two men from one family set off international disputes by carting off treasures from Greece and China?