Reinventing Civil War Reenactment

Photos by Forrest Anderson

The combination of the pandemic and the nose dive that the Confederacy has taken in public opinion in the past year have been tough on Civil War reenactments.

While some reenactments are back this year, others were canceled again – some permanently. Some communities are reinventing them to move away from battles and toward a broader, more diverse version of the war’s history.

Civil War reenactments and other events have declined in popularity during the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement. The National Park Service’s five major Civil War battlefield parks — Gettysburg, Antietam, Shiloh, Chickamauga/Chattanooga, and Vicksburg —had a combined 1.8 million visitors in 2020, down from about 3.1 million in 2018 and 10.2 million in 1970. Gettysburg’s visitor numbers were down 92 percent from 1970. This year, more than 6,000 people participated in the annual battle reenactment at Gettysburg compared to a 1998 high of an estimated 30,000 re-enactors and 50,000 spectators.

The largest Civil War reenactment in Florida, in Hernando County, was canceled permanently after the Boy Scout Council that owns the land opted out. Organizers cited the pandemic, declining profitability and interest in reenactment, and recent national racial unrest were factors.

The decline in reenactment has raised fundamental questions in communities across the nation about how American history should be portrayed in public settings, whether the Confederacy’s juggernaut on the historical narrative is finally breaking, and if so, what should replace that narrative.

With the removal of many Confederate monuments and symbols, is the Confederacy finally on the run? What does that mean for the way in which Americans reenact and interpret our history?

Reenacting hit a high in the 1990s and 2000s, at the same time that an interest in family history burgeoned with access to historical records on the Internet. Many people who found on-line records documenting their ancestors’ involvement in the Civil War became involved in reenactment and joined Confederate or Union reenactment units.

We lived in North Carolina in the 2000s, feeling at times as though we were embedded with the troops in the Civil War. One of the greatest culture shocks that Yankees and other outsiders experience when moving to the South is the war’s ongoing presence on monuments, in patriotic celebrations, at hoop-skirted weddings and at tourist sites and other public venues. At reenactments, both Civil War soldiers and civilians operate in a weird time warp that includes hardtack and battle tactics alongside ATM machines and mobile phones. Reenactments play with your mind.

My first experience with reenactments was encountering a group outside the state capitol in Raleigh, NC, the men marching around in gray uniforms and caps, and the women in bonnets and hoop skirts. I stopped to talk with one woman who proudly stated that she was a member of a Confederate unit and had renovated her family’s historic home with an antebellum parlor furnished with authentic antiques and reproduction Civil War-era upholstery fabric, curtains and carpets. On a hot sultry day, she pulled up her hoop skirt to show me her reproduction petticoat and bloomers, pushed her vintage glasses up on her nose and handed me a pamphlet advertising the Daughters of the Confederacy.

I was nonplussed by this apparent ghost from what I considered a distant past. I had an ancestor who had served on the Union side while his brother had fought for the Confederacy, but after the war they hitched up a mule train together and went West. No hard feelings. That was eons ago, a four-year trauma in America’s long history. I had no idea people were still carrying on with the war.

Oh ho, was I ever wrong. I casually asked if the Daughters accepted recruits among descendants of Yankee soldiers. My recruiter stopped her spiel, stammered, wiped her forehead nervously and finally said uncertainly, “Uh, I don’t know … I’ll ask…. “

She wandered off and didn’t come back.

Over our next 14 years in the South, this attitude changed as, stung by accusations of racism, the organizers of large Civil War reenactments began to bend over backwards to make sure battles had enough Union soldiers, with some Southern reenactors donning blue as needed to even out the numbers.

One organizer, who played Confederate General Robert E. Lee while his colleague galloped around on his horse in a General Ulysses S. Grant suit, told me that reenactments shied away from politics.

“We just present the history of a battle in a balanced way,” he said. This “don’t ask, don’t tell” approach to Civil War politics coincided with the general atmosphere of political correctness that prevailed in the 2000s.

Among boots on the ground, however, plenty of reenactors still insisted in lengthy debates that the war would have been won (for the Confederates) if Lee had done this or that or the weather had been different or Stonewall Jackson had shown up here or there. The implication was that it should have been won – missed opportunity.

I got into these discussions because I was getting a master’s degree in public history at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, which meant research at Civil War battlefields and historic plantations. Listening to these debates was surreal, because historians’ consensus is that the South never had the economic and political wherewithal to win the war and that the war’s central issue was slavery.

Occasionally, a Southern reenactor spouted myths such as that enslaved people lived better than white laborers in the North or that no one in North Carolina owned slaves and the state’s troops just fought for state’s rights. Most reenactors, however, showed little to no interest in the history of slavery.

So why reenact if you didn’t care about the war’s core issue? I asked one hoop-skirted Latina girl that, and she replied that her boyfriend was into reenacting and she liked the guy. Okay….

The girl and her boyfriend at a reenactment.

Many reenactors said they were military buffs, some because they were veterans and enjoyed the comradery of drilling and camping with other military enthusiasts.

Others are obsessed with the gear. Reenactors divide themselves into three categories based on their commitment to authentic gear.

Farbs are the bottom rung. They wear non-authentic clothes like jeans, tennis shoes, polyester clothes, zippers, and Velcro. The term Farb was coined during the 1976 Revolutionary War Bicentennial celebration as a perjorative term for inauthentic reenactors. It means Far Off Resembles British and has been adopted by Civil War reenactors as a term for casual warriors.

The next step up is mainstream reenactors who appear outwardly authentic, but wear modern underwear, eat modern food and use modern items like mobile phones at reenactments.

The highest level are hard cores, who during a reenactment live as much as possible like someone from the 1860s. They march around in boots with holes in them. They meticulously research and recreate their uniforms down to the underwear. They subsist on hard tack, salt pork and only seasonal and regional food during reenactments. They sometimes march for days to get to a re-enactment and stay in character throughout it. Some don’t even bother with modern audiences, preferring to take off cross country with other hard cores or camp out and play soldier on private land away from modern conveniences.

All of these soldiers need gear which it is up to them to pay for. Many reenactors have both northern and southern uniforms and switch sides as needed to even up the ranks. Some also reenact other wars. It’s an expensive hobby – a single reproduction Civil War rifle can cost more than $1,000. Some reenactors wear civilian costumes – gun runners, shop keepers, blacksmiths.

An entire industry of artisans shows up at reenactments and runs ecommerce websites to supply muslin shirts and period dresses, uniforms, caps, canteens, swords, boots, bedrolls, tin cups, guns, bayonets, rifles, flags – the list goes on.

A reenactor browses in a uniform shop at a reenactment.

Cavalry is particularly expensive - horse trailers belonging to the cavalry line up in parking lots next to battlefields. The artillery isn’t cheap either, as it requires functioning cannons. Many former reenactors cite the cost as a main reason why they deserted their units.

Another reason for declining numbers of reenactors is that the hobby is ageing out. Google the term “reenactments” and one of the top types of articles you will find is obituaries that list reenactments as among the deceased’s hobbies. Many reenactors are in their 60s and 70s. The gray beards and pot bellies prevalent in many reenactment units are a far cry from youthful photographs of actual Civil War soldiers. Reenactment units are dwindling because they are recruiting fewer younger members.

Especially in the South, this has a lot to do with the flag they fly. As the movement to remove Confederate flags and other Confederate symbols from public places has gained steam, many younger people are turning away from involvement in events at which the flag is raised. Some former reenactors say they have dropped out as American politics have polarized because the political atmosphere at reenactments has become tense and they feel threatened.

A recruitment table for Confederate reenactors in the early 2010s proudly displayed the Confederate flag. After the past five years of acrimonious political polarization, many moderates no longer want to attend events where it is displayed.

Some reenactors have been turned off as other reenactors have protested at events at which Confederate monuments and symbols are being removed and as neo-Nazis have connected their activities with the Confederacy.

Some Union reenactors say they resent the bad image that the Confederate flag has given to their own reenactment efforts to honor their Union ancestors who fought to preserve the Union and end slavery.

A traditional reenactment can include a parade, campfire dinners, a costume ball, markets where replica Civil War souvenirs and gear are sold, demonstrations of Civil War-era skills, battle reenactments and cannon shooting.

The choice of activities dates back to the war, when sham battles were staged in local communities as part of recruitment and training of local troops. They were often accompanied by community dances and parades.

In the 1880s and early 20th century, reunions of Civil War military units were popular and often included reenactments. Some were held on Civil War battlefields. These events often were part of larger community holiday celebrations where aging Civil War veterans in uniforms and medals were honored. As they died off in the 1950s, younger people began to don replica uniforms to keep the tradition going. Modern large-scale reenactments took off during the 1961 Civil War Centennial and the hobby grew, reaching a peak in the 1990s partly because Ken Burns’ documentary “Civil War” got 139 million viewers, James McPherson’s 1998 book, “The Battle Cry of Freedom,” spent months on the best-seller lists and films included reenactors as extras.

The Internet provided reenactment planners with easy communication with other reenactors and sophisticated maps upon which they could choreograph battles. People from all walks of life – state employees, fire fighters, professors, garbage collectors, police, medical personnel and more – took up reenacting.

The Internet, an ideal way to spread the word about reenactments, facilitated weekend gatherings of tens of thousands of reenactors.

At reenactments, doctors set up gory looking battlefield hospitals and pretend to amputate limbs while a bucket of bloody fake body parts sits nearby, veiled women in black wander around as widows, blacksmiths demonstrate their craft and photographers take black-and-white photos of people in period garb.

A post-battle mock surgery performance on a "wounded soldier" at a reenactment.

Homeschooling groups of women, children and teenagers demonstrate weaving, quilting, cooking and other Civil War-era home front activities.

Teenage girls in Civil War costumes writing letters to soldiers from the home front as part of a reenactment.

The reenactments became a godsend for local officials who were marketing the Civil War as a tourist draw, and hotels, restaurants and tourist offices providing package tours jumped on the bandwagon.

An incongruous but ubiquitous sight at reenactments are motorcyclists who roar into parking lots next to battlefields on gleaming Harleys and stride through the crowds sporting tattoos, muscles, decorated leather jackets and tough guy scowls. For the most part, their menacing appearance is a costume. “I’m a government clerk,” one told me mildly. “This is just a fun event to ride to on the weekend.”

Motorcyclists at a reenactment at a historical site in North Carolina.

Every reenactor has campfire stories to tell about roughing it at reenactments. I knew one who had to be hauled off to an emergency room for stitches after stabbing himself in the bum when he accidentally sat on his bayonet. Often the stories are muddled together in a hopeless tangle with historic tales.

“My family has seven generations of people who fought on the losing side in wars, and the Civil War was one of them,” said a cheery young man dressed as a Confederate Civil War chaplain who pulled out a large cigar and lit it. His next revelation was a bit of a stunner – he was working in real life toward becoming a U.S. Navy chaplain.

“Is that a good idea? Let's hope your family curse doesn’t hold,” I told him.

Many reenactors collect Civil War weapons, photos and macabre items such as lockets with a deceased relatives’ hair in them. Some reenactor units are based on original Civil War military units. They help families research their family histories which have ties to the units. Some units attend annual spring training encampments in musket safety, historically correct drills, camp etiquette and skirmishing. They then engage in reenactments between May and October. One criticism of this activity is that reenactment emphasizes the most interesting military units at the expense of telling ordinary soldiers’ stories.

Critics of Civil War reenactments also say that they minimize and romanticize the terror of war in general and the horrible legacy of the Civil War in particular by turning it into entertainment and wholesome family outings. They also say that reenactment lends legitimacy to the Confederacy that it never had and thus perpetuate current racial conflict.

Some Southerners resent the implication that the South equals the Confederacy to the exclusion of other key Southern historical and cultural currents – colonial history, the contribution of African American, Native American and Hispanic American culture to the region, the Southern contribution to World War II, and the history of civil rights as well as the South’s rich music, art and culinary traditions. Other criticisms are that some Civil War reenactments are key events in communities that never had an actual Civil War history.

Why does the Civil War hold such a central position? Part of the reason is that the South relies economically on the preservation of its Confederate past as tourists spend millions of dollars touring antebellum plantations and going on carriage rides through historic neighborhoods. Slavery persisted in the south for hundreds of years and many traces of it and segregation remain. Weddings and family reunions at plantations, servants’ entrances built into houses and mansions, two bathrooms for each gender at old train stations, and buildings named for Confederate generals are part of the landscape. Civil War trauma was intergenerational – many widows, children growing up without fathers to tell their children of their hardships, slaves freed and then pulled back into share cropping and segregation, lynchings, the Ku Klux Klan.

Many Southern cemeteries have separate white and black sections. Churches were segregated until the 1980s and some still are de facto. Neighborhoods are more segregated today than in the 1960s. Some people still live near or on land where their ancestors were slaves. I met white farmers who employed on their land the descendants of slaves who once worked the same fields. People own Civil War family heirlooms, including ones with dents where Union soldiers kicked them while raiding homes. A white neighbor of mine is descended from the same Confederate ancestor as a black high school classmate who had the same name as his. The two knew each other throughout high school, but never brought up the subject. Historic markers on highways commemorate the march of Sherman’s army through the South. Museums are full of Civil War military gear, most of it Confederate. These scars are all over the Southern landscape. Reenactments reflect the way some rural white Southerners see the United States and its politics, through the lens of fighting battles with a northern urbanized world.

One effect of tourism and American film and books is that the Civil War is popular internationally. American Civil War reenactment is popular in Canada, Great Britain, Germany, Australia, Italy, Denmark, Sweden and Poland. Some European units show up for American reenactments.

The biggest criticism of reenactments is that the emphasis on the military obscures the war’s key issue – slavery. The missing factor in the majority of Civil War reenactments is African Americans. In many communities during the Civil War, black and white populations were roughly equal, but Civil War reenactments are mostly white events.

There are a few African American reenactment groups that consider their mission to highlight African American groups who fought for freedom on the Union side. In addition to reenactment, they research the lives of black Civil War soldiers, most of whom were former slaves. Some have found their own ancestors among the nearly 200,000 African Americans who fought for the Union.

An African American reenactor in a unit that commemorates the more than 200,000 African American soldiers who fought for the Union.

Some reenactments are reinventing themselves amid such concerns and ones about the effect of battle reenactments in communities traumatized by gun violence that is at its highest national level in decades. Clivedon, PA., the site of a key Revolutionary War battle for control of Philadelphia, has high gun violence. It canceled its battle reenactment last year and revised its annual Revolutionary War festival as a tour through Historic Germantown with activities at 16 historic sites.

Reenacting is moving away from the traditional narrative that that emphasizes the preservation of the Union but downplays slavery, Reconstruction and the rolling back of black civil rights. More reenacting is confronting slavery as well as other social issues.

More African-American reenactors see slavery as the American Holocaust, and reenact purposely to initiate conversations to confront the evil of slavery. They say that despite the divisive potential of such reenactment, it actually has proven to be an avenue for people of various backgrounds to have positive conversations about race.

Michael Twitty, a culinary historian and food writer, stages reenactments called “Antebellum Chef,” in which he uses food-preparation methods based on the practices of enslaved cooks in the South. Through his dress, ingredients and tools, Twitty demonstrates what it was like for a slave in the kitchen of a plantation estate. Twitty says his job is to show what the life of an enslaved person looked like so that people can photograph it with their iPhone and share that knowledge.

Cheyney Knight has worked with more than 40 historical sites since starting her company, Not Your Mamma’s History. Her company helps museums, historical sites, historical societies and private businesses develop specialized programing about slavery and the African American experience in the 18th-19th century. She also trains staff from all backgrounds in how to talk to diverse audiences about slavery. She has presentations about slavery, one that depicts her as a hearth cook who prepares West African, African American, Dutch and British food and performance pieces that highlight how slavery continues to shape the nation’s politics.

There are presentations by African American reenactors about the Underground Railroad, the abolition movement and skills that enslaved African Americans had.

More historic plantations have added slave narratives and exhibits to their tours. Those that focus on the history of enslaved populations get more African American visitors than other historical plantations. There have been reenactments of enslaved Africans going through the Middle Passage, slave auctions, slave rebellions and lynchings that challenge dominant white versions of American history. African Americans have become more involved in preserving the history of slavery and holding family reunions and events at antebellum sites where people were enslaved.

An African American reenactor, New Bern, North Carolina.

Women in general have been marginalized in battle reenactments, but newer presentations show women struggling to maintain their farms while their husband, sons and brothers are off to war, women spies, and women who ran printing presses or other enterprises.

Some white reenactors have discovered in their research that their families owned and mistreated slaves and are using reenacting as a way to confront that past. They also are grappling with the historical reality that most people who fought in the war were poor, which flies in the face of romanticized myths, and that many became disillusioned and deserted from the Confederate army. Through this work, antebellum historical sites and battlefields are taking on new broader meanings.

Reenactor Nancy Whittle said that when she shares in schools information about whippings and other abuse that Harriet Tubman went through as a slave, young girls come up to her and share their stories of abuse they are experiencing at home.

Whittle has noted that when she sings songs that Harriet sang and that also were passed down in her own family from slave ancestors, she feels like she really is Harriet Tubman. Herein lies the great strength and weakness of reenactment – its ability to make people feel as though they actually are or are interacting with actual historical characters.

Reenacting is unlikely to disappear because it is a powerful way of processing collective loss and grief. In almost every society since ancient times, ritual reenactments of major events have been held. Pilgrimages, sacred and civic holidays, and much religious ritual is based on recreation of past historical events and legends. Civil War reenactments are public theater that process collective grief again and again by enabling reenactors and their audiences to feel it.

In battle reenactments, grief is limited mainly to dying in battle. Few cavalry die because they have to risk getting injured by falling out of the saddle. Soldiers who die too early miss out on most of the action. Some reenactors told me they just fell down when they got tired of running along carrying gear. After the battles, soldiers return to life, shake hands with those on the opposite side, and turn out to a period dress ball at which musicians play Civil War-era music that they also sell on CDs. Despite this, some reenactors are profoundly moved by reenacting battles on sites that Civil War soldiers fought and are buried at.

Death is awkward when military reenactors portray a specific person such as General Robert E. Lee or General Grant. These reenactors often give first person presentations which can be jarring when they report their own deaths and then open the floor up for audience questions. Robert E. Lee, a slave owner and the most well known leader of the Confederate cause, is awkward these days anyway as his statue has come down even in the once-Confederate capital, Richmond, Virginia.

A reenactor portraying Robert E. Lee at a reenactment of the South's surrrender, North Carolina, in the early 2010s.

Some reenactors try to confront death and loss in a deeper way by portraying through dramatic reenactments the effect on family members of a soldier's death and the pain enslaved people felt when their family members were sold. Reenactments often surprise both participants and audience by generating deep emotional reactions. Below, a son waits for his soldier father to come home in a reenactment performance.

Such genuine emotions in the face of the performance of reenactments are common and are called "touching the past." Reenactors at Gettysburg often report encountering ghost Confederate and Union soldiers for brief moments or seeing brief glimpses of real battlefield scenes. Many reenactors have powerful incidents in which they feel as though they actually are the characters they are playing, including some in which witnesses simultaneously say they saw a reenactor’s countenance and even an entire scene momentarily change to appear like the past. Others have vivid dreams of battles or the brutality of slavery.

Replica objects use for reenacting can hold deep meaning. One African American reenactor said that she and fellow reenactors who portray enslaved women gather to sew their costumes, ripping pieces from them to make rents and then exchanging the pieces and patching the rents. This symbolizes for them the rending of enslaved families as family members were sold.

In a one lynching reenactment, African American reenactors who donned Klansmen hoods said afterward that they were never do it again because of the irrational hatred they felt well up inside when they wore the hoods.

Objects associated with slavery reenactment such as shackles can have such a traumatic connotation that companies that produce them post disclaimers online that they are to be used only for theatrical performances and reenactments.

As American demographics continue to diversify, reenactment will continue to play a role in education, tourism and cultural perceptions of citizens. Despite fears that reenactments that confront slavery will fuel more political strife, reenactors who present on those topics have said that they actually tend to bring diverse audiences together and spark positive conversations about race. Taken together, they hope that such conversations eventually will produce a more inclusive and honest narrative about some of America's most divisive topics.

More photos of Civil War reenactments

Check out these related items

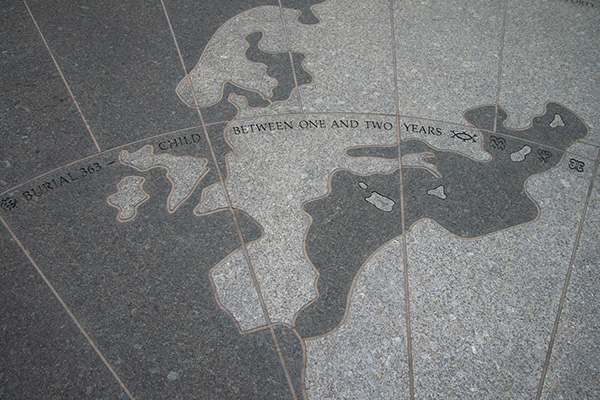

Memorial to Once-Forgotten People

A moving monument and burial ground in Manhattan comemorates enslaved people who once made up more than a third of New York City.

The History of Race in America

The racial history of the United States belongs to us all, with the responsibility to resolve the accompanying outstanding problems.

The Racism of Confederate Statues

The racist past associated with the Confederacy and Confederate monuments has a complex history.

Getting A Vaccine against Racism

A mother of non-white children compares her fears for her children because of COVID-19 and her fears for them because of racism.

New Orleans - Exuberant Hybrid

New Orleans's hybrid culture is the result of its 300 years as the gateway to trading networks of the Mississippi River.